Early one morning in June 2022, Earl Westforth sat down at a small table inside a hotel conference room in northwest Indiana and began defending his life’s work.

Fourteen months earlier, the city of Chicago had sued his namesake Westforth Sports Inc., alleging that the outdoor- and sports-equipment shop was negligent in how it screened gun buyers and had become an epicenter for the unlawful purchase of guns, which were flooding into the violence-wracked city.

Over 50 years, Westforth had helped grow the Indiana business into one of the state’s most successful gun retailers. Operating from a squat building located just a few miles from the Illinois border on land set between downtown Gary and its richer suburbs, Westforth Sports raked in millions selling ammo, fishing gear and, most notably, guns.

Over eight hours, lawyers representing the city peppered Westforth with questions about how he and his staff handled situations in which a customer tried to purchase a gun for illegal use or resale on the underground market. Westforth explained how he looked for signs of bad intent: cash being exchanged between two customers, or a customer who clearly was drunk or high.

But as he said time and again, often the decision came down to something less tangible.

“Gut feeling is one of them,” he said at one point.

“It’s a gut reaction,” he said at another.

And: “You just feel like something’s not right.”

He later elaborated: “The way their — eye movement, who they’re with, nervous.”

If customers did raise suspicion, the store’s process for keeping track of them was far from precise: Employees wrote notes with their observations and suspicions, then posted them at the store’s cash register. How long the notes remained there varied.

Sometimes, the notes were discarded at the end of the day, Westforth said. If the customer was someone an employee wanted to keep track of beyond one day, the note was moved to a back office.

“Certain ones we keep,” Westforth testified, “depending on how we feel.”

But there was no guarantee that his employees would check the back office for a note if the customer returned, he acknowledged. No rules for how long to keep those notes. No rules for maintaining what he called the “be on the lookout” list. No comprehensive system at all for spotting problem customers.

More than 60,000 retail stores and pawn shops sell firearms in the United States, according to the most recent federal data. This glimpse inside one, as provided by Westforth himself in the 2022 deposition and in other records, puts in stark relief the weakness of government safeguards designed to keep guns from slipping into illicit markets and into the hands of criminals.

Guidelines set by the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives, the federal agency that oversees gun retailers, expects licensed owners like Westforth to act as the first line of defense in stopping the flow of illegal guns into vulnerable cities and towns. But with little financial incentive to forgo transactions and limited administrative penalties for failing to prevent illegal ones, some retailers have proven incapable or simply unwilling to play gatekeeper.

Earl Westforth personally has remained silent over the years even as he faced legal battles, scrutiny from federal agents and heaps of public criticism. Ultimately, he was able to leave the gun-selling business on his own terms, announcing his retirement over the summer. He did not respond to repeated requests from ProPublica for comment.

In his deposition, the details of which have not previously been reported, Westforth portrayed himself as a well-intentioned business owner who adhered to the letter of the law. He said that over the years, he and his employees went “overboard” to prevent illegal sales and keep guns out of the wrong hands, many times rejecting potential customers.

But in the deposition, Westforth was forced to address how his methods failed to prevent straw sales — where a firearm is purchased with the intent to resell it, most often to someone who is prohibited by law from purchasing guns.

One notable example involved Darryl Ivery Jr., an Indiana resident who in 2020 purchased 19 firearms from Westforth, spending over $10,000 in just six months. Ivery, who later pleaded guilty to making false statements on federal background check forms in relation to the 2020 purchases, took most of those firearms about 12 miles west of Westforth’s shop and across the state line to Chicago, selling them illegally for profit.

It’s totally legal. Maybe the guy just likes guns.

Despite Ivery regularly purchasing multiple guns and paying with cash — red flags for straw sales and gun trafficking, according to law enforcement — Westforth and his employees welcomed Ivery’s business again and again.

Asked in the deposition whether Ivery’s string of purchases should’ve raised concerns inside his store, Westforth hedged, pointing out that retailers are not required to determine someone’s intent before selling them firearms.

“It’s totally legal,” he said. “Maybe the guy just likes guns.”

It’s impossible to know how many guns trafficked by Ivery may still be in circulation. But several that have been recovered reveal a pattern that begins at Westforth Sports and ends on the streets of Chicago, where retail gun shops have been effectively prevented from opening inside city limits.

