This story was produced in partnership with WBUR. WBUR’s investigations team is uncovering stories of abuse, fraud and wrongdoing across Boston, Massachusetts and New England. Get their latest reports in your inbox.

When the mayor of Revere, a working-class city north of Boston, began looking for a new police chief in 2017, he wanted a leader to clean up what he described as the “toxic culture” within the department.

Mayor Brian Arrigo brought in a consultant to help pick the city’s top cop, who oversees more than 100 officers and civilian employees. The consultant, a former police chief in another Boston suburb, tested four candidates — all internal — for attributes such as decisiveness, initiative, leadership and communication skills. None of the candidates scored high enough to persuade the consultant that they would do the job well.

“No city should settle for a Police Chief who cannot deliver an ‘Excellent’ performance when competing for the Police Chief’s position,” he reported to the mayor.

Nevertheless, Arrigo chose one of those four candidates for a three-year interim chief role and appointed another, then-Lt. David Callahan, as chief in 2020. An investigation by WBUR and ProPublica found Callahan not only fell short on the assessment but was also steeped in the toxic culture the mayor deplored.

In 2017, the same year that Arrigo started searching for a chief, Callahan was accused of bullying and sexually harassing a patrolman and “creating an atmosphere of fear.” In the fallout, the 40-year-old patrolman has been on paid leave for more than a year and is seeking an “injured on duty” retirement status, which would cost the city at least $750,000 before the typical retirement age of 55. Callahan disputes those allegations. He did acknowledge in an interview with WBUR and ProPublica that, before becoming chief, he sent a sexually explicit image to another officer.

“It was a mistake,” he said. “It shouldn’t have happened. And I owned up to it and it’ll never happen again.”

Callahan’s selection from an underwhelming pool of candidates illustrates the predicament of Revere and other municipalities that are constrained by regulations from hiring outsiders for the key position of police chief.

“If you restrict the search process to somebody who is already inside the department, you’re making it a lot more difficult for any sort of substantive change to take place,” said Carl Takei, a senior staff attorney at the ACLU focused on police practices.

In a wide-ranging 90-minute conversation in a conference room at Revere police headquarters, Callahan defended his record. He said that he is revising the department’s policies so it can obtain state accreditation, and that he is trying to make it more diverse and welcoming. “It’s not like the kind of good old boys’ network anymore,” he said.

He added that he’s willing to take unpopular steps when necessary, citing an investigation a decade ago of a Revere colleague in a public corruption case, for which he received a commendation from the FBI. “I’ve gone against the grain, and I’ve taken a lot of heat for it,” he said.

In a separate interview with WBUR, Arrigo said he would give Callahan an “A” for his performance as chief. While some critics say Callahan has applied discipline unevenly, Arrigo said the chief has stood up to the department’s culture as if he were an outsider rather than a veteran of three decades on Revere’s force. Still, the mayor emphasized that his options were limited by a decades-old requirement that the chief of police in Revere be chosen from within the department.

In fact, after Arrigo received the candidates’ assessment scores in 2017, the mayor urged the City Council to amend the hiring rule so he could look outside the Police Department. “The fact of the matter is we are currently constraining ourselves to a limited pool of candidates when selecting someone for one of the most important jobs in the city of Revere,” he told the council. His goal, he said, was to choose from the best candidates anywhere “in the name of public safety.” The council didn’t budge.

Restrictions on hiring police chiefs from outside department ranks are common in Massachusetts. In Waltham, which has an ordinance similar to Revere’s, two chiefs who were promoted internally became embroiled in scandal. More than 60 other Massachusetts municipalities abide by state Civil Service Commission rules for how to appoint a chief. This means that the chief is selected from within the department, based on the highest scores on the civil service exam, unless the city specifically requests a statewide search, which hardly ever happens. According to Massachusetts officials, there have been 32 civil service appointments for police chiefs within the last five years. All have been internal promotions, and none of the municipalities considered outside candidates.

