When Josh Tate was sentenced in 2017 to 10 years in prison for getting caught with drugs multiple times, his wife, Claire Tate, tried not to dwell on the moments he would miss with their two young kids. She didn’t see the purpose in sending Josh — who had struggled with a meth addiction for years but never been convicted of a violent crime — away for so long.

“You can’t punish a drug addiction out of somebody,” Claire Tate said recently.

Last year, state legislation supported by prominent conservative groups seemed to offer Josh Tate a chance to serve a larger portion of his sentence at home after completing education and self-help programs.

Claire and Josh began making plans, big and small, for once he was out of prison: going to a grocery store, visiting a hot dog stand in a small southern Arizona town, taking the kids to the beach.

One man had the power to delay their early reunion: Steve Twist. Twist has never held elected office. But over four decades the Arizona victims’ rights advocate, adjunct law professor and former assistant state attorney general has had an enduring impact on policies that created one of the nation’s most punitive state criminal justice systems.

As he had done several times before, Twist worked to torpedo the early release bill, meeting with lawmakers and sharing a list of concerns, including fears that people convicted of certain violent crimes would qualify for release.

Across the country, states both liberal and conservative have taken steps to reduce their prison populations. Similar efforts in Arizona have been incremental. The state established mandatory minimums for people who commit multiple and violent crimes; combined with a law that requires almost every prisoner to serve 85% of their sentence in prison — with the exception of people, like Josh, convicted of drug possession, who still serve 70% — this makes Arizona’s criminal justice system one of the harshest in the nation. Locking up so many for so long comes at a high price: Only four states spend a bigger share of their budgets on corrections.

Organizations and lawmakers attempting to change the state’s sentencing laws have blamed their failure on the tight grip Twist and his allies hold on criminal justice policy in Arizona.

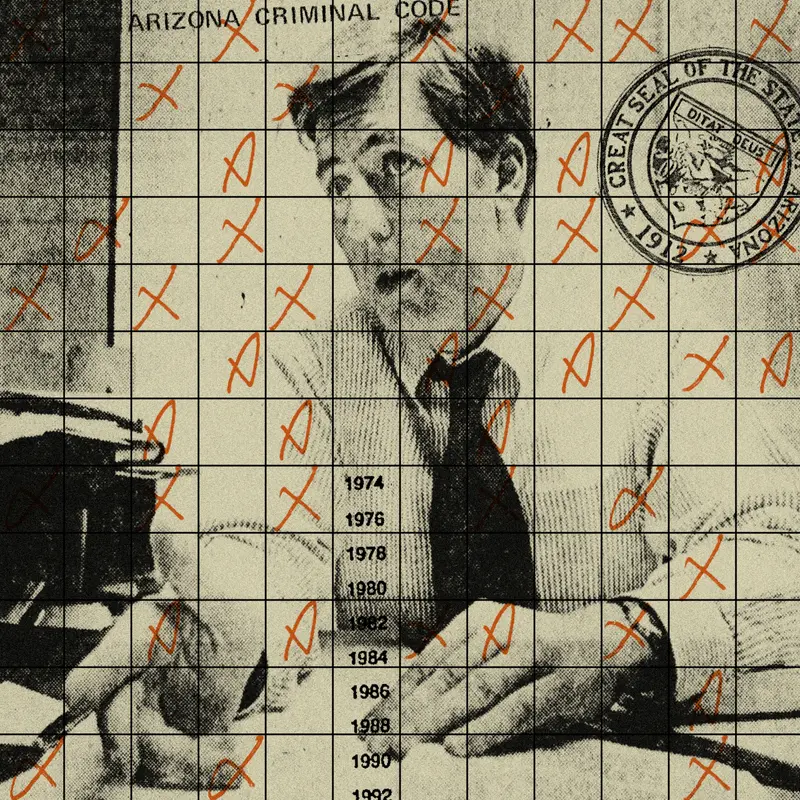

In the 1970s, first as a lobbyist for Arizona police chiefs, then as a lawyer for the Arizona Legislature, Twist helped rewrite the state’s criminal code to make sentencing more punitive. Later, as an assistant state attorney general in the 1980s, he continued to push for harsher laws that kept people in prison even longer. In the 1990s, working for the National Rifle Association, he helped enact similar policies in other states, including requirements that people serve at least 85% of their sentenced time, imposing life sentences after a third conviction for a violent felony, enforcing the death penalty and allowing young people to be charged as adults.

