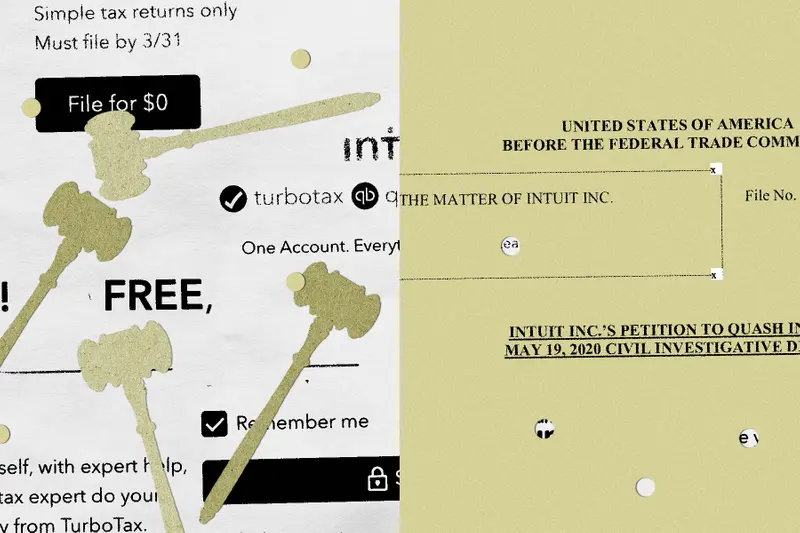

Faced with a class-action suit filed on behalf of customers who claim they were tricked into paying to file their taxes, TurboTax-maker Intuit knocked the case down. The company insisted its customers had agreed to forego their right to take their grievances to court and were required to use the private arbitration system instead.

But even as Intuit was winning in the class-action case, that very arbitration system was being weaponized against the Silicon Valley company.

A Chicago law firm is using a novel legal strategy by bankrolling customers bringing tens of thousands of arbitration claims against Intuit. Win or lose, this strategy could cost Intuit tens of millions of dollars in legal fees alone — a threat that could prod the company to be more open to a giant settlement.

Nearly three years after ProPublica first reported on how many customers wound up paying for TurboTax when they could have filed their taxes for free, Intuit is fighting a complex set of legal battles to stop consumers from trying to recover money.

Besides the huge number of consumer claims that have been filed, federal regulators and state-level prosecutors are also advancing efforts against the deep-pocketed company, which made $2 billion last year.

The most unusual front in the fight is the strategy to bring tens of thousands of individual consumer claims in arbitration, the alternative to the public court system that has historically been considered friendly to business.

The so-called mass-arbitration tactic was pioneered in recent years as the legal terrain became less friendly to class-action lawsuits, the traditional tool used to recover money for consumers through the court system.

The tactic is akin to using guerilla warfare rather than having soldiers mass on the battlefield and face each other in lines. The law firm pursuing Intuit, Keller Lenkner of Chicago, has generated attention for successfully using the strategy on behalf of delivery workers for DoorDash and Postmates.

Intuit has vigorously defended its practices, denying any wrongdoing in each case. It stresses that millions of people do file their taxes for free using TurboTax each year.

“Intuit was at all times clear and fair with its customers,” a company spokesperson said in a statement to ProPublica, adding that it “not only did not hide free filing options from consumers, Intuit helped drive the adoption of free tax prep by helping more people file their taxes free of charge than all other online tax prep providers combined.”

Following ProPublica’s initial stories, Intuit was first sued in May 2019 in federal court. The case centered on customers who had to pay after starting the filing process using TurboTax’s Free Edition.

At the time, TurboTax maintained the heavily advertised Free Edition alongside a similarly named Free File product. The Free Edition routed some filers to a version of TurboTax that charged them a fee based on which tax forms they had to file.

Meanwhile, the Free File product, which was offered as part of a partnership with the IRS, did not route users to paid products and was truly free for anyone making less than an income threshold. But it was difficult to find. At one point Intuit added code to its website that removed the product from online search engine results. (The company later removed those lines of code.) A subsequent investigation by the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration found that in 2019 alone, more than 14 million tax filers paid for online tax prep software from TurboTax and other firms that they could have gotten for free. That amounted to roughly $1 billion in revenue for the industry.