The colonel who heads the Massachusetts State Police also had to be hired from within its ranks until 2020. The legislature dropped the requirement in the wake of a sweeping overtime pay scam in which more than 45 troopers were implicated and at least eight pleaded guilty.

Police departments in at least two other states face similar constraints. New Jersey law prevents most municipalities from looking outside their departments for chiefs, and California authorities linked internal hiring mandates in one city to alleged civil rights abuses by police.

Police unions and local elected officials often support hiring from within. It’s seen as a way to reward veterans of the force for their service and to keep political allies close. Having a chief who grew up in the area and knows the community may also be an advantage.

Callahan pointed to these homegrown benefits when asked about internal hiring mandates for police chiefs. He said while it depends on what an individual department needs, it can be difficult to bring in someone from the outside.

“There’s a lot of animosity because you’re going to have people in the department that are upset that they weren’t chosen for the position,” he said. “They’re not necessarily going to cooperate with the new person who’s hired, and there’s going to be some friction.”

But with police departments facing demands for reform nationwide, some experts say one way to address problems such as toxic cultures, racial discrimination, poor training or use of excessive force is to bring in an outsider.

Chuck Wexler, executive director of the Police Executive Research Forum, a Washington, D.C.-based think tank, said internal hiring mandates are outdated and can be counterproductive for troubled departments.

“To simply limit your department and say, ‘We’re not going to look at anyone outside,’ I don’t think that’s good management, period,” Wexler said.

For more than four decades, the Revere Police Department has struggled with corruption and ineffective leadership by chiefs hired from within. A Revere lieutenant was promoted to chief in 1980 after attaining the highest score on the civil service exam. He had purchased a stolen copy of the test from an exam theft ring and was sentenced to four years in prison in 1987.

In that era, Revere typically chose the internal candidate for chief of police who scored highest on the state civil service exam. That changed in 2001, when then-Mayor Thomas Ambrosino wanted the freedom to hire someone regardless of exam results and to have more control over the terms and length of the appointment.

“My recollection is that I was anxious to remove the police chief position in Revere from civil service because I didn’t think that was the most effective way of choosing a police chief,” Ambrosino, who is now city manager in Chelsea, said in an interview.

First, he needed the support of the City Council. They reached a compromise. The council agreed to take the chief’s position out of civil service, and the state approved the move. From now on, the chief would be chosen from within the ranks of the Police Department and no civil service exam was required.

Ambrosino recalled that the council wanted to please the police unions by making sure that the chief continued to be hired from inside. Ambrosino said he considered it the cost of getting the deal done. But he now says the ordinance hamstrings the mayor’s ability to choose the best candidate for the job.

“As a chief executive, you want to have maximum flexibility. You would want to have the ability to go outside the department if you felt you didn’t have a really strong qualified candidate within the department,” he said. “So for that reason, it’s, in my opinion, not a great policy.”

More recent mayors have sought the power to choose someone from outside the department, but they couldn’t persuade the City Council. In 2012, under pressure from then-Mayor Dan Rizzo, the chief resigned and stayed on as a captain, according to the Revere Journal. Rizzo said the Police Department lacked leadership and clear direction, and he wanted the option to pick an outside candidate.

Two consultants to the city would later express similar concerns. In 2015, the year that Arrigo was elected mayor, the Collins Center consulting group said in a draft report that the department’s culture was “very militaristic” and the “lack of unity between the command staff members is most alarming.” Deploring the “fair amount of distrust” among Revere police at all levels, the consultant concluded the city’s internal hiring requirement for its police chief “limits the ability of the department to get the best candidate for the job.”

The other consultant, Ryan Strategies Group, evaluated Callahan and the other three internal candidates in 2017 for police chief. Headed by a former Arlington, Massachusetts, police chief, it administered a series of exercises and tests over multiple days. Each candidate role-played a counseling session with a disgruntled subordinate, led a mock community meeting and completed a written take-home essay.

