On the night of Sept. 1, Dhanush Reddy and his fiancee, Kavya Mandli, were returning home from a North Jersey mall when the remains of Hurricane Ida turned their drive perilous.

Rain pounded down, soaking the streets with so much water that cars stalled and police shut down traffic. They felt their own car rattling, and they abandoned it in a nearby lot. Deciding they’d walk to safer ground where Mandli’s brother could pick them up, they waded hand-in-hand into murky water “until we reached the middle point of the road,” Mandli recalled, “where it just sucked us both inside.”

They were both suddenly underwater, being pulled toward a large black vacuum that seemed to be guzzling anything and everything into its wide, open mouth. Mandli managed to grab part of a bridge railing, but Reddy clutched only her hand. She shouted for help as she tried to wrest her fiance from the vortex. But it was just too wet, too slippery. Reddy disappeared. Mandli was left holding his empty jacket.

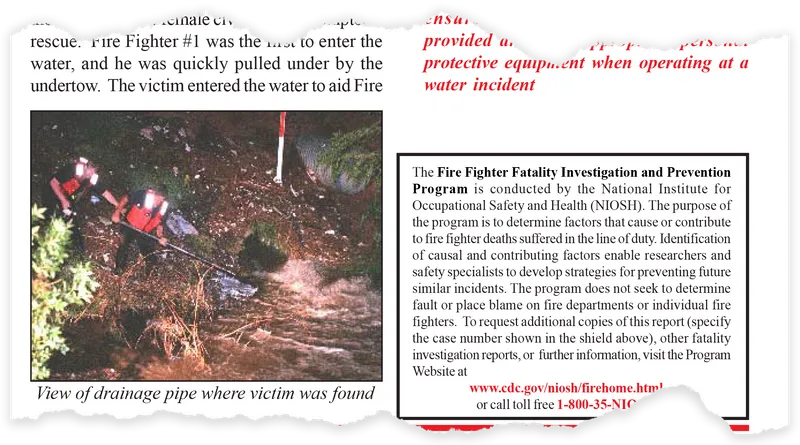

As South Plainfield police searched for Reddy, who had been sucked into a 3-foot-wide stormwater drainage pipe that ran underground, they looked where they thought it might spit him out, on the other side of the road. Mandli’s heart jumped when they told her they found a man hanging from a tree branch and calling for help.

But it was 18-year-old Kevin Rivera, who had also been pulled into a drainage pipe. “I was completely underwater,” he told ProPublica. “I couldn’t grab a grip to hold on to anything. I just covered my head with my arms and just sort of tried to ride it out till I came out on the other side or maybe got a little gasp of air.”

Reddy’s body was found the next day in a wooded area, blocks away from where he got pulled in. The engineer and construction project manager was dead at 31.

During the same storm, in the same state, three others died the same way.

There’s no official count of how many Americans get pulled into storm drains, pipes or culverts during flood events, but ProPublica identified 35 such cases since 2015 using news accounts and court records. Twenty-one of those people died; nearly half of those lost were children. Thirteen of the deaths happened in the past three years alone. The numbers are likely an undercount, since reports of flood deaths often don’t give details other than the fact that someone was swept away.

Despite records of horrific cases that span the country and stretch back decades — and the scientific consensus that climate change will only worsen flooding — federal, state and local government agencies have failed to take simple steps to prevent such tragedies from happening, ProPublica found, after more than a dozen interviews with government officials, engineers and weather experts, as well as a review of documents including death investigations, government meeting minutes and emails, and academic papers. Officials are not surveying the nation’s aging stormwater drainage systems, which are being taxed beyond capacity by record downpours, to flag openings that could pose a hazard and install grates to prevent people from being sucked in.

The National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, an arm of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, has recommended these steps, but it has no authority to compel cities or counties to act on that advice. It issued two reports on storm drain hazards after the near-identical deaths of firefighters during flood rescues. The first died in 2000. The second died in 2015. The first report did not reach the officials who could have prevented the second death.

ProPublica found instances in which local and state governments knew about a hazard but didn’t secure it. A man who died on the same night as Reddy, in Maplewood, New Jersey, was among a group of neighbors who had warned town and state officials that a storm pipe near their homes was dangerous; the man was pulled into the large opening while trying to clear out debris. That same night, in Passaic, New Jersey, two college students were sucked into the very same drain where, just one year earlier, a DoorDash driver had been pulled in. She had been dumped into a river and survived; they were expelled into the same river, but they died.