The 2019 lawsuit was a traditional class-action case, in which plaintiffs’ lawyers sue a company on behalf of an entire category of consumers who have allegedly been harmed. If the plaintiffs prevail or the company settles, millions of people may be eligible to get money from the defendant.

But for decades, corporate America waged a successful battle against class-action suits, seeking to narrow their use. In recent years, companies got help from the Supreme Court, which issued a series of decisions that smothered many class-action lawsuits by making it easier for companies to hold customers to binding arbitration agreements. When consumers, including TurboTax users, sign up for a service, the terms-of-service contracts they click on often contain a buried clause that has them agreeing to pursue any grievance through private arbitration, not a lawsuit.

Studies have shown that hardly any users actually read these sprawling contracts. TurboTax’s current terms-of-use agreement, which still contains an arbitration clause, runs to over 15,000 words of dense legalese.

Arbitrations are handled in a private forum outside the court system. Crucially for business defendants, those claims are not bundled together, as class-action cases are. This fundamentally shifts the economic incentives: If one customer was defrauded of $50, it’s not worth a lawyer’s time to pursue the case. The calculus is different if a lawyer can represent an entire class of 20 million customers who each lost $50.

“It’s been just catastrophic for consumers and workers,” said Paul Bland of Public Justice, an advocacy nonprofit affiliated with plaintiff-side law firms. “It has wiped away tons of very well-merited and powerful cases where companies clearly break the law and they just get away with it because of the arbitration clauses.”

Business groups have argued that arbitration is a “simpler and more flexible” alternative to lawsuits and that class-action cases have served mainly to enrich plaintiffs’ lawyers.

After more than a year of litigation and an appeal, Intuit effectively won the federal class-action case against it by relying on TurboTax’s arbitration clause. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the 9th Circuit ruled that TurboTax users had agreed to arbitration by clicking a “Sign In” button on the software that stated users agreed to the service’s terms of use. Those terms contained the arbitration clause.

In that clause, the law firm Keller Lenkner recognized an opportunity. The strategy pioneered by the firm essentially called the bluff of companies that required their workers and customers to settle claims via binding arbitration. It also took advantage of the fact that companies typically must pay fees to the private arbitration organization, running perhaps a few thousand dollars per case.

What makes the strategy even more unusual is that the firm does not have the typical pedigree of plaintiffs’ lawyers, who have long been a stalwart constituency of the Democratic Party. Keller Lenkner was founded by a pair of former clerks for Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy, a Reagan appointee; one also was a clerk for Brett Kavanaugh when he was a George W. Bush-appointed appeals judge.

If a handful of consumers pursue arbitration, the fees companies must pay amount to a rounding error. But if businesses are facing thousands of individual arbitrations — a tactic they didn’t anticipate — the potential fees quickly add up and companies can be pressured into settling. The strategy also requires deep pockets on the part of the plaintiffs’ law firm, since they advance money to their clients to cover a modest arbitration filing fee.

While the strategy has so far been used in only a small number of cases, an academic article on the phenomenon by Georgetown Law professor Maria Glover termed it a revolution of the civil justice landscape, “one in which virtually all Americans are subject to mandatory arbitration agreements with class-action waivers, and one wherein a broad swath of claims—for consumer fraud, racial discrimination, gender discrimination, wage theft, and workplace sexual harassment—have been all but eliminated.”

Keller Lenkner disclosed in a related court filing in 2020 that more than 100,000 consumers had sought individual arbitration against Intuit. The firm advanced the consumers several million dollars in filing fees.

Intuit has tried to stop the mass arbitrations. In late 2020, following the appeals court ruling that doomed the federal class-action lawsuit, the company offered to pay a settlement of $40 million in that case.

If the court had approved the class-action settlement, consumers who failed to opt out would not be able to pursue their arbitration claims. A settlement for the entire class of consumers could have knocked out many of the ongoing arbitrations for a relatively cheap price. Keller Lenkner objected to the settlement.

