This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Oregon Public Broadcasting. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

To free salmon stuck behind dams in Oregon’s Willamette River Valley, here’s what the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has in mind:

Build a floating vacuum the size of a football field with enough pumps to suck up a small river. Capture tiny young salmon in the vacuum’s mouth and flush them into massive storage tanks. Then load the fish onto trucks, drive them downstream and dump them back into the water. An enormous fish collector like this costs up to $450 million, and nothing of its scale has ever been tested.

The fish collectors are the biggest element of the Army Corps’ $1.9 billion plan to keep the salmon from going extinct.

The Corps says its devices will work. A cheaper alternative — halting dam operations so fish can pass — would create widespread harm to hydroelectric customers, boaters and farmers, the agency contends.

“Bottom line, we think what we have proposed will support sustainable, healthy fish populations over time,” Liza Wells, the deputy engineer for the Corps’ Portland district, said in a statement.

But reporting by Oregon Public Broadcasting and ProPublica casts doubt on the Corps’ assertions.

First, some leading scientists have said the project won’t save as many salmon as the agency claims.

A comprehensive scientific review in 2017 concluded that the use of elaborate fish traps and tanker trucks to haul salmon, as the Corps proposes, will “only prolong their decline to extinction.”

Moreover, many of the interests the Corps says it’s protecting maintain they don’t need the help — not power companies, not farmers and not businesses reliant on recreational boating.

The Corps’ effort to keep its dams running full-bore is a story of how the taxpayer-funded federal agency, despite decades of criticism, continues to double down on costly feats of engineering to reverse environmental catastrophes its own engineers created.

The only peer-reviewed cost-benefit analysis of the Willamette dams, published in 2021, found that the collective environmental harms, upkeep costs and risks of collapse at the dams outweigh the economic benefits.

Congress has weighed in, twice calling on the Corps to study shutting down hydropower, which would free up more water for salmon. The agency blew its first deadline last year and now says it will perform an “initial assessment” to help decide whether to do the study required by law.

Emails obtained by ProPublica and OPB show that as Corps officials hashed out how to handle the mandate from Congress, they proposed actions that could increase public support for preserving hydropower. The Corps is now finalizing a plan that would continue electricity generation for the next 30 years.

“How can you finalize a long-term plan if you don’t know whether or not you’re going to continue hydro?” said former U.S. Rep. Peter DeFazio, D-Ore., who pushed for legislation ordering the Corps to study ending hydropower.

“They’re doing that without the study and the information they need,” he added.

Democrat Val Hoyle and Republican Lori Chavez-DeRemer, who now represent portions of DeFazio’s former district, said in separate written statements that it was urgent for the Corps to finish its study and no decisions on the Willamette should be made until that happens.

There is a simpler way to protect fish: opening dam gates and letting salmon ride the current as they would a wild river. It costs next to nothing, would keep the Willamette Valley dams available for their original purpose of flood control and has succeeded on the river system before. This approach is supported by Native American tribes and other critics.

The Corps ruled it out as a long-term solution for most of its 13 Willamette River dams, saying further reservoir drawdowns would conflict with other interests.

The debate and the consequences of the decision are real for the Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde, who have fished the Willamette for thousands of years. Grand Ronde leaders said they’ve met with the Corps seven times to spell out potential alternatives to building giant fish collectors and maintaining hydropower.

“They always feel like they can just build themselves out of problems. And this is really something that we don’t need to build,” said Michael Langley, a former tribal council member for the Grand Ronde.

The tribes have also said generating electricity at the dams doesn’t pencil out for anyone. By the Corps’ own estimates, the cost of hydropower over the next 30 years will outstrip revenues from electricity customers by more than $700 million.

The tribes filed a letter with the Corps in February that included a pointed summation: “Killing salmon to lose money deserves a deeper analysis.”

“Tooth and Nail”

Many of Oregon’s most populous and valuable places, like downtown Portland, would spend parts of the year underwater if not for dams.

Congress ordered the Army Corps to build the system during the 1940s, ’50s and ’60s to hold back floodwaters in Oregon’s fertile Willamette Valley. Towns sprouted up in the security of 300-foot walls. Lawmakers approved additional uses for the dams. The rivers they impounded provided places for people to drive power boats as well as deep pools of water to spin hydroelectric turbines. Today, eight of the 13 dams generate power.

