This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with The Seattle Times. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

MONROE, Wash. — For Michelle Leahy, it started with headaches, inflamed rashes on her arms and legs, and blisters in her mouth.

Some students and staff at Sky Valley Education Center, an alternative public school in Monroe, also had strange symptoms: cognitive problems, skin cysts, girls as young as 6 suddenly hitting puberty.

Leahy, like others, eventually became too sick to return to campus. She developed uterine cancer as her other symptoms escalated.

“Who would ever think that the job that you love was making you sick?” Leahy, 62, said.

She didn’t know it then, about seven years ago, but her classroom contained some of the highest levels of toxic chemicals found at Sky Valley. Inspections and environmental testing across campus found an amalgam of harmful environmental conditions, including very high levels of carbon dioxide, poor air ventilation and polychlorinated biphenyls, or PCBs, a banned, synthetic chemical that the Environmental Protection Agency has linked to some cancers and other illnesses.

School administrators, however, knew.

Health inspectors flagged problems on campus as early as 2014, a year before Leahy’s health began to fail. But even as parents complained, again and again, about suspected environmental hazards there, school officials offered reassurances that cleanup efforts at Sky Valley were successful.

Records obtained by The Seattle Times in a public disclosure request show that Monroe School District officials responded slowly, at times asserting, even in official reports to the EPA, they had cleared the campus of toxic material, though in fact it still lingered in buildings.

To this day, federal officials still are pressing Monroe schools to clear the campus of PCB-laden material and address other environmental hazards. And to this day, Sky Valley remains open.

Ultimately more than 200 teachers, parents and students would claim that exposure at Sky Valley made them severely sick with illnesses that have been linked to PCB exposure. The saga at Sky Valley unfolded in a remarkable lawsuit against the manufacturers of PCBs, producing some of the largest-ever jury awards for individuals exposed to the chemical.

The litigation revealed a startling gap in Washington state law — readily acknowledged by government officials in court documents — that allows environmental hazards to fester in schools and may have implications for older schools across the state.

State law requires health districts to inspect schools for environmental hazards and propose actions — but they are not required to enforce their findings. Although school districts are broadly required to maintain a healthy environment, they don’t have to act on all health recommendations.

And if inspections find certain toxic chemicals, including PCBs, state law doesn’t require administrators to notify parents, students or staff of the results.

As a result of those gaps, the Monroe School District and the health agency for the county, the Snohomish Health District, haven’t faced any penalties from regulators relating to Sky Valley.

It’s unclear if Sky Valley is an outlier or a bellwether among the roughly 9,000 school buildings in Washington because the state has not done a comprehensive survey of the environmental health of schools.

But seven years ago, state environment officials said they were “especially concerned” about schools’ potential to expose people to PCBs, which were banned by the EPA in 1979 but still remain in some structures built before then.

State Rep. Gerry Pollet, D-Seattle, said Washington’s state law is exceptionally weak when it comes to environmental health in schools, which he learned last year when he helped pass a law requiring testing for lead in school drinking water.

School districts have resisted mandatory testing and cleanup laws because they do not want to be held financially responsible for expensive remediation when it is demanded, Pollet said.

“If you have a contaminated gas station, we clean it up for the health of the community,” he said. “But if you have the same contamination inside the school building, we act like it’s exempt from our standards of toxic exposure and cleanup. And that is a really sad and serious failing of state policy.”

The Monroe School District did not respond to questions about conditions at Sky Valley and declined to make officials available for interviews, including its superintendent. School board members did not respond to requests for comment. Instead, the district directed The Seattle Times to a lawyer and a 456-page consultant’s report that defends the district’s handling of Sky Valley.

The report defends the district’s communication with parents and teachers about the unfolding problem and says officials addressed PCBs appropriately. It notes that, although Washington mandates that schools maintain safe conditions, “none of these requirements are specific to PCBs in building materials.”

Leahy eventually transferred out of Sky Valley to another school, as did several other teachers, before retiring to Spokane, where she now lives.

