This story was produced in partnership with WBUR. WBUR’s investigations team is uncovering stories of abuse, fraud and wrongdoing across Boston, Massachusetts and New England. Get their latest reports in your inbox.

You can listen to related reporting on this subject, which aired on the program “Here & Now.”

Devantee Jones-Bernier was spending an afternoon at a friend’s apartment in Worcester, Massachusetts, when police banged on the door, looking for drugs. They found marijuana in the unit, where several people had gathered, but not on the 21-year-old college student. Police took his iPhone and $95 in cash.

The district attorney’s office charged him and seven others in May 2014 with drug offenses, but later dismissed them against Jones-Bernier and all but one person. Despite that, law enforcement officials held onto his money and phone.

Under a system called civil asset forfeiture, police and prosecutors can confiscate, and keep, money and property they suspect is part of a drug crime. In Massachusetts, they can hold that money indefinitely, even when criminal charges have been dismissed. Trying to get one’s money back is so onerous, legal experts say it may violate due process rights under the U.S. Constitution. It’s especially punishing for people with low incomes.

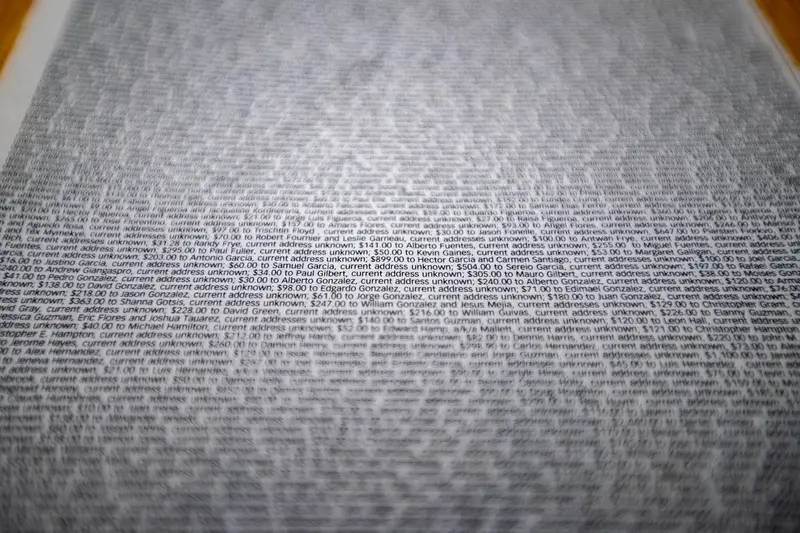

Four years passed before the Worcester County district attorney’s office tried to notify Jones-Bernier, as required by law, about the status of his money. The office ran a newspaper notice, three times over three weeks, listing Jones-Bernier’s name in tiny legal type alongside more than 100 others involved in separate seizures. The ads said the district attorney intended to keep their money, and those who wanted to fight back had 20 days from the final ad to respond in civil court.

Jones-Bernier had no clue about the ads so he didn’t respond.

Massachusetts is an outlier among states when it comes to civil forfeiture laws. Prosecutors in the commonwealth are able to keep seized assets using a lower legal bar than in any other state.

“It’s out of step with justice,” said Louis Rulli, a professor at the University of Pennsylvania who specializes in public interest law. “It produces unjust results and cries out for reform.”

Amid rising national attention to the issue, other states have rewritten their laws, and the U.S. Supreme Court recently ruled in favor of a man whose car was seized during an arrest on a small drug sale. But Massachusetts has not budged.

WBUR took an in-depth look at Worcester County, which ranks among the top counties for forfeitures in the state. An examination of all forfeitures filed there in 2018 found that of the hundreds of incidents, nearly 1 in 4 — or 24% — had no accompanying drug conviction or criminal drug case filing.

And that is likely conservative; another 9% of seizures had no publicly available court records, meaning there were no charges or courts sealed the records.

In an investigation with ProPublica, WBUR also found that Worcester County District Attorney Joseph D. Early Jr. regularly stockpiles seized money, including that of people not charged with a crime, for years, and sometimes decades.