In more recent years, those who have worked with Twist and observed him closely said he remains a gatekeeper for criminal justice policies in Arizona. This continuing influence comes not only from his past work but also his relationships with governors, lawmakers, state supreme court justices, county prosecutors and other victims’ rights advocates. When proposals threaten laws he helped enact, he draws on this network to pressure lawmakers to oppose reform legislation.

“So many people defer to him,” said Pat Nolan, founder of a criminal justice reform group at the American Conservative Union Foundation. “His influence is felt behind the scenes, it’s not out in the open.”

Those who have worked with Twist and observed him say it’s not clear what has driven his passion for criminal justice issues. He has said in previous interviews that his work as a prosecutor helped him understand “the plight of crime victims in our system.” And when Twist opposes changes to sentencing laws, he usually references crime victims. This work has made him a nationally recognized figure in the victims’ rights movement, including being honored by the Department of Justice in 2020 with a Victims’ Rights Legend Award. And it’s given him stature in Arizona’s political establishment.

Paul Cassell, a University of Utah law professor who wrote a textbook with Twist about crime victim law, said he doesn’t know of a personal experience that shaped Twist’s views. “I think Steve just thinks it’s the right thing to do,” he said.

Heather Grossman, a domestic violence survivor who was shot in the neck in 1997, leaving her paralyzed from the neck down, said that Twist has been a “lifesaver” for her and her family. Twist has connected Grossman to resources, mentored her son, and helped when her insurer refused to cover her 24-hour nursing care.

“He’s such a good person, and I can only think he works for the best kind of justice,” she said. “He’s one of the best people I know.”

Twist did not respond to ProPublica’s repeated requests to be interviewed or to comment for this story.

Twist and his allies have claimed that Arizona’s sentencing laws reduced crime, even as evidence mounts that such policies are not only inhumane and costly, but also ineffective.

