This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with THE CITY. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

It was almost time for school pickup when Paul’s mom saw the text on the classroom messaging app: Paul — her 7-year-old — “ended up running out of class today and it escalated rather quickly.” Someone at the school had called 911. Paul’s parents could contact the main office for more information, the message read.

Paul’s mom remembers the physical feeling of dread, like ice under her skin. Paul — that’s his middle name — has a neurological disorder. He loves to cuddle with his mom and help take care of his baby sister, and he’s wild about Greek mythology. Like a lot of kids with developmental disabilities, he also has very big tantrums, hitting, spitting and throwing things when he gets upset. Since the end of first grade, he’s been in a special public school classroom in Brooklyn that integrates disabled and nondisabled kids.

The day of the message, in early December, Paul’s mom was so panicked that she couldn’t fully make sense of what it said. Why had the school called 911 instead of calling her? Was her child hurt? Had something gone terribly wrong? She wanted to run the last few blocks to the school, but her legs felt frozen. It was hard just to walk.

When she made it into the school building, she found Paul lying facedown on the floor of a computer room, his whole body heaving with sobs. She touched his back, and he screamed and tried to scramble away. Then he recognized his mother’s voice and jumped into her arms. “Mommy, don’t let them handcuff me,” he begged.

“I said, ‘What are you talking about? No one is going to handcuff you.’”

But that’s when she found out: Someone already had.

That afternoon, Paul had had a meltdown that started in his classroom and spilled into a hallway. When he didn’t calm down, someone called a school safety agent — an officer of the New York Police Department who is stationed full-time in the building. Paul knocked off the agent’s face mask and glasses, and that’s when it happened. The agent pulled out a pair of Velcro restraints and forced them over Paul’s hands.

Looking now, Paul’s mom could see red marks where the handcuffs had rubbed Paul’s wrists raw. But she felt more bewildered than ever. She must be misunderstanding, she thought. Who would handcuff a 7-year-old?

New York City officials have promised for years to stop relying on police to respond to students in emotional crisis. Under the terms of a 2014 legal settlement, schools are only supposed to call 911 in the most extreme situations, when kids pose an “imminent and substantial risk of serious injury” to themselves or others.

And yet an investigation by THE CITY and ProPublica found that city schools continue to call on safety agents and other police officers to manage students in distress thousands of times each year — incidents the NYPD calls “child in crisis” interventions. Unless a parent arrives in time to intercede, cops hand kids off to EMTs, who take students to hospital emergency rooms for psychiatric evaluations. In close to 1,370 incidents since 2017, students ended up in handcuffs while they waited for an ambulance to arrive, according to NYPD data. In several incidents, those kids were 5 or 6 years old.

Ten years ago, in the runup to the 2014 settlement, a group of parents sued the city’s Department of Education, claiming that schools violated their children’s constitutional rights and broke federal law by sending them to hospitals when they weren’t experiencing medical emergencies — in many cases in response to behavior that resulted directly from a student’s disability.

The experience was traumatic and humiliating for the kids, the plaintiffs claimed. Students were terrified to return to school; 6- and 7-year-olds thought they were being arrested. Two schools filed child welfare reports on parents who didn’t allow EMTs to put their children in ambulances.

Meanwhile, the hospital visits served no useful purpose, plaintiffs claimed. Students missed crucial class time only to wait for hours in emergency rooms — sometimes with seriously mentally ill adults — and then be sent home. At least one parent lost her job because she was repeatedly forced to leave work to rush to the hospital, and then she was stuck with bills for ambulance trips and ER services her child didn’t need.

As part of the 2014 settlement, the department issued a regulation that requires schools to make every effort to safely manage students in distress without involving police — including by deploying trained crisis response teams and allowing parents to speak to their children by phone if possible. Schools are never allowed to use 911 calls as a punishment for misbehavior. When cops do get involved, they must use the “minimum level of restraint necessary.”