But the monumental structures caused harm, too. Salmon evolved to swim and spawn in cold, free-flowing rivers that the dams choked into warm, stagnant lakes, full of bass and other invasive predators. Salmon need to get to the ocean and back, but the dam walls blocked their path. Whirring turbines bashed fish that attempted to scoot past.

In 2021, after salmon numbers on the Willamette reached historic lows, a federal judge said the fish’s recovery had been stymied far too long.

U.S. District Judge Marco A. Hernandez admonished the Corps for having “fought tooth and nail” against better measures for fish ever since it was first sued over the issue in 2000, foot-dragging that the judge said had pushed the fish closer to the edge of extinction.

Gates in the dam walls can provide a passage for young salmon to pass downstream, but they’re usually too deep underwater for the little fish to find because they stay near the surface. Those that do dive down to the deep gates can get the bends and die. The judge ordered the Corps to drain several reservoirs to levels lower than any since the dams were built.

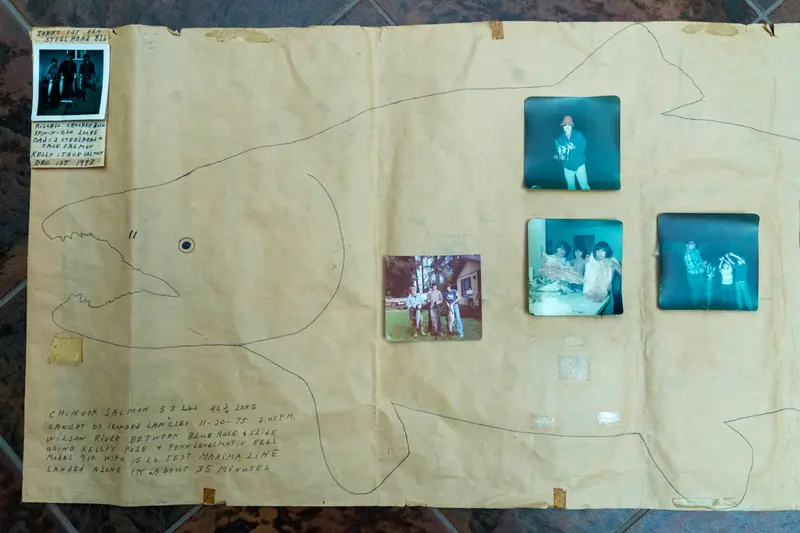

Scientists had observed that whenever reservoir levels dipped seasonally, more fish passed through dams. Knowing this, Corps biologists had been experimenting with draining a reservoir known as Fall Creek until it nearly replicated the original river channel.

The drawdown worked. It moved salmon quickly and safely past the dam and eliminated many of the invasive predators dwelling in the reservoir. At virtually no cost, the Corps increased the number of adult fish that returned tenfold, surpassing what biologists thought possible.

The Corps has argued that there are limits to this approach. Fall Creek’s openings are more fish-friendly than those at other dams. And Corps officials worried draining many dams all at once might trade one hazard for another, such as by leaving too little streamflow for fish.

But Hernandez ruled that the weight of the evidence showed drawing down reservoirs was “the most effective means for providing safe fish passage” and “necessary to avoid irreparable harm” to salmon. He ordered the Corps to try partial drawdowns at three other dams. Then he set a 2024 deadline for the Corps to have a new long-term plan to save salmon, which he expected to go even further than his order.

Tribes and environmentalists cheered the judge’s ruling as a long-overdue remedy.

But the Corps had its own ideas.

Building a Better Fish Trap

In 2022, the Corps released a draft of the document the judge had ordered: a 5,782-page environmental impact statement for Willamette dam operations.