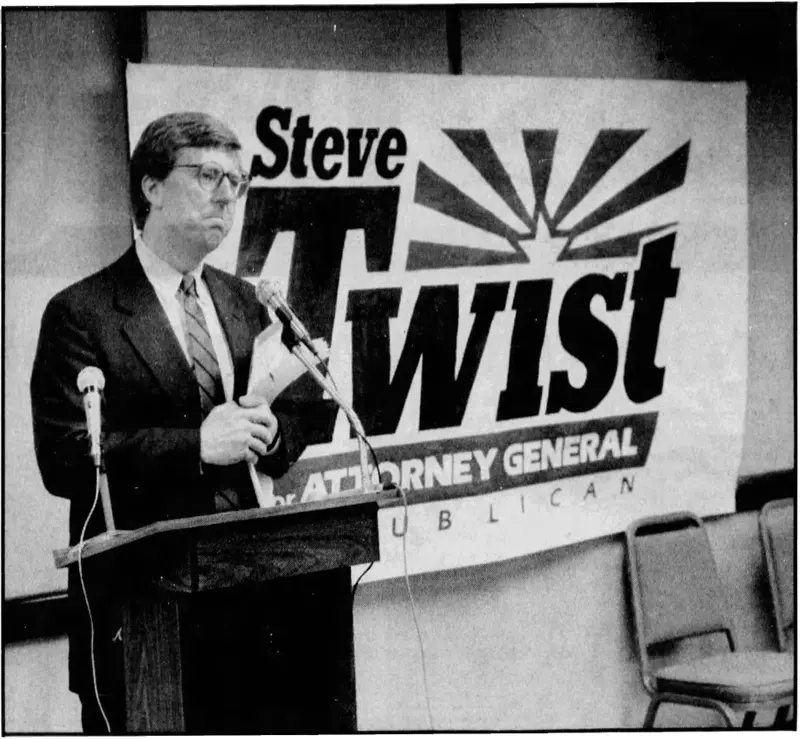

Grant Woods, who died last year, defeated Twist in the 1990 Republican primary for Arizona attorney general. In a 2021 interview with ProPublica, Woods described the candidate he faced as someone who he believed had “decided very early in his life that the best way to provide public safety is to figure out who is committing crimes and to lock them up as long as you can. And I don’t think he’s really changed much since then.”

After the Republican-controlled Arizona House of Representatives passed its early release bill in February 2021 with overwhelming support, Claire Tate began unpacking her husband’s clothes from a storage unit and telling friends at church that he would be home soon.

Later in the legislative session, rumors began to spread among lawmakers that a revised version of the bill would lead to the release of child sex traffickers, which lobbyists for the bill said was untrue. Efforts to debunk the rumors failed, and the Legislature adjourned without taking final action. Josh remains locked up.

For some, including the bill’s Republican lead sponsor, state Rep. Walt Blackman, its failure was the latest example of Twist defeating any proposal that would dismantle laws he helped shape.

“All lines go to him,” Blackman said.

“Leading a Charge to Lock Offenders Up and Throw Away the Keys”

Twist graduated from law school in 1974, as much of the nation was beginning to panic over rising crime. That year, the rate of serious crime — murder, rape, robbery, aggravated assault, burglary, larceny and auto theft — jumped 17%, the largest increase in the 44 years that the Federal Bureau of Investigation had collected statistics.

In a special address to Congress in June 1975, President Gerald Ford urged lawmakers to enact measures to control crime.

That year, a commission was at work revising Arizona’s criminal code, which dated to its territorial days. A Tucson Citizen editorial called the old laws “outdated, ambiguous and ineffective.”

Twist got a job as a lobbyist for the Arizona League of Cities and Towns who represented the Arizona Police Chiefs Association. He left that job to work for the Arizona House of Representatives, where, as he described it, he became a “principal drafter” of the new criminal code as it was debated by lawmakers.

The code was rewritten in modern language; some anachronisms, such as rules regarding dueling, were deleted. But more importantly, the code’s purpose was reframed: Sentencing should have a “deterrent influence,” it stated. The new laws also limited judges’ discretion by imposing mandatory prison time for repeated felonies and violent crimes.

“Without Steve this couldn’t be done,” the chair of the House Judiciary Committee told a reporter at the time.

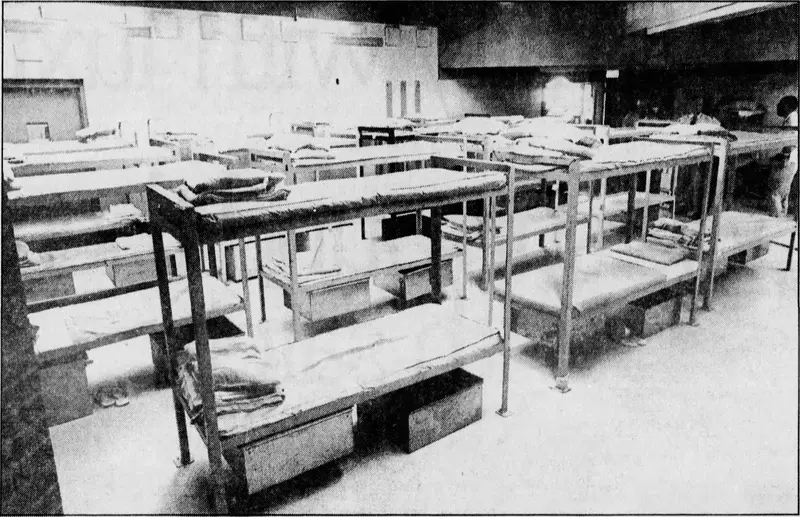

In 1978, months before the code was to go into effect, a South Carolina consulting firm hired by the Department of Corrections to develop a plan to ease prison overcrowding released a report critical of the new laws. The report’s author, Stephen Carter, predicted they would contribute to a prison population increase from about 3,000 to at least 10,000 over a decade.

