In the years since his byline first appeared in The New Yorker in 2006, Patrick Radden Keefe has become known for his revealing portraits of powerful people who refuse to speak to him. It is a testament to Keefe’s prowess that his subjects end up feeling more lifelike in his stories — more brazen, vulnerable, even sympathetic — than they do in their own memoirs and authorized biographies. This might explain why El Chapo, the Mexican drug lord and the focus of two of Keefe’s articles, wanted him to ghostwrite a book about his life — an assignment that Keefe politely declined.

Keefe’s recent output has cemented his reputation as one of the most popular and thrilling journalists at work today. In 2018, he published “Say Nothing,” a rigorously psychological account of the Troubles in Northern Ireland. A bestseller, it was followed by the hit podcast “Wind of Change,” a picaresque tour of the Cold War’s cultural front, and last year’s “Empire of Pain,” a meticulous investigation of the Sackler family’s role in the opioid crisis.

This summer marks the publication of “Rogues: True Stories of Grifters, Killers, Rebels and Crooks,” which collects a dozen of Keefe’s stories for The New Yorker, including his profiles of the celebrity chef Anthony Bourdain, the Hollywood producer Mark Burnett and the mass shooter Amy Bishop. Keefe has never had a dedicated beat at the magazine, but “Rogues” highlights his obsession with the mechanisms of repression and denial. Like Janet Malcolm, one of his influences, he’s unusually attuned to the self-delusions of both criminals and crusaders.

It can sometimes seem as though Keefe’s interest in a subject is proportional to the reporting difficulties it presents, and his stories hold a particular how-did-he-do-that? fascination for other journalists. A typical Keefe narrative will tend to note the formidable obstacle course that stands in his way. “Steinmetz, who made his name in the diamond trade, hardly ever speaks to the press, and the corporate structures of his various enterprises are so convoluted that it is difficult to assess the extent of his holdings” reads one characteristic setup. For fellow practitioners, part of the pleasure of Keefe’s work comes from watching him ingeniously clear each hurdle without seeming to break a sweat.

Last month, Keefe spoke to me about his reporting strategies and writing process over Zoom from his home in Westchester County, New York. Our conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

“Rogues” spotlights your interest in unearthing the codes that govern sub rosa institutions: Swiss tax havens, American hedge funds, the international arms trade, the Sinaloa cartel. People always ask you where your interest in secrets comes from. If you were to profile yourself, how would you go about answering that question?

Gosh. If someone like me were profiling me, I would run in the opposite direction. [Laughs] I don’t know. My mother is a retired professor of philosophy who wrote books about a series of psychiatric conditions — about madness and multiple personality disorder and melancholy and depression. This idea that we are all strangers to ourselves is an idea that I was probably exposed to growing up because it was a theme that animated a lot of her work. It’s not that I grew up — at least, I don’t think I did — in an environment where I was surrounded by great secrets, but certainly the ways in which truth can be warped in the retelling and the ways in which there are strains of denial in my family, as there are in most families, propels some of this interest.

But there’s no “Rosebud” moment, and that’s funny because I’m often looking for those types of moments with the people I write about. In “Empire of Pain,” there’s one story about Isaac Sackler, the original patriarch, losing everything and telling his children that he’d given them a good name. I remember when I stumbled across that in an interview that Arthur Sackler gave to the student newspaper at Tufts in the ’80s. It wasn’t online, but I got somebody to digitize it, and just discovering that unlocked so much of what I hadn’t been able to understand about him as a person. But listen, if Arthur Sackler were alive and with us, he would probably contest the notion that his whole life could be summed up by that anecdote. There is something reductive about this kind of writing, right?

When you’re finding that key or putting that psychoanalytic pressure on someone’s life, do you ever hear back from subjects who say, “Actually, it wasn’t quite like that?” I’m thinking of your profile of the lawyer Judy Clarke, which is collected in “Rogues.” You write about how it’s not completely obvious what drove her into controversial criminal defense work, representing people like the Unabomber, but you speculate that it might stem from some early family history.