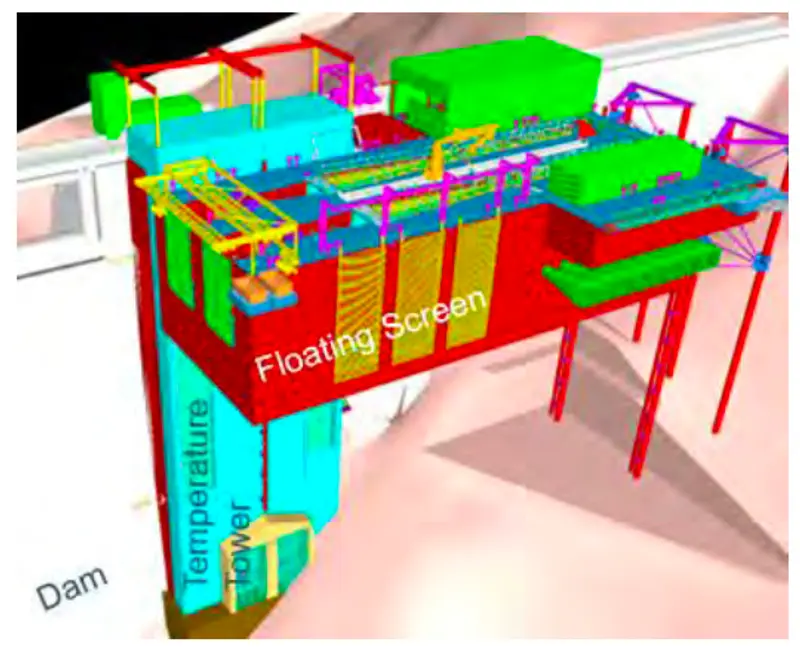

At the two dams that threaten salmon the most, the Corps would build complex structures called floating fish collectors.

Versions built elsewhere resemble industrial buildings atop the water, loaded with fish pens, electrical equipment and water pumps. The idea is for fish to mistake the whooshing current created by the pumps for the river’s flow and get lured into the trap.

Collectors that Corps envisions for Detroit and Lookout Point dams would cost a combined $622 million. In addition, the Corps would spend $432 million on an enormous water-cooling device at Detroit. Other money would buy smaller fish traps and habitat restoration.

