ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for Dispatches, a newsletter that spotlights wrongdoing around the country, to receive our stories in your inbox every week. This story was co-published with the USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin.

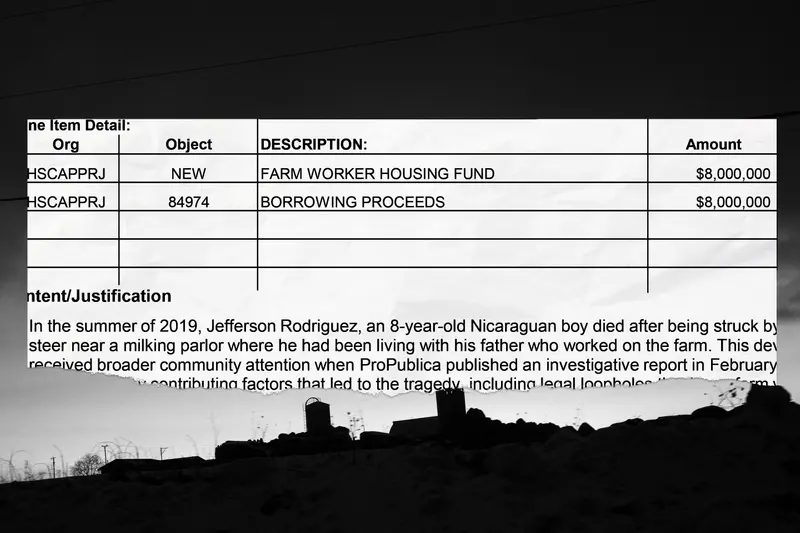

County officials in Wisconsin approved reforms this week meant to respond to a ProPublica report on the flawed investigation into the 2019 death of a Nicaraguan boy on a dairy farm. They include an $8 million fund for farmworker housing and measures to improve access to government services for people who don’t speak English.

Advocates said the housing initiative appears to be the first of its kind in Wisconsin, a state that calls itself “America’s Dairyland” but that offers few protections for the undocumented immigrants whose labor many farms depend on.

Separately, the sheriff’s office in Dane County — which investigated the boy’s death — has drafted its first-ever written policy on how to respond to residents with limited English proficiency.

The changes come in response to a February report by ProPublica that detailed the flawed law enforcement investigation into the death of Jefferson Rodríguez, an 8-year-old boy who had lived in a barn above a milking parlor on the farm where his father worked about a half-hour north of Madison.

ProPublica found that another worker had accidentally run Jefferson over with a skid steer, a piece of machinery used to clear manure off barn floors. But the deputy who interviewed the boy’s father, José María Rodríguez Uriarte, mistakenly concluded that he had been the one operating the machine. This failure, we found, was due in large part to a language barrier. Jefferson’s death was ruled an accident, but Rodríguez was publicly blamed.

In a recent interview, Rodríguez said he was glad to learn that the story of what happened to his son has led to changes that could help other immigrants. “Perhaps if all of this had happened five or six years ago, my situation would have been entirely different,” he said. “It would be much better to be able to communicate with police without the fear of calling and them not understanding.”

The measures were approved Monday as part of the county budget. Joe Parisi, the county executive, can still veto the budget but is not expected to do so.

After our story was published, several members of the board and other elected officials began calling for measures to ensure that people who don’t speak English can communicate accurately with sheriff’s deputies.

When Jefferson died, the sheriff’s office had no written policy on what deputies should do when they encountered people who spoke limited English or when they should call for an interpreter. As a general practice, the department encouraged patrol deputies to ask for help from bilingual colleagues or to use a phone- or video-based interpreter, Elise Schaffer, a department spokesperson, said in a statement.

The department doesn’t test language skills of employees, who instead self-report proficiency.

The deputy who interviewed Rodríguez identified herself as a proficient Spanish speaker. When we interviewed her, however, we discovered that the words she used in Spanish to question Rodríguez didn’t mean what she thought. Rodríguez told us that he never understood the deputy was trying to ask if he was driving the machine that killed his son.

