This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Source New Mexico. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

On a recent sunny morning in the high pastures of northern New Mexico, Tito Naranjo greeted a pair of federal surveyors on a patch of gravel where his traditional adobe home once stood.

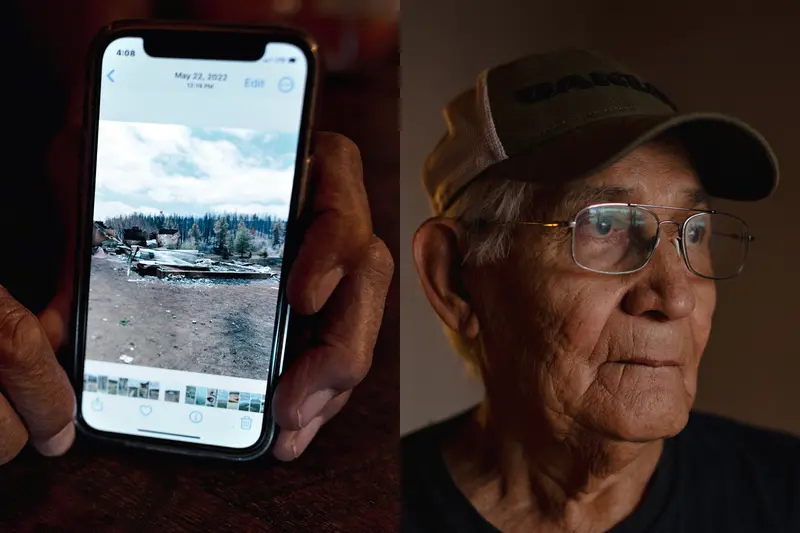

Naranjo used his walking stick to show them the outline of where his sunroom had been before it burned up in a wildfire accidentally set by the U.S. Forest Service last year. They walked slowly to the edge of the property, past a blackened willow tree that once held a tire swing, and stepped over a creek now empty of trout.

The tour confirmed what satellite imagery hinted at: This 97-acre property was a total loss. The home Naranjo and his wife had shared for 50 years, a stand of aspen trees, a small apple orchard, miles of fencing and a bridge he had built himself, all gone.

Naranjo, 86, hasn’t laid the first adobe brick of a replacement home, hammered a fence post or planted a single tree. And with congestive heart failure raising the risk of a stroke, he worries he won’t live long enough to do so.

Seventeen months after losing their homes and livelihoods in the Hermits Peak-Calf Canyon Fire, Naranjo and thousands of others in the aging, rural communities in New Mexico’s Sangre de Cristo Mountains are still waiting for money to rebuild.

As the fire swept across the mountains for five months in mid-2022, the Federal Emergency Management Agency responded as it would to any disaster. It provided roughly $6.2 million to about 1,100 households for short-term expenses like housing and evacuation and, in some cases, for limited damage to housing and possessions.

But even for people who lost everything, those payments were capped at about $38,000. Most people got far less, and some got nothing. Few people were given temporary housing. Farmers and ranchers are struggling to earn a living.

The money for the far more difficult and expensive task of rebuilding is supposed to come from a $4 billion fund set up by Congress just for this fire — an acknowledgment of the Forest Service’s culpability in triggering the blaze. But the FEMA office handling those payments didn’t start sending checks as quickly as expected, and it has yet to spend 98% of the money.

FEMA has defended its rollout of the claims office, saying it is moving as fast as a federal agency can. Normally, FEMA offers only short-term disaster aid. This is only the second time it has been tasked with paying survivors so they could rebuild after a federal agency lost control of a prescribed burn meant to prevent a wildfire. FEMA established policies, hired staff and opened offices in eight months.

Faced with delays in getting paid and questions about what FEMA will ultimately cover, a local attorney representing Naranjo and several hundred other survivors recently convinced a federal judge to allow some of her aging, infirm clients to testify under oath about what they have lost — an unusual move intended to preserve knowledge that their relatives don’t have.