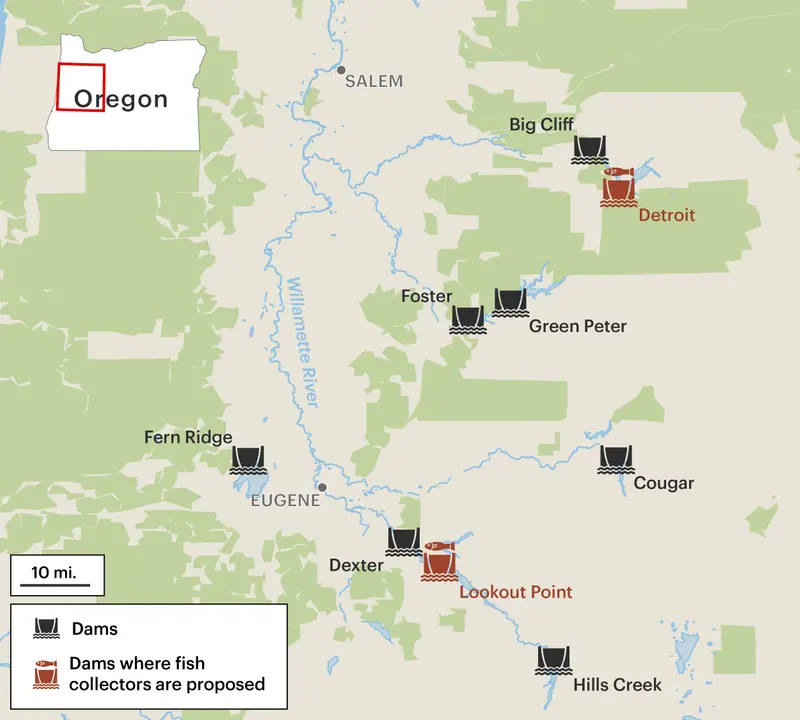

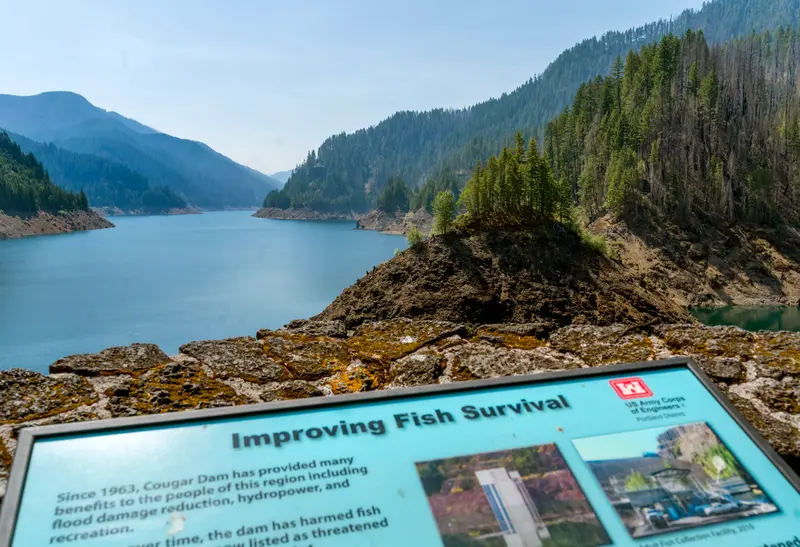

Hydropower Dams Block Salmon Migration in the Willamette River Valley

At two of the most crucial dams for salmon restoration in the Willamette Valley, the Army Corps of Engineers has proposed building massive fish collectors that suck in and trap young salmon, which would then be placed in trucks and driven downstream.

The Corps first tried a kind of floating fish collector on the Willamette in the 1950s but declared it a failure.

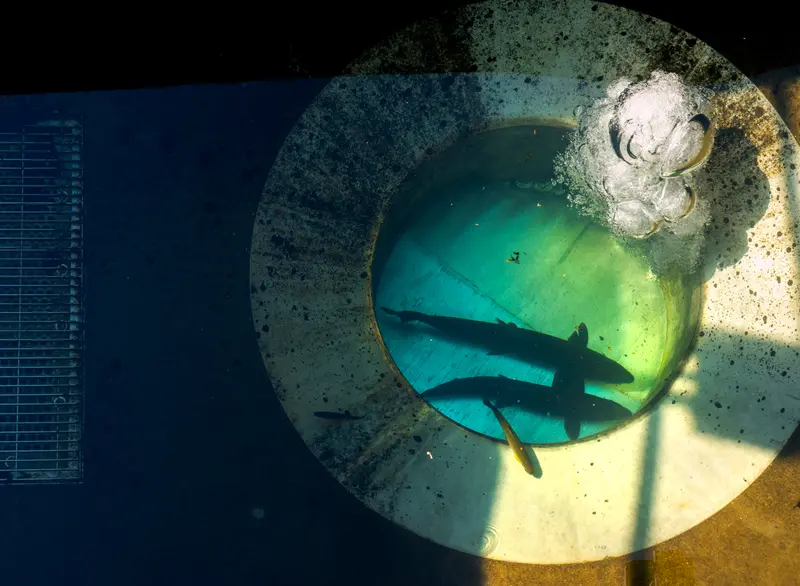

As salmon populations dwindled into the 21st century, the Corps decided to try again, building a small collector on an offshoot of the Willamette. To track the baby fish they were trying to entice, biologists implanted nearly 1,500 with microchips and released them behind Cougar Dam.

Eight found their way into the collector.

The agency ended the experiment ahead of schedule.

Floating collectors at other dams in the Northwest have shown better results. But at the location biologists consider most comparable to the Corps’ Willamette dams, it’s been a struggle. The fish collector on southwest Washington’s Lewis River captured just 3% of the Chinook salmon it was targeting, a peer-reviewed study found. The dam’s owner reported success rates as high as 33% in later years.

“You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to go back and look at how these structures performed in other locations to see that there’s been some challenges,” said Greg Taylor, the Corps’ supervisory fish biologist.

For this reason, the Corps did propose deep and sustained drawdowns at Cougar and Fall Creek dams.

But the number of fish helped would be relatively small because of these dams’ locations. By contrast, the dams where the Corps wants to try fish collectors wall off about 70% to 100% of the area where fish hatch. The Detroit and Lookout Point dams block rivers that once supported some of the valley’s most abundant fish runs.