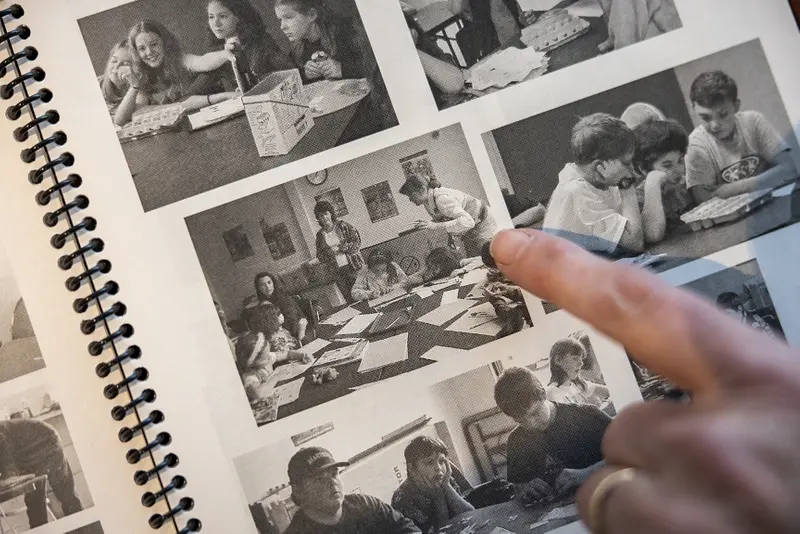

One memory is particularly haunting for her: setting up an inflatable planetarium once a week to teach immersive astronomy lessons to some of the brightest STEM students, about 20 at a time.

But with little air circulation inside the chamber, Leahy now believes her immersive lessons unwittingly intensified children’s exposure to harmful chemicals in the air and carpet. Many of her students became ill around this time.

“I had no idea,” she said, dissolving into tears. “I was poisoning my students.”

“And It Is Safe”

Monroe, a small city nestled near the Cascade foothills northeast of Seattle, is home to one of the largest public parental co-op programs in the state: Sky Valley Education Center. Launched in 1998, it offers K-12 students individual learning plans that include hands-on environmental science courses and self-directed Montessori instruction.

The popular, 700-student program once occupied a vacant warehouse. In 2011, it moved to an aging campus when the district consolidated middle schools, giving the program bigger classrooms, a gymnasium and outdoor space.

The toxicants that would creep into classrooms and hallways predated Sky Valley’s move. The lights and caulking were infused with PCBs, an effective preservative popular in school construction before research revealed its toxicity in the 1970s.

Within three years of moving, decades-old fluorescent lights at Sky Valley started to fail, district records show. The fixtures smoked, caught fire and dripped sticky yellow oil.

Teachers began raising concerns. One teacher pieced together staff and student symptoms and raised suspicions about PCBs. In April 2014, Sky Valley Principal Karen Rosencrans emailed staff the first of many reassurances that the district had the problem under control.

“Our building is quirky and old and sometimes a challenge. But it is ours. And it is safe,” Rosencrans wrote, assuring parents that the district would remove and replace faulty lights. Rosencrans directed questions to the school district, which declined to comment on the contamination.

Two weeks later, a school district consultant carried out the first of at least half a dozen inspections conducted over the next seven years. It found elevated concentrations of PCBs in a science prep area near classrooms.

While the EPA does not set standards for indoor PCB concentrations, it offers “recommended” thresholds in schools that increase by age, aimed at reducing potential for harm. “They should not be interpreted nor applied as ‘bright line’ or ‘not-to-exceed’ criteria, but may be used to guide thoughtful evaluation of indoor air quality in schools,” the agency says of its recommended limits. In Sky Valley, the PCB levels exceeded the threshold for infants and toddlers.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has linked PCB exposure to impaired memory and learning ability, skin conditions, liver problems and other illnesses. Animal studies connect the chemical to thyroid and hormone problems, neurological damage and some cancers, depending on the number, length and dose of the exposures.

It’s difficult to tell exactly what levels of PCB exposures pose immediate harms, but growing research on the toxicity of the chemical has shown stronger ties to illnesses, said Keri Hornbuckle, director of the University of Iowa’s Superfund Research Program, an academic leader in studying airborne PCBs. “It only gets worse year after year.”

Some states enforce limits on indoor PCB concentrations, including Vermont and Massachusetts. Washington does not.