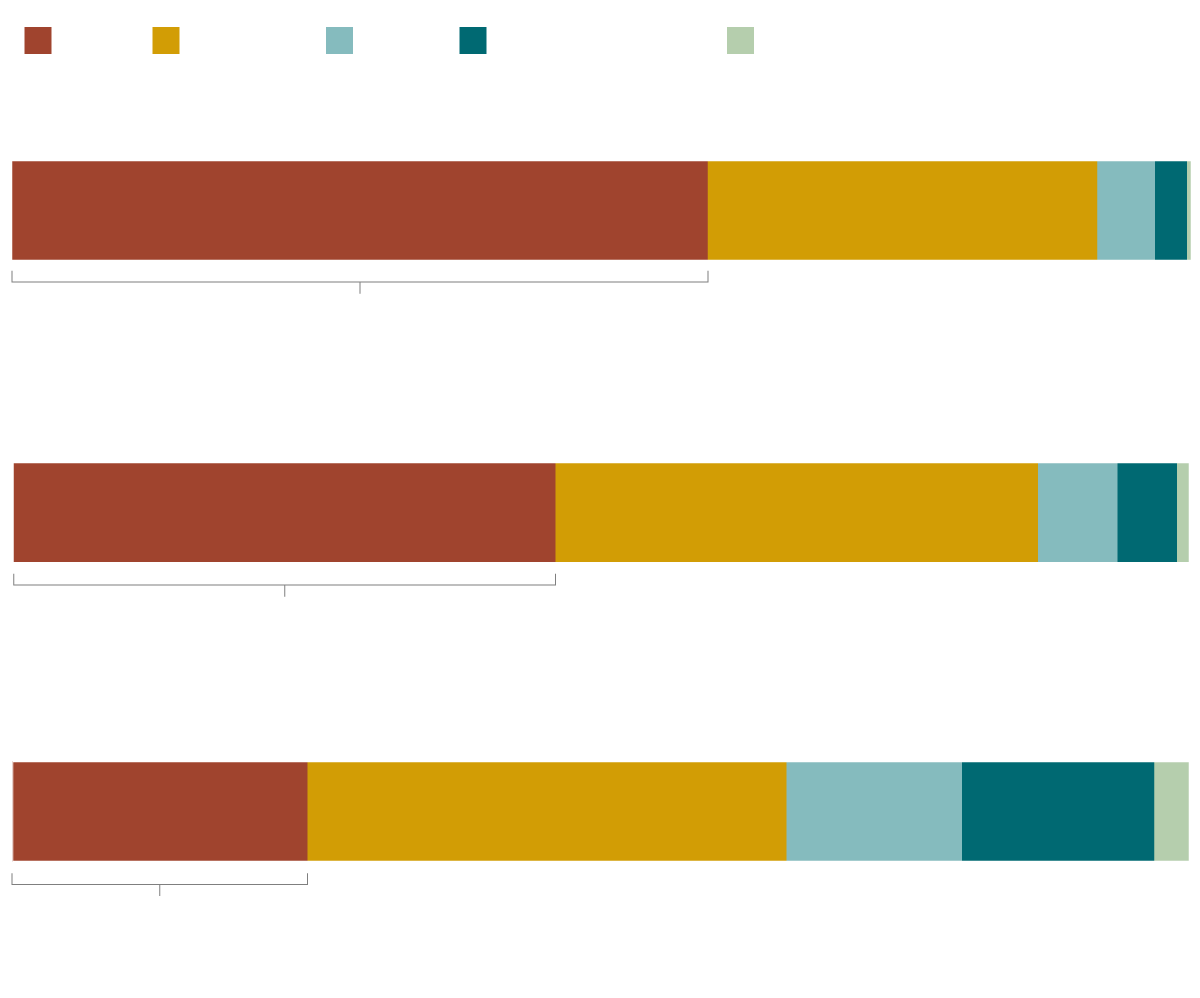

Despite the promises and regulations, New York City public schools call 911 on students in emotional distress as often as ever, an analysis by THE CITY and ProPublica of NYPD data shows. Prior to the lawsuit, city-run and charter schools saw an average of 3,000 child-in-crisis incidents per year from 2005 to 2010 and an average of 3,300 incidents in the 2010-11 and 2011-12 school years, according to court documents. Since 2017 — the first post-lawsuit year for which the NYPD reported complete data — schools have seen an average of 3,200 incidents per year. (The analysis excludes 911 calls made in 2020 and 2021, when schools operated on a remote or hybrid schedule due to the COVID-19 pandemic.)

