One fall evening in 2020, Jarell Jackson and Shahjahan McCaskill were chatting in Jackson’s Hyundai Sonata, still on a post-vacation high, when 24 bullets ripped through the car. The two men, both 26, had been close friends since preschool. They’d just returned to West Philadelphia after a few days hang gliding, zip lining and hiking in Puerto Rico. Jackson was parked outside his mom’s house when a black SUV pulled up and the people inside started shooting. Both he and McCaskill were pronounced dead at the hospital.

In the aftermath, McCaskill’s mother, Najila Zainab Ali McCaskill, couldn’t fathom why anyone would want to kill her son and his friend. Both had beaten the odds for young Black men in their neighborhood and graduated from college. Jackson had been a mental health technician in an adolescent psych ward while her son had run a small cleaning business and tended bar. She wondered if they’d been targeted by a disgruntled former employee of the cleaning business. But then the police explained: Her son and his friend had been killed because of a clash on social media among some teenagers they’d never even met.

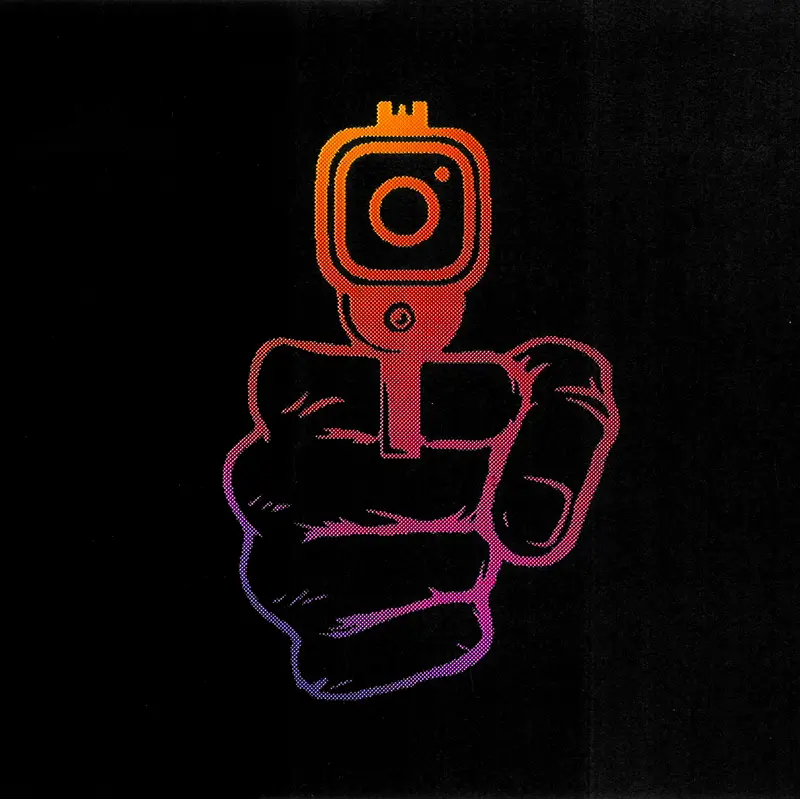

For months, a battle had been raging on Instagram between crews based on either side of Market Street. Theirs was a long-running rivalry, but a barrage of online taunts and threats had raised tensions in the neighborhood. Police had assigned an officer to monitor the social media activity of various crews in the city, and the department suspected that the Northsiders in the SUV had mistaken one of the two friends for a rival Southsider and opened fire. An hour after the shooting, a Northsider posted a photo on Instagram with a caption that appeared to mock the victims and encourage the rival crew to collect their bodies: “AHH HAAAA Pussy Pick Em Up!!”

Jackson and McCaskill died in the first year of a nationwide resurgence in violence that has erased more than two decades of gains in public safety. In 2020, homicides spiked by 30% and fluctuated around that level for the next two years. There are early signs that the 2023 rate could show a decrease of more than 10% from last year, but that would still leave it well above pre-pandemic levels.

Criminologists point to a confluence of factors, including the social disruptions caused by COVID‑19, the rise in gun sales early in the pandemic and the uproar following the murder of George Floyd, which, in many cities, led to diminished police activity and further erosion of trust in the police. But in my reporting on the surge, I kept hearing about another accelerant: social media.

Violence prevention workers described feuds that started on Instagram, Snapchat and other platforms and erupted into real life with terrifying speed. “When I was young and I would get into an argument with somebody at school, the only people who knew about it were me and the people at school,” said James Timpson, a violence prevention worker in Baltimore. “Not right now. Five hundred people know about it before you even leave school. And then you got this big war going on.”