Later that year, the school district’s consultant, Seattle-based EHSI, returned to Sky Valley, this time looking for other hazards. It said complaints of headaches, sinus issues and sneezing among teachers and students were likely due to ventilation problems, which led to a buildup of pollutants. The inspection wasn’t focused on PCBs, but it found high carbon dioxide levels and some mold on campus, and the consultant recommended improving ventilation and removing carpets that can absorb toxic substances.

Over the course of a year, the school district removed 67 light fixtures suspected to contain PCBs, cleaned more than 100 other lights and removed some carpets from classrooms, district reports said. It later estimated it spent at least $1.6 million cleaning up Sky Valley, including money for testing, new lights and custodial services.

Rosencrans and Monroe schools’ operations director, John Mannix, sent a letter to teachers and parents in late 2015 assuring them that all areas were cleaned and treated according to EPA guidelines. Mannix, who now works at Mukilteo schools, did not respond to an interview request.

But that wasn’t the opinion of the Snohomish Health District, which raised red flags just two weeks later.

“Our concern is that PCB ballasts might have been missed when this issue was addressed last year,” wrote Snohomish health inspector Amanda Zych, according to records obtained by the Times. Among her observations: One classroom carpet suspected to have absorbed PCB oil was duct-taped down instead of taken out.

The district removed the duct-taped carpet and commissioned more air samples. This time the PCB concentrations were higher than in earlier tests, district records show.

Parents flooded the Snohomish Health District with dozens of complaints, records show. Kids reported headaches, breathing problems and thyroid and hormonal issues. Parents, students and teachers say they developed cysts and mouth sores; their skin cracked, peeled and changed pigment.

As the health crisis at Sky Valley was playing out, the EPA’s regional office found “several cities in Washington that we think would be a good place to look for PCBs in school lighting ballasts,” including Monroe, an official wrote in an email relating to a planned program to proactively examine schools for PCBs.

It’s likely the chemical is seeping into old campuses across the country without public knowledge, Hornbuckle said. “It’s not whether [PCBs] are there or whether they are toxic. We know they’re there and we know they’re harmful. The question is what do we do to address it.”

But without a requirement to test for PCBs in schools — and no requirement to disclose results if tests are performed — there’s no way to know how many campuses might have harmful PCBs in the air.

“The Smoking Gun”

By 2016, two years into the unfolding crisis at Sky Valley, administrators were giving regular updates to families reassuring them that the campus was safe.

Behind the scenes, emails show apparent dysfunction among school, health and environmental officials about how to tackle the problem. The Snohomish Health District looped in the state health and ecology departments, eventually triggering direct EPA involvement.

That February, an official from the state health department told other agencies that she didn’t think further air sampling at Sky Valley was necessary, records show. She suggested “a thorough wipe down of hard surfaces with warm soapy water and a thorough vacuum.”

A state toxicologist forwarded the email to an EPA official in charge of PCB remediation in the Pacific Northwest, writing, “Have you been looped into this? I’m not sure soapy water is the answer.”

It is not, according to EPA rules, which outline specific solvents needed to clean PCBs. The agency also recommends, but doesn’t require, removing all PCB-containing fixtures.

It’s unclear what it would cost to remove contaminated light fixtures from Washington’s public schools because the state doesn’t know the extent of the problem, a 2015 state Department of Ecology report says. In New York City, officials estimated a decade ago that it would cost about $708 million to clear PCB-laden lights from 772 schools built before 1979.

After the interagency email exchange, the EPA’s regional office stepped in to direct Sky Valley’s cleanup effort. “We’re anxious to understand the state of PCBs in the school,” Michelle Mullin, who oversees the EPA’s regional PCB program, wrote in late February 2016.

The EPA soon inspected the school, finding PCBs in several light fixtures, according to federal environmental records.

On April 21, 2016, the EPA talked with Monroe School District officials about its findings, recommending additional cleanup steps, records show.

Just hours later, as day faded into evening, nearly 100 parents filed into rows of folding chairs that lined the gymnasium at Frank Wagner Elementary School, a newer campus down the street from Sky Valley.

