This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Searchlight New Mexico. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

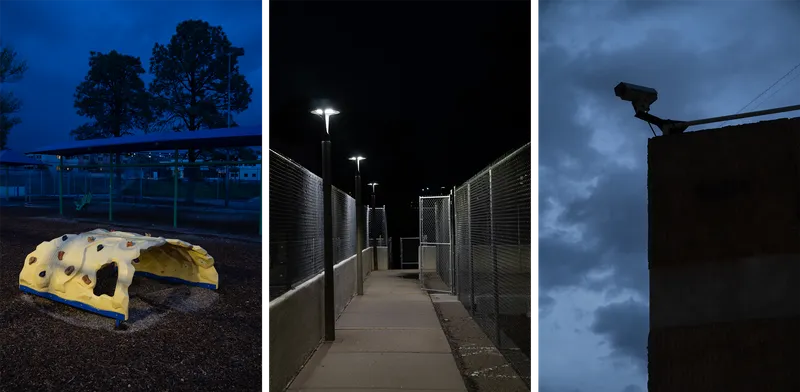

Four years ago, kids in New Mexico’s child welfare system were in a dire situation. Kids were being cycled through all sorts of emergency placements: offices, youth homeless shelters, residential treatment centers rife with abuse. Some never found anything stable and ended up on the streets after they turned 18.

A lawsuit brought by 14 foster children in 2018 claimed the state was “locking New Mexico’s foster children into a vicious cycle of declining physical, mental and behavioral health.” The state settled the case in February 2020 and committed to reforms.

But two and a half years later, New Mexico has delivered on just a portion of those promises, leaving some of the state’s most vulnerable foster youth without the mental health services they need.

In a settlement agreement for the suit, known as Kevin S. after the name of the lead plaintiff, the state committed to eliminating inappropriate placements and putting every child into a licensed foster home. It also agreed to build a new system of community-based mental health services that would be available to every child in New Mexico, not just those in foster care.

Yet the Children, Youth and Families Department continues to make hundreds of placements in emergency facilities every year. Although CYFD has reduced the number of children in residential treatment centers, it continues to place high-needs children and teens in youth homeless shelters. Mental health services for foster youth, which includes all kids in CYFD protective services custody, not just those in foster homes, are severely lacking, lawyers and child advocates say.

The department said it has worked to build new mental health programs and services for kids. “Most of these efforts are successful and are on a path to expansion,” Rob Johnson, public information officer for CYFD, said in a written statement.

“This is an incredible amount of progress made in a relatively short time in a system that had been systemically torn down and neglected,” he wrote. “We’re not where we want to be, and we continue to look and move ahead to create and strengthen the state supports for those with behavioral health needs.”

A Push to Get Kids Out of Residential Treatment Centers

The Kevin S. lawsuit was filed amid a national reckoning over child welfare agencies’ reliance on residential treatment centers. Similar lawsuits in Oregon, Texas and elsewhere accused states of inappropriately placing kids in residential treatment centers, often far from their homes, and in other types of so-called congregate care. Kids placed in those facilities got worse, not better, the suits argued.

After Texas failed to comply with court-ordered fixes to its child welfare system, a federal judge said she plans to fine the state. The Oregon lawsuit is proceeding despite the state’s efforts to have a judge dismiss the case.

Several months before the New Mexico suit was filed, federal lawmakers passed the Family First Prevention Services Act, which redirected federal funding in order to pressure states into phasing out large residential treatment centers. In their place, the law called for a new type of facility to treat children with acute mental health needs: small, strictly regulated facilities called qualified residential treatment programs.

Child welfare advocates across the country welcomed these reforms. But they warned that shutting down residential treatment centers without alternatives could leave kids in an equally desperate situation — a scenario they said was reminiscent of the effort to shut down mental hospitals starting in the 1950s.

“I believe we do need a change in group care,” U.S. Rep. Lloyd Doggett, D-Texas, said during a 2016 debate in Congress. “One has to ask where these children will go if those group facilities are no longer available.”

“We Know We Can Find Them Better Beds”

The first residential treatment center in New Mexico to close, in early 2019, was the state’s largest: a 120-bed facility in Albuquerque called Desert Hills that was the target of lawsuits and an investigation into physical and sexual abuse.

Many of the lawsuits’ claims — which Desert Hills and its parent company Acadia Healthcare denied or claimed insufficient knowledge of — remain unresolved pending trials. Other cases have been settled, with undisclosed terms.

A spokesman for Acadia said Desert Hills decided not to renew its license “given the severe challenges in the New Mexico system” and worked with CYFD on a transition plan.

“Of course we are not going to drop kids on the street,” CYFD’s chief counsel at the time, Kate Girard, told the Santa Fe New Mexican soon after. “We know we can find them better beds.”

Some of the kids who had been living at Desert Hills were sent to homeless shelters. Others went to residential treatment centers in other states, which the CYFD secretary at the time publicly admitted put kids out of sight and at higher risk of abuse.

State officials have said they send kids out of state when they don’t have appropriate facilities in New Mexico, and they make placements based on individualized plans for each child.

Those out-of-state residential treatment centers included facilities run by Acadia. One foster teen was raped by a staffer at her out-of-state placement, according to an ongoing federal lawsuit. The facility has denied the allegation in court; Acadia has denied knowledge of the alleged assault.

In January 2019, a few months after the Kevin S. lawsuit was filed, New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham took office after promising during her campaign to address the state’s dismal national standing in child welfare. She asked for an increase in CYFD’s annual budget, and the legislature complied, appropriating an 11% increase over the year before.

