This article was produced in partnership with Oregon Public Broadcasting and The Oregonian/OregonLive. You can sign up for The Oregonian/OregonLive special projects newsletter and Oregon Public Broadcasting’s newsletter. Oregon Public Broadcasting is a member of the ProPublica Local Reporting Network.

With the Oregon Legislature taking up bills to overhaul or eliminate the Oregon Forest Resources Institute after a news investigation last August, lobbyists have repeatedly attacked the reporting as incorrect.

The institute is a quasi-governmental agency meant to promote forestry education. The joint investigation by The Oregonian/OregonLive, Oregon Public Broadcasting and ProPublica found that the institute had acted as a de facto lobbying arm of the timber industry, in some cases skirting legal constraints that forbid it from doing so.

At a hearing last Tuesday, a timber lobbyist set aside his prepared remarks and told lawmakers that the investigation was “full of half-truths,” “absolutely inaccurate” and “completely bogus.”

The lobbyist, Jim James, representing the Oregon Small Woodlands Association, told lawmakers we “took a segment of an email, interpreted it for [ourselves] ... and came up with some conclusions that were absolutely inaccurate.”

James, who did not respond to emails seeking comment, expanded on his criticism in written testimony, telling lawmakers, “This so-called news is full of half truths that the authors chose to, without justification, put a biased slant on the information they had collected. To suggest they know everything about OFRI from emails and their own interpretation of the emails is absurd.”

That’s not what we did. And below we’ll share the emails so readers can see for themselves.

We provided the emails we cited in our investigation to the people who wrote them. We asked detailed questions. When their responses weren’t clear, we asked them to clarify. This is how journalism works.

The investigation was based on a year of reporting, including interviews with more than 20 people inside and outside the institute, as well as a review of tens of thousands of pages of emails, budgets, publications and other institute records that we obtained under Oregon’s public records law.

James told lawmakers he didn’t understand why the media and others “hate the wood products industry and anything associated with it. It is obvious the media works diligently to exaggerate everything it can to disadvantage the wood products industry.”

A lobbyist for the industry’s main state trade association, the Oregon Forest & Industries Council, made similar claims in a message rallying supporters to testify. “Many, if not all, of the allegations made in the Oregonian/OPB/ProPublica article are false, half-truths, or the information was misconstrued in a way to cast OFRI in a negative light,” wrote the lobbyist, Sara Duncan.

Asked repeatedly for specific examples, Duncan told reporters in a March 5 email: “There is not nearly enough time, nor do I have interest, nor do I think it would be productive to spend my day going line by line identifying mischaracterizations and sensational over-blown conclusions with those who hold the pen.”

In her message to the institute’s supporters, Duncan said one of our “primary assertions” was an incorrect description of the institute as “taxpayer funded.” James also repeated the claim in his testimony.

Our investigation said the institute is “tax-funded” because it is. The institute’s $4 million annual budget comes from a tax on logging.

Without providing evidence, lobbyists said we twisted the truth. We didn’t. Here are the investigation’s major findings. And the receipts.

The Institute Attacked Climate Scientists

In 2018, the institute led a coordinated industry effort to undermine two Oregon State University scientists whose research found that logging, once thought to have no negative effect on global warming, was one of the biggest sources of climate pollution in the state.

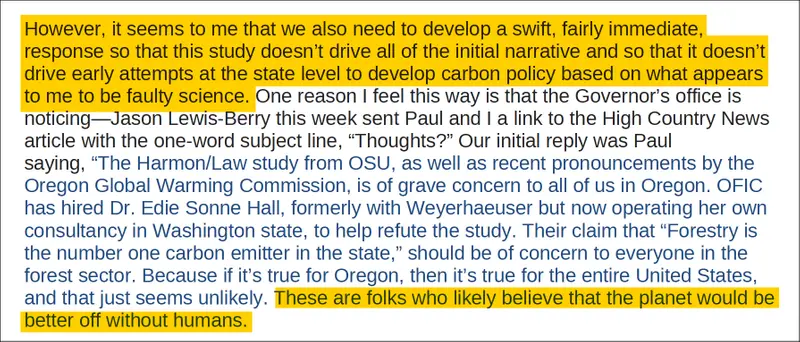

OFRI’s leader at the time, Paul Barnum, told lobbyists in an email that the research was “of grave concern to all of us in Oregon.” He protested one researcher’s planned radio appearance to her dean and suggested the dean should commission an independent review of the study.

“These are folks who likely believe that the planet would be better off without humans,” Barnum wrote of the researchers in one May 2018 email.

