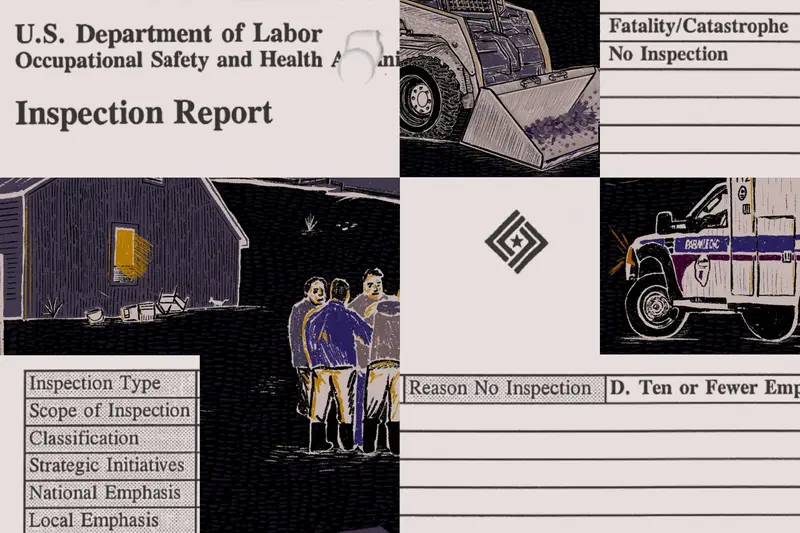

When dairy workers die on farms across the country, the circumstances are often similar: They drown in manure lagoons, get crushed by skid steers, are trampled by cows.

But whether the government investigates their deaths depends on factors that advocates for worker safety say seem arbitrary: the state where they died, the size of the farm where they worked or whether they lived in employer-provided housing.

For decades, Congress has banned the federal Occupational Safety and Health Administration from investigating worker deaths, injuries and complaints on farms with fewer than 11 workers unless those farms have employer-provided housing known as a temporary labor camp. How this exemption for small farms plays out looks different in the country’s dairy states.

In New York and Vermont, for instance, worker advocates say they don’t bother calling OSHA when workers die or get hurt on small farms because they’re so used to the agency saying it can’t investigate.

In Wisconsin, OSHA has sometimes investigated dairy worker deaths on small farms when those farms provide housing to immigrant workers. In such cases, the agency has called that housing a temporary labor camp that gives it jurisdiction to inspect.

And in California, which has a more robust occupational safety and health plan than the federal program, inspectors look into dairy workers’ deaths and injuries no matter how many workers a farm employs. The question of whether there’s worker housing is irrelevant.

This patchwork of enforcement, in which some deaths are investigated and others are ignored, is fundamentally unfair, advocates say.

“It’s unjust and it’s inhumane,” said Crispin Hernández, a former dairy worker and a member of the Workers’ Center of Central New York, a nonprofit focused on workplace and economic justice. “It is on small farms that workers get injured the most.”

Last month, ProPublica reported on how OSHA has inconsistently labeled farm housing for immigrant dairy workers in Wisconsin as a temporary labor camp. Our reporting identified three worker deaths on small farms over the past decade, including the March drowning of an undocumented Mexican immigrant in a manure lagoon, that OSHA said it couldn’t investigate even though workers lived in farm housing.

OSHA officials declined interview requests but have said the agency has a consistent national policy on how it views temporary labor camps.

Since 2005, OSHA offices said they couldn’t investigate 44 safety incidents on dairy farms — including deaths, injuries, complaints and referrals from local agencies such as medical examiner’s offices — because of the small-farms exemption, records show. It’s unknown how many of those farms provided housing to immigrant workers, something common on dairy farms across the country.

None of this is as clear cut as many advocates and farmers would like, and the issue has received scant attention. More than a dozen farm safety advocates, farm worker attorneys and dairy worker researchers from a number of states — including Wisconsin — told us they had no idea it was even possible for OSHA to look into deaths and injuries on small dairy farms that provided housing to immigrant workers.

“We end up in these granular arguments over what counts as temporary or seasonal or what’s a labor camp,” said Hannah Gordon, an attorney with the Farmworker Law Project of the Legal Aid Society of Mid-New York.

One of the key factors in OSHA’s approach to deciding if a dairy farm has a temporary labor camp is whether it considers the workers themselves to be temporary or permanent. The answer is not immediately obvious because cows are milked year-round. Agricultural jobs such as picking apples or blueberries are more clearly seasonal.

In addition, dairy farms can’t use a federal guest worker program to bring in immigrants on temporary visas. Instead, the industry by and large relies on undocumented immigrant workers whose ability to stay permanently in this country — and, by that logic, stay permanently on a job — is precarious.

“Being undocumented and constantly facing the risk of deportation” is one reason these workers could be considered temporary, said Maggie Gray, an associate professor of political science at Adelphi University who studies New York farm workers. “They have permanent homes in their home country where they intend to return.”