Antonia Roybal-Mack, the lawyer, said she wants to make sure these victims are made whole if they die before they get a check from the federal government. If they end up filing suit to get what they believe they deserve, “these clients will likely expire before they get their day in court,” she said.

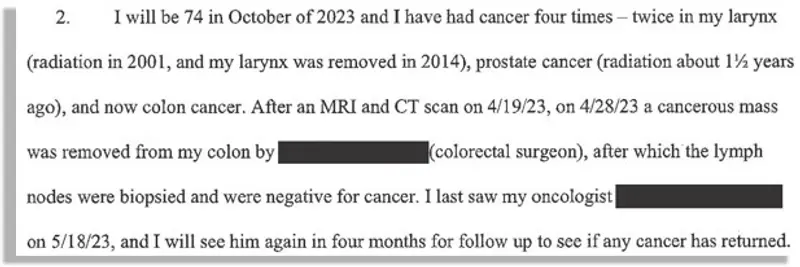

Her clients include farmers and ranchers who lived off land that was burned in the fire or that was washed out in the floods that followed. According to sworn court filings, they include a Vietnam veteran who said he was “blown to hell” in the war, a salon owner who said her doctors told her that her recent lung disease came from “chemicals and smoke,” and a former police chief who recently was treated for cancer for the fourth time.

Many survivors have lived in these tight-knit communities for decades, some their whole lives. Their way of life — captured by the Spanish word querencia, which people here use to express their love of the land and their obligation to it — was under threat even before the megafire. Naranjo is one of the last fluent speakers of Tewa, the language spoken in the Indigenous pueblo he grew up in. The population of Mora County, where he now lives and one of two counties that were badly burned, declined 15% from 2010 to 2020, to about 4,200, according to census figures.

Now living at his son’s home two hours away, Naranjo is trying to figure out what, if anything, he can do for his land. His wife, Bernice, said the instability of life since the fire and their sudden reliance on the government has made his final chapter distressing and chaotic.

“He doesn’t show his emotions very clearly, but he does feel the loss tremendously,” she said. “And he knows that he may never be able to rebuild.”

Before a Check, the Fine Print

The $4 billion Congress set aside is supposed to compensate survivors, businesses, local governments and nonprofits for damages in the 534-square-mile burn scar. But the claims process is long and complicated, and the vast majority of victims haven’t gotten anything yet.

FEMA wrote its first check to a survivor in June, according to the claims office. That’s a year after the fire raced through the mountains. As of Sept. 15, it had paid $67 million, just under 2%, most of which went to individuals. The pace has picked up in recent weeks, however. (New figures are expected next week.)

Though the Forest Service said 430 homes burned in the fire, a maximum of $2 million has gone to housing as of Sept. 15, according to FEMA’s figures. FEMA said it is processing “a fairly small number” of claims for housing, though officials have declined to say exactly how many.

The problem is twofold: Some people held off on filing claims as they waited months for FEMA to finalize its rules on exactly what it would pay for. And for those who did file, the checks have not come quickly.

Source New Mexico and ProPublica spoke to about 30 survivors about the claims process. A little under half said they had not yet filed a claim. They said they were desperate to start rebuilding but needed clarity on the claims process.

Until late August, the claims office operated under interim rules largely copied from the Cerro Grande Fire in 2000 — the only other time FEMA has paid for damages for a wildfire accidentally started by the federal government. FEMA officials acknowledged differences between the fires but said they started with those rules because they were in a rush to get moving.

Some of those residents told us they didn’t want to file claims under those rules, believing they would miss out on additional money if the final rules were more generous. FEMA officials told survivors that would not happen, but lawyers and residents told Source and ProPublica they feared that the formulas in the interim rules would determine their payments regardless.