City police confiscated one 9 mm handgun purchased by Ivery from a teen found breaking into a South Side apartment. They collected another 9 mm from a man accused of brandishing the gun at a motorist during a traffic dispute. Officers responding to reports of a March 2020 shooting found a teen in possession of a .40-caliber handgun purchased by Ivery, this one bought at Westforth Sports less than 30 days before.

All three were arrested and charged with illegal possession of a firearm.

For years, Chicago officials have loudly complained about the gun retailers in nearby Illinois and Indiana towns whose shops are the source of illegal guns they say continue to fuel the crime and gun violence that have long plagued the city.

Studies by the University of Chicago found that Westforth Sports was the third-largest supplier of guns recovered by Chicago police. The research, which was conducted in cooperation with the city and focused on 2009 to 2016, linked just over 850 such guns to Westforth.

“These eye-popping numbers are not the result of bad luck or coincidence or location,” Chicago alleged in the complaint explaining its case. “They are the natural and predictable outcome of a business model that maximizes sales and profits by facilitating straw purchases and other illegal gun sales.”

The ATF views retailers as partners empowered with the discretion to decline any potential transaction they find suspicious, according to the agency’s best practices guide for retailers. That approach, as demonstrated by the transaction history of Westforth Sports and other retailers, has not halted gun trafficking.

At least 53 people, including Ivery, were indicted on federal gun trafficking charges over guns purchased at Westforth Sports between 2011 and 2021, according to a filing in the suit, which sought to compel Westforth to tighten store policies and pay unspecified monetary damages.

In May, less than a year after Westforth’s deposition, a county judge dismissed the suit, ruling that the Indiana business could not be sued in Illinois. The city has since appealed the court’s decision.

A decade ago, the ATF came close to forcing Earl Westforth to shut his doors.

After Westforth barely avoided losing his license a year earlier, a 2012 inspection found lingering problems. Agency interviews with Westforth employees, along with a review of the shop’s sales records, revealed repeated clerical errors and several serious breaches of federal gun laws.

Among them: After a customer failed a federally required background check, the shop allowed a person accompanying him to purchase the gun on his behalf.

A customer can buy as many [guns] as they want, It’s not our job to tell him no.

In response, inspectors recommended revoking Westforth’s license — just as they had in 2011. But a more senior agency official again opted for a “warning conference” to help correct Westforth’s lapses and ordered a follow-up inspection.

As part of the conference — one of three that ATF has required for Westforth since 2007 — Westforth’s employees, at his request, underwent a two-hour training session provided by the ATF covering proper record-keeping to prevent straw purchases. Yet the shop continued to rack up violation after violation in the following years.

Those violations led to citations and harsh words from the agency, including letters warning that “future violations, repeat or otherwise, could be viewed as willful and may result in the revocation of your license.” But the agency continued to grant Westforth additional chances.

In 2017, inspectors determined that Westforth was keeping incomplete records and had made a sale without conducting a background check or verifying the customer’s identity, as required. Then, in 2021, inspectors found a wide range of violations.

Westforth employees, the ATF report concluded, had again violated federal guidelines by failing to report to the ATF sales where customers purchased multiple guns — a key component of the agency’s anti-trafficking efforts. As they combed through the shop’s records, inspectors found the source of the problem. Westforth employees had been submitting the forms by fax,which had led to several failed submissions. The inspectors later urged Westforth to submit the forms by email.

Westforth employees also continued to have problems fulfilling their role as caretakers of federal records. ATF agents witnessed an employee “rip up and discard” two purchasing forms containing customer information after a sale fell apart because buyers were using a credit card with someone else’s name. Information on those potential buyers could have been useful to agents trying to trace straw sales or guns intended for crimes.

Westforth initially denied that his employees were discarding the forms, which federal guidelines require retailers to maintain. Then ATF agents audited the shop’s records and found that additional forms were missing.

