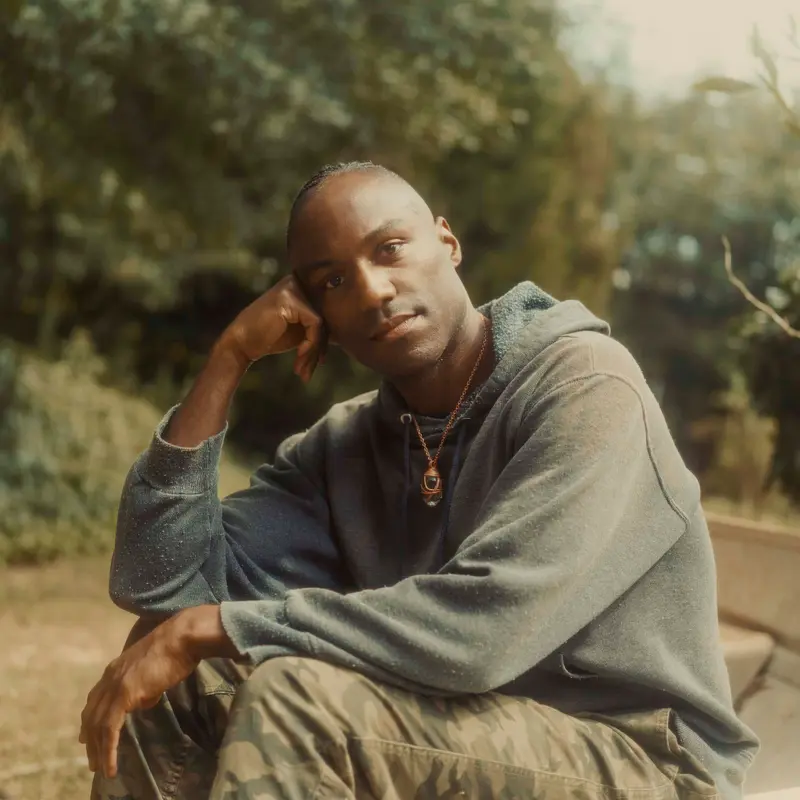

On a Monday morning in mid-July, William L. Jeffries IV decided it was time to call a colleague for help. Jeffries is a senior health scientist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, where he researches the ways that racism and homophobia impact health in the United States. Jeffries, who describes himself as a same-gender-loving Black man, sees the work as a way to serve his people and, by extension, God.

This call, however, was a personal one. He was sitting on his bed in pain, and he was angry.

Jeffries was angry for the hundreds of people, mainly gay and bisexual men, who were infected with monkeypox. He was angry that the burden was falling particularly hard on Black and Latino communities. He was angry that the federal government had been saying for eight weeks that it had the tools necessary to deal with the growing outbreak yet people were still struggling to find care.

And he was angry because he himself now had monkeypox and couldn’t find anyone to diagnose or treat him.

Jeffries told his colleague, who was helping to lead the CDC’s monkeypox response, about his ordeal. He knew then that he was a victim of the very failures of the American public health system that he studies.

“I myself am a trained disease detective. I have led outbreak investigations for HIV and syphilis. I am a published scientist. And I know a lot about public health and infectious disease transmission,” Jeffries said. “I emphasize my training and my experience because if I had to go to three different places before I got diagnosed, imagine what the average gay man has to do?”

By the end of September, more than three-quarters of people diagnosed with monkeypox in Georgia were Black, and Georgia had the second-highest rate of cases among all U.S. states, trailing New York. As the outbreak has spread, the federal government has been forced to reckon with the disease’s disproportionate burden on Black communities around the country. Black people make up more than half of monkeypox cases nationally, even as they represent less than 14% of the U.S. population. More than 26,000 people have been infected nationwide.

