In 2019, I wrote a story for ProPublica, co-published with The New Yorker, about the dispossession of Black landowners in the South. The story looked at the legal obstacles that families face when they pass their land down without a will, a form of ownership known as heirs’ property. Laws and loopholes allow speculators and developers, among others, to acquire the property out from under families, often at below-market rates. Black Americans lost 90% of their farmland between 1910 and 1997, and the heirs’ property system is one of the primary causes.

I focused on the Reels family of North Carolina, chronicling how they had lost their land to developers but refused to leave it. This land was their home, their freedom, their livelihood, their history and their legacy. They believed so deeply in their moral claim to the land that they would not accept a ruling that it no longer belonged to them. Their story of losing heirs’ property is common in the South, but their determination to protest was unlike anything I had seen. Two of the brothers, Melvin Davis and Licurtis Reels, ended up spending eight years in a county jail for refusing to obey a court order to stay off the land. Their sister, Mamie Reels, and their niece, Kim Duhon, dedicated their lives to protecting the property and freeing Melvin and Licurtis.

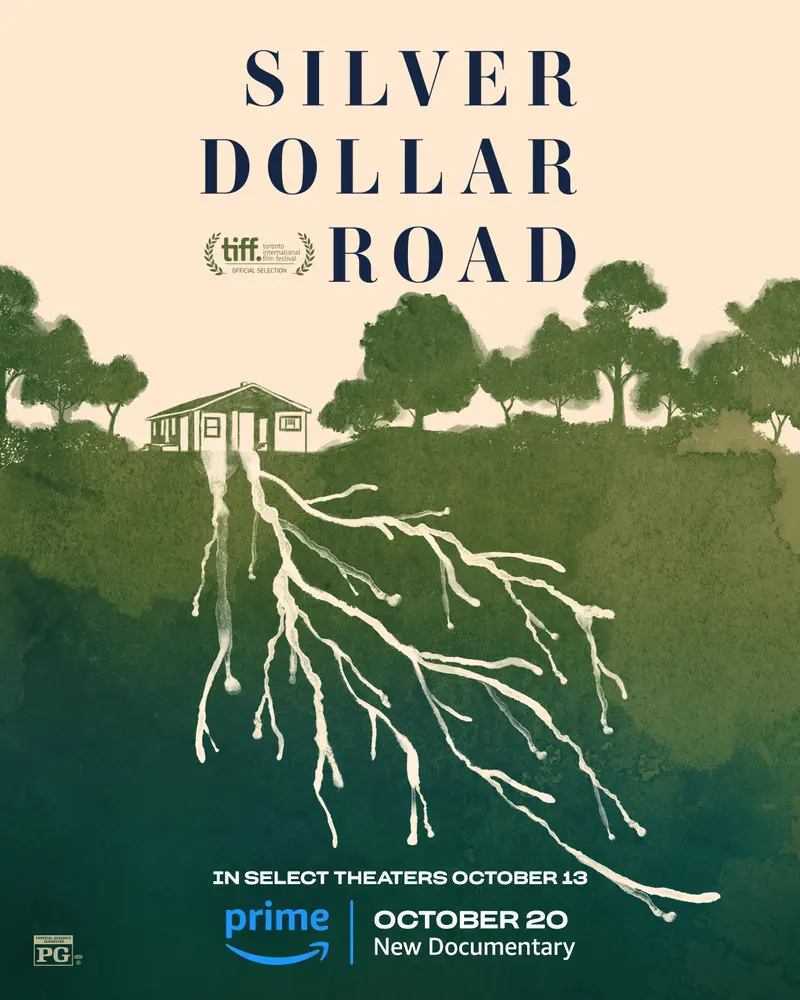

While I was reporting, my editor, Alexandra Zayas, suggested that ProPublica send a videographer to capture the story. For two months, Mayeta Clark filmed while I was investigating. Katie Campbell joined on a few shoots as well. By the time the story was published in July 2019, we had almost 90 hours of footage. We reached out to documentary filmmaker Raoul Peck to see if he might be interested in collaborating on the project. Born in Haiti, Peck has directed documentaries and features about subjects that include Patrice Lumumba, the first prime minister of the Republic of Congo, who was murdered with U.S. and Belgian support (“Lumumba: Death of a Prophet”), the rebuilding efforts in post-earthquake Haiti (“Fatal Assistance”) and James Baldwin’s unfinished manuscript on race in America (Oscar-nominated “I Am Not Your Negro”). I spent several months working with Peck, and then he went off to shoot and write. When he completed a script, ProPublica reviewed it to ensure its accuracy. The resulting film is “Silver Dollar Road,” co-produced by Velvet Film, ProPublica, JuVee Productions and Amazon MGM Studios. It will premiere this evening at the Toronto International Film Festival and will be released on Prime Video on Oct. 20. I spoke with Peck last week about the film and his process. This conversation has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Your most recent films centered around historical figures, like Karl Marx and James Baldwin, and historical forces, like the presumption of white supremacy, and I was curious what it’s like for you to transition to an intimate family story.

The filmmaker I always wanted to be was one who never had a plan. My way of approaching issues or subjects of film is always what, in this moment of my life, seems important, and where can I contribute. I dig into my personal history. Baldwin, Marx, remember, those are stations of my real life. So usually my projects come in a very organic way, and this one did as well.