I never heard back from Judy Clarke. I did hear from some people who know her, who felt that it was quite an accurate portrait and a flattering one, I should say. Part of what I like about that piece is that there are people who read it and are uncomfortable about her and the role that she plays and there are others who regard her as very saintly.

It’s awkward. I remember having a conversation with Anthony Bourdain about this. I spent a year working on the profile, and I said something to him about how if any of us were shown a very close-up photo of our own faces in a harsh light — I don’t mean designed to be unflattering, I just mean in a way that wasn’t airbrushed or tweaked — that would make most of us uncomfortable. In a strange way, if a portrait that I’m writing about somebody doesn’t induce a little bit of discomfort in them, I would almost feel that I hadn’t done my job. It would be weird for me to have somebody come back and say: “Thank God, finally, somebody’s captured my true essence as I see myself in the mirror.” I’m not the ventriloquist for the person I’m writing about. There’s always that little bit of dissonance there.

What criteria do you use to decide that a story is going to be worth pursuing, even if you can’t get to that Rosebud or “a-ha!” kind of moment? Has podcasting changed your conception of what counts as a viable story?

I can answer both questions with the same answer. For years, I would bring my editor at The New Yorker, Daniel Zalewski, ideas that were mysteries that I didn’t have the solution to. He always had a view — and he eventually brought me around to this view — that if it’s an 8,000-word magazine article and it’s a mystery story, you pretty much need to solve it. Occasionally there are exceptions, but there’s something about the compact with the reader that if they’re going to devote 45 minutes of their life to reading your piece, and at the end, you throw your hands in the air and say, “We’ll never know,” they feel cheated.

What that has meant for me is that, by and large, I don’t go into stories that are open-ended mysteries if I feel as though I may not be able to crack them. In the case of “Say Nothing,” what was funny was that it was a whodunit, but I never thought of it as a mystery story. I didn’t care who killed Jean McConville, because I always assumed that it was some anonymous IRA gunman, it wasn’t one of my characters, and I had been so ruthless with that book about making sure that the narrative didn’t get too far afield from my central characters. The weirdness of that experience was that it turned out to have been one of my characters all along.

With “Wind of Change,” I did it as a podcast and not as an article because I knew from the start that it would end in an ambiguous place. If it was true, it would be very difficult for me to prove that dead to rights, and if it wasn’t true, it would also be difficult for me to prove that negative. I struggled, because I wanted to write about it, but I didn’t know how to do it in a way that wouldn’t feel indulgent. Then I woke up in the middle of the night one day and thought: “No, it’s a podcast. That’s what it wants to be.” There’s something weird about podcasting where I think there’s more generosity, maybe even more indulgence, from the listener.

You’re strict about what’s included and what’s left out of the frame in “Say Nothing” and “Empire of Pain,” which at times gives the books the feel of chamber dramas. How early in the reporting are you thinking about structure? How big of a part of what’s drawing you to a story is the chance to tell it from a new angle?

When I talk about this stuff, I always want to acknowledge the enormous privilege I have to be doing this work. It’s a huge luxury to be able to spend six or eight months or a year on a piece and to write 10,000 or 12,000 or 15,000 words. When it comes to the reporting, it’s not that I’m driving around in town cars and staying in nice hotels, but it’s basically carte blanche if I need to buy court transcripts, or hire fixers, or go back to France, or go back to Northern Ireland the second time, or whatever it is, and all of that really helps.

What it means is that there sometimes are stories that have been explored in one way or another by newspapers or by other magazines. In terms of the books, sometimes there are other books. There was already a huge literature on the Troubles, obviously, and same with the opioid crisis. So a lot of the time, what’s happening is, I’m coming in, as you say, from a different angle. It’s not that I’m a hugely counterintuitive thinker. It’s much more driven by my own desires as a reader. I had read the other opioid crisis books, and two of them had a few chapters about the Sacklers, and I found, when I was reading them, that I wanted to skip ahead to the next chapters about the Sacklers, which, right there, told me something.