Schools are far more likely to call 911 on Black students, who make up less than a quarter of the student body but account for nearly half of child-in-crisis incidents and 59% of instances in which students were handcuffed since 2017, the analysis shows. And schools continue to call police to respond to young children: Last year, more than 560 child-in-crisis incidents involved students aged 10 or younger. In five cases, the kids were 4 years old.

“The things that needed to change did not change,” said Nelson Mar, an education attorney at Legal Services NYC who represented the plaintiffs in the 2013 lawsuit.

That’s partly because the Department of Education fails to hold schools accountable for not following its own regulations, Mar and other advocates said. Schools are required to file occurrence reports after calling 911 on students, but they don’t have to show that they took the mandatory steps to manage a crisis first. Unless parents have a lawyer or a paid advocate, they rarely know the reports exist, much less get the opportunity to contest a school’s account of an incident or to object if they believe school staff called 911 to punish a student they were fed up with.

In an emailed statement, Department of Education spokesperson Nathaniel Styer wrote that, if parents believe a school called 911 in violation of city rules, they should contact their school district’s superintendent, who oversees school leaders and can provide additional training. “Situations where young children are in crisis and/or are at risk of harming themselves or others are among the most difficult for our educators and school staff,” Styer wrote.

“Nevertheless,” Styer continued, “whenever there is evidence the policy hasn’t been followed, it will be reported and investigated, and we review every case where 911 is called to ensure that it was necessary and complied with our policy.”

But thousands of children are still being forcibly removed from schools each year, which means the oversight clearly isn’t working, said Amber Decker, a public school parent who was a plaintiff in the 2013 lawsuit and now works as an advocate for parents of kids with disabilities.

If schools were being held accountable for unnecessary 911 calls, “the numbers would have gone down,” Decker said. As it is, “there’s no consequences other than the ones you push for until you’re blue in the face or banging your head against the wall.”

To understand why police are so involved in New York City schools, you have to look back to the late 1990s. Rudy Giuliani was mayor, and schools were at the junction of two of his biggest campaign promises: to slash crime and to fix the education system. For students, that meant a “zero tolerance” approach to school misconduct.

In 1998, the city created a new division of the NYPD, transferring school safety operations — which had previously been managed by the Board of Education — to the police department. Agents were allowed to arrest students for all kinds of misbehavior, including spitting, talking back to teachers and cutting class.

Eighteen years and two administrations later, then-Mayor Bill de Blasio presided over a city that approached young people and police very differently. According to a 2016 mayoral task force that included the commanding officer of the NYPD’s School Safety Division, overly punitive practices weren’t making students safer; they were pushing vulnerable kids out of schools and into the juvenile justice system.

The task force pointed to child-in-crisis incidents as part of the problem. “With little mental health experience or training, and scant access to mental health professionals, ER overuse is the norm,” the task force wrote.

De Blasio promised to transform the city’s approach to school discipline by reducing the role of police and dramatically increasing the mental health resources available to students and teachers. “We’re revolutionizing our school system,” he said in 2019.

The revolution never materialized. In 2021, after New York City students experienced some of the longest school shutdowns in the country, the city hired 500 new school-based social workers to help respond to trauma connected to the COVID-19 pandemic. De Blasio’s was “one of the first administrations to recognize that schools are where kids with mental health problems land,” said Peter Ragone, a longtime de Blasio adviser.