Speaking to the crowd, school officials emphasized that PCB levels weren’t high enough to exceed the EPA’s guidelines, according to The Monroe Monitor. Rosencrans, the Sky Valley principal, noted that some teachers had gotten so sick that they couldn’t return to campus, but others were in good health.

Deep cleaning was underway to address the campus’s environmental problems, school officials told the parents.

But parents — who confronted officials for the next three and a half hours — feared that regulatory standards weren’t enough to keep children safe.

“I just want to assert the fact that there might not be the science behind combining slightly elevated PCB levels, slightly elevated asbestos levels, slightly elevated radon levels, but when you combine all of those, we are the smoking gun,” said Shelby Keyser, whose children experienced some symptoms. “My kids are the smoking gun.”

She turned to other parents and asked them to raise a hand if their children, too, were a “smoking gun” example, The Monroe Monitor reported. The majority of the parents in the room raised their hands.

Still Not Cleaned

Six weeks after the tense town hall, the EPA found that PCB levels rose after cleanup, reaching the highest concentrations yet, according to an agency memo. These levels put anyone up to age 19 at risk, based on recommended thresholds.

Parents grew more desperate. Their complaints were not prompting aggressive action, so they turned to social media, forming a Healthy Sky Valley Advocacy Group on Facebook, with daily or weekly posts encouraging parents to report illnesses and sharing articles about PCB exposure.

A Change.org petition calling for the school district to relocate Sky Valley students was signed by 568 people and listed names of friends and family who had fallen ill at Sky Valley.

Some parents reluctantly pulled their children from the program. Teachers quit or sought reassignments or filed workers’ compensation claims, although the district would not say how many staffers left Sky Valley during this time frame.

“We really tried everything,” one mother told The Seattle Times. She withdrew her children from the school after they experienced severe health complications, including cognitive problems and early puberty. She requested anonymity for her children’s privacy. “We tried to get the school district to listen. We tried to get the health district to listen. We did all of this stuff and still nobody would listen.”

In fall 2017, the EPA delivered a clean bill of health to Sky Valley after district officials certified in writing that all PCB-containing light fixtures had been removed and that a litany of problems had been resolved, completing a multipoint plan the district had penned at the EPA’s request.

But that wasn’t the case.

Contrary to what Monroe School District reported to the EPA — and to parents — federal inspectors in October 2019 found PCBs in “multiple” light fixtures and in an air filter, discovered that classroom carpet that had been previously flagged hadn’t been fully removed, and raised concerns about PCB-laden caulk in the walls, EPA documents show.

They raised the same problems a year later.

“We are very concerned that PCB contaminated fixtures continue to be found, six years into the process of inspecting and taking inventory, cleaning and removing and disposing of light fixtures,” the EPA wrote in November 2020. “The EPA recommends [Sky Valley] address these concerns with more urgency than has yet been demonstrated.”

The EPA can penalize the district and school, the letter reads. That would be a rare step for the agency, and Bill Dunbar, a regional EPA spokesperson, would not comment on whether it plans to fine the district.

Last year, Monroe School officials again committed to addressing lingering problems, submitting a plan to the EPA. That plan still “did not fully meet our expectations,” so the EPA offered guidance, Dunbar said.

Removing PCB-laden light fixtures is a “no-brainer,” said Hornbuckle, the director of Iowa’s Superfund Research Program. While it wouldn’t completely clear the campus of PCBs, it would likely mitigate one of the highest exposure risks.

“Removing those PCB ballasts is something the state should be doing,” she said, adding that replacing outdated fixtures with energy-efficient lights has saved other schools money.

For some Sky Valley families, the consequences of the delayed action were devastating.

“This Stuff Is Everywhere”

In a King County courtroom last summer, Sky Valley teachers described their deteriorating health to a jury. Experts testified about the scientific links between PCBs and brain damage.

Convinced of the connection, a jury awarded three teachers, including Leahy, $185 million for exposure to PCBs at Sky Valley. Four months later, eight parents, teachers and students won a collective $62 million jury award against Monsanto, the chemical manufacturer of PCBs.

The litigation has resulted in one of the largest awards nationwide for individual PCB exposures. The Sky Valley verdicts include punitive damages, which are allowed under state law in Missouri, where Monsanto was headquartered.