By January 1988, the prison population had exceeded those projections, with more than 11,000 people incarcerated across the state. Arizona had run out of space in its prisons and was housing prisoners in tents, warehouses and trailers.

Twist changed jobs again in 1989, becoming chief assistant to then-Attorney General Bob Corbin, a job in which he continued to be a fixture at the Legislature.

Chris Herstam, who served as a state representative for eight years starting in 1983, recalled seeing Twist and others from the attorney general’s office huddled for hours in the House Judiciary Committee chair’s office. “They were leading a charge to lock offenders up and throw away the keys,” Herstam said. “They were very much into victims’ rights in an attempt to reduce crime dramatically and put the bad guys in jail, period. That was their mission.”

As Twist began working with victims of crime, his interest in their issues deepened. He wrote Arizona’s Victims’ Bill of Rights, a constitutional amendment passed by voters in 1990 that guarantees crime victims certain rights, including the right to be informed of criminal proceedings and to be present in the courtroom.

However, resistance to the massive increase in incarceration was building. In 1992, a criminal justice research group released a study that concluded the rewritten criminal code’s broad descriptions of crimes and narrow sentencing provisions had gone too far in shifting power from judges to prosecutors. The report’s authors recommended eliminating mandatory minimums and returning to sentencing ranges that would allow judges to decide an appropriate punishment.

“It shows what was a sincere effort at achieving harmony in sentencing,” wrote the report’s author, Kay Knapp, was “instead producing anarchy.” Knapp was a former U.S. Sentencing Commission director.

The Arizona Prosecuting Attorneys’ Advisory Council attempted to refute Knapp’s findings with a report of their own. Authored by Michael Block, a professor of economics and law at the University of Arizona, the report argued that getting tough works and that Knapp’s report was unbalanced. Block, who would later co-found the BASIS charter schools chain, told a joint legislative committee that punishment in Arizona was in line with the rest of the nation.

That year, the committee recommended rehabilitation be added as a purpose of the criminal code. The panel also proposed restoring judges’ ability to adjust sentences.

Those recommendations were ignored. Instead, Gov. Fife Symington proposed ending parole in Arizona and replacing it with “truth in sentencing,” which would require people in prison to serve a minimum of 85% of their sentences. Lawmakers passed the measure in 1993.

At the time, a new NRA program called CrimeStrike said it had helped Arizona officials enact the harsher penalties.

CrimeStrike’s director: Steve Twist.

A National Platform

In the 1990s, CrimeStrike bought full-page ads in magazines and newspapers touting its mission to “put real justice back in our criminal justice system.” Not only was crime a threat to personal safety, the pitch went, it was also “the greatest threat to your Second Amendment right to own a gun. It is their violent misuse of firearms that makes your firearms the target for gun-ban groups, anti-gun politicians and the media.”

At the 1994 Conservative Political Action Conference, Gary Kreep, then the executive director of the U.S. Justice Foundation, a conservative legal issues organization, introduced Twist as CrimeStrike’s director and the person who had recently helped craft “precedent-setting” legislation to abolish parole in Arizona.

When Twist took the stage, he issued a rallying cry to the CPAC crowd: “We simply cannot give speeches about this any longer. We have to become an army, a coalition across America to tell politicians that the time for reform and change and getting tough is now, because getting tough works.”

Twist had a national platform to spread the ideas he had developed in Arizona.