Some local and state government leaders have pushed back against recommendations to put in grates; they can be expensive to install, they trap debris and they can make flooding worse, opponents said. People can also become pinned to them and drown. But other municipal leaders and engineers said these problems can be overcome by using angled grates that provide victims an escape, and by investing in maintenance schedules so that covered drains don’t get clogged.

“It’s life or death,” said Ken MacKenzie, the executive director of Denver’s Mile High Flood District, who has for years tried to rally officials across the country to install grates and address the problem. He worked up his own count of deaths from 1996 to 2015, and he tallied at least 20 lives lost during that period. “It’s a hidden danger in nearly every community. And yes, it might cost a couple thousand dollars. But it’s worth it to not kill someone’s child in a culvert.”

Stormwater drainage is the type of infrastructure that people rarely think about until water is rushing down the road and cars are floating away. But when you walk around your neighborhood, you’ll see evidence of these systems all around you, from the small openings that run along curbs to larger pipes and culverts designed to channel rainwater into local waterways, retention ponds or stormwater treatment facilities. These systems are built to handle only so much water, and when the amount of rain exceeds the system’s capacity, it can lead to dangerous flooding in unexpected locations.

Many of these drainage systems were built decades ago and are designed based on historical rainfall data, which was used to help predict what capacity the systems should be able to handle. But Marouane Temimi, an associate professor at Stevens Institute of Technology who researches rainfall and flooding, said those predictions rely on one big assumption: “That the climate will continue to behave the same way it has been behaving for decades now,” he said. “If the climate changes — that’s what we are witnessing — then the past is no longer a good guide for the future.”

In the Northeast, for example, the amount of rainfall from heavy events increased by more than 70% from 1958 to 2010. Ida unleashed record-breaking rainfall on the region this year. So did the remnants of last year’s Hurricane Isaias, during which at least three good Samaritans were pulled into a culvert in Hockessin, Delaware, while trying to rescue a man trapped in his flooded car, and a 16-year-old boy in Bethlehem Township, Pennsylvania, watched a 6-year-old boy get sucked into a pipe and went in after him. They all survived.

The higher the floodwater, and the more of it that’s rushing toward a culvert or pipe in a maxed-out drainage system, the more dangerous the conditions can get. To get a sense of how much force can be in play at the entrance of these pipes, consider that every cubic foot of water weighs 62.4 pounds. So if someone is standing in 4 feet of water, that’s nearly 250 pounds of force. “And that's not including any velocity that's heading toward the pipe,” said MacKenzie, the Denver flood district director. “And so if you have a full-grown man at maybe 200 pounds, he’s up against 250 pounds of water pressure pushing into the inlet of that pipe.”

Rainfall has also increased in St. Louis in the past decade, said Jim Sieveking, a science and operations officer for the National Weather Service who’s based in the area. The city is particularly at risk for flooding because the Mississippi, Missouri and Illinois rivers converge around the same region, and urban sprawl and development have reduced the amount of permeable land that can absorb excess water. “We’ve seen our fair share of flooding in these past years,” he said.

On July 10 near St. Louis, Aaleya Carter and her family were on their way home after seeing the latest Fast and Furious movie. It was Aaleya’s birthday celebration. She had just turned 12.

There were heavy rains and thunderstorms that night as her aunt drove a small SUV along Interstate 70. The aunt spotted a flooded area in the road and turned around, but the wind and the slippery conditions made the car slide down an embankment toward a drainage culvert, which was filling with water.

Bridgette Carter, Aaleya’s mom, had to think and move quickly. Her three babies — including Skylar, 8, and Carter, 6 — were in the back seat, and water was starting to pour into the car. “My first instinct was to get out the car because the doors weren't opening,” Bridgette said.

It was a frantic rush to unbuckle all of the children and then climb out of the front driver’s side window, the only one that would open. While Bridgette was placing her two youngest on a roadway that was safely out of the water, Aaleya was clinging to the vehicle. “I was reaching for Leya,” the mother said. “And it swept her in the drain. The current was so strong.”

Aaleya, a goofy, funny kid who loved making TikTok videos and often helped her mom get dinner ready, was found a few hours later in a tree near a creek where the drainage pipe emptied. She had drowned.