A big sticking point was the value of the trees that once covered these mountainsides. Residents and lawyers said the interim rules undervalued those trees, which are harvested for timber, Christmas trees, and latillas and vigas — ceiling rafters commonly used in Southwestern homes. While the claims office issued partial payments for other damages, it held off on paying for trees until it could figure out how to value them.

The final rules released on Aug. 28 offered far more for trees than the interim rules, which finally assuaged those concerns. Based on that formula, Angela Gladwell, the head of the claims office, said she expected tree losses to top $1 billion.

Residents who didn’t wait for the rules to be finalized faced different obstacles. After a claim is filed, FEMA must formally “acknowledge” it. But FEMA has no deadline by which that must happen. The agency started encouraging people to file claims in November, but none were acknowledged until April. The delays continued through the summer.

FEMA told Source and ProPublica that it tries to acknowledge claims within 30 days, but that it took time to create a new office and train staff. The agency also said its office had at times received a lot of notices at once, which delayed the process.

The claims office is catching up: As of Sept. 14, it had acknowledged about 80% of the 2,214 claims filed. But those survivors face a new round of waiting. Once FEMA acknowledges a claim, it has 180 days to make an offer to pay for those damages. People can decide to take the money or to fight for more through arbitration or in federal court.

The pace of payouts is slower than it was for the Cerro Grande Fire. After a similar amount of time since a law went into effect to compensate those victims near Los Alamos, FEMA had paid about $162 million out of $545 million allocated — about 30%. That included about $84 million to individuals.

FEMA says payments are taking longer this time because this fire was bigger, the communities are poorer and have less insurance, and the claims are more complex, with agricultural and ranching losses to consider along with burned homes.

The agency plans to distribute $1 billion — a quarter of the total allocated — by January 2025. It did meet a recently set internal target of spending $50 million by Oct. 1, a spokesperson pointed out.

Regardless of whether they have filed a claim yet, survivors face uncertainty over whether all their costs will be covered. People who accept a payment must sign a form saying they won’t seek additional compensation or sue the government for “past and present and future claims” for the category of loss they’re being paid for. But more than a year after the fire was extinguished, people don’t know if they’ve seen the last of the damage.

The fire burned root systems and topsoil, creating a landscape where dirt and debris sloughs off the mountainside when it rains, particularly after spring snowmelt and during the summer monsoon season. That’s expected to continue for several years.

Since the fire, “I’m constantly doing flood control and mitigation,” said Felicia Ortiz, whose hillside property is eaten away during rainstorms. FEMA acknowledged her claim on Aug. 18 and has yet to pay her.

She estimates she’s spent roughly $8,000 on recovery, much of it to divert floodwaters. “Cleaning up messes from the flooding — it happens, you clean up, it happens again, you clean up again.”

Despite the form that survivors must sign, FEMA says victims like Ortiz need not worry about ongoing damage after they’ve accepted a check. Any loss that occurs afterward could be eligible for reconsideration, the agency says; Gladwell, the claims office head, has sole discretion on whether to reopen a particular claim.

All these obstacles leave some fire victims wondering whether they can trust the federal government that burned their property, denied short-term aid to many of them and then promised to make them whole.

“I do believe that Angie Gladwell is really trying to serve the people,” said Kayt Peck, who waited until the final rules were released to file a claim for her destroyed home. “But she’s just one cog in the FEMA wheel. And when you’re working with someone that you know from the past that you couldn’t trust, and they’re telling you to trust them, don’t trust them.”

FEMA has stressed that the claims office is separate from the program that provided limited assistance when people were fleeing their homes. Staffers with the claims office regularly show up at community events, handing out brochures encouraging people to file claims. The claims office advocate holds meetings to combat “half-truths and misinformation” about what FEMA will and won’t pay for.

“We know that trust is earned by doing what we say we are going to do, and delivering results,” FEMA spokesperson Deborah Martinez said.

A Year of Waiting

Most of the people who spoke with Source and ProPublica said they can’t rebuild before FEMA pays their claim. Few of those displaced by the fire had insurance. Some said they’ve already spent their temporary aid; others never got any.

