This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Source New Mexico. Sign up for ProPublica’s Dispatches and Source New Mexico’s newsletter to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

The wildfire had already burned 160 square miles of northern New Mexico forest last spring when it suddenly surged ahead, reducing to ash the cozy cabin David Martinez had built for himself more than two decades earlier.

Martinez, now 64, had fled days before, one of 15,000 people ordered to leave as the fire spread.

He spent the next three months sleeping near the edge of the fire in his pickup truck, his physical and mental health declining from the smoke, stress and lack of sleep.

Desperate for shelter, he spent $5,000 or so of the emergency aid he’d received from the Federal Emergency Management Agency on a down payment for a late-’90s Vacationaire travel trailer. He placed it on the site of his old cabin in Monte Aplanado, about 35 miles northeast of Santa Fe.

He calls it the “tin can.” Its heater is broken. The cold creeps through its thin walls. Wind rattles the wooden cabinets. But it’s all he could afford.

A year ago, two runaway fires set by the U.S. Forest Service converged to become the Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon wildfire. It rode 74 mph wind gusts, engulfing dozens of homes in a single day as it tore through canyons and over mountains.

The blaze became the biggest wildfire in the continental United States in 2022 and the biggest in New Mexico history. And it was the federal government’s fault: An ill-prepared and understaffed crew didn’t properly account for dry conditions and high winds when it ignited prescribed burns meant to limit the fuel for a potential wildfire.

By the time the blaze was fully contained in August, it had destroyed about 430 homes, according to the Forest Service. Monsoons helped extinguish the fire, but they spurred floods that caused more damage.

FEMA stepped in to help, offering cash for short-term expenses and, after the state requested it, temporary housing to 140 households. But the federal government has acted so slowly and maintained such strict rules that only about a tenth of them have moved in, an investigation by Source New Mexico and ProPublica has found.

A year after the fire began, FEMA says most of the 140 households it deemed eligible for travel trailers or mobile homes — essentially, people whose uninsured primary residences sustained severe damage — have found “another housing resource.”

What the agency doesn’t say: For some, that resource is a vehicle, a tent or a rickety camper. It’s a friend or relative’s couch, sometimes far from home. It’s a mobile home paid for with retirement funds or meager savings.

The fire upended a constellation of largely Hispanic, rural communities that have cultivated their land and culture in the shadows of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains for hundreds of years. Many residents can find their family names on land grants issued by Mexican governors in the 1830s.

Now they’re dispersed across the region, even out of state. Source New Mexico and ProPublica obtained records from local officials and volunteer groups and eventually interviewed more than 50 people who between them lost 45 homes.

Many of them said FEMA’s trailers were offered too late, cost too much to get hooked up or came with too many strings attached. Several said they went through multiple inspections, only to learn weeks later that one rule or another made it impossible to get a trailer on their land. In some cases, FEMA officials told people that their only option was a commercial mobile home park, miles down winding, damaged mountain roads from the homes they were trying to rebuild.

People who between them lost 17 homes said they withdrew from the housing program because of those problems.

As of April 19, just 13 of the 140 eligible households had received FEMA housing. Only two of them are on their own land.

Martinez said he got a call from FEMA in mid-October, seemingly out of the blue. By then, he had been living in the tin can for a couple of months. As temperatures dropped, he had started sleeping on the couch, closer to the space heater.

A FEMA representative asked if he needed a trailer to live in.

“I told them it was too late,” he said. “Way too late.”

FEMA said terrain and weather, among other factors, presented challenges in providing housing to survivors. But the agency said it made an exception to its rules by providing trailers and mobile homes in the first place — normally such programs are reserved for disasters that displace a large number of residents.

The agency said it tries to place temporary housing on people’s property, but couldn’t in many cases because of federal laws and its own requirement that trailers be hooked up to utilities. State and local officials have asked the agency to loosen its rules, but it hasn’t.