CrimeStrike claimed it helped pass “truth-in-sentencing” laws in Mississippi and Virginia, and worked on “three strikes and you’re out” laws in California, Delaware, Georgia, North Carolina, Pennsylvania, Vermont and Washington. In Texas in 1993 and Mississippi in 1994, the group pushed for billion-dollar bonds to build new prisons, according to media reports. CrimeStrike volunteers “publicize the records of judges and politicians whom they see as being soft on criminals,” the Houston Chronicle reported. The group also advocated for constitutional amendments for crime victims like the one passed in Arizona.

Other opportunities for Twist to influence criminal justice policy across the country followed.

The 1994 Crime Bill passed by Congress and signed into law by Bill Clinton provided grants for building and expanding prisons to states that required prisoners convicted of violent crimes to serve 85% of their sentence. That year, Twist teamed up with Block, the University of Arizona professor, to co-author the “Report Card on Crime and Punishment,” which they claimed was “the first comprehensive historical review ever accomplished of crime and punishment in the states.” The report was done for the American Legislative Exchange Council, a corporate-funded group that brings together conservative state lawmakers and representatives of corporations to develop and disseminate copycat legislation.

(ALEC has since changed course on criminal justice policy, including publicly supporting the proposed 2021 Arizona sentencing reforms that Twist opposed.)

The 1994 report card cited federal crime and imprisonment data from 1960 to 1992 to argue that six of the states with the largest increases in incarceration rates for violent crime were also among the states with the biggest declines in violent crime. “The message here is unequivocal. Leniency is associated with higher crime rates; getting tough brings crime rates down,” the report stated.

Experts dismissed Twist and Block’s methods and conclusions. Alvin J. Bronstein, the founder and then-director of the American Civil Liberties Union’s National Prison Project, called it “voodoo criminology.”

Marc Mauer, former executive director of The Sentencing Project, a D.C.-based group opposed to mass incarceration, said the report — which received media coverage nationwide — influenced conservative lawmakers by “doing their homework for them,” providing a “research-based” report to support model legislation they could introduce in their home states.

Mauer said there was no direct link between the rising imprisonment and declining crime rates Twist cited as proof that his approach was working. Mauer said that it was misleading to compare the crime rise from 1960 to 1980 with the decline from 1980 to 1992. Mauer said that crime reporting in 1960 was “very sketchy” in many places, and many crimes weren’t reported to police. By 1980, reporting had improved.

“Any serious scholar would have to say there was an increase, but we can’t be sure of the scale of the increase, because we don’t know how many crimes were not reported back then,” he said.

And studies that followed would find no strong connection between longer sentences and crime rates.

A 2004 report by the American Bar Association criticized mandatory minimum sentencing, noting the sharp increase in the time people were serving in prison: Between 1980 and 1992 those imprisoned served an average of 18 months, while from 1992 to 2000 it jumped to an average of five years. The report noted the harm done to minority communities by widespread incarceration and urged lawmakers to find alternatives.

In 2012, a Pew Center on the States study found that for a substantial number of people in prison, there is “little or no evidence” that longer sentences prevent crime. And in 2014 the National Research Council concluded that the increase in incarceration might have reduced crime, but the magnitude was uncertain. The research council said that policymakers should reconsider their sentencing policies because of the “social, financial and human costs.”

Virginia Mireles, who has been in and out of Arizona prisons five times since 1996, said the threat of longer sentences didn’t deter her from stealing to feed her drug addiction.

The name of the judge who handed down Mireles’ first sentence will forever be imprinted in her mind: Judge Deborah Bernini sent her to prison for a year for possession of $10 worth of heroin.

But prison didn’t offer anything to treat her addiction. Mireles continued using heroin when she wasn’t incarcerated, saying that at one point she felt her only purpose in life was to be a “dope fiend.” The most recent time she was arrested, in 2013, she had stolen $27 from a neighbor’s wallet while he was in the shower.

“I needed gas, I needed my fix,” she said. “And I needed lunch money for my kid.”