In more than 500 instances between 2016 and 2019, WBUR found that funds had been in the custody of the DA’s office for a decade or more before officials had attempted to notify people and give them a chance to get their money back. One case dated back to 1990.

The yearslong delays raise “obvious due process concerns,” according to Sam Gedge, an attorney at the Institute for Justice in Arlington, Virginia, a nonprofit that has studied the issue and advocated for changes to forfeiture laws across the country. “The notion that you have the government waiting even two years — but certainly two decades — to commence forfeiture proceedings is, if not unprecedented, then extraordinarily rare.”

Gedge said the latitude granted to law enforcement in Massachusetts in civil forfeitures reflects broad problems with the system nationwide. In general, he said, “It’s much easier for the government to take your cash, your car, your home, using civil forfeiture than it is to prove your guilt beyond a reasonable doubt in criminal court.”

Early, in an interview, said his office obeys the law.

“We follow all the rules that the court gives us,” he said. As for the long delays in filing forfeitures, “We try and get these wrapped up as expeditiously as we can,” Early said.

But for hundreds of people in Worcester County, it’s been anything but expeditious. There’s no oversight by the state when it comes to how long district attorneys wait to notify people that, without a court fight, their money will stay in law enforcement’s hands. And there is no public reporting of criminal conviction rates tied to forfeitures.

In the absence of that information, WBUR set out to compile the data. To evaluate the county’s record, WBUR analyzed all the Worcester County forfeitures in 2018, a year chosen to allow sufficient time for related criminal cases to have concluded. The analysis included the review of thousands of pages of records in several courts and included forfeitures from 396 seizures.

Among those, there were more than 90 instances where people lost money or cars, taken most often during traffic stops, frisks and home searches — even though there weren’t related drug convictions or drug charges. Law enforcement still held onto the cash and property.

Civil forfeitures are big business in Worcester County, where Early has been the elected district attorney since 2006. His office brought in nearly $4 million in forfeitures in just the latest four years, from fiscal 2017 through 2020, according to analyses by the state’s trial court.

Where that money goes is notable. In almost all cases, the proceeds are split 50/50 between the Worcester County district attorney’s office and the local or state police department that handled the seizure. That’s legal in Massachusetts, but it’s a system rife with conflicts of interest because the offices confiscating the money also stand to benefit from it, lawyers and civil rights advocates say.

Early has been criticized by the state auditor for spending forfeiture funds on a Zamboni ice-clearing machine and tree-trimming equipment. Over the years, his office has posted photos on its website of Early handing out checks for “Drug Forfeiture Community Reinvestment,” to pay for baseball and softball fields or to support a cheerleading team.

Early said he’s proud that his office has spent large sums of confiscated money on youth programs and drug prevention. “I love taking the drug dealers’ money. I love taking their lifeblood and putting it back into the community,” he said.

But WBUR’s analysis shows many of the people who lose money to Early’s office are not charged with dealing drugs.

Preying on the Poor

While the system has evolved into a significant revenue source, it started as a remnant of old English law. Civil forfeiture was pioneered at the federal level in 1970, touted as a tool in the war on drugs. The idea was to financially weaken big drug dealers and gangs by allowing police to take their money, property and drugs.

When the drug forfeiture law was adopted in Massachusetts in 1971, it required prosecutors to show a “preponderance of evidence” to support a seizure. Specifically, they had to establish that seized property or money was “more likely than not” involved in a drug crime. In 1989, Massachusetts lawmakers eased the rules to the current “probable cause” standard, the least demanding burden of proof in the American legal system. Massachusetts was not alone at the time, but it’s the only state that in the intervening years has not reinstated a higher level of proof, according to an Institute for Justice report.

Police in this state can take money or belongings based merely on the reasonable suspicion that someone is involved in drug activity. Often police cite people appearing nervous, carrying rolls of $20 bills or traveling on what officers call a “well-known route used by drug traffickers” as the justification for seizure.