FEMA knows it has a problem with its response to wildfires. A 2019 Government Accountability Office report said FEMA’s housing programs are better suited to help those displaced by hurricanes and floods because some victims can remain in their damaged homes, there’s often more rental housing in those areas and there’s more space for large mobile home parks than there is in the rugged mountains scorched by wildfires.

FEMA agreed with the findings and said it would explore providing housing funding to states because they’re better positioned to guide recovery. That didn’t happen after the Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon fire.

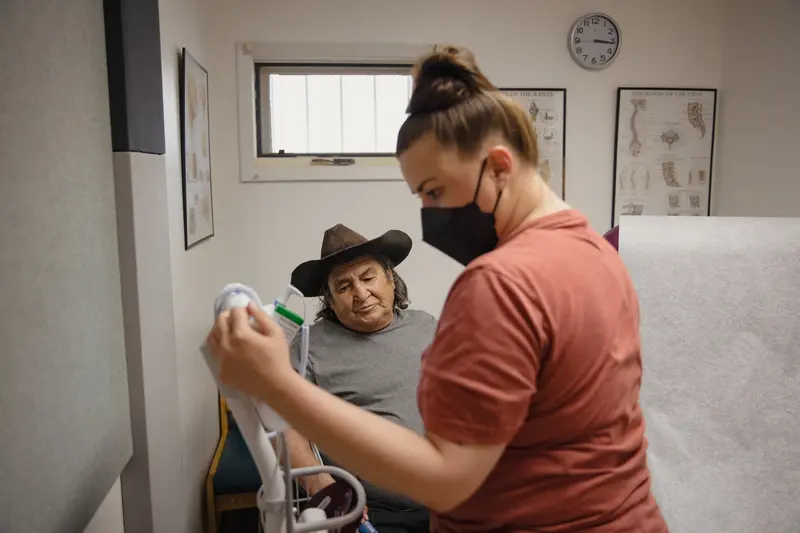

Last month, Martinez woke up on the couch in severe pain from a swollen bladder. Now he needs frequent medical appointments to check his catheter and figure out what’s causing the pain. His sister has been trying to get him a FEMA trailer in a commercial park closer to a clinic in the town of Mora. It’s just 8 miles away, but it can take 45 minutes to drive there.

What neither of them knew when he bought that old trailer last summer is that doing so made him ineligible for a FEMA trailer.

Martinez wants to stay on his property if he can. His great-grandfather once owned the land where he built that cabin. He raised his hands to show his stiff, swollen fingers. “They ain’t worth shit now,” he said. “But a man builds his own castle, right?”

The Cost of Free Housing

By mid-June, firefighters had finally started to get the blaze under control, and people were being allowed back into communities in the area known as the burn scar. New Mexico officials turned their attention to those who had nothing to return to.

Kelly Hamilton, deputy secretary for the state Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, told FEMA in a letter that people were living in their cars, at work and in churches, in campers and even in tents.

He asked FEMA to provide travel trailers or mobile homes. “If the housing situation is not immediately addressed, the survival of each community is bleak,” he wrote.

He cited an analysis showing there was just one rental apartment available in Mora and San Miguel counties, the two hardest hit by the fire. He noted that roughly 20% of residents in those counties were below the poverty line and that one-third of Mora County residents were disabled, according to U.S. Census Bureau figures.

It took FEMA a month to approve Hamilton’s request and about two weeks more to tell the public. On Aug. 2, the agency announced it would launch a small housing program, which “will likely entail placing a manufactured home on the resident’s property for the length of time it takes to rebuild.”

But there were strict rules for where those trailers could go. Recipients would need to have electrical service, septic tanks and drinking water close to the housing site. The agency’s draft contract for the housing program specified details down to the width of straps that were required to secure trailers against wind.