CDC Director Rochelle Walensky recently acknowledged that she and other top public health officials anticipated these inequities; decades of tracking HIV and other infectious diseases made them predictable. Public health officials, who lost the trust of many Americans in the first two years of the COVID-19 pandemic, had a chance to show that they had learned from their mistakes when monkeypox hit. Yet what happened to Jeffries and others in Georgia in the early months of the outbreak shows how federal officials, who suspected that communities of color would get monkeypox at higher rates, failed to intervene in ways that could have prevented — or at least lessened — that suffering.

“A lot of people got hurt,” said Dr. David Holland, the chief clinical officer for the Board of Health in Fulton County, which covers 90% of Atlanta. He too is angry about the first months of the federal response. “You can debate what the right thing to do would have been, but doing nothing is not on that list. And that’s kind of what was done.”

A dozen infectious disease experts told ProPublica that the likely trajectory of the virus in the U.S. was obvious once reports surfaced in May saying that monkeypox had found its way into communities of gay and bisexual men in Europe. They knew then that while it would most likely spread first among wealthier, whiter communities, Black and Latino men would soon bear the brunt of the disease. They knew this because it is the path that many infectious diseases have traveled before.

The reasons why are not a mystery either. Among other things, Black people are less likely than white people to have a regular doctor, less likely to have insurance coverage and more likely to have HIV, diabetes and other diseases that generally put people at greater risk for new infections. White people are more likely to have benefits that can lessen the effects of illness, such as jobs that allow them to take paid sick leave and wealth that can buy them better care.

Federal and state officials nevertheless failed to make testing readily available, slow-walked the rollout of vaccines and didn’t make it clear during the first two months of the outbreak that people of color, like Jeffries, were at elevated risk for harm. Those missteps amplified long-standing health inequities.

“Any time you fumble the response to an epidemic it will cut through the weakest seams in your society,” said Dr. Jay Varma, a professor at Weill Cornell Medical College and former CDC official.

When Jeffries was 9 or 10 years old, his father shared with him a book from 1928 called “Leaders of the Colored Race in Alabama.” Inside was a photo of his great-grandfather and namesake, Dr. William L. Jeffries. Jeffries was blown away that in the early 20th century, a Black man could achieve the level of education — a doctorate in divinity — required to earn him the title of doctor. He said as much to his father, who responded that Jeffries could be a doctor, too. From that moment on, he knew he would follow in his great-grandfather’s footsteps. “I had to be Dr. Somebody,” Jeffries said. “That was just part of my destiny.”

He was interested in the health of communities, and so in 2004 he moved away from his home in Polk County, Florida, for the first time and entered a doctoral program in sociology at the University of Florida. In his first year, he remembers a professor explaining how the CDC responds to infectious disease outbreaks. The professor described disease investigators as the “cream of the crop.” For Jeffries, this was an epiphany: “Immediately, I just knew that was what I was supposed to be.”

Four years later, with a Ph.D. in hand and a Dr. in front of his name, Jeffries entered the CDC’s Epidemic Intelligence Service. There, he trained to be a disease investigator like the ones his professor had told him about. It was the only job he applied for. Jeffries has been with the CDC ever since.

Now 42, Jeffries is a senior health scientist in the Office of Health Equity in the Division of HIV Prevention. He investigates the factors that place vulnerable populations at risk for HIV and other diseases. On average, gay and bisexual Black men have fewer sexual partners than their white counterparts and are more likely to use condoms, and yet Black men have six times the rate of HIV. White people get earlier and better access to new treatments and prevention. Many Southern states have not expanded Medicaid to offer insurance coverage for all impoverished adults, leaving people there less likely to have a doctor and worse off when they do get sick.

“God has had me be here to fight for the oppressed and to be a voice for those who, in many instances in our society, do not have a voice that can be heard by people in positions of power,” Jeffries said. “And my voice is what I use to serve those who Jesus called the least of these among us.”