Similarly, with the Troubles. There are a lot of amazing books about the Troubles, but many of them are impenetrable because there’s a highly digressive style of telling stories about the Troubles. You have all these people who are interconnected, so there’s this idea that you can’t tell the story of this person without telling the story of that other person, but then in order to understand them, you need to move to a third person. They’re full of names and acronyms of different armed groups. There’s also this notion that you can’t really understand 1972 without first looking at 1916, but in order to understand 1916, you really need to go back to the 19th century, and suddenly, you’re a thousand years off from where you started. As a reader, I had found that frustrating and forbidding, so I set out to do it a little differently. But it’s more driven by what’s interesting to me than it is by any crafty meta effort to tell a different story.

I want to ask you about openings. Your Bourdain profile, to take an example, starts somewhat left of center stage with a detailed description of President Barack Obama’s motorcade. How do you know when you’ve found your opening?

I often know it when I see it. I’m always thinking about structure, and I’ve gotten better at that over the years having the confidence as I’m reporting to be thinking, “How am I going to tell this story?” To me, an opening is like the top of the water slide. I just need to get you over there and get you going, and hopefully, once I have you there, the rest of it will fall into place.

A lot of the time I’m thinking about trying to upend your expectations. In the case of Bourdain, here was a guy who’d been profiled a thousand times, so it was very important to me to try and start in a place that no other Bourdain profile started before you found your way to him. There’s a wonderful screenwriting expression — the cold open — where you start an episode in a TV show and you’re not with your characters, you’re somewhere else. The back-of-the-mind analytical pleasure for the viewer is: You’ve deposited me in some random place. How are you going to get me back to the main road?

Another example would be the El Chapo story. There’s a certain person who feels like they’ve read drug cartel stories or that they aren’t the kind of person who reads drug cartel stories. There’s a sameness to it all. So when I found this very dramatic moment where an assassin was arrested in Amsterdam at the airport, I knew that was the way in. He wasn’t even a central character, but I thought, if you can see that it’s a story about a Mexican drug cartel but you find yourself in Amsterdam in the first paragraph, I’ll be hopefully overcoming that impulse you have to say, “I’m going to turn the page because I’ve already read this story.” Better yet, maybe I’m putting a question in your mind, which is, “How is Keefe going to get me from Amsterdam back to where I know this story will ultimately unfold, which is Mexico?”

You’ve written screenplays and talked about the influence that screenwriters have had on your work. Has writing in that form changed the kinds of details you report for?

The screenplays I’ve written, none of which have been made — I’m a terrible screenwriter — I don’t know if they’ve actually changed my reporting much. There’s a schlocky journalism that aspires to be a screenplay — and I think a lot of the time is aspiring for a Hollywood option — that I really hate. I have an allergy to a certain “We open on...” writing that is striving for the adjective “cinematic.” Even just using that adjective, I feel, gives short shrift to good narrative nonfiction. As much as I can, I always want you to be able to see things in your mind’s eye. I want to know what things smell like. I want to know how things sound. But none of that is the screenwriting. The sense in which screenwriting has been helpful has much more to do with transitions: when you get into a scene, when you get out of a scene and how you juxtapose scenes. There’s a kind of economy to the structure of a screenplay that I have found really helpful.