The U.S. Supreme Court in 2019 ruled unanimously on a civil forfeiture case, Timbs v. Indiana, that the state’s forfeiture of a man’s $42,000 Range Rover was unconstitutional. The court found that confiscating his vehicle was “grossly disproportionate” to the seriousness of his crime — the sale of $225 worth of heroin — and violated the Eighth Amendment protection from excessive government fines, as well as the 14th Amendment right to due process.

The Timbs ruling was cited this year in a case involving a Massachusetts woman whose car was confiscated for six years after police suspected it was connected to drug trafficking charges her son was facing. The son died before prosecutors finished trying the case. The woman faced no charges. The Berkshire County district attorney finally released the vehicle, after a high-profile legal group stepped in to sue the DA on her behalf.

In other New England states, people have a better chance of getting their belongings back from seizures.

Connecticut, New Hampshire and Vermont all require some form of criminal conviction for the forfeiture of property. And in Rhode Island, prosecutors must meet the preponderance-of-evidence standard. In federal cases too, the law has changed from probable cause to a higher standard of proof; the government must show that property is “likely” connected to a crime in order to forfeit it.

And Maine has gone a step further. It recently passed a bill to abolish civil forfeiture, becoming the fourth state in the nation to do so. The law now requires a criminal conviction before law enforcement can permanently take property.

The Massachusetts forfeiture law was originally intended to go after people involved in large drug rings. But Rulli, the University of Pennsylvania professor, said there has been a shift in how forfeiture is deployed at the street level, targeting people involved in petty crimes or marijuana sales, or no crime at all.

“This became a very lucrative area of revenue. And as a result it got applied to ordinary folks,” rather than focusing solely on drug kingpins, he said.

WBUR’s analysis of Worcester County forfeitures from 2017 through 2019 found that more than half of the seizures in these cases were for less than $500. In one incident, Fitchburg police seized $10 from a man listed as homeless. In another, Sturbridge police took $10 from a 14-year-old boy.

State Rep. Jay Livingstone, who represents the Back Bay, Beacon Hill and parts of Cambridge, is a former assistant district attorney for Middlesex County. He said civil forfeiture tends to disproportionately affect poor people, and he’s witnessed law enforcement “taking small amounts of money from people that really can’t afford it.”

After filing two unsuccessful measures to overhaul the forfeiture system in Massachusetts, Livingstone now has a third reform measure pending in the Legislature’s Joint Committee on the Judiciary that would require a conviction and provide legal counsel to the indigent.

Navigating the system to reclaim money is an enormous challenge, in part because forfeiture falls into a complicated, two-pronged legal track in Massachusetts.

First, police seize money under suspicion of drug activity and pass the matter on to the district attorney. The DA’s office, if it decides to file a criminal drug charge, generally does so within a few weeks in district court.

Separately, the DA files a forfeiture case in a different, civil, court system — typically the state Superior Court. The civil and criminal cases are not linked in court databases, adding to the complexity of navigating the system and making oversight of the outcomes difficult.

Beyond the opaque court process, those in charge of civil forfeitures — district attorneys and police — face little public accountability when it comes to seizing money from residents, and what happens to the confiscated cash and property.

The only public accounting of how the money is spent is the information DAs now must report to the state treasurer’s office, as part of the Legislature’s 2018 criminal justice reform. But those reports don’t disclose all the spending and are not itemized beyond broad categories, such as “other law enforcement purposes.”

A state commission formed in 2019 to study the forfeiture system had little luck obtaining more data from the DAs. During commission meetings, including one in June, officials said DAs had ignored their requests, as well as questions about how they collect and spend confiscated funds.

The commission recently released its recommendations to the Legislature, proposing a number of changes to check the power of law enforcement. Chief among them are raising the burden of proof for forfeitures and removing the financial incentive to keep seized assets, by requiring that the money be sent to the state’s general fund. The proposal also seeks stronger reporting to the state and a set minimum amount of money eligible for forfeiture.