Sheriff Kalvin Barrett declined interview requests. But at a county board meeting in September, he acknowledged “shortfalls in the services that we have and we want to make sure that we’re continuing to provide individuals with the help and the services that they need, especially if they don’t speak English.”

Barrett said the department will test employees on their ability to speak a second language and that it was looking for ways to provide “additional financial support” to those who demonstrate proficiency. According to a draft policy, the department will provide training to staff on how to find qualified interpreters and ensure key documents and forms are translated.

Schaffer said she did not know when the draft policy would be adopted.

Law enforcement agencies that receive federal funding, like Dane County, are required by the Civil Rights Act to ensure that their services are accessible to people who speak limited English. ProPublica found that sheriff’s departments across Wisconsin routinely encountered language barriers when responding to 911 calls from dairy farms. Over and over, records showed, officers who couldn’t communicate with Spanish-speaking workers relied on farm supervisors, other workers, Google Translate and even children to interpret for them.

The Board of Supervisors on Monday separately approved the creation of three full-time positions and one part-time role to improve services for people who don’t speak English. Among them: a coordinator to help departments implement language access plans and engage community members with limited English proficiency.

Dana Pellebon, a member of the Board of Supervisors who chairs the county’s Equal Opportunity Commission, said the issue of language accessibility got more attention than ever this year.

“Your article started this investigation into what it is that needed to happen,” she said. “I am deeply sorry and ashamed that it had to take the death of a child for us to be aware, and we’re going to work proactively to make sure these situations never occur again.”

ProPublica’s reporting also put a spotlight on dairy worker housing, which goes largely unregulated and uninspected by state and federal authorities.

Dane County is home to more than 170 dairy farms, according to state records. It’s unknown how many provide housing to workers, but a recent statewide study on immigrant dairy workers by the University of Wisconsin-Madison’s School for Workers found that close to three-quarters of surveyed workers lived in employer-provided housing, typically on the farm.

Our reporting found that Jefferson and his father had lived in a room above a milking parlor — the place where cows are milked day and night with loud, heavy machinery. (In court filings, the farm’s owners disputed that they lived there. ProPublica spoke with more than a half-dozen people, including Jefferson’s bunkmate, who confirmed that they and other workers lived above the parlor.)

“The issue of safe housing for folks working on farms and in rural parts of the county I don’t think had been front of mind to me until hearing more about, honestly, the death of Jefferson Rodríguez,” said Heidi Wegleitner, a member of the Board of Supervisors who was the lead sponsor and author of the farm worker housing initiative. “This is a gap that existed, I think, before your important reporting, but it really gave me a sense of urgency about doing something about it.”

Wegleitner, who is also a housing attorney, said the first goal of the new initiative will be to assess the existing housing supply and needs of farm workers. The county could then purchase land and build new housing.

Advocates say there is a significant need for affordable housing for undocumented immigrant dairy workers who are excluded from existing programs due to restrictions in federal funding.

“This has always been a challenge for us,” said José Martínez, the chief operating officer of the nonprofit United Migrant Opportunity Services, which operates several affordable housing projects for agricultural workers across Wisconsin.

None of UMOS’ housing developments are accessible to people who are undocumented.

Neither is the 32-unit apartment complex for low-income agricultural workers that opened last year in Darlington, in southwest Wisconsin. Several people involved with the project said it was intended, in part, to serve immigrant dairy workers in the area, but instead the units have been mostly rented out to other kinds of agricultural and food-processing workers, including immigrants with work permits.

There are other challenges. For more than a decade, Wisconsin has barred undocumented immigrants from obtaining driver’s licenses, even though the state allows them to buy and register their vehicles. ProPublica reported earlier this year on how undocumented dairy workers are ticketed over and over for driving without a license. As a result, some workers prefer to live on the farms where they work so they can avoid having to drive.

Meanwhile, Rodríguez said he is glad somebody in Dane County is paying attention to the housing conditions immigrant workers encounter on dairy farms. It’s a subject he says comes up often when talking to friends who live and work in the area.

“The problem is you are just afraid that if you complain, there will be a negative reaction from the bosses,” he said. “That maybe they’ll tell you, ‘We don’t need you working here anymore.’ And so you just put up with the bad conditions.”