Another OFRI employee, Timm Locke, offered to help a timber lobbyist draft a counterargument that “those of us in the industry can use.” Locke told us in an interview that the line between lobbying and educating at the institute was unclear. He said his pushback against the study wasn’t an attempt to sway state policy, but rather to make sure policy was based on sound information.

Barnum, who retired as executive director in 2018 but continued working under contract through June 2020, said it was not wrong for him to question the Oregon State University study or other academic research. But he acknowledged that he’d made inappropriate comments, including those that questioned the researchers’ motives.

In testimony submitted to lawmakers last week, Barnum said he took the press coverage “very seriously.”

“But let’s be honest,” he wrote. “If the Legislature eliminated every state agency and department criticized by the Oregonian, there would be far fewer state agencies.”

The Institute Attacked Other Forestry Researchers and Professors

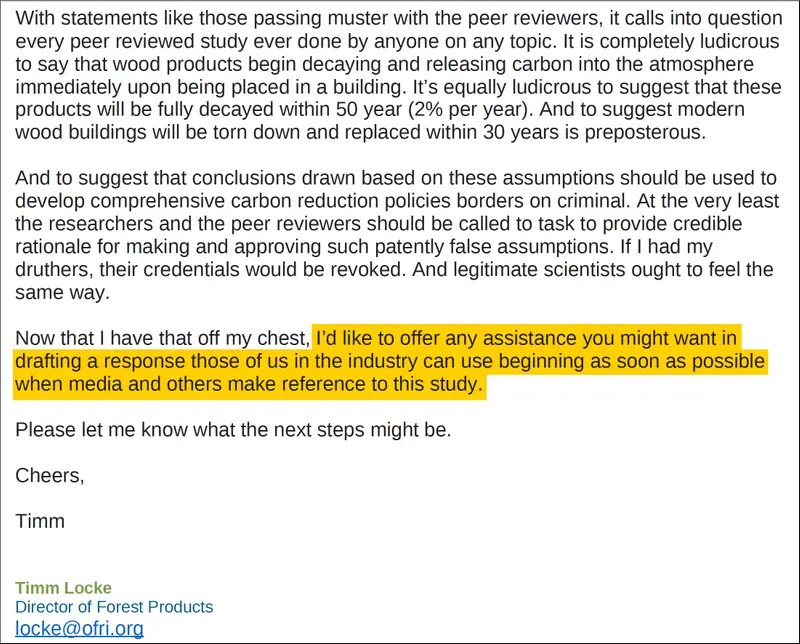

OFRI tried to undercut an Oregon State researcher who planned to survey public perception of spraying herbicides in private forests, a project that Barnum in 2017 called “fairly dangerous.”

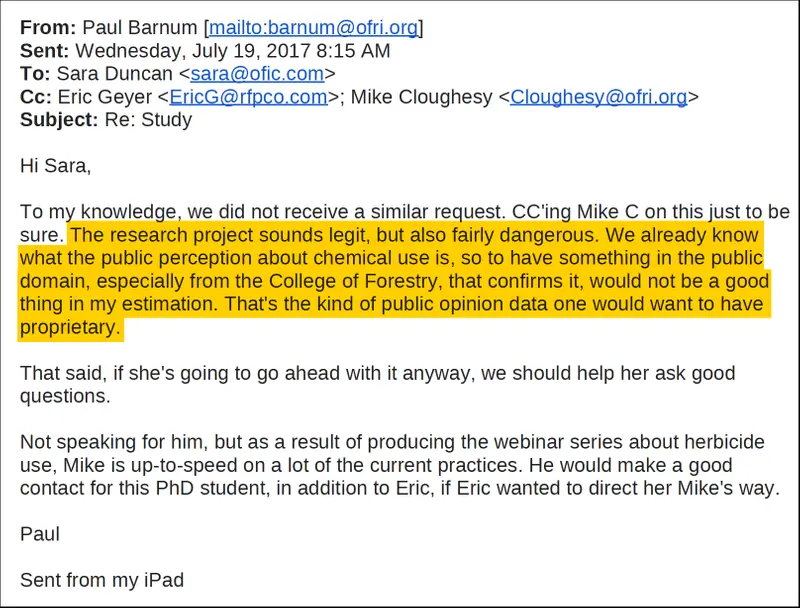

Timber companies raised concerns with OFRI in 2019 after the survey resurfaced and included questions about whether residents trusted private timber companies to provide truthful information about spraying herbicides used to kill vegetation that sprouts in the bare earth of clear-cuts. The survey asked respondents whether they would vote for or against aerial spraying if the issue appeared on the ballot.