A state agency said in February that people are leaving for urban areas such as Albuquerque and won’t be able to return without financial help. Calls from fire victims to a mental health hotline shot up this spring. And in August, U.S. Sen. Ben Ray Luján greeted President Joe Biden on a visit to New Mexico by handing him a letter criticizing delays in payments.

New Mexico Gov. Michelle Lujan Grisham said on a recent visit to the burn scar that the message from FEMA is to wait, just as it was last summer: “That’s what you’re hearing from everyone: ‘I don’t know what I’m supposed to do. I’m waiting.’”

Martinez, the FEMA spokesperson, said the claims office recognizes that the recovery “has been a uniquely challenging and often frustrating experience for many,” and it is providing “unwavering support” to survivors.

FEMA has partnered with other federal agencies to help survivors. A Department of Agriculture program provides free estimates for some types of losses. FEMA will pay up to five years of flood insurance premiums for those expecting post-fire flooding. And the claims office recently announced it would pay survivors’ Small Business Administration disaster loans, including interest.

Brian and Nell Rodgers lost not just their home on a hilltop 5 miles east of Hermits Peak, but their carefully planned life of self-sufficiency. They raised trout in an indoor pond. Brian had converted a few vehicles to run on biodiesel; when the waste vegetable oil he was processing into fuel exploded during the fire, he said, it could be seen for miles.

They put their disaster aid toward an RV and moved to Santa Rosa, 80 miles away in the desert. For six months, the couple “itemized every detail of our life” in anticipation of a larger payout, said Nell Rodgers, a 70-year-old retired schoolteacher. They filed their claim in July. The claims office acknowledged it quickly, but the money has yet to arrive.

When Nell experienced chest pains after a surgery in July, she wanted to go to an emergency room in Santa Fe, more than an hour away. Because they were short on cash, Brian Rodgers had to ask his ex-wife, who lives nearby, for $20 in gas money.

The government “took away our retirement — and took away our possibilities,” Nell Rodgers said. “And so now, the only thing we can count on is compensation. And that doesn’t seem to be coming anytime soon.”

Sam Arthur, the owner of a clothing boutique in Las Vegas, New Mexico, lost the home he shared with his wife, Tamara Fraser, in April 2022 — the day the fire suddenly surged across the mountains. Dozens of homes were destroyed in one day.

He said he promptly received the maximum amount of emergency assistance, but it was nowhere near enough to repair his home or restore his acres of scorched property. He submitted a notice of loss to FEMA on Jan. 6, seeking to be paid for the destruction of his home, relocation costs, debris removal, cleanup and other expenses. The agency didn’t acknowledge his claim until Sept. 1. Under the rules, it has until the beginning of March to make a payment offer.

In the meantime, he and his wife are living in a “tiny home” on wheels in the parking lot behind his store. “At least it’s ours, and we don’t have to pack up and leave again,” he said. “Those things were starting to take a toll.”

Neighbors Step Up

While victims wait, they’re getting help from a local volunteer group that has raised funds to pay for essentials like refrigerators, generators and wheelchair ramps.

Neighbors Helping Neighbors got its start when Janna Lopez, a retired state worker, began bringing hot food to a shelter at a former school gym as the fire raged in April 2022. After the fire was contained and survivors’ needs grew more complex — unpaid rent, flooded driveways, contaminated wells — she and fellow volunteers kept at it.

By July, the organization had handed out about $300,000 to about 65 households — about as much as FEMA had provided to households by then, said Bob DeVries, a volunteer and track coach at the local university. (Since then, FEMA has increased its payments.) Now, payments from the volunteer group are approaching $500,000.

Every Thursday, the group’s two case managers gather at a local church with representatives of four local religious and philanthropic organizations. They decide how much to give each victim, no strings attached, typically capped at $12,000.