When police showed up at her Tucson apartment, she admitted stealing the money, but said she intended to repay her neighbor when she got paid at midnight. Still, Mireles was charged with second-degree burglary and sentenced to six-and-a-half years. While she was incarcerated, the prison’s addiction programs had long waitlists so she read self-help books instead .

Two of her three children have since had contact with the criminal justice system. Her son has been in prison and her daughter was recently released from jail.

“So what are we keeping people safe from? You’re not just sentencing that person, it’s their family as well,” said Mireles, who has now stayed away from heroin for nine years and, in her free time, volunteers in the community and advocates for criminal justice reform.

Repeating Arguments From the 1990s

Twist has continued to use the same arguments he’s used since the 1990s to defend his ideas despite mounting evidence debunking them.

In 2019, Twist addressed the Arizona Criminal Justice Commission as it evaluated how to best collect and analyze data on the state’s criminal justice system.

Twist distributed to the commission a chart showing the state’s prison population and crime rate from 1974 to 2017. Overall, as the prison population rises, the crime rate declines. It echoed the fundamental argument of his 1994 “Report Card on Crime and Punishment”: Increasing incarceration reduces crime.

“For those people who say that our current system hasn’t resulted in more public safety, I urge them just to consider the chart,” Twist said. He pointed out that the correlation is not causation, but said the chart shows a “powerful social correlation,” as the prison population has increased while the crime rate decreased.

“But these are more than numbers. These are tens of thousands of our fellow citizens who were not harmed by crime,” he said.

Donna Hamm, founder of Middle Ground Prison Reform, an Arizona prisoner advocacy group, was present at the meeting as Twist credited lengthy sentences for the decline in crime. Twist’s arguments that truth in sentencing is effective “clash with reality,” she said, but commission members — mostly police or prosecutors — nodded in agreement as they listened to the person Hamm calls the “godfather of the sentencing code in Arizona.”

“You have to sit on your hands and listen to him say those things,” Hamm said of Twist.

“But it’s almost worse that there’s no formal questioning or even challenging. It’s like no one is even looking at the charts.” Hamm continued: “These are the people in control. These are the decision makers. These are the influencers.”

“The Invisible Hand of Steve Twist”

Those who have challenged Twist’s ideas come to learn of his role as a gatekeeper over criminal justice policies in Arizona.

In 2011 and 2012, then-state Rep. Cecil Ash introduced 17 bills related to the criminal justice system, including legislation to relax mandatory sentencing and to give people in prison a chance to earn early release for good behavior. Ash, a former Maricopa County public defender, said he had seen his clients accept plea agreements rather than go to trial solely because of the long sentences they would face if they lost in court.

He said he was told by other lawmakers, “That’s been done before, you know, you’ll never get anywhere,” and that a fellow Republican lawmaker cautioned him privately that it “wasn’t healthy” to advocate for criminal justice reform.

None of the bills passed.

Ash said that Twist didn’t openly oppose his proposed reforms. He didn’t have to. Twist instead relied on a network of connections built over decades to do the work.

“From the very beginning,” Maricopa County Attorney Bill Montgomery and Yavapai County Attorney Sheila Polk opposed Ash’s efforts, the former lawmaker said. Both are longtime Twist allies. Polk said Twist hired her in the Arizona Attorney General’s Office, and she considers Twist a personal friend. Montgomery, now a state Supreme Court justice, has described Twist as a mentor and his best friend.

Polk described Twist as a “very thoughtful, balanced individual” and said they discuss legislation with each other. She said they both favor diversion programs that allow people to complete treatment and reentry programs that help formerly incarcerated people integrate back into society. (Montgomery said as a sitting justice it would be inappropriate for him to comment.)

Twist has other powerful connections. His son, J.P. Twist, ran Doug Ducey’s successful campaigns for governor, and is political director for the Republican Governors Association. His wife, Shawn Cox, is head of victim services at the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office and serves on the county’s commission that recommends candidates for appointment as trial court judges. Steve Twist co-founded the Goldwater Institute, a conservative public policy and advocacy group that is active at the Arizona Legislature, as well as Arizona Voice for Crime Victims, a nonprofit that provides free legal representation to crime victims.