Smartphones and social platforms existed long before the homicide spike; they are obviously not its singular cause. But considering the recent past, it’s not hard to see why social media might be a newly potent driver of violence. When the pandemic led officials to close civic hubs such as schools, libraries and rec centers for more than a year, people — especially young people — were pushed even further into virtual space. Much has been said about the possible links between heavy social media use and mental health problems and suicide among teenagers. Now Timpson and other violence prevention workers are carrying that concern to the logical next step. If social media plays a role in the rising tendency of young people to harm themselves, could it also be playing a role when they harm others?

The current spike in violence isn’t a return to ’90s-era murder rates — it’s something else entirely. In many cities, the violence has been especially concentrated among the young. The nationwide homicide rate for 15- to 19-year-olds increased by an astonishing 91% from 2014 to 2021. Last year in Washington, D.C., 105 people under 18 were shot —nearly twice as many as in the previous year. In Philadelphia in the first nine months of 2022, the tally of youth shooting victims — 181 — equaled the tally for all of 2015 and 2016 combined. And in Baltimore, more than 60 children ages 13 to 18 were shot in the first half of this year. That’s double the totals for the first half of each year from 2015 to 2021 — and it has occurred while overall homicides in the city declined. Nationwide, this trend has been racially disproportionate to an extreme degree: In 2021, Black people ages 10 to 24 were almost 14 times more likely to be the victims of a homicide than young white people.

Those confronting this scourge — police, prosecutors, intervention workers — are adamant that social media instigation helps explain why today’s young people are making up a larger share of the victims. But they’re at a loss as to how to combat this phenomenon. They understand that this new wave of killing demands new solutions — but what are they?

To the extent that online incitement has drawn attention, it’s been focused on rap videos, particularly those featuring drill music, which started in Chicago in the early 2010s and is dominated by explicit baiting of “opps,” or rivals. These videos have been linked to numerous shootings. Often, though, conflict is sparked by more mundane online activity. Teens bait rivals in Instagram posts or are goaded by allies in private chats. On Instagram and Facebook, they livestream incursions into enemy territory and are met by challenges to “drop a pin” — to reveal their location or be deemed a coward. They brandish guns in Snapchat photos or YouTube and TikTok videos, which might provoke an opp to respond — and pressure the person with the gun to actually use it.

In December, I met 21-year-old Brandon Olivieri at the state prison in Houtzdale, Pennsylvania, where he is serving time for murder. In 2017, Olivieri said, he had a run-in with other teens in South Philadelphia after he tried to sell marijuana on their turf. Later, in a private Instagram chat for Olivieri and his friends, someone posted a picture of a silver .45-caliber pistol. Then another member, Nicholas Torelli, posted a picture of cat feces on the sidewalk, with the caption “Brandon took a shit on opp territory.” It was a joke, but the conversation quickly turned aggressive. Later that day, Olivieri asked Torelli to drop an image of their opponents into the chat, so everyone could see what they looked like. Torelli complied, and, according to court records, Olivieri replied that he would “pop all of them.”

When Olivieri, Torelli and two friends encountered four of their opponents later that month, there were heated words, a struggle and three gunshots from the silver pistol. One bullet struck Caleer Miller, a member of Olivieri’s group. Another hit Salvatore DiNubile, in the other crew. Both died; they were 16. Olivieri was convicted of first-degree murder in DiNubile’s death and third-degree murder in Miller’s. (Torelli testified against Olivieri and was not charged.) Olivieri was sentenced to 37 years to life.

DiNubile’s father, also named Salvatore, believes the ability to share threats online encouraged Olivieri and his friends to make them; having made them, they felt compelled to follow through. “You said you were gonna do this guy. Here’s your chance,” he told me. “You try to live up to this gangster mentality that he’s self-created.” Olivieri maintains his innocence and says that he wasn’t the one who fired the fatal shots, but he agreed that he and his friends often hyped one another up by making boasts online. “It’s what we call pump-faking,” he explained.

Last year, as the number of juvenile shooting victims in Washington, D.C., climbed toward triple digits, the city’s Peace Academy, which trains community members in violence prevention, held a Zoom session dedicated to social media. Ameen Beale of the D.C. Attorney General’s Office shared his screen to display a sequence typical of online flare-ups culminating in a fatality.

The presentation started with a photo, posted to Instagram in 2019, showing the local rapper AhkDaClicka on the Metro; the caption mocked him for being caught there, without a gun, by adversaries. Then came a screenshot of private messages between AhkDaClicka and a rival rapper named Walkdown Will that the latter posted derisively on Instagram Live. Next, an Instagram Story from AhkDaClicka insulting another rapper who had allegedly been present at the Metro run-in and a YouTube video of AhkDaClicka rapping about the incident, including the line, “Just give me a Glock and point me to the opps.” Soon afterward, in January 2020, AhkDaClicka was fatally shot. He was 18; his real name was Malick Cisse. That May, police arrested Walkdown Will — William Whitaker, also 18. He pleaded guilty to second-degree murder last October.