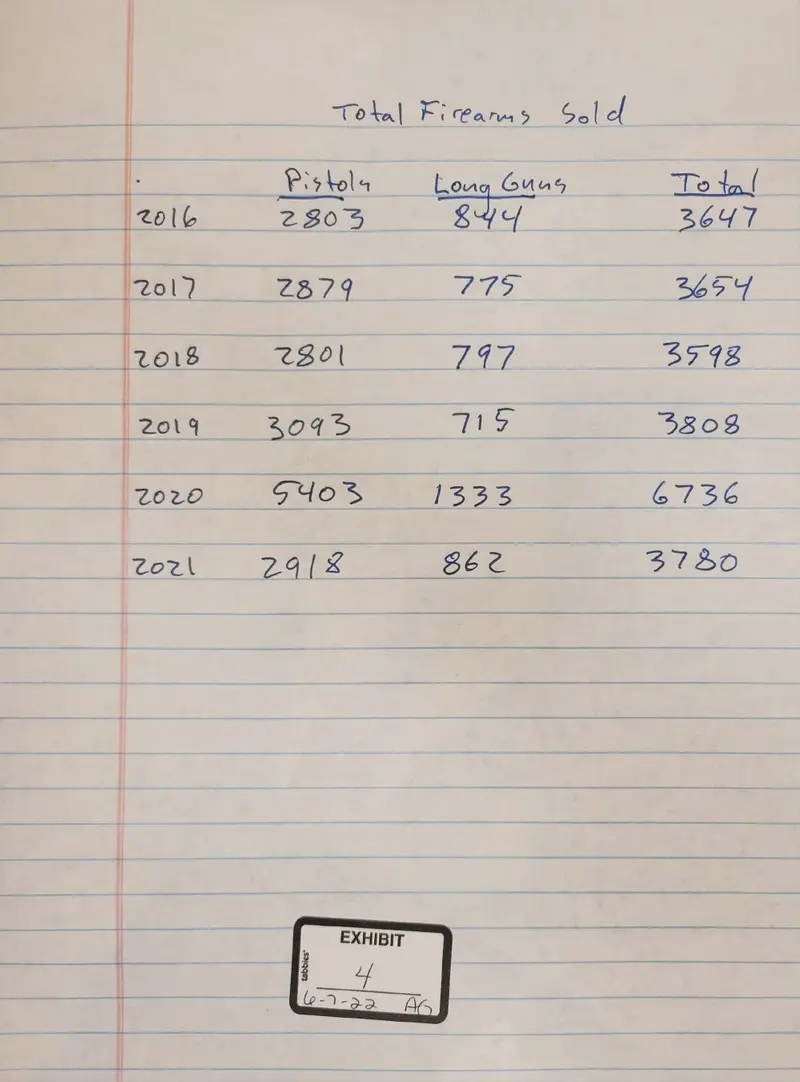

Meanwhile, sales at Westforth’s shop had reached a high. He told ATF inspectors that in 2020, as the pandemic peaked and civil unrest over police misconduct spread, customers began to “line up out of the store, across the parking lot and down the block” to purchase guns. That year Westforth’s annual sales of about 3,500 guns nearly doubled.

Agents remarked how the store was always busy. “The parking lot was always full and numerous customers were always present at any given time,” the ATF report said. “There were always vehicles present with out of state, Illinois, license plates.”

Westforth also described in his deposition how he handled an important task required by ATF — so-called “trace” requests, or instances where a law enforcement agency asks the ATF to track down the source and purchase history of a gun. This is potentially important information if in fact the person who police confiscated the gun from was not the one who initially purchased it.

But instead of researching in response to the requests, Westforth’s employees typically answered without consulting records, he said.

Memory sufficed, Westforth testified. And later, if that same buyer of the traced gun walked into the shop and wanted to buy another firearm, Westforth wasn’t particularly concerned.

“A trace, as explained to us by the ATF, could be for numerous reasons,” he said. “It doesn’t mean he’s a bad person.”

Multiple guns purchased by such a person wasn’t a concern either, despite federal guidance saying gun retailers should be on alert for customers who purchase several guns in one transaction. “A customer can buy as many as they want,” he said, adding, “It’s not our job to tell him no.”

That’s up to the ATF, Westforth said. But, in fact, the ATF does rely on gun retailers to assist by providing accurate paperwork and, in some cases, denying sales when there are clear signs or a reasonable belief of illegal intent.