Jeffries understands that he is in important ways one and the same with the people he researches, and he knows what that means for his vulnerability to disease. So when reports of monkeypox began surfacing, he kept an eye on it. He understood himself to be at risk and wanted to get vaccinated because he knew that, unlike with HIV, condoms do not prevent transmission of monkeypox. He also knew the vaccine wasn’t available in Atlanta yet. At the same time, the risk seemed distant. Government officials said there were only a couple dozen cases in metro Atlanta — a city of over 6 million people — and they made it sound like they had the situation under control.

Jeffries knows when he got monkeypox. It was during a sexual encounter in the early hours of Saturday, July 9. Later that same day, Fulton County Board of Health staff finally held its first monkeypox vaccine clinic.

By Sunday night, Jeffries felt some itching and irritation. A couple days after that, he had a fever, chills and sores around his anus. So on Friday, he went to an LGBTQ-friendly health clinic, told staff that he thought he might have monkeypox and asked for a test and vaccine. They had neither.

Instead, he said they tested him for a range of sexually transmitted diseases and treated him for a suspected case of chlamydia, though results later showed he didn’t have any of those diseases. Jeffries was surprised that in Atlanta, where there were already more than two dozen known monkeypox cases, the clinic couldn’t test him for it. More than eight weeks had passed since the first case was diagnosed in the U.S., and testing was supposed to be widely available.

Frustrated, he went home and isolated from other people. The pain kept growing worse, so late on a Saturday night he sought comfort in an epsom-salt bath and lingered in the warm water until just after midnight. As he was getting out, he noticed a lesion on his chest, close to his left shoulder. Confused, he reached for an itch on his back and felt another bump. He looked down and there was another lower on his torso. They were spreading so fast.

The next morning, Jeffries lay in his bed, uncomfortable and exhausted, and prayed. He knew it was time to go to the emergency room.

He thought his best bet would be a hospital attached to a university, as they tend to have more up-to-date knowledge and connections to public health departments. And he knew just the place: Emory University’s renowned teaching hospital on Clifton Road, a stone’s throw from CDC headquarters. “Atlanta is this hub for Black, gay and bisexual men, and the CDC is right here. Surely, these factors would converge to lead you to have vaccine and treatment available,” Jeffries recalled thinking.

But at Emory it was more of the same. The ER doctor, Jeffries said, knew nothing about monkeypox. Jeffries said he brought a list of the two vaccines and four possible treatments, pulled from the CDC website, but the doctor didn’t know about any of them and, regardless, said they were not available at Emory.

The ER doctor, Jeffries said, swabbed one of his lesions to test it for the monkeypox virus. Jeffries couldn’t understand why the hospital didn’t send in an infectious disease specialist. The hospital, he said, sent him home with prescriptions for ibuprofen and a steroid foam.

And so, the following morning, in severe pain, he called a trusted CDC colleague, Dr. John Brooks. Brooks usually serves as the chief medical officer for HIV prevention but is currently helping to lead the nation’s monkeypox response. Jeffries was desperate to find treatment and thought Brooks could help. He also wanted Brooks to know just how bad the situation was. “I knew that gay and bisexual men in Fulton County, irrespective of their race, were going to be placed at harm because of the overall ignorance, the blundering and the lack of resources,” Jeffries said.

When Jeffries made that call, the U.S. was nearly nine weeks into the monkeypox outbreak. Officials from the White House and the Department of Health and Human Services assured the public that they were responding in full force and had all the necessary tools — a test, a treatment and a vaccine. But they showed little urgency to use them.

Take the vaccine. Concerned that terrorists may use smallpox as a weapon to attack the U.S., federal officials invested nearly $2 billion in the development and manufacturing of the Jynneos vaccine to safeguard against that threat. In 2019, the Food and Drug Administration approved that vaccine for use against both smallpox and monkeypox, which are in the same family of viruses, and health officials keep doses in the Strategic National Stockpile.

But they had a very limited supply when cases first appeared in the U.S. in mid-May. In the preceding years, as hundreds of thousands of doses expired, they waited to order more, holding out for a different preparation of the vaccine with a longer shelf life, as The New York Times previously reported. The 372,000 doses that were ready in vials were mostly in Denmark.