Beale’s presentation left some participants dumbfounded. “I cannot believe the level of immaturity and stupidity that’s become the norm,” one wrote in the chat. Another asked the question looming over the session: Had anyone in the city’s violence prevention realm asked the social media companies to limit inflammatory content?

“I don’t think we’ve made much progress,” Beale admitted. When the city had sought to have posts removed, he said, the companies had rebuffed its pleas with vague arguments about free speech. Even if social media platforms did remove a post, 20 people could already have shared it with hundreds or thousands more. And given the pace of online life, you might spend five years trying to block harmful content on one platform, only for all the activity to migrate to another.

I asked a spokesperson for Google, which owns YouTube, about the AhkDaClicka video with the line about the Glock, as well as another video posted last summer, titled “Pull Da Plug.”

It showed a Louisville, Kentucky, rapper and about a dozen other young men apparently celebrating a shooting that had left a man on life support (he later died). The head of the Louisville violence prevention agency had told me that the victim’s family asked Google to remove the video, but it stayed up, collecting more than 15,000 views. The spokesperson, Jack Malon, told me the company generally had a “pretty high threshold” for removing music videos, in part because company policy allows exceptions for artistic content.

My conversations with Malon and his counterparts at Snap and Meta (which owns Facebook and Instagram) left me with the impression that social media platforms have given relatively little thought to their role in fueling routine gun violence, compared with the higher-profile debate over censoring incendiary political speech. Meta pointed me to its “community standards,” which are full of gray-area statements such as “We also try to consider the language and context in order to distinguish casual statements from content that constitutes a credible threat to public or personal safety.” Snap argued that its platform was more benign than others, because posts are designed to disappear and are viewed primarily by one’s friends. I also reached out to TikTok, but the company didn’t respond.

Communities, meanwhile, have been left to fend for themselves. But violence prevention groups are dominated by middle-aged men who grew up in the pre-smartphone era; they’re more comfortable intervening in person than deciphering threats on TikTok. Before the pandemic, an intern at Pittsburgh’s main anti-violence organization scanned social media posts by young people considered at risk of becoming involved in conflicts. The Rev. Cornell Jones, the city government’s liaison to violence prevention groups, told me that the intern had once detected a feud brewing online among teenagers, some of whom had acquired firearms. Jones brought in the participants and their mothers and defused the situation. Then the intern left town for law school and the organization reverted to the ad hoc methods that are more typical for such groups. “If you’re not monitoring social media, you’re wondering why 1,000 people are suddenly downtown fighting,” Jones said ruefully. In early July, a shooting at a block party in Baltimore validated his concern: Though the event had been discussed widely on social media, no police officers were on hand; later, a video circulated of a teenager showing off what appeared to be a gun at the party. The shooting left two dead and 28 others wounded.

A decade ago, Desmond Upton Patton, a professor of social policy, communications and psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, got the first of several grants to study what he called “internet banging.” His research team co-designed algorithms with a team at Columbia University to analyze language, images and even emoji on Twitter and identify users at risk of harming themselves or others. The algorithms showed promise in identifying escalating online disputes. But he never allowed their use, worried about their resemblance to police surveillance efforts that had enabled profiling more than prevention. “Perhaps there is a smarter person who can figure out how to do it ethically,” he said to me.

For now, the system is failing to anticipate violence — and even, quite often, to convict people whose social media feeds incriminate them. In May, three teens were tried for the murders of Jarell Jackson and Shahjahan McCaskill in Philadelphia. At the time of the shooting, two were 17 and the third was 16. Social media activity formed a key part of the prosecutors’ evidence: Instagram posts and video feeds showed the three defendants driving around in a black SUV seemingly identical to the one that had pulled up alongside Jackson’s car. Other posts showed two of them holding a gun that matched the description of one used in the shooting. After a day of deliberations, the jury acquitted them of murder, finding two of the defendants guilty only of weapons charges. The verdict left the victims’ families reeling. “For me and my family, [the trial] was like a seven-day funeral,” Monique Jackson, Jarell’s mother, told me. Afterward, the detective who had investigated the murders speculated to her that jurors on such cases often struggle to grasp the basic mechanics of social media and how essential it is to the interactions of young people. As Patton put it to me: “What we underestimate time and time again is that social media isn’t virtual versus real life. This is life.”

Update, Aug. 9, 2023: This article has been updated to clarify YouTube’s policy for removing music videos.