This story is co-published with THE CITY.

Not long after he took over the police union he would lead for nearly two decades, Sgt. Ed Mullins sued the New York Police Department in a case that would eventually earn his members $20 million in back pay and damages from the city.

The lawsuit showed gumption, and the judgment, issued in 2012, endeared Mullins to the thousands of NYPD sergeants he represented. But the money wasn’t the half of it.

A ruling against the city, handed down partway through the case and hardly noticed at the time by anyone but the lawyers, may have turned out to be far more valuable to Mullins and his union, the Sergeants Benevolent Association.

In a written decision, the federal judge overseeing the case told the city to back off Mullins’ union, barring the Police Department from investigating claims of SBA members lying under oath that had arisen in the course of the litigation.

It was a message heard loud and clear, and one that would echo through City Hall and One Police Plaza for years to come.

As the lawsuit wound its way through the courts, city officials would learn of other allegations involving the SBA, some of them specifically related to Mullins. But oversight agencies begged off or, in the case of the city’s chief financial officer, did not act when claims of fraud came to light, according to a ProPublica review of city records and interviews with several people who worked in city government or law enforcement at the time.

In the years that followed, Mullins strengthened his grip on the 13,000-member SBA, repeatedly winning reelection with little opposition. And as a reckoning over race and the criminal justice system took hold over the last few years, Mullins used his perch atop the union to fashion himself as a pro-police provocateur.

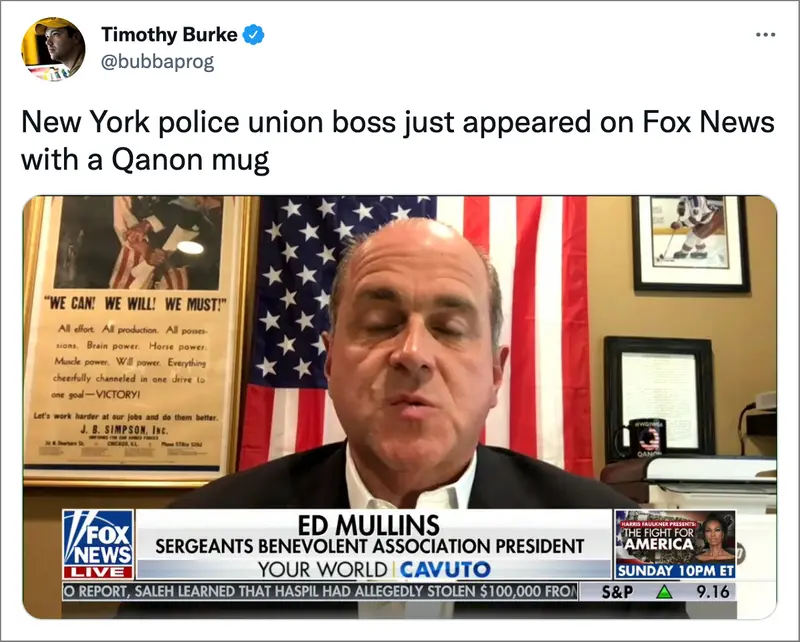

As activists and local lawmakers pushed for police reform, he took to Twitter, Fox News and podcasts to spread increasingly inflammatory commentary that went largely unaddressed by NYPD leaders.

The union that he led, which receives tens of millions of taxpayer dollars a year for its members’ health and welfare funds, carried on with a similar lack of scrutiny.

Until a couple of months ago.

On Oct. 5, federal agents executing search warrants raided Mullins’ home on Long Island and the SBA’s headquarters in Manhattan. The Daily News and the New York Post, citing unnamed law enforcement officials, reported that federal investigators are examining whether Mullins misused union accounts.

Mullins resigned as union president that evening and hasn’t commented publicly since the raids. A call to his cell phone went straight to voicemail, and the mailbox was full. In a note to members, the union’s executive board wrote that Mullins “is apparently the target of the federal investigation” and that it had “no reason to believe that any other member of the SBA is involved or targeted in this matter.”

Mullins’ lawyer, Marc Mukasey, didn’t respond when asked if Mullins has been told he is a target of the federal inquiry. Federal prosecutors can deem someone a “target” when investigators have collected “substantial evidence” that links the person “to the commission of a crime,” according to the Department of Justice manual.

No charges against Mullins have been announced by the U.S. attorney’s office in Manhattan, which is leading the investigation and which, along with the FBI, declined to comment for this article.