Missouri’s Department of Transportation is responsible for the drain that Aaleya was pulled through. It was last updated in 1975. State officials wouldn’t say whether they have ever reviewed drains to determine if some should have safety measures like warning signs and grates. They pointed ProPublica to the Federal Highway Administration, which couldn’t name an instance when it had done such a safety evaluation, but noted that states have the autonomy to determine whether a grate is needed and to place flood warning and depth gauge signs at drains.

The loss of Aaleya was so unbearable that Bridgette decided to move her family to McKinney, Texas. “It’s hard,” she said in a conversation punctuated by tears. “It’s too much. … Everything just reminds me of my baby.”

The danger that large pipes and culverts pose to people during floods is not unknown to the federal government. NIOSH, the occupational safety arm of the CDC, issued a key recommendation two decades ago that could have saved lives. It came after a tragedy in Denver.

On Aug. 17, 2000, the city was drenched with up to 3 and a half inches of rain, causing flooding. Firefighter Robert Crump and his partner got an alert about a woman in distress. The water surrounding the woman appeared to be about waist deep. The firefighters didn’t know she was standing on the edge of a culvert near 10 feet of water. Crump’s partner, Will Roberts, jumped into the water to save the woman and was pulled under the surface by the drainage vacuum. Crump jumped in after his partner and was able to pull him to safety.

While his partner was trying to tie a cord to himself to attempt another rescue, Crump plunged back into the water to save the woman. He was pulled into the open drainage system that runs under the road. His body was found hours later, several blocks away from where he went missing.

NIOSH investigated Crump’s death and, in 2002, issued a report with recommendations for cities everywhere to prevent similar accidents, holding up as an example what it said Denver had done in the aftermath: covered the drainage pipe with a grate and then identified all similar open sewers, drains and culverts to start planning for more possible grates. (When contacted by ProPublica, Denver officials couldn’t find those records or say how much of that they wound up doing.)

Fifteen years after Crump died, another firefighter died after being pulled into an open drainage pipe during heavy rains, this time in Claremore, Oklahoma.

Jason Farley and his colleagues were wading through floodwater while trying to rescue people trapped in their homes when he stepped into a catch basin and was pulled into a drainage pipe. Another firefighter jumped in after him and was also pulled in. The other firefighter traveled almost 280 feet through the pipe and was expelled into a creek. Farley got tangled up in the pipe and drowned.

NIOSH once again released an investigative report, with recommendations that echoed those it had issued after Crump’s death: Government agencies should consider requirements for “identifying, marking, and guarding underground storm drains,” the report said. Sean Douglas, chief of the Claremore Fire Department, had requested that NIOSH investigate Farley’s death. He said he sees NIOSH reports from time to time in trade journals and firefighter magazines, but that he hadn’t seen the Denver report or its recommendations. “They’re not really in front of everybody all the time,” he said of the reports. “A lot of fire departments may not even talk to other fire departments, let alone an appendage of the CDC.”

A spokesperson with NIOSH said they post the reports on their website and send them out to 79,000 announcement and newsletter subscribers. The spokesperson also said that the group’s investigations have contributed to important safety improvements for firefighters. But fire agencies aren’t responsible for the stormwater drainage reforms that NIOSH proposed; city and county public works managers usually are. ProPublica could identify no federal agency set up to inform local officials directly of these safety hazards and recommendations.

At the spot where Farley died, Claremore put up guardrails but opted against a grate, out of a concern that people would get pinned against it during a flood, but also because it would need extra maintenance to keep it free from debris that could stop water from flowing in. Douglas said the city has identified areas prone to flooding, cleared out debris before and after storms, raised awareness of the hazards through signs and instituted road closures in problem areas. He said he continues to work with the city to install more markings of the open drains and where they may lead, and Garrett Ball, the city’s engineer, said Claremore began mapping its storm drain system, an effort he hopes will be completed in the next year or two.

A few communities have aggressively tackled storm drain safety in reforms that followed tragedy. Bolingbrook, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago, reviewed more than 40 storm drain inlets and grated some of them after a 6-year-old boy was pulled into one and drowned in 1998; the community also settled a lawsuit with the boy’s family for $2.8 million.

And Cedar Rapids, Iowa, evaluated 18 inlets and decided to place grates at 15 sites, some of which were large culverts.

The city embarked on the improvements after Logan Blake, 17, was swept into a culvert in 2014 when he went after a Frisbee during heavy rains. Logan’s friend jumped in the water to attempt to save him and was also pulled into the drain. The two teenagers traveled more than a mile and a half through the drainage pipe before being dumped into Cedar Lake. Logan’s friend survived and was able to walk to a nearby hospital. Logan’s body was found about 19 hours later.