In late May, officials at the Biomedical Advanced Research and Development Authority, the arm of the federal government that develops and procures drugs and vaccines to safeguard against pandemics and other hazards, placed orders for 72,000 doses. “We are prepared with both the vaccines and antivirals needed to protect the American people,” Dawn O’Connell, the HHS assistant secretary for preparedness and response, wrote in a blog post on May 24.

Three weeks later, O’Connell wrote that those 72,000 vaccine doses were in the federal government’s “immediate inventory.” Two more weeks passed, and HHS announced it would make 56,000 doses “available immediately.”

By then, it was the end of June, and Atlanta hadn’t held a single vaccine drive.

That wasn’t for lack of trying. With cases climbing in June and Georgians waiting for their first allotment of vaccines, Holland, the chief clinical officer for Fulton County’s Board of Health, made an official request for ACAM2000, an older vaccine made to ward off smallpox. It’s been available by the millions since 2008, when it was added to the Strategic National Stockpile, before the newer Jynneos vaccine existed. But the older vaccine can cause side effects, making it unsafe to use for many people, including those who are pregnant, have HIV, have weakened immune systems or have various skin conditions.

Federal officials said states could order ACAM2000, but they didn’t exactly endorse it. Holland said Georgia officials turned down his request. He understands the concerns and respects the decision not to use ACAM2000. But he’s frustrated that in the first months, it felt like the answer to every effort at prevention was just “no.”

In a written statement, Nancy Nydam, a spokesperson for the Georgia Department of Public Health, referenced the many potential side effects of ACAM2000 and noted that no other jurisdiction has used that vaccine during the monkeypox outbreak.

When Fulton County finally received its long-awaited shipment of vaccines in July, it included enough for just 200 people. More dribbled in over the weeks that followed.

By comparison, Canadian officials began vaccinating at-risk people in early June. In Montreal alone, officials vaccinated more than 15,300 people through the end of July, according to data provided to ProPublica by the city’s health department. A friend of Jeffries’ was able to get vaccinated at an outdoor walk-up clinic in Montreal’s Gay Village neighborhood on Aug. 1 while he was in the city for the International AIDS Conference. The health workers didn’t care that he wasn’t Canadian.

“We know we live in a global village. We thought making no barriers was the most effective strategy,” said Dr. Genevieve Bergeron of the Montreal public health department.

Georgia currently has more than two and a half times the number of monkeypox cases per capita as Quebec, the province where Montreal is located.

“The thing that is most galling to me is that this was predictable,” said Greg Millett, a former CDC researcher and current vice president and director of public policy at amfAR, a nonprofit dedicated to AIDS research and advocacy. Around the time Jeffries was infected and Atlanta held its first vaccine clinic, there were about 700 known cases in the U.S., nearly all among gay and bisexual men, and the cases were growing exponentially. And yet, Millett said, the U.S. was dragging its feet. To Millett, it’s hard not to see homophobia and racism as an underlying reason. “If this was another population, would they have moved this slowly?”

Within an hour of calling his colleague on July 18, Jeffries got a same-day appointment with Dr. Kimberly Workowski, an infectious diseases specialist at Emory University. She also helps write the treatment guidelines for sexually transmitted diseases at the CDC. In an Emory exam room, Workowski donned protective equipment — goggles, gloves, masks and gowns — to examine Jeffries.

The lesions definitely looked like monkeypox, Workowski told him. She gave him an hourlong work-up, checking his body and talking through his symptoms. He’d had bad experiences with the medical system before, like the time he went in for routine testing and a doctor told him he shouldn’t have sex with other men because that’s how you get sexually transmitted diseases. So he didn’t take it for granted that she was treating him with dignity.