No candidate scored in either of the two highest ranges, “excellent” and “very good.” The highest of the four scored a low “good,” and the others were “satisfactory,” according to Ryan group’s report. Callahan was one of the top two scorers, according to a person who requested anonymity to discuss individual results. Callahan said that he didn’t know his score or receive any feedback on his performance. He, like the other three candidates, said that the testing was fair and thorough.

The Ryan group did not review personnel records. Besides Callahan’s issues, the city had settled a sexual harassment complaint in 2008 against 13 defendants, including one of the other candidates, Steven Ford. He did not admit any wrongdoing. Another candidate, James Guido, whom Arrigo named as interim chief in 2017, would be sued in 2019, along with the Revere police department, by a female officer who accused him of unfair discipline and retaliation because of her gender. In a deposition, Guido disputed the allegations. The case is pending.

During a heated 2017 meeting with the council, Arrigo said that both the Collins report and the candidates’ scores on the Ryan group’s assessment showed why the city needed to look outside the department for the next police chief. “We owe it to ourselves, we owe it to our city, to have an expanded pool of candidates,” he said.

Ryan Strategies Group also performed an organizational review of the department at Arrigo’s request. It revealed concerns about morale. It also found the department was shirking best practices by not conducting regular audits of property and evidence, and had failed to report to the Suffolk County District Attorney’s Office that an audit found discrepancies in drugs and guns.

The Ryan group’s report strongly opposed a requirement to hire an internal candidate as chief. “There are times when the culture of a community and/or Department become so politicized or polarized that it is necessary to be able to consider a candidate who is not overly involved with local politics or enmeshed in long standing conflicts,” it said.

The council sent Arrigo’s request to change the ordinance to its public safety committee, where it was never brought to a vote. Revere City Councilor Patrick Keefe, who opposed the mayor’s proposal at the time, said that he’s confident in Callahan’s leadership, but he would be open to expanding the pool of candidates for chief in the future.

“I would probably prefer to have the chief of police be an internal candidate, but if you don’t have the best candidate, sometimes you have to think of other options,” he said.

WBUR reached out to multiple city councilors to ask their opinion on the ordinance. Only Keefe responded.

At Callahan’s swearing-in ceremony in July 2020 on the steps of City Hall, the new chief told a crowd thinned by the pandemic that he would honor the same values he’d practiced for almost 30 years at the department. “Since my first day, I have always treated everyone fairly and with the respect they were due,” he said. “I’m committed to serving the community this way, and I will instill these values in the men and women that will be following my lead in the Revere Police Department in the future.”

His appointment capped a steady rise through the ranks. After joining the department in 1991, the Revere native became a lieutenant in 2003. He served as the commander of the Drug Control Unit and was assigned to the Criminal Investigation Unit. In 2012, the FBI recognized Callahan for his “exceptional assistance” in the bureau’s investigation into a public corruption case involving a Revere police officer. As a lieutenant, he was among the highest paid Revere employees. In 2019, he made $213,500, including $72,700 for working details or overtime. Callahan has a five-year contract as chief, and his current salary is $192,000.

But Callahan’s behavior hasn’t always been exemplary. This past May, Callahan testified at an arbitration hearing in City Hall over his role in the firing of an officer. Under cross-examination by union attorney Patrick Bryant, and again in an interview with WBUR and ProPublica, Callahan admitted that, while he was a lieutenant, he texted a sexually explicit image to a patrolman. The patrolman passed the image, which depicted the Virgin Mary superimposed on a vagina, to others in the department, according to screenshots seen by WBUR and ProPublica. According to notes of the testimony taken by Bryant’s law clerk, Callahan said he was never disciplined for his actions.