The Legislature in 2014 added a $2 fee to fines levied by the state’s Game and Fish Department and directed the money to nonprofit groups that work with crime victims. At the time, the Arizona Capitol Times noted Arizona Voice for Crime Victims would be the only beneficiary. The nonprofit has since received nearly $4 million from the fund, records show.

In a recent court filing, defense attorneys raised questions about the relationship between Arizona Voice for Crime Victims and the Maricopa County Attorney’s Office, alleging a conflict of interest. In a motion responding to the claim, the nonprofit called the attacks “unfounded.”

Cox, J.P. Twist and Arizona Voice for Crime Victims CEO Colleen Clase did not respond to requests for comment.

Democratic former state Rep. Diego Rodriguez said Twist’s network of allies gives him “more influence than any Republican legislator when it comes to sentencing reform.” Lawmakers listen to Twist because of his influence with the governor, he said.

“It’s not their communities that are being drained of resources,” Rodriguez said, referring to the disproportionate impact of incarceration on minority communities.

In 2021, Arizona had the nation’s highest rate of incarceration for Latino people, according to The Sentencing Project. It ranked fifth for Black imprisonment.

Emails obtained through a public record request show Twist’s influence in the office of the governor. In 2020, he was part of a group of business leaders on regular conference calls with Ducey to discuss the governor’s COVID-19 pandemic response. In late 2020, as the governor’s office prepared for an upcoming legislative session, Twist was asked to help develop the governor’s agenda. That month, Twist was invited to meet privately with Ducey. Recently, Twist signed on as campaign chair for Anni Foster, Ducey’s general counsel, who is running in a special election for Maricopa County attorney.

The governor’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

Caroline Isaacs, executive director of Just Communities Arizona, a group that works on public safety policies that don’t involve the prison system, said she repeatedly hit walls as she pursued sentencing reform at the Arizona Legislature. In 2020, Isaacs joined like-minded groups to pursue a citizens’ initiative to expand earned release credits and restore judicial discretion, among other things.

Twist opposed the measure. An op-ed he co-wrote with former U.S. Sen. Jon Kyl leaned on arguments Twist has made for decades: “Crime was skyrocketing during the 1960s and 1970s under the system to which the proponents want to return. But since the bipartisan reforms in 1978, crime rates have plummeted.”

Voters never got a chance to decide the measure. Then-Pima County Attorney Barbara LaWall and Heather Grossman, an advocate for victims of domestic violence, among others sued to challenge the petition signatures. The initiative was kicked off the ballot.

LaWall, known as a tough-on-crime Democrat during her 24 years as Pima County attorney, did not respond to a request for comment.

Grossman confirmed to ProPublica that Twist personally asked her to join the lawsuit. Twist has worked as an attorney for Grossman’s foundation for victims of domestic violence, Haven of Hope.

“That’s the invisible hand of Twist,” Isaacs said.

Maintaining the Status Quo

When Walt Blackman was elected to the Arizona House of Representatives, one of his priorities was to reform sentencing laws. A self-described “staunch” conservative Republican and man of faith, Blackman said he believes people convicted of nonviolent crimes should have a chance to redeem themselves.

Blackman kept hearing that if he wanted to pursue criminal justice reform, he should first meet with the “guru” on the subject, Steve Twist. It was clear Twist was considered a gatekeeper, he said.

“My first impression of Steve Twist was that he had an agenda. And his agenda didn’t line up with mine,” Blackman said. But, he noted, “he didn’t come out and say, ‘Don’t work on criminal justice reform.’”

During Blackman’s first session, in 2019, he introduced a bill that would ease the requirement that people serve 85% of their sentences, expanding credits for good behavior and participating in programs and treatment. The legislation didn’t receive a hearing.