OFRI’s current director, Erin Isselmann, challenged the validity of the researcher’s project with his dean. She suggested in an email to a timber executive that the institute could prepare for the results by spending $60,000 on its own study. She told us she wasn’t attacking science, she just wanted to learn more about the survey. Isselmann, who has been the institute’s executive director since July 2018, said she has operated “under the highest ethical standards.”

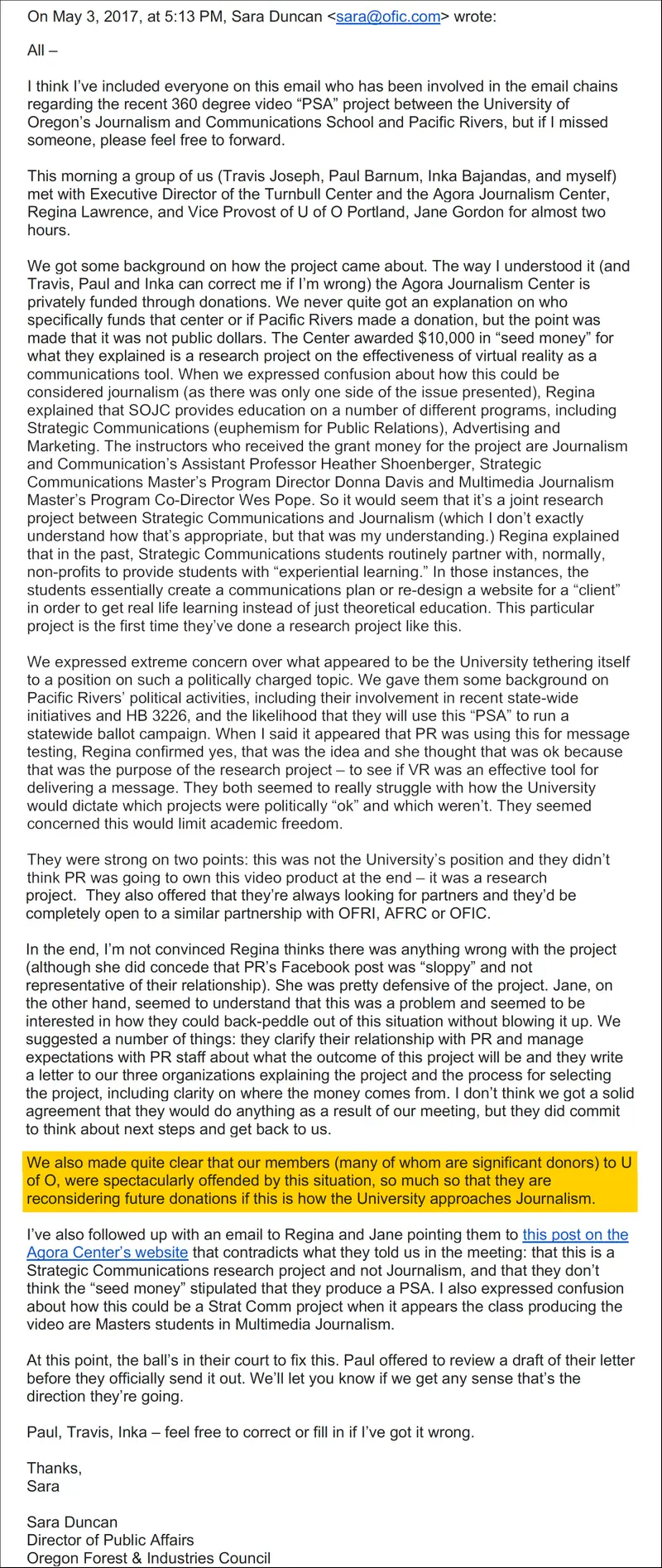

In 2017, the institute’s then-leader, Barnum, joined industry lobbyists in targeting a University of Oregon journalism professor who produced a video that criticized logging as part of a research project.

Barnum and the lobbyists met with school officials and threatened to pull donor funding. Here’s an industry lobbyist’s summary of that day.

Despite Prohibitions Against Lobbying, OFRI Kept Tabs on Politicians, Legislation and Ballot Measures

In 2018, OFRI’s outgoing and incoming executive directors sat through private industry deliberations about political attack ads that opposed Oregon Gov. Kate Brown’s reelection that year. And in 2019, its board discussed rushing a report in an attempt to stop ballot measures that targeted logging, the news organizations found.

Barnum later said they should not have stayed in the private meeting; Isselmann noted that it happened during her first week on the job. The board member who suggested rushing the report, Casey Roscoe, whose company gave more than $100,000 to the industry campaign against the measures, said she wanted both sides to have the best information available.