Early said he has now adopted a minimum of $1,000 for civil forfeitures, a policy he updated a day after receiving WBUR’s questions and a week after the commission issued its report. But he defended past forfeitures of small sums, saying any alleged drug money is bad for neighborhoods.

“If I can get $5 or $10, $20, $50, $200, $50,000 or $100,000, it’s all going into my prevention efforts,” Early said.

Some of the commission’s proposed changes are likely to face opposition. Many in law enforcement argue that civil asset forfeiture helps take down major drug traffickers, stripping criminals of resources and destabilizing organized crime. And officers do find drugs in many instances, as they did in a 2018 case where Worcester police, along with members of a drug task force, busted a heroin distribution ring and seized $30,414 in cash.

Norfolk County District Attorney Michael Morrissey represented all DAs on the state commission. In one of its recent meetings, he said his office uses forfeiture funds to pay for extraditions and warrants. In a subsequent interview, Morrissey said he believes some of the commission’s proposed changes are reasonable, but warned that if those funds were to dry up, the Legislature “should start thinking about how much money they’re going to have to backfill my budget.”

Early said he relies on confiscated money to pay for investigations into drugs and human trafficking, for expert witnesses and witness protection. Without that money, he said, it’s possible his office would need the state to increase his budget.

He argued that there’s no conflict of interest in law enforcement keeping confiscated funds. As for raising the burden of proof to a preponderance of evidence, Early now says he’s for it.

In the DA’s Hands

None of the proposed reforms address how long a DA can hold seized funds. Money confiscated by police sits in limbo until the DA files a forfeiture case in civil court. Early’s office has amassed hundreds of thousands of dollars by routinely waiting years to file civil forfeiture actions, without notifying individuals of the status of their money and effectively holding it hostage until court proceedings commence. This includes the 500 cases WBUR found that lingered for more than a decade.

Early blamed police for being slow at times to turn over seized cash to his office, but did not name specific departments. He also said it’s his office’s practice to wait for criminal cases to conclude before filing civil forfeitures. That doesn’t explain the yearslong delays, however.

Legal specialists said waiting years, if not decades, to file forfeiture motions may violate an individual’s due process rights.

“It’s exactly what the framers of the Constitution were concerned about … a state coming in, depriving someone of their property and, really, you can’t do anything about it,” said Nora Demleitner, a professor at the Washington and Lee University School of Law. “It’s very hard, procedurally, the way this is set up, to act against [the state].”

Early disagreed with critics and said interested parties are provided an opportunity to respond in court. “In no way, shape, or form do we look at that as an infringement on people’s rights,” he said.

But last week, Early said he now plans to tighten the window for filing a civil forfeiture to within two years of a criminal case concluding.

Wyoming’s Supreme Court ruled last year that waiting even nine months to file a civil forfeiture case was too long. The court said the state attorney general’s office violated an Illinois man’s due process rights by delaying a forfeiture filing that followed a traffic stop. The man was never charged with a crime, and the state was ordered to return $470,000 seized from his trunk on an interstate highway.

The majority of states require DAs to take action within 90 days of a seizure or the conclusion of a criminal case. But in Massachusetts, there is no deadline for DAs to file a civil forfeiture action in court. The only legal obligation is that DAs must eventually notify people by mail or newspaper notice that they intend to keep property.

Many of Early’s delays reflect his stockpiling of cases. His office has a practice of combining dozens of unrelated incidents into large forfeiture cases. The long waits can mean people seeking to reclaim money never receive court notices, often because of outdated addresses.

In the last five years, the Worcester County DA packaged more than 1,270 people into 16 cases, involving more than $350,000, according to WBUR’s analysis. Nearly three-quarters of the seizures in these cases were more than three years old by the time the forfeiture was filed. In one instance, Early’s office folded more than 700 incidents into a single case.

Take, for instance, Commonwealth of Massachusetts vs. Twenty Eight Thousand Three Hundred Fifty Six Dollars Fifty Cents ($28,356.50) In United States Currency. At first glance, the sum seems to reflect proceeds from a substantial drug bust. But court documents actually list 109 separate names and seizures — including one as low as $11 — spanning nearly 20 years.