Jeffries said she told him that in the ER, they only swabbed one lesion when they were supposed to swab two or three and that regardless, the sample could not be located. Jeffries was aghast. Workowski counted his lesions and swabbed several of them for a new test, which would ultimately come back as positive.

A spokesperson for Emory Healthcare did not answer questions about Jeffries’ care. (Jeffries signed a privacy waiver to allow Emory to discuss the care he received in the emergency room on July 17.) In a written statement, the spokesperson said Emory Healthcare remains “steadfast in providing excellent and equitable health care to all of our patients.” Emory’s emergency departments follow a standard protocol for suspected monkeypox infections that “includes triage, testing and if necessary, referral to a specialist,” she wrote. “If needed, patients will be admitted to the hospital.”

The day after Jeffries saw Workowski, her office called to tell him that an experimental antiviral drug known as TPOXX was ready for him to pick up.

Once he started on the medicine, the lesions quickly stopped growing and spreading. But the sores and inflammation in the lining of his rectum were causing the worst pain he’s ever experienced, so bad that he couldn’t sleep. Five days after his first trip to the emergency room, he drove himself to a different Emory ER, this one in Midtown, which quickly admitted him. He spent the next four days in the hospital on a cocktail of medications that finally dulled his pain.

He was in isolation but felt less alone than he had in days. The doctor leading his care put her hand on him while they talked and asked how he was doing. Staff chatted with him about his life outside of monkeypox. He knew the hospital was busy, but no one ever seemed rushed. “They took the time to talk to me and make me feel OK,” he said.

At that point, physicians wishing to give TPOXX to patients had to fill out over 100 pages of paperwork. The medication was initially developed by the federal government, and the U.S. holds more than 1.7 million doses in its stockpile. The treatment has been approved for monkeypox in Europe, but it is available only as an experimental drug in the U.S. In August, the CDC slimmed down its paperwork, but even today, it can take more than an hour to fill it out and TPOXX has been hard to get.

Through the end of June, HHS officials had sent out enough medicine to treat 300 people nationally. From around the time of Jeffries’ hospitalization in late July through the end of August, physicians in Georgia handed out just over 600 courses of the treatment, according to data provided to ProPublica by the Georgia Department of Public Health. That would have been enough to cover just half of the people diagnosed during that time.

The Georgia Department of Public Health did not provide data on the race and ethnicity of TPOXX recipients. But nationally, as of Sept. 28, white people make up 28% of cases and have received 34% of the courses of treatment, according to preliminary data released by the CDC. The share that went to white people during the early months of the outbreak was even higher, according to CDC research.

Jeffries feels certain he could have avoided the worst of his pain and his time in the hospital if he had received treatment sooner.

When Jeffries got out of the hospital, he called friends and colleagues. Georgia — especially its Black and queer communities — needed more resources. He wanted people to know how bad it was and that things shouldn’t be this way.

He phoned Justin Smith, his friend who was able to get vaccinated at the AIDS conference in Montreal. The director of the Campaign to End AIDS at a group of HIV clinics in the Atlanta area, Smith had helped organize a virtual town hall with other activists.

There, Joshua O’Neal, the sexual health program director for the Fulton County Board of Health, told attendees that it was OK to be angry about the government’s response so far, that he sure was. O’Neal shared alarming statistics: Cases of monkeypox in Fulton County had nearly doubled in the three days before the event, and more than half of the people there with monkeypox also had HIV. Of the people with both viruses, 80% were Black. “It is our responsibility to ensure that those folks are the ones we’re reaching out to,” he told the group.

O’Neal acknowledged that the scant appointments for the first two vaccine clinics were gone within minutes and that most who got them were white. Going forward, he vowed to partner with community organizations to get them out more equitably.

On Aug. 4, 10 days after Jeffries got out of the hospital, the Biden administration declared a public health emergency. When that happened, as Margo Snipe reported for Capital B, a nonprofit news site for Black communities, officials made no mention of the growing racial and ethnic disparities.