But to critics of the police unions, the incendiary, unchecked rhetoric from Mullins and the scant oversight of the SBA’s finances underscore the influence the unions have amassed and the power they have to obstruct reform.

“It’s a problem in the police world, not unsimilar to the civilian review board, where there’s just nobody who wants the ire of the police union because they’re so bananas half the time with their public relations stuff,” said Bruce McIver, who served as the chief labor negotiator to Mayor Ed Koch from 1979 to 1983 and spent decades in city and state government.

While the federal inquiry moves forward largely behind closed doors, the NYPD has over the last several months gone public with action against Mullins over his crude rhetoric and combative tactics.

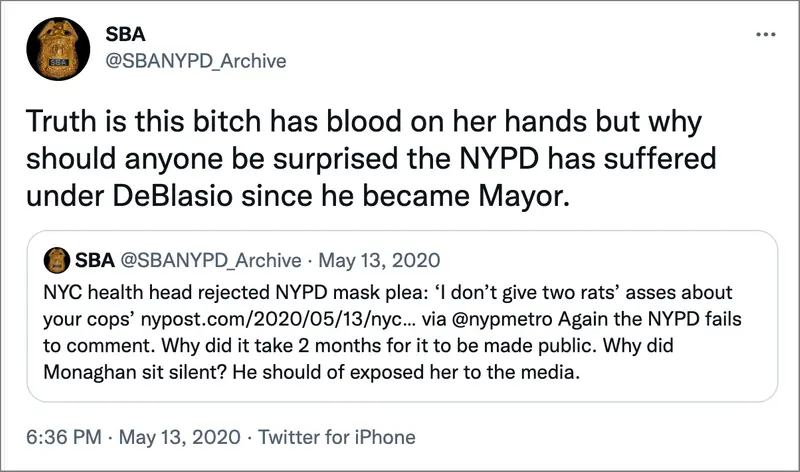

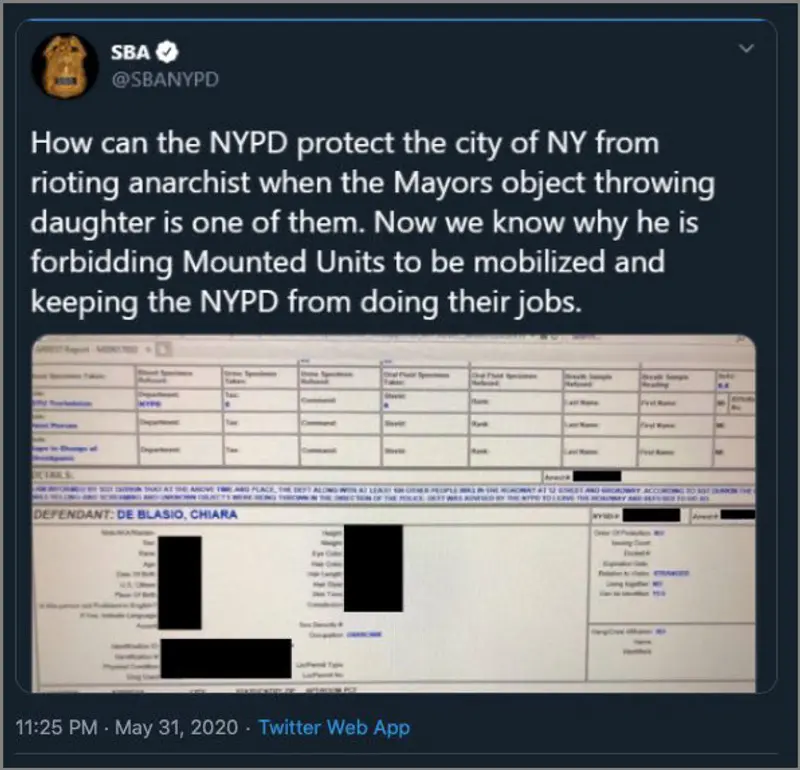

Early this year, Mullins was brought up on departmental charges for tweets he sent in 2020. Two tweets used crass and vulgar language to target city officials who had been critical of the police. Another disclosed the arrest record of the mayor’s daughter, who was detained during racial justice protests that followed George Floyd’s 2020 murder. Mullins sued to stop the disciplinary proceeding, arguing his statements as a union president were protected by the First Amendment, but a federal judge denied his request.