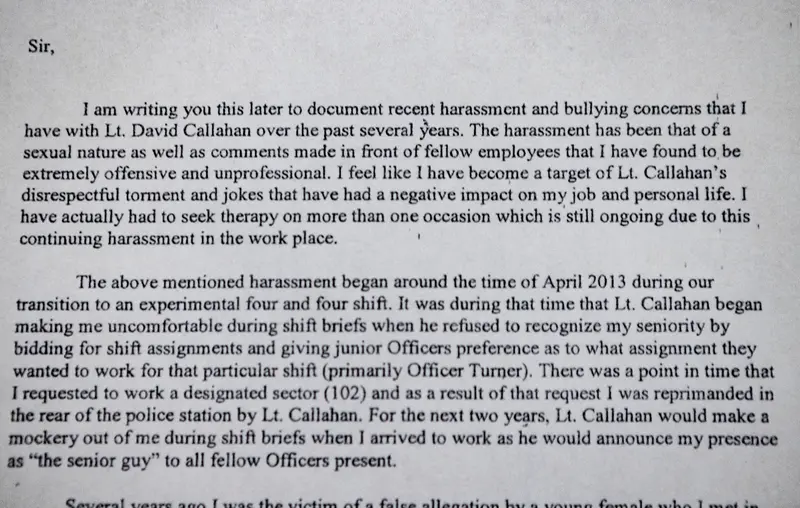

The most serious allegation against Callahan emerged in March 2017, when Revere police officer Marc Birritteri filed a formal complaint to then-police Chief Joseph Cafarelli. It outlined “harassment and bullying concerns that I have had with Lt. David Callahan over the past several years,” according to documents obtained by WBUR and ProPublica.

“I feel like I have become a target of Lt. Callahan’s disrespectful torment and jokes that have had a negative impact on my job and personal life,” Birritteri wrote. “I have actually had to seek therapy on more than one occasion which is still ongoing due to this continuing harassment in the work place.”

In his complaint, Birritteri alleged that Callahan repeatedly called him a “rapist” in front of fellow employees, apparently alluding to a sexual assault allegation against him. Birritteri wrote that a three-month investigation determined that he had not committed any wrongdoing, and he was never disciplined.

Callahan also told Birritteri that he needed “to drop a load in another whore so she can take the rest of your paycheck,” according to Birritteri’s complaint. The comment referred to a child custody dispute that Birritteri was going through at the time, the complaint stated.

At least three officers told WBUR they witnessed Callahan’s taunting of Birritteri and described it as relentless, including Revere Police Patrol Officers Association President Joseph Duca and two others who declined to be named for fear of retaliation.

Callahan disputed these allegations. He said no one told him about the complaint for 11 months after it was filed. “I never knew there was a problem,” he said.

A review of Revere police records shows that Birritteri’s complaints were never investigated by internal affairs, and Callahan was not disciplined. Department policy prohibits “harassing conduct” that “creates an intimidating, hostile, or offensive work environment.”

In a letter sent to Arrigo on April 12, 2017, then-chief Cafarelli informed the mayor that he had been made aware of an “ongoing pattern of psychological abuse directed at Officer Birritteri at the hand of Lieutenant Callahan.” The verbal abuse, Cafarelli wrote, was “occasionally sexual in nature in the presence of other officers.” Describing Callahan as a “domineering supervisor who leads by creating an atmosphere of fear,” Cafarelli recommended that the mayor place Callahan on administrative leave pending a full investigation by an outside body. The recommendation wasn’t followed.

Two months later, Birritteri reported to the department that the bullying was continuing. “I am being further harassed and intimidated by employees and supervisors,” he stated. He was referring to friends of Callahan’s in the department, according to two officers, who declined to be identified for fear of retribution.

That October, the city reached a settlement with Birritteri, acknowledging that he presented “credible complaints of harassment” while on duty. The city paid for his legal fees and insurance co-pays for mental health therapy, and it reinstated 38 sick days.

In 2018, when he was no longer chief, Cafarelli sued the city and the mayor. He alleged that Arrigo failed to restore him to his former position as lieutenant because Cafarelli had advocated for Birritteri and had recommended putting Callahan on leave, according to court documents. Cafarelli said in the lawsuit that Arrigo and Callahan were “very good friends” and that the mayor had already decided to name Callahan as police chief. The city and the mayor responded in court documents that Cafarelli had not given timely notice of his intent to return to his old rank. This past April, a superior court judge dismissed the retaliation claim but allowed a breach of contract claim to go forward. Cafarelli said he now works as a private contractor for the U.S. government.