Local and state officials and disaster survivors told Source and ProPublica that the utility requirements were unreasonable, especially in this area. It’s common for homes to be heated with wood stoves fed with timber harvested from the surrounding land. Some people didn’t have running water or septic tanks even before the fire. Electrical outages were common in remote areas.

Martinez’s cabin never had running water; he got it from his neighbor’s well. So even if FEMA had offered him a trailer earlier, he would have had to pay thousands of dollars to build a well — if he could’ve found someone to do it.

“I’m trying to put this diplomatically,” said David Lienemann, spokesperson for New Mexico’s emergency management department. FEMA is “very efficient in deeming people ineligible.”

The effect of those rules is clear. As of April 19, FEMA said 140 households were eligible for trailers, as determined by the agency’s own inspections and policies. Of those, 123 had “voluntarily withdrawn.”

People dropped out because they “opted to live in their damaged homes, located another housing resource or declined all Direct Housing options,” said FEMA spokesperson Angela Byrd in an email. “However, those households remain eligible for the program should their situation change.”

FEMA wouldn’t allow Vicki Garland to connect a trailer to her solar panels, which weren’t touched by the flames. Instead, the agency insisted that she connect to the power grid, which would’ve cost her about $20,000. She’s now moving to the outskirts of Albuquerque, about 140 miles away.

Six individuals and families said they left the program because it would’ve cost too much to hook a trailer up to electricity, restore their wells or meet other utility rules.

Emilio Aragon was living in his office when he was told he was third on the list for a FEMA trailer. After waiting six months, he gave up and spent his retirement savings on a mobile home. He was among six individuals and families who said they were offered housing too late or faced delays that forced them to find housing on their own.

In response to those accounts, FEMA said in a written statement that it must ensure housing is safe and secure. “Generally, this is not a fast process because it requires us to be so thorough and meticulous. Working during the monsoon season meant it took additional time to make sure these sites were safe.”

FEMA has had a hard time getting people into temporary housing quickly after disasters. After Hurricane Ida struck Louisiana in 2021, FEMA said its housing program “is not an immediate solution for a survivor’s interim and longer-term housing needs” because it takes months to get sites ready. The agency praised Louisiana’s decision to launch its own federally funded housing program alongside FEMA’s.

A few months after the storm, The New York Times reported, the state’s program had housed around 1,200 people in about the same time it had taken for FEMA’s program to house 126.

Because FEMA’s housing programs end 18 months after a disaster declaration, every delay runs down the clock. Unless the Hermits Peak housing program is extended, it will expire in November, when the next winter is approaching.

FEMA declined to say whether it would extend the program, saying it would work with the state to meet survivors’ needs.

Wesley Bennett and his wife, JoDean Williams Cooper, said they went through three inspections to see where a trailer could be placed on their property. No spot was suitable, and they were instead offered a site at a mobile home park. Five other individuals and families said they pulled out of the housing program because of the red tape.

FEMA has noted that nine households declined to live in a mobile home park. Several of the trailers it has installed at those sites stand empty.

Some survivors, including Bennett and Cooper, said it wasn’t feasible to live in a trailer park an hour away from the homes they were rebuilding, especially with so many roads washed out by the flooding that followed the fire. They needed to stay on their land to take care of crops and deter theft.

“People who have largely lived in a rural setting are not going to be as comfortable in a trailer park. It’s just their whole way of life,” said Antonia Roybal-Mack, a lawyer who’s from the area and is assisting hundreds of victims in filing administrative claims for damage with the federal government.

“Here’s Hoping It’s a Paperwork Issue”

Erika Larsen and her partner, Tyler White, were living in a camper van after losing their home in the village of San Ignacio when they learned FEMA was offering temporary housing.

Their livelihoods depended on being on their land, they said. Larsen is an herbalist who before the fire made tinctures and elixirs with ambrosia, hops and nettle she grew in gardens dotting the property. White works in construction and gets a lot of her work from neighbors who know where to find her.