I was familiar with the topic and, of course, my blood would always boil. But I thought, “OK, there are American filmmakers who are capable of doing this film, I don’t need to immerse myself in it.” Then this came through ProPublica, asking if I would executive produce, and I said, “Of course,” because I thought it was a great story. We had also found a great filmmaker, a young filmmaker, and I thought we could bring him in and allow him to make his second film. Then this filmmaker had to make another project, but by that time, I was deeply involved in it. So I said, “You know what? I need to meet the family.” Once I did, I decided I would direct it. I didn’t look for it, I had many other offers, but I decided to do this one because there was a connection.

When you say there’s a connection, can you talk about that?

Well, some of the cornerstones of what I do are power and abuse of power, history or “denied history,” and injustice. I had this feeling while reading about this family and then seeing the footage that you guys had shot that these were people I knew — that these were situations that I knew, whether through my studies, or in films or history, but also through my own experience in Haiti and Congo.

Initially, you thought you would maybe make a sweeping film about Black land loss and weave the Reels family story in as one element, but then you changed your mind. What drove you to keep this as a family story in the end?

At one point, we had conversations about whether I should bring you into the film. I watched you talking to the family and I felt you were like the daughter of the house, and I didn’t want to lose that — until, you know, I got to a point where I did. There was also your resistance. As a journalist, you wanted to stay a journalist, which I totally respect. You didn’t want to become the subject of your own work. But I’m a filmmaker. My process is to observe, and I try to tell the narrative of my observation.

But then, when I was with the family, the effect of Mamie and Kim, these two women, was clear to me. They were the ones running the show. They were the pivotal people. They were the most courageous. They were the most clear-eyed. They were the most philosophical. Not only is Mamie all those things, but she’s also funny. You could see how much she took on to be the leader. She knew she had to be the joker because she had to take everybody with her. The main characters would be Mamie and Kim, and it was great to have two different generations, two women with different educations and different ways of seeing life. They had to tell the story themselves.

Very often, the studios or networks want a nice, closed-off story, where you tell the story but the subjects still stay on the other side of the fence. Where we are voyeurs, looking at the misery or the happiness or whatever it is of other people, but we don’t feel that they are like us or we are like them. There was no way I was going to go there — take all these moments from this family and sell them. No. My duty as an engaged filmmaker is to make sure that I’m a vehicle bringing these voices to a loudspeaker.

I was thinking back on the first time you and I met — it was before you had met the family — and we talked a lot about private land ownership and the accumulation of wealth and the roots of capitalism. How did those intellectual interests of yours layer into this film, and did they evolve while you were making the film?