ProPublica asked Edgar Domenech, a former ATF chief operating officer, to review Westforth’s deposition and his inspection record. He was taken aback.

“His license absolutely should have been revoked back in 2011,” said Domenech, whose 25-year stint at the ATF spanned both Democratic and Republican presidential administrations. “What he’s saying, the processes he talks about, they’re sloppy at best. This was a golden opportunity to correct his bad behavior, but the agency fumbled it.”

The ATF declined to comment on its inspections of Westforth Sports or their outcomes.

“ATF’s core mission is to protect the public from violent crime, particularly crimes involving the use of firearms,” it said in a statement to ProPublica. Enforcing federal laws and regulations is “critical” to that mission, the agency said.

But Peter Forcelli, a former ATF deputy assistant director, said that retailers typically only face penalties if they knowingly allow straw purchases, and proving that is difficult. Plus, scrutiny of retailers is limited by a shortage of ATF compliance inspectors, he said.

No more guns will come up there [to Chicago]. Hopefully not from me.

The shortfall represents a “substantial challenge,” the ATF acknowledged in its statement. The agency employs about 800 inspectors. That’s not enough to meet the agency’s own goal of inspecting each licensed gun seller every three years, it said.

Moreover, said Forcelli, straw sales have been considered a low priority by some federal prosecutors. “It’s a jacked-up system,” he said, “but we can’t put it all on retailers.”

Gun dealers rarely lose their licenses. In fiscal year 2022, the last year for which there is complete data, less than 1% of the nearly 7,000 compliance inspections of federal licensees resulted in a revocation.

Vowing to get tougher on lax retailers, the Biden administration in 2021 announced a far stricter policy in which even one serious violation would result in the ATF moving to revoke a license. Multiple inspection reports on Westforth Sports include a violation that fits that description.

Chicago was’t the first city to sue Westforth Sports seeking remedies to gun crime and violence.

In 1999, the city of Gary filed a sweeping suit against gun manufacturers and local gun shops, including Westforth Sports, claiming the retailers chose to overlook obvious straw purchasers. Gary’s suit has wound its way through the state’s court system and continues to this day.

But cases against retailers and manufacturers are difficult to prove — in part because while retailers may make questionable sales, it can be difficult to show that those actions were intentional or negligent.

Westforth Sports and the city came to an undisclosed settlement in 2008, so the retailer was dropped from the case. Still, attorneys for Gary continue to hold up the shop’s sales history as evidence of industrywide negligence in preventing gun trafficking.

A 2004 analysis commissioned by the city of Gary examining a decade of sales records identifies over 100 Westforth customers who engaged in sales that exhibited red flags associated with straw purchases. More recently, the sides continue to battle in court over what records can and should be disclosed, with the city requesting more recent gun sale information from Westforth and other area retailers.

For its suit against Westforth, Chicago enlisted the help of Everytown for Gun Safety, a national nonprofit, and compiled a roster of straw buyers like Ivery who had purchased from the shop.

By 2021, with the city’s headline-grabbing lawsuit in full swing, Westforth had begun weighing retirement. He confessed as much to ATF agents during an inspection of the shop conducted that same year.

He’d taken over the shop, which opened in 1955, from his father, and had planned to pass it on to his sons, he told inspectors. But one of his sons had already left the company, and in the wake of the lawsuit and deluge of bad press that followed, the business had become “radioactive.”

By then he had already made one concession following the complaints from Chicago. Westforth Sports was no longer selling guns to Illinois residents.

He said in his deposition that after being sued by Chicago, he had changed policies. “Just too much going on up there,” he said.

In the back-and-forth with the lawyer for Chicago, Westforth explained, “Well, when you hear about the shootings, you see the stuff on the news.”

And then he elaborated: “No more guns will come up there. Hopefully not from me. I’m not going to do it anymore.”

Ultimately, just as he told ATF he would, he shut down his business. Chicago lawyers hailed it as a victory for public safety. Westforth touted it as an opportunity for customers, announcing a “retirement sale” to liquidate the shop’s remaining inventory.

“Don’t miss these amazing deals,” the announcement read. “Once they’re gone, they’re gone forever.”

Mariam Elba contributed research.