Instead of suing, the teen’s family reached an agreement with the city to ensure it would invest in safety upgrades so that another child wouldn’t die, said Mark Blake, Logan’s father. “We just wanted them to fix one at that time,” he said. “And they came up with a plan to fix three right away because they had two other ones right next to schools in the same exact situation.”

For guidance on how to evaluate which inlets needed safety grates and which needed less aggressive improvements, Mark Blake and the Cedar Rapids officials turned to MacKenzie, whose Denver district had developed a set of criteria for reviewing the safety of open inlets. They would assess the length of pipe, size of the pipe’s entrances, whether there were bends and turns in the pipe, and its proximity to schools and parks.

Cedar Rapids also used the Mile High Flood District’s latest design for grates that are installed at an angle, which are meant to prevent people from being pinned against them during a flood. “And the idea is that the bars would be spaced tightly enough that somebody couldn’t get in there, but they could also act as a ladder or a walkway for someone to get out,” said David Wallace, Cedar Rapids’ utilities engineering manager. For larger culverts, ones that Wallace said were simply impractical to grate, the city put up fencing and signage warning people of the danger during floods.

Cedar Rapids has put grates on 11 drains, with four more expected to be completed by the end of 2022. The city expects to spend a total of about $700,000 on the 15 locations. Flooding caused by debris clogs is a risk, Wallace said, but it can be remedied with a consistent maintenance plan. The city’s teams go out after every rain to pull debris from the grates. It takes one workday for two crews of three people with a backhoe to clear the debris after big storms. They have to do that several times a year, Wallace said. With the diligent maintenance schedule, the grates have not added any additional flooding.

“The idea is to prevent the tragedy that we had here,” Wallace said. “So sure, it adds to the maintenance activities and adds some costs that we otherwise wouldn’t have had to do, but the idea is to prevent what happened. … It’s just a safety, prevention measure that we think is necessary.”

The Mile High Flood District, Colorado’s Larimer County Dive Rescue Team, Colorado State University’s Hydraulics Lab and the engineering company AECOM have been researching how people are injured or killed in drainpipes and have been working on grate designs for different pipe and culvert configurations. The group created a physical model at the university to test its research in simulated flood waters. Part of the team’s work looks into pitch angles, bar spacing and how far away from the pipe entrance a grate should be placed — all aimed at making grates safer and less expensive. The group plans to release detailed data from its work at the World Environmental and Water Resources Congress conference in June. “What we found is really going to allow us to make the grates smaller, which will really bring down the cost,” said Holly Piza, an engineer for the Mile High Flood District. “Which is great because then local governments and municipalities will be more likely to put in safety grates where they’re appropriate.”

The bipartisan Infrastructure Investments and Jobs Act includes funding that could help communities upgrade their drainage systems’ capacity and safety. More than $50 billion in new spending from the bill will go to drinking water, wastewater and stormwater investments over 10 years. A spokesperson with the Environmental Protection Agency told ProPublica that $1.9 billion of that money was going to the Clean Water program, which allows awarded communities to install grates in addition to making other upgrades.

The storm drain accidents recorded across New Jersey during Ida show just how preventable these deaths can be.

Residents of Maple Terrace in the town of Maplewood had been complaining for years about the dangerous and inadequate drainage structure there, a 48-inch pipe sitting on three properties, one on the north side of the street and on two on the south side. Patrick Jeffrey and his wife, Beth, who lived next to one of those homes, had been among those voicing concerns. The flooding caused by the pipe routinely spilled into their yard, and they worried its large opening could be dangerous to adults walking around it or children playing near it.

Over the years, a group of the neighborhood dads developed a routine before and during rainstorms: They’d work together to remove debris from the two inlets to try to keep the flooding down. On Sept. 1, Patrick Jeffrey was doing what he always did; a neighbor was going to meet him near the inlet and help remove debris. But when the neighbor arrived at the hole, he couldn’t find Jeffrey. Fred Meyer, who lived across the street from Jeffrey, joined the search effort.

“There was like a 360-degree waterfall … charging down this hole. There was water everywhere,” said Meyer. “It was terrifying.”

The next morning, Jeffrey’s body was found along a neighboring roadway. He had been pulled into the drainage system and emerged out of a manhole. The father of two, who worked as a vice president and portfolio manager at U.S. Bank in New York, was 55.