In 2020, he introduced another version of the bill. That year it passed in the House unanimously but died when the session was cut short by the pandemic.

In 2021, Blackman was appointed chair of the House Judiciary Committee. During the committee hearing, conservative groups testified in support of the legislation. Boaz Witbeck, the state director for Americans for Prosperity, a conservative political action group, called the bill “common sense reform,” noting many states had gone much further to reduce sentences for nonviolent crimes.

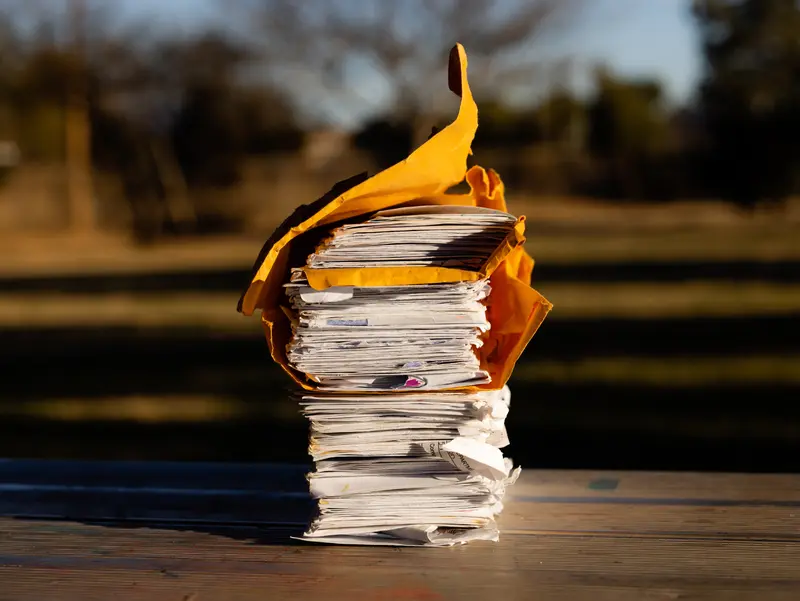

The House passed the bill in February of that year, around the time Twist was emailing senators about his concerns with the legislation.

In one letter, he said he was in favor of “meaningful criminal justice reform that does not compromise public safety, nor the rights of crime victims.” He claimed that crimes such as female genital mutilation and sex trafficking would receive reduced sentences under the bill.

Blackman said that Twist’s concerns were addressed in a scaled-back version of the bill that was resurrected in the House Appropriations Committee.

Twist didn’t appear satisfied with the results. The goal posts kept moving.

“When it looked like the bill had a chance to pass, that’s when he did a full on ‘poison pill,’” Blackman said.

The Maricopa County attorney testified in favor of the revised legislation. But then, a rumor began circulating, falsely claiming that the bill would allow the early release of child sex traffickers. The county attorney’s office emailed lawmakers attempting to debunk the rumor.

The bill died, and Blackman didn’t propose reforming sentencing during this year’s legislative session.

“Arizona is not ready for real criminal justice reform as long as Steve Twist is in Arizona,” Blackman said.

Claire Tate still follows efforts to reform Arizona’s criminal justice system, but now knows not to get her hopes up. Her life, she said, remains on hold. The kids got bikes for Christmas in 2020, but she hasn’t taught them to ride because she doesn’t want Josh to miss that milestone. Claire, who moved in 2019, sometimes walks into her kitchen and is struck with the thought that Josh has never been in that room.

Claire has tried to keep moving forward. When her eldest son, Elijah, wanted to wear a tie to church, Claire watched a YouTube video to learn how to tie it.

“This has all been just peppered with a lot of loss and a lot of pain,” she said.

Because the pandemic restricted visitation at Arizona prisons, Claire and her kids haven’t seen Josh in person for more than two years.

She has saved all of what she calls the “big” things. Someday, they’ll go to the beach, a petting zoo and see the redwoods. Josh will be out of prison next July.

Mollie Simon contributed research.