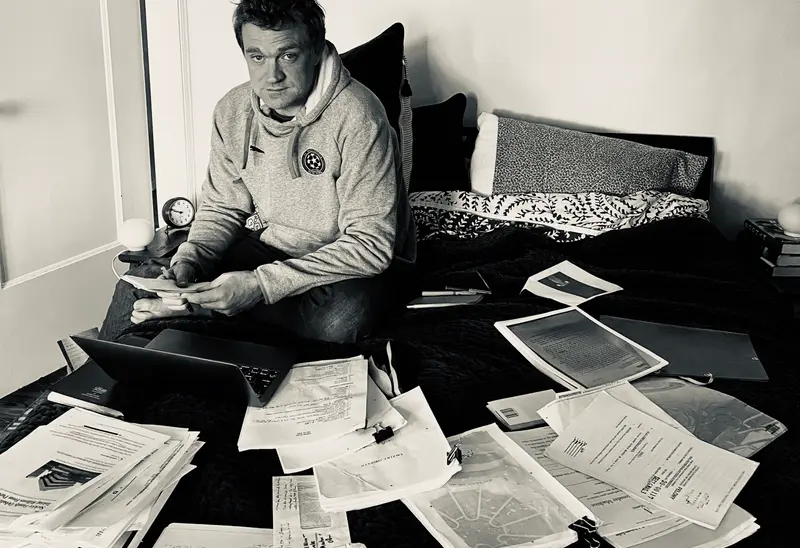

How do you organize and outline all of the materials you gather as you’re reporting?

It’s always the same: It starts with a series of big beats. If it’s an article, it starts with eight beats on the back of an envelope, so I’ll know where the piece starts, I’ll know where I want the transition after the first section to be, and even if I’m feeling my way, I’ll know where the big moments are later on. The reason it’s useful to do the outline on the back of an envelope is that I naturally gravitate to complicated stories — and I like the complication — but I think you need to back away from that and be able to see the topography of the story.

Then, as I’m reporting, I’m filling those beats in with more detail along the way, and I’m always trying to find ways to fold in exposition so that, hopefully, you don’t notice it. That’s something I’m pretty fanatical about. One thing I really dislike is the paragraph break or the chapter break, where it’s like, “Now, 5,000 words of exposition.”

As I’m filling it in, I try to get to the point where when I sit down to write, all the ingredients are there. I think of it like a chef with his mise en place. Of course, when I cook, I never do this, but people who are cooking the way they’re supposed to will have all their ingredients measured out and ready before they start preparing the meal. The way I like to feel with writing is that I don’t have to go digging around in a notebook, because it’s all right there, laid out in roughly the right place, so that all I’m doing is coming in and putting the finishing work on something that is already pretty well-populated.

A lot of your stories are write-arounds, where you lack direct access to your main subject. You’ve said that you’ll often request an interview early on and that if you’re rebuffed, you’ll remind the subject before publication that the train is leaving the station: The story will happen with or without their cooperation. But the story can’t really happen — or can’t be as successful — without the cooperation of your subject’s close friends or former associates. How do you make that pitch to the people in their orbit?

It totally varies from story to story. I have the advantage of spending months and months and months working on these pieces, and I’ll often interview 25, 40, 60 people for a piece. The advantage of that is that sometimes people will say “no” initially and then they just keep getting emails from people they know saying, “Oh, I just talked to that reporter.” Or, when I make a second overture, I’ll say, “Oh, I just talked to this person and this person,” and so sometimes people do come around, even the central people, but it really varies.

In the reporting phase, I try to be compassionate and to meet people where they live. I don’t usually come in with a big agenda, which is not to say that I don’t form judgments, but that all happens later in the writing phase. I’m pretty bloodless in the writing phase, but in the reporting, I want to be open. It’s helpful if I can interview somebody for two hours and they really get a sense of the cut of my jib: they know the kinds of questions I’m asking, they get a sense of the other people I’ve talked to and then they can report back to the subject. I think the fear that people often have is, “Oh, this is going to be a hatchet job.” But the truth is if you interview somebody for two hours and you really get into the nitty-gritty, they can usually see that you’re going to approach the story responsibly.

In terms of the case that I make, I always say: “I’m going to do the work. I’ll keep coming back. I’ll talk to as many people as possible.” Sometimes that backfires. What I said to Gerry Adams’ people was something like: “Nobody works harder than me. I’ll get to the bottom of everything,” and in retrospect, I realized that was not what they wanted to hear at all. [Laughs] When I said that, they said, “OK, well, we won’t be talking to you.” But I think most of the time you’re just earnestly telling people that you want to understand.