Twelve years ago, ProPublica set out to build a first-of-its-kind tool that would allow users, with a single search, to see whether their doctors were receiving money from an array of pharmaceutical companies.

Dollars for Docs generated a huge rush of interest. Readers searched the database tens of millions of times to see if their doctors had financial ties to the companies that made the drugs they prescribed. Law enforcement officials used it to investigate drug company marketing, drug companies looked up their competitors and doctors searched for themselves.

A trove of recently released documents offers the public an unvarnished look inside those relationships from the perspective of drug companies themselves. The material shows company officials worked to deflect the media scrutiny even as they sought to take advantage of relationships that they had built with doctors they were paying significant sums of money.

The documents were published online by the University of California San Francisco and Johns Hopkins University and became available as a result of drugmakers settling lawsuits against them for their role in the opioid crisis. These are exactly the kinds of documents we wanted to see when we started working on the Dollars for Docs series in 2010, but of course, no one was willing to show them to us.

Reading them should give patients even more pause about the financial entanglements their doctors have with the drug industry and spur them to ask questions (we have some ideas about specifics below).

The Washington Post mined the records and found that more than a quarter of the 239 medical professionals ranked as top prescribers by opioid maker Mallinckrodt Pharmaceuticals in 2013 “were later convicted of crimes related to their medical practices, had their medical licenses suspended or revoked, or paid state or federal fines after being accused of wrongdoing.” The article was replete with examples of doctors whose problems were well known but who were targeted anyway by sales representatives.

This was a familiar finding. Back in 2010, we found that hundreds of doctors paid by drug companies to promote their drugs had been accused of professional misconduct, were disciplined by state boards or lacked credentials as researchers or specialists.

The document trove included some mentions of our earlier work.

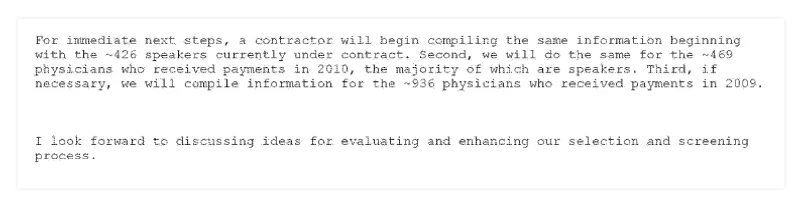

Among them: a 2010 email from a senior director of global compliance at Cephalon Inc., a small drug company that was subsequently acquired by Teva Pharmaceuticals.

In the message, the director notes that what ProPublica found — Cephalon had paid doctors who had been sanctioned by their states to deliver promotional talks on its behalf — was, indeed, true, and that the company was undertaking a review of all of its doctors in light of our findings.

Another document included a list of those doctors.

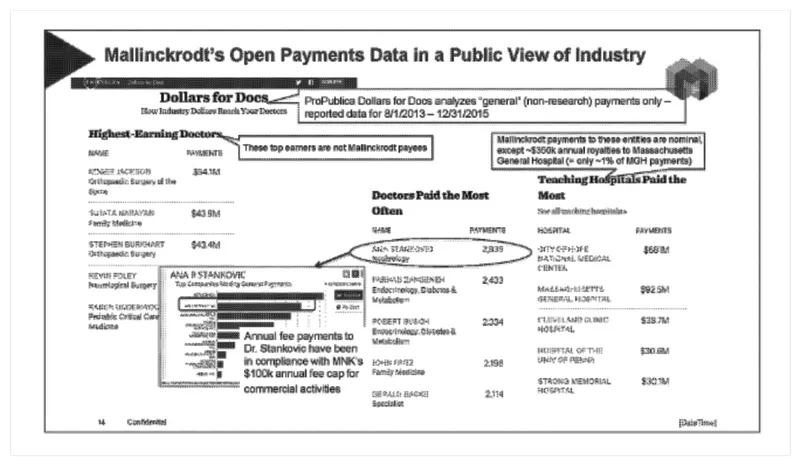

And there’s a 2017 presentation from an official at Mallinckrodt about the state of transparency around payments to doctors. It called ProPublica the “most thorough and vocal media source re: Open Payments data. Their analyses and searchable database are likely the go-to place for anyone wanting to do a comparison of companies and physicians.”

Our Dollars for Docs data often was picked up by news outlets across the country, including WNBC-TV in New York City. In one document, a spokesperson for the company Covidien was happy that the reporter had not asked about Exalgo, a new opioid made by the company. “Based on our conversation, I do not believe that the reporter is aware of Exalgo — and I am certainly not planning to make him aware,” she wrote in 2013.