Arrigo acknowledged that the city substantiated Birritteri’s complaints and said that he had spoken with Callahan about the allegations. Still, the mayor said the harassment did not give him pause when he appointed Callahan as chief.

Birritteri continued to receive counseling, according to his correspondence with the city. In 2021, he and the mayor reached another agreement that would pay him $65,000. The patrolman promised not to disparage the city, the mayor or Police Department. The mayor also agreed to not fight Birritteri’s request with the city Retirement Board for a special type of retirement for officers injured on duty. That claim is pending. If granted, he would likely collect pay of more than $50,000 a year, or almost three-fourths of his highest salary.

Allegations about Birritteri’s own conduct as a police officer have also cost the city. In 2012, he was sued by a man who said he was assaulted at a parade and alleged that Birritteri failed to intervene. The city settled the case for $15,000, according to the city solicitor, and all claims were dismissed. And in a September 2021 lawsuit, a woman alleged that Birritteri violated her civil rights by wrongfully arresting her and unlawfully searching her car. A $36,000 settlement was reached in April, according to the solicitor. Duca, in his capacity as union president, said that Birritteri denies wrongdoing.

Like many internally hired police chiefs, Callahan is a political ally of the mayor’s. Callahan has donated close to $5,000 to Arrigo’s campaigns over the last six years and has knocked on doors on Arrigo’s behalf. He said he was “very active” in supporting Arrigo’s election because he agreed with the mayor’s vision for the city. Both Callahan and Arrigo said that his political support for the mayor had nothing to do with his hiring as chief. Arrigo interviewed the top two candidates, according to people familiar with the process. The mayor said he also sought feedback from other police officers and community members.

As chief, Callahan has feuded vehemently with the patrolman’s union — for example, over his decision to restore a shift schedule that the union criticized for contributing to burnout. Callahan, who has the shift rotations posted on the wall of his spacious office, said the schedule he has implemented is better for public safety. Duca is so dismayed with Callahan that he’s now open to hiring an outsider as chief. Duca said the police force would benefit from looking elsewhere for future chiefs instead of having to “choose from the best of the worst” candidates.

Arrigo said he has seen Callahan “hold the department to a higher standard than prior chiefs.” The mayor cited the firing of a patrolman, Rick Griffin, the son of a retired sergeant. The mayor determined that Griffin, while in his probationary period, was allegedly untruthful when questioned by the police’s internal affairs department, according to court documents. Griffin was asked about an evening in which he argued with his girlfriend and then was in a car accident, according to Griffin and Duca. Griffin denied the allegations and said he was not formally interviewed before he was let go. He filed a complaint in superior court against the Civil Service Commission, the city and the mayor, alleging that his termination was politically motivated, because his family backed an opponent of Arrigo’s, and that he was denied due process. The case against the city and the mayor is pending, while the complaint against the Civil Service Commission is on appeal.

Also fired was another patrolman, Youness Elalam, who had sexual contact with a custodian in a private room at the police station while off duty, according to a state police investigation. Elalam and the custodian told investigators that, while she was uncomfortable with having sex at work, they were in a consensual relationship, documents show. Elalam told WBUR that he was treated harsher than other officers facing discipline because he is Muslim and Moroccan. Elalam’s firing was the subject of the arbitration hearing that Callahan testified at in May.

During that hearing, Callahan said that, as a lieutenant, he had become aware of allegations that another senior officer had sex with a 911 dispatcher throughout the police station and in department vehicles while on duty. Callahan acknowledged at the hearing that he had an obligation to investigate the information he received but didn’t do it thoroughly, according to notes of the testimony. The senior officer, who denied the allegations, wasn’t reprimanded.

“If you’re friendly with the chief and supportive of his interests, you again have your own kind of private internal affairs process,” said Bryant, the union attorney representing Elalam.