The Corps didn’t consider these dams good candidates for a drawdown because of the way they were built and because Corps officials viewed their operations as too crucial to justify it.

So agency leaders commissioned a study of previous fish collector builds to devise improvements. They arrived at a plan for collectors five times as wide and five times as powerful as any ever evaluated. The structures at Detroit and Lookout Point would take a decade to complete.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which must approve the Corps’ actions before it can proceed, said in a statement its scientists “are confident that collectors can be effectively applied” as the Corps optimizes their design.

Big uncertainties remain, though.

Supersizing the collectors for better performance makes sense in theory, according to U.S. Geological Survey biologist Tobias Kock, who led the 2019 study. But because what the Corps is proposing is so much bigger than anything Kock and his colleagues looked at, he told OPB and ProPublica, “we don’t know how well that performance prediction’s going to work.”

The most successful floating collector in Kock’s study captured roughly 60% of Chinook salmon, on a reservoir with far more favorable conditions than on those the Corps owns. The Corps, meanwhile, estimates its supersized fish collectors will capture between 80% and 95%.

The Corps’ environmental impact statement acknowledges its numbers are a guess. It says the collectors the agency contemplates “have yet to be successfully implemented and there is considerable risk and uncertainty about the realized effectiveness of these structures.” In a September statement to ProPublica and OPB, Corps officials went further, calling their projected success rates “overestimates.”

University of California, Davis researchers Robert Lusardi and Peter Moyle published a 2017 study in the journal Fisheries warning that the kind of trap-and-haul programs the Corps has proposed “should proceed with extreme caution.”

Lusardi said in an interview that their success rates are artificially inflated and that removing young salmon from the river stresses them, increasing their risk of dying before they find their way home to spawn as adults.

“Transportation of fish, whether it’s juveniles or adults, has a really seismic effect on the fish themselves,” Lusardi said.

Rich Domingue, a former NOAA hydrologist who provided expert testimony for environmental groups that sued the Corps, said these flaws and others biased the Corps’ analysis in favor of preserving hydropower.

Instead, Domingue said, the Corps should be drawing down more reservoirs and closely monitoring the results, “rather than spending billions over decades in a high-risk gamble.”

“Human Error Fixing Human Error”

At the heart of the Corps’ push to find a technological fix for dams is its claim that people throughout the Willamette Valley cannot live without the hydropower, recreational boating and irrigation that the dams make possible. The trouble is, it’s hard to find people in the Willamette Valley who feel the same way.

Even the hydropower industry opposes the Corps’ plan to continue with hydropower.

Ending power generation on the Willamette would be “the best for consumers, the best for fish, and the best for taxpayers,” wrote Scott Simms, executive director of the Public Power Council, and Mark Sherwood, head of the Native Fish Society, in a joint 2021 letter published in the Eugene Register-Guard.

Records newly obtained by OPB and ProPublica via the Freedom of Information Act show the federal government’s hydropower agency for the region, the Bonneville Power Administration, also wants the Corps to do away with hydropower on the Willamette.

Bonneville, which pays roughly half the costs of operating Willamette dams, urged the Corps last year not to spend hundreds of millions of dollars to keep turbines running when cheaper solutions exist. The streams feeding the Willamette are wildly inefficient at producing electricity compared with dams on larger rivers, costing up to five times as much to light a home.

Similarly, farmers in the lush Willamette Valley are far less dependent on water stored in reservoirs than their counterparts in the high desert of eastern Washington, Oregon and Idaho, where current farming practices would be impossible without the irrigation that dams and reservoirs supply. The valley gets drenched with 50 inches of rain a year. Draining reservoirs each fall would have a marginal impact on water supplies downstream, according to the Corps’ own analysis.

The Oregon Water Resources Department said the drawdowns already happening under the court injunction have not undermined anyone’s ability to irrigate with water from the Willamette and its tributaries.

“It has no negative impact on me,” said Bob Schutte, owner of Northern Lights Christmas Tree Farm just downstream of two reservoirs that are already being drained each fall.

Lagea Mull runs the chamber of commerce for Sweet Home, a town that sits on a major route to Foster and Green Peter reservoirs. Mull said residents there want salmon to thrive and have adapted to the temporary drawdowns the judge ordered in 2021.