Jeffries was encouraged, though, that the White House appointed Dr. Demetre Daskalakis, the head of the CDC HIV division where Jeffries works, to a top position on its monkeypox response team. Jeffries knows him and says he strongly believes that Daskalakis is committed to getting the disparities in check. The White House declined to make Daskalakis available for an interview and suggested ProPublica contact the CDC instead.

The CDC declined to make Walensky, its director, available for an interview. Walensky’s deputy press secretary referred a reporter to Walensky’s comments at a White House briefing on Sept. 15. “It is critical that education, vaccinations, testing and treatment are equally accessible to all populations, but especially those most affected” by the monkeypox outbreak, Walensky said. “CDC remains committed to collaborating with jurisdictions to reduce health disparities.”

A different CDC spokesperson, Kevin Griffis, followed up and said that the agency appointed an equity officer to its response team in May and did outreach to LGBTQ groups in the weeks that followed. On its website in early June, the CDC first published guidance for ways to avoid getting monkeypox and has been updating it ever since. “This was an issue that Dr. Walensky and Dr. Daskalakis both talked about really as part of essentially every discussion that would be had about the outbreak: ensuring that we were doing everything we can to reach diverse populations,” Griffis said.

By early September, the spread of new cases began slowing in much of the U.S. Experts largely credit that decline to behavior change among queer men. In an August survey, gay and bisexual men reported changing their sexual practices to protect themselves. It’s too soon to say whether vaccine drives, which were ramped up at the end of August, are playing a role, experts say. In an effort to understand potential treatments, federal officials began recruiting monkeypox patients for a clinical trial of TPOXX. And O’Connell, of HHS, told a Senate committee on Sept. 14 that she had made more than 1.1 million vials of Jynneos vaccine available to health departments.

The Fulton County Board of Health made good on its promise and partnered with various community organizations to get the word out to the Black community. As of Sept. 15, more than half of the first doses of the vaccine have gone to Black people, according to a county report. Nydam, the Georgia Department of Public Health spokesperson, wrote that the state worked with federal officials to give out more than 4,000 doses at Atlanta’s Black Pride festival on Labor Day weekend.

“High demand and limited vaccine supply created access challenges for vaccines in general during the early weeks of the response, but the partnerships with community-based organizations greatly helped us with addressing health disparities in our vaccine roll out,” Nydam wrote.

Still, Congress has not designated any money for the monkeypox response. The vaccine and TPOXX are provided for free, but Fulton County has had to use its STD budget to run its vaccine clinics. “We’re spending our entire STD budget for the year and hoping that at some point the federal government will reimburse us,” Holland said. That’s money that also needs to be used for the simultaneous epidemics of HIV and syphilis, both of which disproportionately harm Black men and women.

While the spread of monkeypox is slowing, Black Americans represent a growing share of the overall cases — from 37% on Aug. 28 to 51% of all cases just three weeks later, according to the most recent data available.

Jeffries is still dealing with complications from monkeypox. But his bigger concern, one he shares with many in the HIV prevention community, is that Black LGBTQ people will be left dealing with monkeypox infections even if it largely disappears from the rest of the population. That’s another pattern they have seen many times before.

Thinking about what should have been done differently in those early months, it’s clear to Jeffries that everything the federal government has done since August should have happened much sooner. That could have prevented a lot of harm.

But his work also tells him that stopping these predictable patterns altogether will require dealing with the racism, homophobia and economic inequality at the root of so many health disparities. Lately he’s been thinking about a lesson his grandfather taught him when he was young.

Jeffries’ grandfather worked 12 hours a day, six days a week in Florida’s citrus groves, and he was still poor. He kept a garden to feed the family, and he sometimes took Jeffries with him to teach him how to farm. One day Jeffries was pulling at the weeds, snapping them off at the top. His grandfather stopped him.

“That ain’t how you do it, baby,” his grandfather told him. “You’ve got to get it by the root. Because if you don’t get it by the root, it’ll grow back.”