Callahan declined to comment on the case, saying it’s still pending. According to Elalam, a tentative settlement was reached last month, in which the city will pay him $25,000 and reinstate him on the force. He will be placed on unpaid administrative leave and will be allowed to resign in good standing, with favorable letters of recommendation from the chief and the mayor.

“It’s a huge win and relief. I fought so hard so I could continue to be a police officer,” he said. “I don’t have to deal with Revere anymore, and I can move on to another chapter of my life doing the job I love.”

In 1999, two years before Revere adopted its ordinance requiring police chiefs be hired from within, Waltham instituted a similar policy. Promoted under the new rule, Edward Drew became chief in 2000 after 26 years in the Waltham department. In 2008, Drew paid a $1,000 fine to the State Ethics Commission for interfering with the hiring process to help his daughter gain a position on the force. Drew, who waived his right to contest the commission’s findings, did not respond to emails or phone messages.

While Drew was being criticized for favoritism, Waltham Mayor Jeannette McCarthy tried to broaden the selection process to external candidates. The measure was tabled by the City Council and hasn’t been brought up again. McCarthy, who has been mayor since 2004, did not respond to requests for comment.

After Drew retired from Waltham’s force, he was replaced by Thomas LaCroix, who resigned after being found guilty in 2013 on two counts of assaulting his wife. LaCroix died the following year.

Waltham City Councilor Kathleen McMenimen said she voted in favor of the internal hiring mandate in 1999 after hearing several potential candidates for chief voice their support during a council meeting. McMenimen, still a councilor, said she remains supportive of the ordinance, despite the tarnished chiefs, because she believes internal candidates are the most knowledgeable about the city.

“They understand their rank and file, they understand their superior police officers, they understand the city, its neighborhoods and its population, and its demographics,” she said. “And they understand the laws that they are required to adhere to.”

Scandals involving chiefs hired from within have also cropped up in New Jersey. As a result of a century-old state law and Civil Service Commission rules, most smaller New Jersey municipalities must hire chiefs internally.

In Caldwell, a few miles northwest of Newark, Chief James Bongiorno, who joined the force in 1996, was accused of creating a hostile work environment and violating the civil rights of two female officers.The town settled the cases in 2019 for a total of $240,000. Two years later, the town reached a $375,000 settlement with a former lieutenant who alleged Bongiorno created a hostile work environment. Bongiorno did not acknowledge wrongdoing either time. He remains at the helm of the department.

South of Trenton, in Bordentown, then-police Chief Frank Nucera allegedly assaulted a Black teenager while the young man was handcuffed. Nucera, who then retired after 34 years on the force, was convicted in 2019 of lying to the FBI in connection with the investigation. Federal hate crime charges were dropped after two juries failed to reach a verdict.

Police unions in New Jersey have pushed to keep the internal hiring requirements.

“Many times police unions are in support of not bringing an outsider because even though they’re not the chief, everybody below has this hope that they might be chief,” said Brian Higgins, retired chief of the Bergen County police and a lecturer at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice.

In 2021, the Atlantic City Police Department’s largest union sued the state, which is in charge of staffing decisions for the department, when officials signaled a move to expand the search for chief to external candidates. Union President Jules Schwenger said that a new chief will soon be named. “He is from our department and very qualified for the position,” Schwenger said, adding the lawsuit is “on standby.”

Bakersfield, California, reached a settlement in 2021 with the state’s Department of Justice, which had been investigating alleged civil rights abuses by city police officers. As part of that settlement, and to avoid further litigation with the state DOJ, the city will have a ballot referendum on whether to remove a requirement to select the police chief from within the department. This November, voters will have the final say on how the chief is hired.

Arrigo, Revere’s mayor, is up for reelection next year. He said that he would still like to see the ordinance amended to allow the hiring of an outsider as chief, but he doesn’t expect it to happen soon. “That may be for the next mayor,” he said.

Alex Mierjeski of ProPublica contributed research. Yasmin Amer of WBUR contributed reporting.