In late October, Mullins appeared before a departmental tribunal to face charges of abuse of authority and making disrespectful remarks. On Nov. 5, the police commissioner docked Mullins 70 vacation days for his online behavior. Mullins, 59, retired from the Police Department that day, after 39 years with the department.

The internal discipline was a far cry from being fired, as some critics had urged, and the punishment won’t affect his ability to collect a pension on the $133,195 salary he earned in 2020 as an NYPD sergeant.

But if the NYPD let Mullins leave the department largely unscathed, the stakes are decidedly higher with the FBI and the U.S. attorney’s office.

Mukasey, Mullins’ lawyer, declined to comment on the federal investigation, saying only that the October search warrants executed on Mullins’ home and the SBA headquarters were the result of a “brand new'' inquiry by federal prosecutors. He didn’t respond to questions about past allegations made against Mullins.

At least three times over the last decade, local or federal investigators have received claims that Mullins was exploiting his role as SBA president and a member of the NYPD, according to a spokesperson for a city agency that received an allegation, a retired Long Island police officer and four people with knowledge of allegations who spoke on condition of anonymity to provide confidential details.

In one instance from 2011, a tipster detailed to investigators claims that Mullins had misappropriated union funds and accepted gifts in exchange for favors. A year later, the NYPD was notified after Mullins tried to intervene in the late-night arrest of an associate who had been pulled over for driving drunk on Long Island, according to a former law enforcement official and the now-retired officer who conducted the stop, Michael Palazzo. And in a third incident from around that time, police on Long Island alerted the NYPD that they had responded to a 911 call reporting a “domestic” incident involving Mullins, according to two former law enforcement officials with direct knowledge of the report to the NYPD. There were no arrests in connection with the incident, which involved a confrontation with a neighbor, the officials said.

Claims that Mullins had misappropriated union funds were later raised publicly, when, in 2014, a union board member challenging Mullins for presidency of the SBA made similar charges in a letter to union officials that was obtained by The Chief, which covers municipal labor issues. Mullins denied them at the time, and chalked them up to union politics.

But in New York City, where every year more than $1 billion in taxpayer dollars flow into union-administered funds, the chief financial officer can, at any time, examine accounts that collect public moneys. That entity, the Office of the City Comptroller, didn’t conduct an audit after the 2014 allegations were made.

In fact, the comptroller’s office hasn’t audited an SBA fund since 2003.

McIver said oversight of the police unions and their finances is too fragmented and too prone to political considerations.

“It’s a hole in the oversight apparatus in city government,” he said.

The SBA’s general counsel, Andrew Quinn, did not respond to questions from ProPublica about the current federal investigation or the past allegations about Mullins.

The risks associated with taking on the union were not lost on the Police Department. Indeed, it was the NYPD’s scrutiny of Mullins’ union years earlier that prompted the federal judge’s 2009 rebuke, court records show.

At issue then was whether the sergeants in Mullins’ lawsuit for overtime pay had lied under oath during depositions taken in the case, as city lawyers said they suspected in court filings. Making a false statement in an official proceeding is a potentially fireable offense, according to the internal rules for NYPD officers.

But the union saw the resulting internal affairs probe in the midst of a labor lawsuit as a retaliatory strike, and argued in court papers that sergeants serving as plaintiffs in the case were threatening to drop out of the litigation for fear of disciplinary action.

In her ruling, then-United States District Judge Shira Scheindlin sided with the union, barring the NYPD from finishing its false-statements inquiry and telling Mullins’ members that they could “rest assured that they may actively participate in this case without fear of retaliation.”

Two years later, internal affairs investigators learned of the allegations of misuse of union funds by Mullins. And as investigators and city officials debated how to proceed, Scheindlin’s decision loomed large, according to two people involved with the case. One said the order had a “very chilling and dramatic effect” on the city.

A former law enforcement official said the NYPD alerted the Department of Investigation, the city’s anti-corruption agency, to the misappropriation allegation, and in separate communications to the two other claims about Mullins. An NYPD spokesperson declined to comment on the past allegations about Mullins, citing the federal investigation.

Diane Struzzi, a spokesperson for DOI, said in a statement that in 2011 the agency received allegations of misappropriation of funds at the SBA but that it didn’t have a record of receiving complaints that Mullins had attempted to interfere in a DWI arrest or about the 911 call to which police on Long Island responded.