“We were always thinking that a kid might fall into this thing,” said Meyer, Jeffrey’s neighbor. “I never thought something would happen to an adult and I never thought it would be someone dying. I still can’t believe it happened. The absolute worst thing that could possibly happen in this scenario actually has.”

One year earlier, in Pennsylvania’s Sewickley Township, a 38-year-old man died the exact same way, trying to clear debris from a pipe in his backyard.

Transcripts from Maplewood town meetings show residents had been asking since at least 2018 for the area where Jeffrey fell to be replaced by an underground pipe, but town leadership was resistant to the idea at the time. When town officials eventually came around to it, officials with New Jersey’s environmental department were against it because they said the area had a natural waterway designation that prevented such a move, according to emails. Had the problem been dealt with years ago, Meyer said, there would have been no open pipe for Jeffrey to remove debris from. He’d be alive to coach his son’s flag football team and cheer on his daughter’s softball team.

After Jeffrey’s death, state officials gave the town permission to install grates over the pipe and said they would grant an exemption that would allow the town to replace the area with an underground pipe, according to meeting minutes. The state didn’t directly answer ProPublica’s questions about why its officials had changed their minds, but in reference to the grates, a spokesperson told ProPublica the state and the town agreed that Maplewood would ask for permission to install the grates to “address the immediate concern for safety.”

The city of Passaic, too, had discussed a dangerous drain before best friends Nidhi Rana, 18, and Ayush Rana (no relation), 21, abandoned their flooded-out car and died after being sucked into the drain during Ida. In July 2020, DoorDash driver Nathalia Bruno had wound up in the same drain but survived after she fled her car during a flash flood.

Bruno recounted her harrowing story in news accounts, and city officials talked about grates and warning signs. But city engineers said that a grate would become clogged, leading to more flooding, and that people might get pinned to them. Mayor Hector Lora also said property owners voiced concerns about permanent flash flood warning signage because of what it could do to property values. Instead, the city focused on strengthening its barricades and moving them further away from problem areas. It also rolled out temporary LED warning signs with each heavy rain and began pursuing grants to elevate the roadway.

Lora said there wasn’t pressure for more urgent reforms back then because Bruno “miraculously survived.”

When asked if there was anything the city could have done more immediately after Bruno’s accident that could have helped save the two friends who later died, Lora said he believes the city did the best it could with the information it had and that no one could have planned or prepared for the devastation brought by Ida. “I think we did everything that municipalities are supposed to do,” he said. “Sometimes crisis and tragedy become the genesis for good policy and initiatives that come later.”

The city is now moving with more urgency, Lora said. He hadn’t heard of the idea of putting grates at an angle, but after speaking with ProPublica and being shown examples of the Denver design, Lora said he has asked his engineers to review the new model. “The tragedy compels me to explore every option,” he said. Officials with MacKenzie’s team in Denver reviewed an image of the Passaic culvert and said their early assessment is that a safe grate could be designed for the location.

Permanent warning signs have also been put in place near the culvert, and the city is pursuing grants to buy a sign that will monitor water depth and alert police and the fire department when it reaches a certain height. Lora is also looking for funds to surround the culvert with a large fence that curves at the top.

As for the pipes in South Plainfield, where Dhanush Reddy and Kevin Rivera were pulled in, it’s not clear if there are plans to do anything; Middlesex County officials, who are responsible for the maintenance of the pipes, declined to answer ProPublica’s questions.

Kavya Mandli no longer lives in New Jersey. She moved to the Atlanta area after the death of her fiance. “My life just went upside down since then,” she said. “I’m still really figuring out what to do. I had to move away from that place because I really couldn’t be myself there anymore.”

She hasn’t escaped the reminders of her loss. There was the trip they were supposed to take to Puerto Rico, two days after his death. There was what would have been his birthday gift — tickets she’d already bought to his first-ever Formula 1 race in October. Then there is their white labrador, Kush, whose name is a combination of their own first names. They were trying to get home to him quickly on Sept. 1; Reddy knew Kush would be frightened by the weather.

Every day, when Reddy got home from work, Kush would run toward the door and the two would tussle like kids. “Kush is so huge, he’s like 90 pounds, but Dhanush just picks him up like a baby and rocks him,” Mandli said.

“I sometimes think, ‘It’s around 5 o’clock, maybe he’ll come home.’”

Doris Burke contributed research.