Among the names in this giant batch in 2018 was Jones-Bernier, whose $95 had been taken four years prior. He was listed in an ad the DA’s office ran in the Worcester Telegram & Gazette, as having no known address. Jones-Bernier didn’t know his name had appeared there until he was contacted by WBUR. He said Early’s office could have sent a letter to his home address, which was on his driver’s license at the time of the arrest.

“There’s no way they could have NOT found my address,” he said. “It seems like a lazy attempt to try to resolve an issue that they knew they created.”

Jones-Bernier never got his property back. DA Early declined to comment on the case.

Early said his staff determined it was “better to package” cases and deal with them as a large group in the interest of “judicial economy” — meaning it would cost his office more money to file each case individually.

Of more than 1,000 seizures included in forfeiture cases from 2017 through 2019, Early’s office returned seized money to only 16 people, according to data obtained through a public records request.

Early, 63, was a defense attorney for 17 years before becoming district attorney. Much of his life has been steeped in politics, both as the son of a longtime U.S. congressman and now as DA for the past 15 years. And he has faced controversy in his long tenure. Last year, the State Ethics Commission alleged that Early and an assistant violated conflict of interest law by having a state trooper alter an embarrassing police report involving a district judge’s daughter arrested for driving under the influence.

Early and his attorney have maintained he did nothing wrong. The case is ongoing.

On the campaign trail in 2018, an opponent grilled Early for his office’s use of forfeited money, including the purchase of official cars for him and an assistant and the $985 Zamboni.

That ice resurfacer was included in a 2013 report by the state auditor that found more than $50,000 in expenditures lacked adequate documentation on what law enforcement purpose they served. It flagged funding for such items as upkeep of tennis and basketball courts.

Early’s office defended the Zamboni purchase at the time, saying it was for city rinks where members of the county diversion program worked, and that the athletic court upkeep was for a summer youth program. State law permits district attorneys to use up to 10% of forfeited funds for drug-related rehabilitation and education programs if they “further a law enforcement purpose.”

The audit report said Early’s office lacked transparency in how forfeited proceeds were accounted for and distributed, and said it should better document confiscated funds “to ensure all case information is correct, it receives all the judges’ forfeiture orders, and local police departments properly account for funds in their possession.”

In a mandatory post-audit review a few months later, Early’s office told the auditor it was establishing procedures to improve tracking of forfeited funds, according to public records obtained from the auditor’s office.

The auditor has not followed up with the Worcester DA about these procedures since then. Early’s office said that after the audit, they asked police departments for an update on seized funds and now communicate with them “regularly.”

The Struggle to Get Money Back

In theory, anyone can fight to get their seized property back. But unlike in criminal cases, there is no right to a free, court-appointed attorney in civil forfeiture. For many people, it’s impossible to pay an attorney the several thousands of dollars it can cost to pursue their property. Often, a lawyer’s fees would exceed the value of the seized money.

Many people never try to get their money back. Some lack the language skills to wage a legal fight; others just want to avoid tangling with law enforcement. And then there’s the tight, 20-day, window to respond — among the shortest in the country, according to a WBUR review of state statutes. It leaves little time for a letter to be rerouted from an incorrect address, or for the property owner to hire an attorney.

As a result of these hurdles, the majority of civil forfeiture cases are ruled in the district attorney’s favor by default, meaning people took no action to get their money back. In Worcester County, 84% of forfeiture cases in fiscal 2019 were default judgments, according to data from the trial court.

Even when people do take action to get their money back, the district attorney may have other plans for it. One resident found that out the hard way.

Northbridge police and members of the Blackstone Valley Drug Task Force stormed into Laura Wojcechowicz’s house on a September evening as she was getting ready for bed.

“The SWAT came and … they barged right in and held the gun to my chest, told me, ‘Sit the f--- down, don't you f---ing move. Who’s in the house?’” she recalled.