In terms of my personal journey, the only one that counts is my journey of making new friends. Kim, Mamie, everybody — I feel they are my family, I feel they are friends. So I would answer your question by saying, the film I try to make is the film that uses my experience and knowledge the way I understand society today, mostly a capitalistic society, and how that society expresses itself in multiple stories. By the way, the story is the same as the one from “I Am Not Your Negro.” It’s the same story about capitalism, racism, colonialism, exploitation, injustice. It’s the same themes again and again. So I felt at home in the sense that this is a continuation of what I’ve been doing.

You say the Reels are your friends. I get asked this question all the time as a journalist when other people see how close I get to subjects. They say, “Well, how do you draw that line between being a journalist and being a friend? Does intimacy ever get in the way of objectivity?” I wonder how you think about those questions.

I’m going to be blunt about this. I grew up with journalists. My first job when I was in university in Berlin was to take photos and do interviews and sell them to newspapers. I’ve seen how the profession has evolved. This desire to be “objective” is a trap. I claim my subjectivity in the sense that I base my films on objective matter, on solid research, empirical material, theory, etc. But then as an artist, I use my subjectivity, and I say what I have to say. That’s the only way to evade the trap. At this point in the debate over truth, I must talk about what I feel and think and be transparent about it.

I wanted to talk a little bit about the style of the film. The film starts quietly. We’re on the land, we’re with the Reels, we’re living in their memories and then the pressure and the drama in their story build gradually. Could you talk me through why you made that choice?

One of my main concerns with this film was how do I avoid the cliches — the cliches of the job as a filmmaker but also the cliches about Black people in the South. How do I give these people power? Because of the algorithms now, the streaming platforms want documentary filmmakers to tell the whole story in the first one to three minutes. But once you do that, you’re basically making a product — you’re not telling a very specific story that can change your mind about even the way you watch films. So if I had gone that way for an opening, it would have been just another terrible story about a Black family in the South. You would maybe see it once and then forget about it.

But I wanted to make a film where you first establish real people, people you want to watch and listen to, people you will remember. So it’s a different type of construction, and I knew that it was the only way to tell the story instead of saying up front that two brothers were in jail for eight years for nothing. If you don’t understand the price, the real toll on the whole family — if you can’t identify with the people — you will just have pity. But I want you to have a connection, and I want the anger to be your anger about the injustice, so it’s felt as an injustice to you too.

I’m curious about your writing process. You went through all our footage, and then you went on shoots of your own. Were you using our footage almost as archival and then building around it?

Exactly that. I think we made the best use of your work, Mayeta’s work and my work. In this case, it was a collective. It’s different, but it’s still my signature.

What makes it your signature?

It’s the themes, but another part of it is the subjectivity. You know, there are things that Mamie says that I would probably analyze differently, because I researched “the other side,” but this is what she thinks and she has the right to say it, because that’s her life, that’s what her experience tells her. So, somehow, I gave her my own personal subjectivity. She is the one taking my place. Usually, my films are more conceptual, and there is a voice-over that I write. But here, it was mostly their interviews that I used as the material of the dramatic narration. It’s not unlike what I did in “I Am Not Your Negro.” I had to come to the same humbled attitude — to say, “No, it’s Baldwin’s film. He is the one talking and I’m just helping.” I’m a maker-translator, but I have to be in the background.

I once heard you say that you’re not an optimist and you’re not a pessimist —

I said I’m a realist.

I wonder how this film fits into that framework for you?

In the film, Mamie says, “What are you going to do with us, poor people?” I can use that phrase in France, in Germany, in the United States, in Congo. That’s a central question. I don’t feel like the film is about the past or what happened over the past eight years. It’s really a confrontation with today.

Actually, Mamie first says, “What are you going to do with Black people?” Then she corrects herself and says, “What are you going to do with us, poor people?” And that’s a class analysis. Those, for me, are great moments, where Mamie is more than Mamie. Those are the moments that will stick. The moments that are provocative. Mamie isn’t reciting. She’s in it. It comes from her.