One day in early August, they handled “Case 260,” a man in his 60s. His refrigerator was damaged when the power had been shut off, and the ojito, the natural spring he used for farm animals, was destroyed by flooding.

He didn’t have insurance, and his claim hadn’t been paid yet. He had gotten just $800 in disaster aid. “He’s, in essence, exhausted what he can get from the federal government,” said Chip Meston, who runs a local beef processing plant and represents one of the churches.

The committee quickly agreed to pay the entire request: $3,068.55.

Though the immediate crisis has passed, the number of people seeking help hasn’t dropped. There are about 45 active cases, with a backlog of more than 270. About 20% of households in the area were below the poverty line before the fire, and if they got any short-term aid from FEMA, it’s long spent, DeVries said.

Rosie Serna, 75, said Neighbors Helping Neighbors pulled her out of despair. She’d gotten by on Social Security since her husband died. The fire took the home where she hosted big outdoor gatherings for kids and grandkids.

For a while, FEMA helped her with rent as part of its disaster aid, but it stopped after she accepted temporary help from an aid group. By April, the $700 rent came due. She had no way to pay. She felt overwhelmed.

“I was just thinking of so many things: ‘Why me?’ ‘What am I going to do?’” she recounted, moved to tears. “And I said, ‘Maybe it’s better if I just don’t exist anymore.’ I thought, ‘Nobody cares about me.’ I felt so alone.”

One day in early April, Serna got a call from Gloria Pacheco, a retired schoolteacher and volunteer who was checking on her FEMA case. Serna seemed to have lost hope.

Worried, Pacheco drove 45 minutes to see her, the first time they had met in person.

After a long conversation, Pacheco connected Serna to a therapy service for fire victims, which Serna said has been helpful. Neighbors Helping Neighbors gave her a few hundred dollars for propane.

FEMA recently denied Serna’s appeal for rental assistance, but Pacheco said she’ll keep trying. Serna calls Pacheco “my angel.”

“I Really Have to Prepare”

As Naranjo waited to be sworn in for his deposition in a hotel conference room on July 20, he glanced at his watch. “We’re running 21 minutes behind,” he said to the lawyers gathered to question him.

Over the next two hours, he testified about the life he and his wife had built near their childhood pueblos, the monstrous fire that made ash of his journals, FEMA’s denial of any short-term aid, the future of his land.

“Is it your goal to restore the property as best you can to the way it was before the fire started?” asked Roberto Ortega, an assistant U.S. attorney.

“That can never happen,” Naranjo answered. “I would like to see it, but I saw it in its glory. It was a paradise. That paradise can never be rebuilt.”

As he prepares to leave his land and any compensation he ultimately receives to his wife and children, he’s made his priority the 3-mile fence that once encircled his property. He’s tired of his neighbor’s cows eating his grass for free. Most of all, he wants a permanent demarcation of what he will leave behind.

A few days after the deposition, he walked his property with Department of Agriculture employees to assess the damage. “I really have to prepare. You need to have permanent markers on it, so people know where your boundaries are,” Naranjo told them. “That’s why I want the fence. That’s my priority. Because my children don’t know the boundaries of our property.”

But rebuilding the fence, as with everything else FEMA has been involved with, isn’t as simple as he hoped. If he wants the full replacement cost, he’ll have to prove the fence was his by submitting affidavits from his neighbors or receipts — for a fence he built himself, 50 years ago, with timber from his property.

Back then, he felt energized by the land, waking early to run a 7-mile loop around the property and occasionally discovering prayer shrines left by early Pueblo peoples. Now everything is exhausting — walking up the washed-out road, dealing with the fence, hearing his kids’ ambivalence about whether they want to rebuild.

“I just haven’t got the strength, or the energy, or the outlook, or the dreams that I had at the time,” he said.

He no longer plans to have his remains spread on the property. He once envisioned his ashes scattered among the aspens and ponderosa pines. Instead, blowing through those blackened trees will be ashes of the paradise he lost.