“When the dams came in, that was a massive change to the area,” said Mull, who knows people whose homes are now at the bottom of the reservoirs. “So now this is just another change.”

Linn County Commissioner Will Tucker is among the most vocal with concerns about draining reservoirs. But as a lifelong Willamette Valley resident, he also cares about the salmon.

“If it recovers the salmon,” he said of drawdowns, “it's the right thing to do.”

Tucker wants the Corps to help offset what he worries would be the biggest impact, to the river’s recreation economy. More than 2.5 million people take their power boats or kayaks or inner tubes out on the Willamette River system annually. Visitors inject enough money into marinas, restaurants and shops to keep some towns afloat all year.

But the Corps estimates the kind of limited drawdowns it studied and ruled out would leave boat launches high and dry only at the tail end of the boating season, reducing visits by about 7% and spending by $1.3 million.

One business owner, Dawn O’Donnell, has already adapted her boat rental shop to the shorter season brought by court-ordered drawdowns. She delivers kayak and paddle boards to lakes that haven’t been affected.

Still, she is skeptical that anything the Corps does can actually help salmon to recover.

“It’s kind of like human error fixing human error, after human error, after human error,” O’Donnell said. “How can we make it right now that we’ve ruined it?”

A View of the River

For the past two years, the Corps has been developing a response to the court order, in which Hernandez stated it was “abundantly clear” the agency needed to change its operation of Willamette Valley dams.

Yet top Corps officials openly acknowledge that they never intended to veer very far from the status quo. Preserving dam uses like hydropower generation and water storage was the goal of its court-ordered environmental impact statement.

Wells, the deputy district engineer for the Corps in Portland, said in an interview that the work that went into the document “isn’t really a planning process for us to change the way we operate.”

As long as the law authorizes uses like hydropower and boating, the Corps has to find ways to preserve them, she said, adding that future needs for the water storage that reservoirs offer will only grow as the climate warms.

“The people that work here are really trying hard to think of what the best ways are to tackle this really tough problem in the space we have,” Wells said.

One internal email obtained by OPB and ProPublica under the Freedom of Information Act reveals how the Corps hoped to build support for staying the course.

Kelly Janes, a Corps planner assigned to the congressional request for a study into ending hydropower, suggested to colleagues that the Corps produce a series of videos and perhaps a podcast showing that hydropower has many benefits. These might generate public comments in support for hydropower that the Corps could forward to Congress.

“The public and Congress are only hearing one side of the story from the Public Power agencies who think hydropower in the Willamette is no longer profitable and Environmental groups who believe that hydropower deauthorization could be a silver bullet for the endangered species issues at our dams,” Janes wrote colleagues in April.

Asked to explain the Janes email, Corps officials denied they were trying to shape public opinion about hydropower. They said they wanted to make sure the public understood the complexities of hydropower and how integrated it is into their dams.

As for why the Corps is locking in a 30-year plan that preserves hydropower before studying an end to it as Congress ordered, the agency cited a looming deadline from Hernandez, the federal judge, and said the Corps has done the best it could in the time allotted.

Former employees and scientists who’ve worked closely with the Corps say its officials are afraid to change because drawing down reservoirs and eliminating hydropower would call into question the agency’s usefulness in the Willamette Valley.

“They don’t like to be seen as an agency that can’t execute,” said Judith Marshall, who spent six years as an environmental compliance manager for the Corps.

Marshall, whose work included projects in the Willamette Valley, filed a complaint with the federal Office of Special Counsel in 2017 alleging the Corps ignored obligations under federal environmental laws.

“They’re some of the smartest people I’ve ever encountered,” Marshall said, but “they’re so wound up in their models and what they’re doing, like they can’t see the forest through the trees.”

From her office in downtown Portland — with a sweeping view of the Willamette and the mountains beyond it — Wells mused on the possibility the Corps might someday take a broader look at what the region really needs from its dams and whether it should allow the river to run more naturally.

“Maybe that’s where this is all going in the future,” Wells said.

For now, the Corps has a $1.9 billion fish plan to finish.

Jan. 23, 2025: This story originally included a photograph whose caption misidentified a dam. It was an image of the Detroit Dam, not the Lookout Point Dam.