At a hearing before U.S. District Court Judge Charles Breyer, a lawyer for Intuit complained that “the Keller firm is able to threaten companies — Intuit’s not alone — into paying $3,000 in arbitration fees, for a $100 claim.”

Breyer questioned whether the proposed settlement was in the best interest of consumers.

“I did think when I looked at this, and saw that, really, that this was a way to avoid or otherwise circumscribe arbitration, that it seemed to be that Intuit was, in Hamlet's words, hoisted by their own petard,” Breyer said, adding, “I think arbitration is the petard that Intuit now faces.” His comments were first reported by Reuters.

Breyer rejected the settlement in March 2021.

Since then, the arbitrations have proceeded slowly.

Limited data disclosed by one of the main arbitration organizations covers cases resolved through the end of 2021. It offers a glimpse of the arbitration dynamics, showing outcomes in a handful of cases: Intuit won at least nine and consumers won five, with the arbitrator awarding consumers as little as $35 and as much as $3,348. Intuit has continued to win most of the cases this year, according to a person familiar with the claims.

In one case, Intuit had to pay the consumer’s attorney fees of $9,500. In another, the plaintiff’s lawyers had to pay Intuit’s attorney fees of $5,025. Arbitrators can order the plaintiff to pay the company’s attorneys’ fees if a claim is deemed to be frivolous.

The data also shows several dozen cases that were either dismissed or settled, without giving any detail on how much money changed hands, if any.

The biggest hit for Intuit was on the cost of the arbitration itself, with administrative fees totaling more than $220,000 for around 125 cases. At that rate, 100,000 cases would cost the company more than $175 million in fees alone.

Legal filings suggest Intuit may have already paid tens of million dollars in arbitration fees by now, but public records of the payments won’t be disclosed until more arbitrations are completed.

Intuit has argued that many of the arbitration claims are bogus, and a lawyer for the company dubbed Keller Lenkner’s tactic “a scheme to exploit the consumer-arbitration fee structure to extort a settlement payment from Intuit.”

The lawyer also asserted that many of the claims involve users who either didn’t use TurboTax or did use it but filed for free. More than 1,000 cases — likely ones that fall into one of those two categories — have been withdrawn by Keller Lenkner, the public data shows.

In part because arbitrations are conducted in secret, it’s difficult to tell much about the success of the strategy in past mass arbitrations. Keller Lenkner has previously said that in a recent two-year period it secured more than $190 million for more than 100,000 individual clients, an average of $1,900 per client.

In a separate case filed against Intuit by the Los Angeles city attorney and Santa Clara County attorney on behalf of California consumers, the two sides are still fighting over what documents and data Intuit has to hand over. Both sides recently proposed a trial date of July 2023, but it has not yet been finalized.

Meanwhile, the Federal Trade Commission and a set of at least five state attorneys general are still actively investigating Intuit. Tech news outlet The Information reported last month that the FTC, now led by progressive chair Lina Khan, was pushing forward with the investigation despite a recent Supreme Court ruling that trimmed the agency’s authority in such cases.

One FTC commissioner, Rohit Chopra, voted to proceed with the case before he left the agency last October. But Chopra’s vote was in place only temporarily, according to a person familiar with the matter. The rest of the commission did not take up the matter at the time. An FTC spokesman declined to comment.

This year, the IRS Free File program allows anyone making less than $73,000 last year to use tax prep software and file a federal return for free.

But the program, which was originally conceived as an alternative to the IRS offering its own free filing service, is entering its first year without the participation of the two titans of the online tax prep industry. In 2019 and earlier years, TurboTax and H&R Block together accounted for around two-thirds of all filings through the program, according to ProPublica’s analysis. Intuit announced last year it was leaving the program “to focus on further innovating in ways not allowable under the current Free File guidelines.”

Only much smaller and less recognizable companies like TaxAct, TaxHawk and TaxSlayer, which only hold a sliver of the overall market, remain.

Paul Kiel and Jesse Eisinger contributed reporting.