DOI, which investigates allegations of corruption by city workers or misuse of public funds, wouldn’t typically pursue misconduct claims like the ones made against Mullins, Struzzi said. The inspector general for the NYPD, created eight years ago and housed within DOI, generally looks at broad, structural issues involving the department.

Struzzi said the 2011 claims of union fund misuse were referred to federal labor investigators who she said were more suited to assess them.

Marjorie Franzman, who was the special agent in charge of the U.S. Department of Labor’s Office of Inspector General in New York at that time, said she didn’t recall receiving a referral regarding the city’s police sergeants’ union. Franzman, who is now retired, said that “as a rule we would not get involved in municipal unions.”

Whatever uncertainty there may have been over jurisdiction among the NYPD, DOI and Labor Department, the city comptroller unquestionably did have the power to scrutinize how unions spend taxpayer dollars. The 107 funds administered by municipal unions take in about $1.3 billion in public funds every year, and since 1977 the comptroller has had the authority to examine their books and records.

The SBA is among the city unions that receive the largest allocations, according to an annual analysis the comptroller’s office publishes that compares the funds’ aggregate finances. As the union’s president, Mullins is a trustee of the SBA accounts that accept city contributions and has a role in managing the funds. They collectively received nearly $27 million from taxpayers in 2018, the agency’s most recently available analysis shows.

Robert Linn, who has twice led the city’s Office of Labor Relations, most recently from 2014 to 2019, said there has been far too little scrutiny of how city unions manage New Yorkers’ contributions.

“I have always thought, whether it’s the comptroller or the DOI, there should be more consideration of that, simply because there’s so much money,” said Linn, the city’s representative on a three-member arbitration panel that will be deciding a new labor pact with the SBA’s sister union, the Police Benevolent Association, which represents 24,000 NYPD officers.

Most unions, including the SBA, also maintain funds that don’t receive taxpayer money, including those underwritten by members’ dues and charities for the widows and children of officers killed in the line of duty that can accept donations.

Still, the funds that are eligible for city contributions are rarely audited by the comptroller, an elected official with a staff of 800 that’s charged with overseeing agency budgets, city contracts and hundreds of billions of dollars in pension funds.

The last time a comptroller examined a police fund was in September 2009, when officials reviewed a welfare fund for lieutenants and captains. ProPublica reported earlier this year that a city-financed, union-controlled legal defense fund for police officers was last examined by the comptroller in 1994.

In the past decade, the three officials to hold the comptroller’s post have all had eyes on higher office, each of them running, unsuccessfully, for mayor.

The newly elected comptroller, Brad Lander, was a proponent of police reform during his time on the City Council and had a hand in creating the inspector general for the NYPD. As a candidate for comptroller, Lander vowed to audit the NYPD to “examine why the department is failing to deliver improved safety outcomes.” But neither Lander nor his spokesperson responded to questions about whether the new comptroller will keep a closer eye on police union funds.

Press aides for state Sen. John Liu, who served as city comptroller from 2010 through 2013, declined to answer questions about scrutiny of union funds during his time in office.

And a spokesperson for the outgoing comptroller, Scott Stringer, who ran for mayor this year and lost in the Democratic primary, said that “in light of the ongoing federal investigation,” the office couldn’t discuss questions about auditing police union funds and why Stringer didn’t initiate an inquiry after a SBA board member publicly raised concerns about Mullins in 2014.

Stringer had been in office for about six months when the SBA board member, a sergeant named Robert Johnson, publicly questioned how Mullins was handling union funds.

In a letter to fellow board members, Johnson, the union's treasurer, claimed Mullins was misappropriating member dues and Widows and Children’s Fund moneys, including by buying plane tickets to the Super Bowl with an SBA credit card and writing $18,000 in checks to a neighbor who provided “fictitious” invoices, according to the story in The Chief. Mullins denied Johnson’s allegations and said Johnson had engaged in unethical behavior for which he was fired from the board. Mullins told the newspaper that Johnson was disgruntled and was “resorting to penny-ante crap because he has no platform.”

Reached by phone, Johnson, who retired from the NYPD in 2016, said in a brief interview that no law enforcement investigator or city official interviewed him about his claims but that he believed Mullins was now experiencing “karma.”

Even so, he said, “I wouldn’t wish the FBI on my worst enemy.”