But while the hiring push put the city ahead of many other jurisdictions, New York City schools still have just one social worker for every 475 students — close to double the National Association of Social Workers’ recommended ratio of 250 students per social worker.

The city’s current mayor, Eric Adams, announced a sweeping mental health plan in March that includes a “Mental Health Continuum,” a project that was conceived under de Blasio and rolled out last year to connect schools directly to mental health clinics and mobile crisis teams. But Adams’s proposed city budget, released a month later, included no funding for the project.

“It’s mind-boggling,” said Dawn Yuster, who directs the School Justice Project at the group Advocates for Children. “This would expedite care for young people with the most significant needs. If you’re going to say it, fund it.”

The mayor’s office did not respond to questions about the Mental Health Continuum, but Patrick Gallahue, press secretary for the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, wrote in an emailed statement that a new teletherapy program for high schoolers will “connect even more young people with services by reaching them where they are.”

Meanwhile, in 2022, City Council members acknowledged the need for more oversight of child-in-crisis incidents, introducing a bill that would have required school safety agents to document that school staff tried to de-escalate a crisis before involving police. But the bill never made it out of committee. (Neither Councilmember Diana Ayala nor Councilmember Rita Joseph, both of whom sponsored the bill, responded to requests for comment.)

When school staff don’t get the support they need from mental health experts, they often resort to punishing kids for behaviors they can’t control, Yuster said. It might start with “calling parents every day about a student’s behavior. Then they up the ante, calling to say, ‘We’re suspending for five days, and next time we’re going to call EMS if this behavior continues.’”

Not only do the escalating punishments violate city rules but they also destroy trust between students and schools, said Crystal Baker-Burr, an attorney who directs the Education Project at The Bronx Defenders, a nonprofit public defense agency.

“Even if a school is at their wit’s end,” Baker-Burr said, “sending a student to the ER is not going to help the situation. Getting police involved, handcuffing them, it doesn’t make anything better at school the next day.”

Three years ago, Baker-Burr saw the impact of 911 calls up close — on her 7-year-old nephew, Ethan. (Ethan’s family asked us to identify him by just his first name.)

In 2019, Ethan was a second grader at P.S. 157 in the Bronx. He was a gentle and sweet kid at home, but he got overwhelmed and acted out at school, said his mom, Jacqueline De Jesus. He’d hit other kids or run out of the classroom. Sometimes he’d bite himself. This was before he was diagnosed with autism, and his parents were still trying to figure out what to do. De Jesus asked the school for help, she said, but teachers told her that Ethan didn’t need to be evaluated for educational services because his schoolwork was at grade level.

Instead, De Jesus said, Ethan, who’s Black and Latino, got punished. Teachers yelled at him and sent him out of the classroom. He wasn’t allowed to join music or sports clubs or sign up for the after-school program. The school constantly called his parents to pick him up early.

De Jesus felt like the message was clear. “They didn’t want to deal with him,” she said. It seemed like the school was making it as difficult as possible for Ethan to stay.

P.S. 157’s principal did not respond to a request for comment. The Department of Education declined to comment on Ethan’s experience, even though De Jesus signed a release allowing it to share information with THE CITY and ProPublica.

In April 2019, De Jesus got a phone call that shocked her. It was the school secretary, saying that an ambulance was on its way to take Ethan to the hospital. De Jesus was at work in Manhattan — a 40-minute cab ride away — so she called Baker-Burr, who went straight to the school. When she got there, Ethan was curled up in a ball underneath a desk, rocking back and forth and sobbing. His face was swollen and red from crying for so long.

Two uniformed police officers were “standing over my very small nephew,” Baker-Burr said. “They were saying things like, ‘Don’t lie to us, Ethan. When you’re older, we could arrest you for things like this.’”