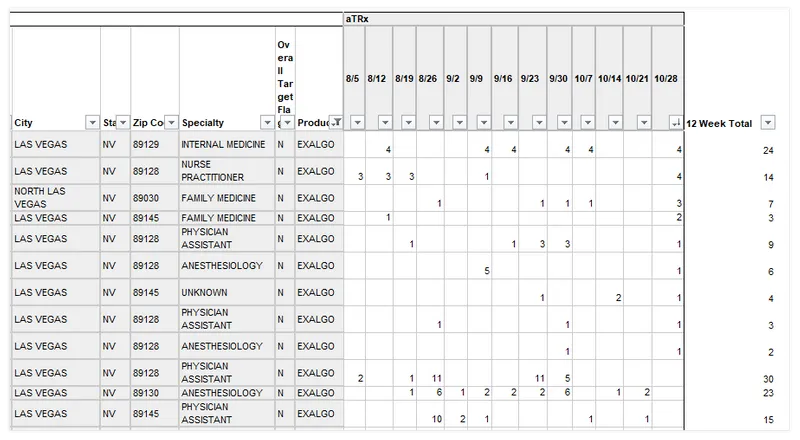

The document trove also shows firsthand how drug companies targeted doctors and used information purchased from data brokers to rank them and gain insight on how many of their drugs each doctor prescribed each week.

When we first started working on our stories, we were very eager to see what pharma drug reps knew about the prescribing practices of doctors. So we asked a company then called IMS Health, which purchased data from pharmacies on which drugs each doctor prescribed and then sold it to the drug companies, if it would sell that data to us. IMS, now known as IQVIA, told us we could not buy the data at any cost.

The document trove includes a number of samples of what that data looks like and makes clear why the industry was so reluctant to have it come into public view.

The following chart was put together for Covidien about Exalgo. For every doctor in the Las Vegas region, it shows their prescribing, by week, of the drug and notes whether they are a “target.”

Documents then show how such information was used when meeting with doctors. In this email, a Covidien drug rep brags about how she was able to turn a doctor’s office staff into allies who would feed her information and talk up the company’s drugs to the doctor. “The nurse got very excited ... and wanted to know all about the product, the coverage, how to use it, etc. She even took the liberty of detailing the doctor when he walked into to (sic) lunch as well.”

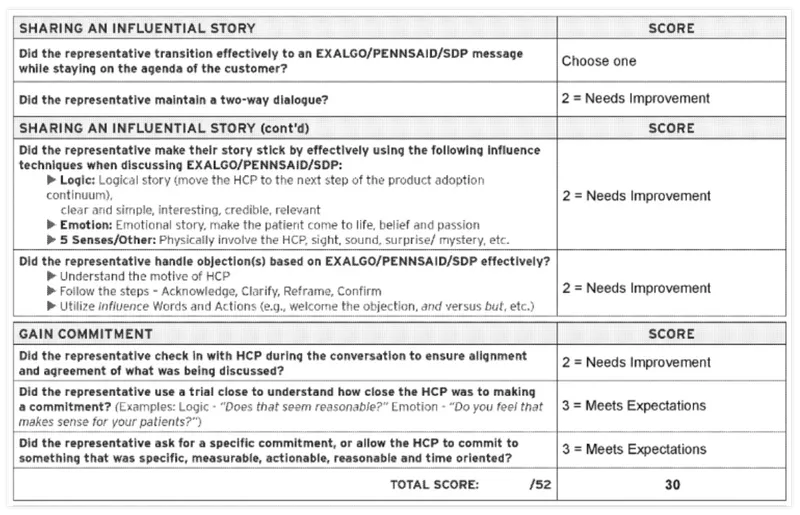

The documents also showed how closely Covidien measured the performance of drug reps in getting doctors to prescribe their drugs.

Covidien spun off Mallinckrodt in 2013 as a specialty pharmaceutical company, managing drugs such as Exalgo. (Mallinckrodt stopped promoting Exalgo in 2015 and no longer sells it.) Covidien focused on medical devices and was acquired by Medtronic.

In 2020, Mallinckrodt agreed to pay $1.6 billion to settle with states and the federal government for its role in the opioid crisis. That figure has since grown to $1.725 billion. In response to a request for comment, a spokesperson for the company sent a statement identical to one it had sent to the Post: “While Mallinckrodt does not agree with the allegations regarding decade-old issues, it has spent the past three years negotiating a comprehensive, complete and final settlement that resolves the opioid litigation against it, provides $1.725 billion to a trust serving affected communities, and allows Mallinckrodt to continue to serve patients with critical health needs under an independently monitored compliance program.”

This year, Mallinckrodt also agreed to pay $260 million to resolve allegations that it underpaid rebates to the Medicaid program and paid illegal kickbacks related to another of its drugs, H.P. Acthar Gel. As it happens, ProPublica has also written about that drug, raising questions about the public spending on it in light of questions about its efficacy.

We stopped updating our Dollars for Docs tool in 2019 because the government’s Open Payments database is robust and refreshed annually and has gotten better with time.

Still, searching through these documents reinforced my view of how important it is for patients to know about their doctors’ relationships with drug companies and talk directly to their doctors about the drugs they are prescribed.

Here are some of the questions you may want to ask:

- What type of work do you do with these companies?

- Have you prescribed me any drugs that are manufactured by companies you’ve taken payments from?

- Are there non-drug alternatives that I may want to consider first?

- Are there less expensive generic alternatives to the drugs you have prescribed?

- What devices have you used in my care that are manufactured by companies you’ve taken payments from?

Have you used Dollars for Docs or Open Payments? What have you found? I’d love to hear your story.