Early on, White was feeling optimistic. She posted to a private Facebook group of disaster survivors on Aug. 23, a day after a FEMA inspection.

“Amazingly enough, yesterday we were approved for a trailer to live in. There is only one place to put anything on our property because of flooding. Our well and septic are shot because of fire and floods so we didn’t think we’d qualify. But we did. We should get it in a couple months,” she wrote.

“All this is to say as much as it stinks dealing with FEMA,” she wrote, “as hard of a fight as it can be, you might just get something out of it.”

Two days later, she added something.

Their case manager had “asked us if we wanted to live in a FEMA trailer park. We told him we’d been approved for a trailer at home and he said there was no record of that. Here’s hoping it’s a paperwork issue!”

She and Larsen waited for word while living nearby in their camper van. By late August, afternoon storm clouds often formed over the mountains, bringing monsoons that seeped through the roof and flooded their land. They worried about further damage to their property while they were away.

Two weeks after her first post, White offered another update. FEMA said the proposed site was in a floodplain, so the couple wasn’t allowed to put a trailer there.

“Our case manager said lots of people have been saying they were told they were approved for a trailer just to be declined,” she wrote. “So the moral of my story is: If a bunch of FEMA people come and tell you you are getting a trailer you still might not be eligible.”

They appealed the decision, but more inspections over the next two months determined that other sites on their property were too far from a septic tank, well or electricity hookup.

The agency also apparently made an error in its denial: Inspection records provided by Larsen showed the proposed trailer site isn’t actually in the floodplain on the map that FEMA says it uses for such decisions.

FEMA officials declined to comment on particular cases without written permission from the people who’d filed the claims.

By early November, as temperatures dropped and a long winter loomed, they’d had enough and decided to move into a dilapidated mobile home on a neighbor’s property. The landowner used it for storage, but at least it had a wood stove.

Larsen likened dealing with FEMA to an abusive relationship. “It really has been the worst part of this whole experience for me,” she said. “I feel capable of doing the work of processing this trauma. But having to keep talking to these people that are just fucking with my mind is pretty intense.”

The Flood That Never Came

It wasn’t just residents who saw that the program wasn’t working. State and local officials asked FEMA to relax its requirements or make accommodations, but the agency didn’t budge.

After FEMA announced in early August that it would provide trailers, officials met with Amanda Salas, the planning and zoning director for San Miguel County, and told her inspections and approvals could take 10 weeks.

Across the burn scar, survivors were arranging inspections with caravans of contractors and FEMA employees who poked around their properties to evaluate possible sites.

In late-September, Salas cleared her desk, expecting a flood of building permit requests from residents seeking permission to place FEMA trailers on their land.

Getting people back was “number one,” she said in an interview. “I need them to be in a warm place, you know?”

The flood of permit requests never came. About 35 people expressed interest in FEMA’s housing program when she told them about it after they showed up in her office to ask questions about cleanup and rebuilding. Most withdrew due to bureaucratic hurdles and delays, she said. Her counterpart in Mora County said he observed the same thing.

FEMA spokesperson Aissha Flores Cruz said in an email that the agency respects survivors’ decisions not to apply.

In mid-October, Salas attended a meeting of local and federal officials. It was her first opportunity to talk to high-ranking FEMA officials in person, and she spoke up.

She told them it didn’t make sense to require electricity, wells or septic systems in a rugged area where people didn’t rely on those services before the fire. She asked FEMA to provide gas generators.

“It seemed like they heard us,” Salas said of the meeting. “But they didn’t do anything about it.”

Meanwhile, state officials sought waivers for the utility requirements and urged FEMA to outfit homes with portable water tanks or composting toilets. The state wanted “to at least get people back in a safe, warm home, on their property,” said Lienemann, the state emergency department spokesperson.

On Dec. 19, as temperatures dropped to single digits in parts of the burn scar, the state had not heard back from FEMA about its request. Ali Rye, an official with the state Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Management, asked for a response and again requested that FEMA approve waivers for high-need cases.