“A top CYFD priority is increasing access to community-based mental health services for children and youth,” Lujan Grisham said in a speech in June 2019. “We are expanding and will continue to expand these programs aggressively and relentlessly.”

State officials settled the Kevin S. suit in February 2020, agreeing to a road map for reforming its foster care system. Among them: a deadline later that year to stop housing kids in CYFD offices when workers couldn’t find a foster home.

That deadline passed, but CYFD didn’t stop. The practice continues today.

While the state is committed to do everything it can to keep children from sleeping in offices, sometimes — such as in the middle of the night — the best option is to let children stay in an office while staff search for an appropriate placement, CYFD spokesperson Charlie Moore-Pabst wrote in an email.

All of CYFD's county offices have places for children to sleep, he explained. “These rooms are furnished like a youth’s bedroom, with beds, linens, entertainment, clothing, and access to bathrooms with showers,” he wrote. "They’re not merely office spaces."

The state continued to crack down on residential treatment centers. In 2021, a facility for youth with sexual behavior problems closed after the state opened an investigation into abuse allegations. Some of those residents were moved to homeless shelters.

“From our point of view, it was almost clear that the state didn’t want us to be there,” said Nathan Crane, an attorney for Youth Health Associates, the company that ran the facility. Crane said that to his knowledge, none of the allegations against the treatment center were substantiated. “We mutually agreed to shut the door and walk away.”

Johnson said that when it learned of safety concerns at these facilities, it promptly investigated. “Following the investigations,” Johnson wrote, “CYFD determined that it was in the best interest of the children in its care to assist in the closure of the facilities and find alternate arrangements for each child.”

Meanwhile, the state lagged in meeting its commitments to build a better mental health system. The state had met only 11 of its 49 targets in the Kevin S. settlement as of mid-2021, according to experts appointed to monitor its progress.

Although the parties to the suit agreed to extend deadlines during the pandemic, the plaintiffs said in a November 2021 press release, “This dismal pace of change is not acceptable. The State’s delayed and incomplete responses demonstrate that children in the State’s custody are still not receiving the care they need to heal and grow.”

“Sick to My Stomach After They Put All Those Kids on the Street”

In December 2021, an Albuquerque residential treatment center called Bernalillo Academy closed amid an investigation into abuse allegations. The largest remaining facility at the time, Bernalillo specialized in treating kids with autism and other developmental disabilities.

“Being accused of abuse and neglect is a serious offense that questions our integrity and goes against what we are working hard for here at Bernalillo,” Amir Rafiei, then Bernalillo Academy’s executive director, wrote in an email to CYFD challenging the investigation.

Child welfare officials called an emergency meeting of shelter directors, looking for beds for the displaced kids. CYFD went on to place some of those kids in shelters.

”It’s important to note that placements were only made to shelters that fit their admission criteria,” Johnson wrote in the statement to Searchlight and ProPublica.

Michael Bronson, a former CYFD licensing official, said state officials had no plan for where to put the kids housed in those residential treatment centers.

“I thought it was almost criminal,” said Bronson, who conducted the investigations into Desert Hills and Bernalillo. “I was sick to my stomach after they put all those kids on the street.”

CYFD Secretary Barbara Vigil insisted in an interview that officials did have a plan. Teams of employees involved in the children’s care discussed each case in detail, she said: “Each of those children had a transition plan out of the facility into a safe and relatively stable placement.”

But Emily Martin, CYFD Protective Services Bureau Chief, acknowledged, “When facilities have closed, it has left a gap.”

There are now 130 beds in residential treatment centers in the state, less than half the number before the Kevin S. suit was filed.

State Says It’s Working on New Programs

Frustrated with the lack of progress, the Kevin S. plaintiffs’ attorneys started a formal dispute resolution process in June. The state agreed to take specific steps to comply with the settlement agreement.

The monitors have written another report on the state’s compliance with the settlement, which is due to become public later this year. Sara Crecca, one of the children’s attorneys involved in the settlement, said her team has been involved in discussions with the monitors about the report, but she’s not allowed to disclose them.

“What I can say is that my clients have seen no substantial change,” she said. “If the state was following the road map in the settlement, that wouldn’t be the case.”

Officials stressed that they are making progress. They say they have opened more sites that can work with families to create plans of care; expanded programs for teen parents and teenagers aging out of care; and made community health clinics available to foster children.

CYFD also has funded community health workers and created a program to train families as treatment foster care providers. Four families are participating in that program, Johnson, the CYFD spokesperson, wrote. The department plans to open two small group homes, with six beds each, for youth with high needs, including aggression.

Four years after the federal Family First Act was passed, New Mexico has not licensed a single qualified residential treatment program, the type of facility that is supposed to replace residential treatment centers. The state said in an email to Searchlight and ProPublica that it is “laying the foundation” to create those facilities.

In the meantime, because of the law, the state is on the hook to pay for any stays in congregate care settings that last longer than two weeks.

In August, Vigil appeared before New Mexico legislators to update them on the department’s progress in building a new system of mental health services. In response to pointed questions, she said the department is required by law to serve the highest-needs kids, but it wasn’t doing so. “Quite frankly,” she said, “we don't have a system of care in place to do that.”

Another deadline looms. By December, the state must have all of those new programs available to the children in its care.

“Will it be 100%?” Vigil said in an interview. “Again, I would say no, but that doesn't mean that the system of care is not improving tremendously under this administration.”

Mollie Simon contributed research.