Baker-Burr asked the officers to leave the room, then got down on the floor and convinced Ethan to come out from under the desk, promising that she wouldn’t let anyone hurt him. By the time the ambulance arrived, he was calm, talking to Baker-Burr about his new Five Nights at Freddy’s backpack. Baker-Burr rode with him to Lincoln Medical Center, a public hospital in the South Bronx, where a doctor interviewed him and sent him home with a note saying he was fine to return to school.

“They were like, ‘Why is this child even here?’ It was a colossal waste of time,” Baker-Burr said.

That didn’t stop the school from calling 911 on Ethan two more times in the next month, De Jesus and Baker-Burr said. Nor did it prevent De Jesus from being billed hundreds of dollars for ambulance rides and ER visits.

Eventually, De Jesus gave up and petitioned the city to move Ethan to a different school. “I didn’t want to send him somewhere he wasn’t wanted,” she said.

Calling 911 on kids “is the last thing any teacher wants to do,” said Kristen GoldMansour, a former teacher and coach who works with dozens of New York City schools to support inclusive programming for students with disabilities.

“The question is, how did we get there?” GoldMansour said. “There’s probably a thousand million things we could have done to avoid getting to that point.”

In fact, when students’ behavior or mental health needs get in the way of learning, federal law requires schools to intervene, proactively offering them evaluations and services like occupational therapy or a functional behavioral assessment — a detailed analysis of what triggers kids’ behaviors and the best strategies to prevent an emergency.

But getting the right services can be difficult or impossible — especially for parents who can’t pay attorneys to help them navigate the city’s convoluted system for students with disabilities. Instead, as THE CITY and ProPublica reported last year, kids who are disruptive or aggressive often get pushed out of mainstream schools and into failing special education schools that are packed with other students who have behavioral and mental health challenges. Even if they are capable academically, their chances of graduating with a diploma plummet.

Meanwhile, their odds of encountering police go way up: Special education schools, which disproportionately serve low-income and Black students, call 911 on kids in distress at four times the per-student rate of general education schools, according to a data analysis by Advocates for Children.

In Brooklyn, Paul’s parents are doing everything they can to keep him in a school with general education students. This is his chance to be integrated into mainstream life, his mom said.

On the day after Paul’s school called 911, his parents asked for a meeting with school staff and officials from the Department of Education — something they only knew to do because they were working with paid education advocates, they said. Paul’s dad went to the meeting, which was recorded on Zoom, with a list of questions: What kinds of restraints were used on his son? Could he see a picture of them? Would the school share its plan for responding to students in crisis or its policies on handcuffing kids? What if Paul had another incident — would staff call his parents before calling 911?

School staff said that they had tried to calm Paul down, but no one explained why the NYPD safety agent had become involved or why the school hadn’t called Paul’s parents first. The principal would only say that the school had done nothing wrong. “Protocols were followed,” she said. Everything was “by the book.” Meanwhile, she repeated a list of Paul’s transgressions: He had “assaulted” teachers, his behavior was “egregious.” (Paul’s parents asked us not to use their names or identify his school, in part to protect Paul’s privacy but also for fear of alienating education officials who hold power over Paul’s future school placements.)

After an hour, Paul’s dad was reduced to pleading: “Promise me, if this happens again, you have to call us,” he said. “I'm begging you. This is my son.”

Two weeks after the meeting, the Department of Education transferred Paul to a school that has more experience teaching disabled and nondisabled kids together. It’s a better outcome than many families get, Paul’s mom said. “We’re white, and we have a lot of resources to put toward our son. I have no idea how you would manage this situation without the resources to pay for help.”

So far, things at the new school are going well. Paul’s tantrums have not been quite so explosive, and his teachers seem comfortable managing them, his mom said. “They don’t shame him or drag him through the mud.”

Still, it’s impossible for her not to worry. If Paul was handcuffed at 7, what happens as he gets bigger and older?

She finds herself shutting away the memory of what happened in December. “It’s like this other, alternative reality,” she said. “I’m with my joyful, wonderful child, and I’m like, ‘How could this happen?’”

Sophie Chou contributed data analysis.