Lienemann said FEMA told the state that it would make decisions on waiving rules on a case-by-case basis. The agency never made any exceptions.

FEMA said federal law doesn’t allow it to waive the rules for its housing programs. And Flores Cruz said FEMA funds cannot pay to reconnect or rebuild utilities because that would be “permanent work” funded through a program intended to be temporary.

Payment for permanent repairs falls to a special FEMA claims office created in January, but it hasn’t cut any checks to survivors yet. Congress set aside about $4 billion in compensation funds in acknowledgement of the federal government’s role in starting the fire.

Sheltered but Not Home

Daniel Encinias is one of the two people who got trailers on their own land. Each month, a FEMA representative stops by and asks for proof that he’s trying to find permanent housing — one of the conditions of living in the agency’s trailers.

He tells them he’s waiting for a check from the $4 billion compensation fund. “The minute FEMA releases the money and gives me enough money to build my home back,” he said, “that’s when things are gonna get done.”

The claims office will handle such requests. It was supposed to start sending out money in early 2023, but the agency is behind schedule.

“I have to tell you, opening an office is hard,” claims office Director Angela Gladwell told a packed lecture hall of frustrated fire survivors at Mora High School on April 19.

FEMA said it now expects to open three field offices to the public this month and it is trying to make partial payments while it finalizes its rules. Case navigators — who are locals who know the communities, the agency pointed out — are reaching out to those who have filed claims for damages.

The throngs of FEMA employees who swarmed into the area last summer to offer short-term aid have moved on. Some survivors are in limbo, running low on disaster aid and lacking the money to rebuild.

For Rex “Buzzard” Haver, a disabled veteran, the first disaster has split into a tangle of smaller ones. After his home burned in May, his family spent nearly $64,000 on a mobile home — more than the roughly $48,000 he’s gotten from FEMA so far. He doesn’t have the money to install a wheelchair ramp.

The company that delivered his replacement home broke its windows, tore the siding and ripped off lights during delivery. But they won’t come and fix it until the county repairs the road to his house. Haver has no washer or dryer, and for months, his satellite TV provider kept calling to collect a dish that had melted into black goo.

Haver didn’t learn that FEMA was offering trailers until several months after his new mobile home arrived in July, according to his daughter, Brandy Brogan. Now he’s in hospice, and he’s struggling.

“He doesn’t feel that he has a purpose anymore,” Brogan said. “There’s nothing for him to do. There’s nowhere for him to go.”

On a recent snowy afternoon, just down the road from Haver, strong winds rushed past blackened trees and through gaps in David Martinez’s trailer. He raised his voice to be heard over the wind.

“I’ve never been a sick man,” he said, wincing. “Till lately.”

Martinez can hardly walk due to his medical problems. The once-avid outdoorsman spends most days sitting in the kitchenette, the space heater on full blast, watching hunting shows on a 16-inch television. He ultimately got $34,000 from FEMA in short-term aid, but he’s down to a few grand.

On a recent afternoon, his sister, Bercy Martinez, and her grand-nephew drove up the washed-out driveway to deliver groceries and bottled water, which she does a few times a week. She loaded her brother’s fridge. “This is very good,” she said in Spanish of the meatloaf she bought. “It’s not too spicy.”

She’d been asking FEMA for weeks about getting her brother a spot in a mobile home park so he doesn’t have to navigate the bumpy road that makes drives to the clinic so painful.

Two weeks ago, she reached a FEMA employee on the phone and asked if the housing program that had arrived too late for her brother could help him now. The answer, she said, was no. He’s no longer eligible because he has a place to live.

April 26, 2023: This story originally referred incorrectly to a deputy secretary in New Mexico’s Department of Homeland Security and Emergency Management. Kelly Hamilton uses male pronouns, not female pronouns.

Byard Duncan contributed reporting.