OSHA doesn’t ask workers whether they’re in the U.S. legally. But in Wisconsin, OSHA inspectors have described some immigrant workers who live on dairy farms as temporary workers because they are hired with the understanding that they may go back and forth to their home countries to visit their families.

The prospect of OSHA taking a similar view of dairy workers in New York — where an estimated 80% live and work on small farms — led to pushback from a group of seven members of Congress from that state in late 2013.

At the time, OSHA was preparing to launch a program to improve safety on New York’s dairy farms. The program would allow the agency to conduct random inspections, something it typically doesn’t do.

But the representatives wrote to OSHA’s top official, asking for it to be delayed and to discourage the agency from considering immigrant dairy workers as temporary when deciding whether a small farm was eligible for inspections.

“A dairy farmer hires an employee with the understanding and intent that the employee will be here long term,” the lawmakers wrote. “A dairy farm employer does not embrace the cultural assumption that an employee of a foreign ethnicity or whose primary language is not English is seeking work as a temporary or seasonal worker when they accept a permanent position on a farm.”

OSHA conceded the point. David Michaels, then the assistant secretary of labor for OSHA, wrote back to the lawmakers and said the agency had decided to limit the scope of the program to “dairy farms with eleven or more employees, so the definition of temporary labor camp is no longer relevant.”

Outside of the New York effort, Michaels wrote, the agency would not inspect small farms that provided housing to their workers if the employers had offered them permanent jobs.

In a recent interview, Michaels said he did not recall the controversy around temporary labor camps. He also said he wasn’t aware that OSHA officials in Wisconsin had concluded that housing for immigrant workers on dairy farms was a temporary labor camp so they could investigate deaths on small farms.

But he said he was “glad to hear that” and thought that the agency’s work in Wisconsin should be more widely known. That way, he said, perhaps more advocates would call OSHA when workers die or get injured “in situations where OSHA could actually answer.”

Erica Sweitzer-Beckman, an attorney and the legal director of the Farmworker Project at the nonprofit Legal Action of Wisconsin, said that when a farm “asserts an exemption, OSHA could thoroughly investigate to determine if the exemption actually applies.”

Not every state relies on federal OSHA; more than 20 states have their own safety and health workplace programs. At least three of those states, California, Oregon and Washington, use state funds to inspect farms of all sizes, regardless of whether there’s housing for workers.

“There is no small-employer exception,” said Garrett Brown, a retired field compliance officer and senior official with the California Division of Occupational Safety and Health. “If you have one employee, that’s it; you’re an employer and you fall under Cal/OSHA’s jurisdiction the same as United Airlines or Coca-Cola.”

Some research has shown that the fatality rate for farm workers is significantly lower in California, Oregon and Washington than in states where the small-farms exemption is observed. Dairy farms on the West Coast tend to be larger operations than those in the Midwest and East Coast, and there are far fewer of them, which may also contribute to the difference in fatality rates. California is the nation’s biggest dairy producer. Wisconsin ranks second; New York is fifth.

Matthew Keifer, an occupational medicine physician and researcher who lives in Washington state and previously ran the National Farm Medicine Center in Wisconsin, said small farms in states that rely on federal OSHA don’t always put a priority on safety issues because they know “they’re not likely to be investigated, fined or found culpable if someone is seriously injured.”

He added that in Washington, by contrast, “there is a healthy preoccupation about the possibility of being inspected.”

Other states, including Vermont, have state OSHA plans that mirror the federal OSHA when it comes to the small-farms exemption. Vermont hasn’t considered employer-provided housing for dairy workers a temporary labor camp.

In December 2009, a worker named José Obeth Santiz Cruz died on a small Vermont dairy farm after he was pulled into a piece of machinery and strangled by his own clothing. The state OSHA sent two inspectors to the farm. Santiz, an immigrant from Mexico, lived in farm housing, according to interviews and records.

But the agency determined it couldn’t investigate because the farm employed too few workers.

In an email to ProPublica, Dirk Anderson, the director of the Vermont OSHA, said his general understanding was that dairy work was not “of a seasonal or temporary nature.” However, he said, “it is certainly something I will discuss with both our legal counsel and my commissioner in the near future.”

Santiz’s death helped lead to the creation of Migrant Justice, a dairy worker-led human rights organization in Vermont. Marita Canedo, the group’s program coordinator, said nearly all of the 1,000 or so immigrant dairy workers in the state live on the farms where they work.

Canedo and her colleagues routinely hear about workers who get hurt on the job. But they rarely call the state agency for a number of reasons, including its hands-off approach to small farms. Recently, when a worker lost several toes after the heavy metal bucket of a skid steer crushed them, Canedo said she didn’t bother to contact OSHA.

“We don’t even think about OSHA,” she said.

Mariam Elba contributed research.