Wojcechowicz, a 52-year-old grandmother, works part-time as a personal care attendant but said her hours were cut back because of the pandemic.

She didn’t know it then, but police were executing a search warrant. They suspected her partner of 30 years, William McPhail, was selling drugs from the home the two share.

She said the police told her, “We’re not here for you.”

But at least $4,800 that she says belonged to her ended up in the hands of the police, even though she was not a target of the investigation.

“There was money in the safe that was in a little wooden box. … It had a little lock and it was all $100 bills,” she recalled. “And I put it in there and I put it in Bill’s safe.”

On the evening of Sept. 30, 2020, law enforcement records show, police found the $4,800 in McPhail’s safe — alongside an unspecified amount of cocaine and heroin. Even though she did not personally face charges, to get the seized money back, Wojcechowicz would have to prove it belonged to her and that it had no connection to the drugs.

It was going to be a steep climb. Wojcechowicz, like anyone fighting a forfeiture in Massachusetts, was in essence guilty unless she could prove her innocence.

Early’s office sought and received a detailed accounting of her finances over a five-month period, according to emails reviewed by WBUR. She said the cash was a combination of state pandemic unemployment assistance, federal stimulus funds and money from her mother.

“She has produced all of her bank records,” said Joseph Hennessey, a Worcester defense attorney who is working on Wojcechowicz’s case pro bono. “She has produced all that, and they’re still not satisfied.”

Without resources and a lawyer, it’s virtually impossible to get one’s money back. “The indigent community doesn’t have the ability to fight for the return of the money, so they are the target. They lose out on all of these seizures,” Hennessey said.

And Early’s office has shown it doesn’t need to find drugs or file criminal charges in order to keep seized property. In court filings, the DA lists victories in such instances and cites them as precedent.

In some cases, district attorneys will accept a deal, according to interviews with seven lawyers who have worked on forfeiture cases in Massachusetts. Prosecutors will often drop criminal charges or seek lighter sentences, the lawyers said, if a defendant gives up all or part of the cash that was seized.

“One of the things that we would have to do in order to get someone a better plea deal was to sign off. Basically, my client would have to sign over their money,” said Arielle Sharma, an attorney with the Boston nonprofit Lawyers for Civil Rights and a former criminal defense attorney in Worcester. “It’s cash for freedom, right?”

After weeks of back-and-forth, Early’s office rejected the documentation Wojcechowicz had provided to show the seized money belonged to her. Her partner, McPhail, was facing two years in county jail. Wojcechowicz’s lawyer told her if she dropped the fight for her money, McPhail would have a better chance at less jail time.

A judge in the case said the forfeiture had to be resolved before he would sentence McPhail.

Wojcechowicz said she felt she had no choice but to agree to give up the money.

McPhail pleaded guilty to two counts of drug possession and another two counts of possession with the intent to distribute. He was in jail for 47 days, but avoided the rest of the term. He is currently on probation.

Early’s spokeswoman, Lindsay Corcoran, in statements said the office does often agree to “concessions” on charges, “but these are in no way linked to any forfeiture.”

In this case, she said there was no deal: “Our office is following the law and all forfeiture proceedings are ultimately decided by a judge.”

Since losing the money, Wojcechowicz’s finances have been tight. She said she’s had to think twice about her spending, even to fill the gas tank.

“It stops me from going to do stuff with my grandkids,” she said. “My mother helps me out a lot. It was a big hit.”

Rahsaan Hall, director of the Racial Justice Program for the ACLU of Massachusetts, said the state Legislature needs to adopt more protections for people like Wojcechowicz.

Hall, who served on the state’s civil forfeiture commission, said the recommendations before lawmakers are a good starting point. But he urged the Legislature to go further, by requiring a criminal conviction in order to keep someone’s money.

He said the state’s civil forfeiture laws, as they stand now, are “a stain on our identity.”

This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

WBUR investigations editor Christine Willmsen and senior investigative reporter Beth Healy contributed to this report.