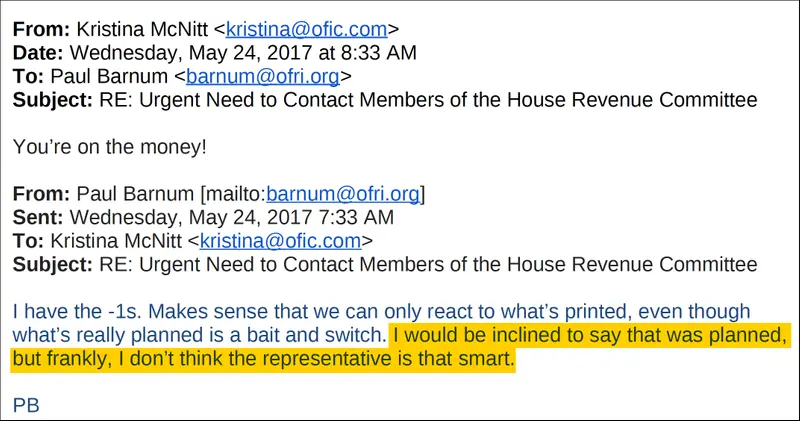

Wondering whether a 2017 bill amendment that meant to target the institute was a bait-and-switch, Barnum said of Rep. Paul Holvey, who introduced it, “I don’t think the representative is that smart.”

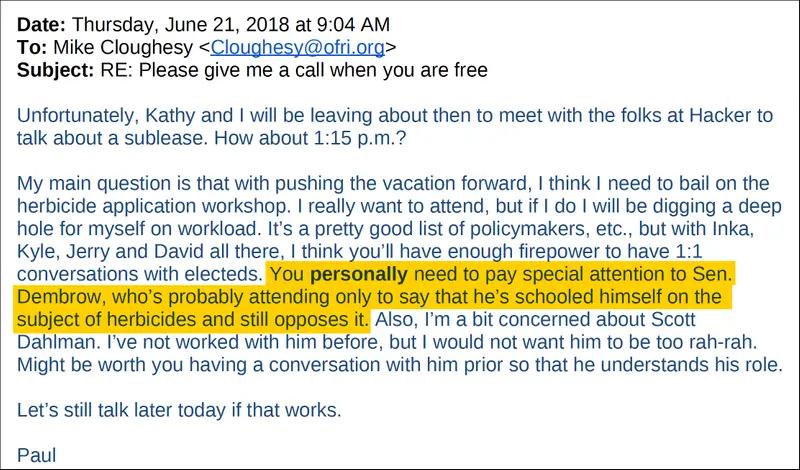

And when state Sen. Michael Dembrow registered for a tour OFRI helped organize, Barnum told a staffer to keep his eye on Dembrow, a Portland Democrat who’d tried to tighten spraying laws.

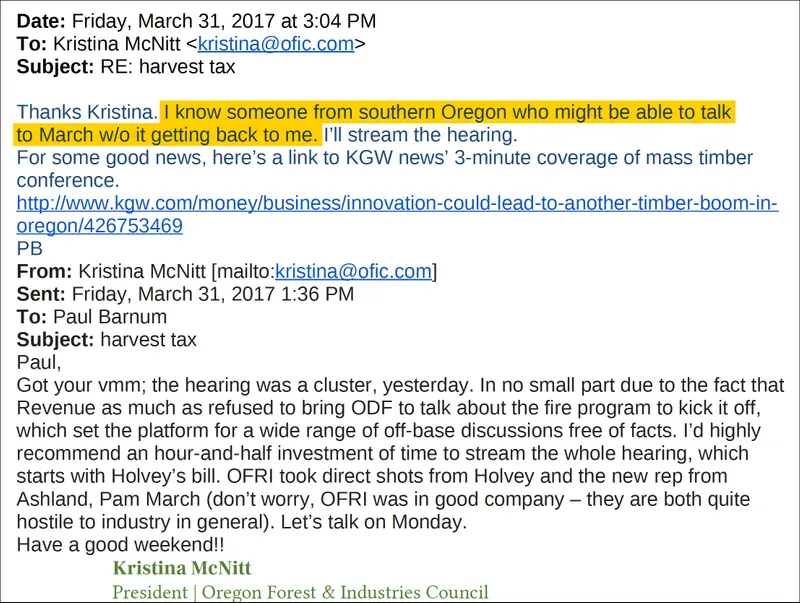

After Rep. Pam Marsh, an Ashland Democrat, questioned whether the institute’s funding should be cut during a 2017 hearing, Barnum told a lobbyist: “I know someone from southern Oregon who might be able to talk to March w/o it getting back to me.”

Barnum acknowledged in an interview that he had made inappropriate comments about legislators.

Highlights added by ProPublica.