In all, more than 200 parents and teachers have sued, claiming brain damage from exposure to PCBs. At least 17 other lawsuits are awaiting trial.

The complaints catalog many illnesses, but the lawsuits focus on linking cognitive problems to PCB exposure. It’s difficult to link illnesses to specific chemical exposures without more scientific research into their effects.

Bayer Pharmaceuticals, which in 2018 acquired chemical giant Monsanto, denied the allegations both in the lawsuit and in a statement. The company plans to appeal the jury verdicts.

Many parents, teachers and students with pending lawsuits declined to speak to The Seattle Times.

Leahy, now retired, said she doesn’t expect to collect her share of the $185 million jury award. “But it was never about the money. It was the only way to get the public to listen.”

The PCB exposure impaired Leahy’s memory and brain function. She couldn’t stand in a Sky Valley classroom without having headaches, dizziness and breathing problems, she said.

Others testified in court that their children developed depression and suicidal tendencies.

Cheryl Tye Pritchett, a mother who joined her children on campus multiple times a week until late 2016, testified in court that she developed a persistent cough, stomachaches and eventually fogginess and memory issues.

“I’m afraid to find out how severely damaged I am,” Tye Pritchett told a jury. Her children also got sick, she said.

Leahy’s attorney, Rick Friedman, whose firm represents all the Sky Valley plaintiffs, said the lawsuits point to a larger problem, which may be unfolding in schools across the state and nation.

“It’s kind of like lead paint in schools from a decade ago,” Friedman said. “How long until we realize that this stuff is everywhere?”

Pollet, the state lawmaker, said after learning about the Sky Valley saga from The Times that he intends to raise PCB concerns with fellow lawmakers this legislative session.

But he expects school districts to argue, as with lead testing, that remediation of PCBs would be financially devastating.

In 2020, Washington became the first state to successfully sue Monsanto over PCBs, in a lawsuit focused on the chemical in waterways. The chemical giant settled for $95 million, nearly $60 million of which went to the state’s general fund, where the Legislature can direct it to remediation of waterways — or other exposure points, including schools.

“Not Enforceable by Law”

The Sky Valley litigation originally took aim at the Monroe School District and Snohomish Health District, accusing the agencies of negligence for the slowly unfolding crisis at Sky Valley.

But King County Superior Court Judge Theresa Doyle dismissed the health district from the lawsuit after the district argued that loosely written state laws do not require enforcement or action when health inspectors find hazards at schools.

Heather Thomas, a spokesperson for the Snohomish Health District, said in an email that “a general duty by a public agency to inspect schools is just that — a duty to the general public only, and it does not result in a specific duty to enforce in this instance.”

Monroe School District also pointed to an absence in state and federal law of any requirement to remove PCB-laden material. It argued in court documents that it complied with EPA guidelines, and PCB light removal can take “5-10 years.” State and federal environmental agencies recommend removing lights before they leak, but these “recommendations are not enforceable by law,” reads the district’s report defending its actions at Sky Valley.

The school district, in declining interview requests, cited a sealed settlement proposal with Sky Valley teachers, parents and students that has not yet been finalized.

The district told the Times in July — after the first jury award — that the school has been cleared of PCB material.

But an EPA spokesperson said the agency is waiting on Monroe School District to submit a cleanup plan before it can make a “formal decision,” which could include another inspection, giving the school an all-clear, or issuing fines.

Meanwhile, at the state level, environmental officials, who flagged PCBs in schools as a research priority as early as 2015, are just now building a database of potential PCB hot spots after being delayed by a legislative appropriation.

The department only started surveying school districts last summer, beginning in Eastern Washington. The results of the survey should help the state know whether Sky Valley is an outlier or a bellwether.

“How many kids are sitting in classrooms exposed to PCBs and they don’t even know it,” Leahy said. “How could they know? It doesn’t hit you immediately. It’s like a slow death. You just get sicker and sicker and sicker until it’s too late.”

Jan. 23, 2022: This story originally misidentified the judge who dismissed the Snohomish Health District from a lawsuit. It was King County Superior Court Judge Theresa Doyle, not Douglass North.

Taylor Blatchford of The Seattle Times contributed reporting.