Dena Sue Patel couldn’t hide her desire for a teenager at the youth treatment center in northern Indiana where she worked as a supervisor, according to court records.

Patel, 50, allegedly used her key fob to enter a 19-year-old resident’s living area at Pierceton Woods Academy on her days off and took him on private walks. Patel told the boy, “I’ve been wanting you,” and had sexual contact with him, prosecutors have alleged, and she admitted to being in a “romantic” relationship with the boy in a text message to a co-worker.

In August, Indiana prosecutors charged Patel with sexual misconduct and she pleaded not guilty. It was the third time since 2019 that police or child protective services formally accused a female staffer at Pierceton Woods of sexual abuse or misconduct involving residents.

In response, the state’s Department of Child Services temporarily stopped referring children to Pierceton Woods, which treats boys for substance use disorders and sexually harmful behaviors.

That lasted 11 days.

DCS lifted the hold after Pierceton Woods leaders committed to train staff and supervisors on appropriate boundaries and warning signs of abuse. Since then, DCS has accelerated referrals to the 48-bed facility, according to a spokesperson for Lasting Change Inc., a faith-based nonprofit that manages the facility.

This isn’t the first time the state has sent children to Pierceton Woods despite having evidence in its own files that they might not be safe there.

Since 2017, DCS has received at least 27 reports alleging sexual abuse or inappropriate behavior by staff at Pierceton Woods, an investigation by IndyStar and ProPublica found. In interviews and sworn depositions, former employees have identified more than a dozen female staffers they suspected of grooming or sexually abusing teenage residents.

Some of the allegations of abuse had previously come to light, but a deeper examination shows how widespread the accusations were and how a lack of oversight left residents vulnerable.

The news organizations found that Pierceton Woods managers and staffers ignored signs of abuse. In at least one case, state records show, an employee was able to abuse a resident even after supervisors were made aware of concerns about her conduct.

DCS has the authority to require the academy to submit plans of correction, temporarily stop sending children to the facility or even sever the relationship entirely. But the agency has done little to crack down on Pierceton Woods, which sits in a quiet wooded area about 30 miles northwest of Fort Wayne.

For example, after finding that Pierceton Woods failed to report abuse to DCS in 2020, agency officials required the facility to revise its guidance for employees. But the revisions that DCS approved contained no significant changes, and child-welfare experts said both versions of the policy may violate Indiana’s mandatory reporting law.

Even when Pierceton Woods did report suspected abuse, DCS didn’t investigate many of the reports. And in at least two cases, records indicate that the agency declined to look into allegations against staffers who were later found by police or a subsequent DCS investigation to have abused residents.

Over the last seven years, DCS has sent tens of millions of taxpayer dollars to companies managed by Lasting Change, which has deep political connections in Indiana. Among its supporters: Mike Pence, the former vice president and state governor.

DCS declined requests to interview agency officials, including Director Eric Miller, who was appointed by Gov. Eric Holcomb in May. Spokesperson Brian Heinemann did not answer reporters’ detailed questions about Pierceton Woods, saying confidentiality laws prevent the agency from addressing its involvement with children and families.

But in a statement, he said: “The safety and well-being of each child in DCS’ care is our top priority.” Heinemann added that people who suspect child abuse or neglect should immediately report it to the agency or call 911.

Lasting Change, which is based in Fort Wayne, provides a wide range of child services across the state through its Lifeline Youth & Family Services, one of DCS’ largest contractors. Officials for Lasting Change declined requests to interview CEO Tim Smith and did not answer questions about specific abuse allegations at Pierceton Woods, citing client confidentiality rules and employee privacy.

The company has denied failing to protect minors from sexual abuse and, as alleged in a former resident’s lawsuit, covering up allegations.

“We always report allegations, regardless of potential severity, and act upon them with speed, transparency, and in full cooperation with DCS,” company spokesperson Curtis Smith, who is not related to Tim Smith, said in an email.

Curtis Smith defended the facility’s track record and said reporters’ questions concerned “a very small number of clients and co-workers over a 55-year history.” The facility complies with DCS procedures and submits its policies to DCS for review annually, he added.

“We’re proud of our historical success serving these boys, but it is hard; their experienced trauma is great. The pressure on our staff while treating these boys is great,” he said. “We continue serving them today, but false accusations from any source are affecting our ability to continue serving these boys.”

Lasting Change also remains proud of its success as a business fueled by government money. At a ribbon-cutting ceremony this June, the chief executive offered thanks to DCS.

“There have been few times in 50 years when we’ve had more kids,” Tim Smith told a group of supporters celebrating the opening of a new greenhouse. “So from a business perspective, we’ve never done better.”

“Assembly-Line” of Abuse

The first known allegations against Darby Ellis, an independent living specialist at Pierceton Woods, came in 2017.

The report to DCS was screened out — deemed not worthy of investigation — because the resident had turned 18 prior to the report being made. This is a common practice among child welfare agencies but it can put children at risk if there is, in fact, a predator in the workplace, child welfare experts said. Some states allow investigations for youths age 18 or older under certain conditions.

Following the 2017 allegation, Ellis was asked to take a polygraph test, and she declined. Two years later, she was promoted to a position that allowed her to take residents on unsupervised trips off campus.

It wasn’t the last time DCS or Pierceton Woods missed an opportunity to protect children.

Suspicion arose again around Ellis in 2019. Security camera footage captured her in a “full frontal hug” with one boy, employees told DCS, and video showed Ellis and the same resident walking away from the facility, toward the soccer field, where there were no cameras. The resident had placed his hand on the small of Ellis’ back. Supervisors were aware of the footage, according to DCS records.

A manager even advised Ellis not to be alone with residents “due to some rumors that were going around,” but the facility did not report Ellis to DCS for another week.

In the meantime, Ellis was allowed to take two residents to dinner and a movie in Fort Wayne, where she “made out” with one of the teens, the two residents later told investigators.

Alexandra Chambers, then a youth treatment specialist, advocated for reporting the incident to DCS.

In an interview with ProPublica and IndyStar, she said that Pierceton Woods had problems both monitoring employee-resident interactions and quickly reporting suspicions of inappropriate behavior.

“All the employees knew of areas that didn’t have cameras,” Chambers said. “Everybody knew where the blind spots were.”

When she first became concerned about Ellis, Chambers said she hesitated to inform her managers because she feared they would dismiss her concerns as hearsay. “It was already known to me that they basically weren’t going to take the proper steps,” Chambers said.

One of the boys from the Fort Wayne trip then told Chambers that he had been abused by Ellis, and Chambers reported that conversation to a supervisor. The supervisor told the director of operations, who said in a deposition that he took it to the head of case management. Only then was a report made to DCS.

DCS investigators were told by one teen that Ellis gave him lollipops and performed oral sex on him. A 16-year-old said she took him to the facility’s soccer field, where she “made out” with him and they groped each other.

DCS determined that Ellis had what she called her “circle of trust” with three boys, allowing them to “do or say anything to her without consequences,” and it found that the abuse allegation involving the 16-year-old was substantiated. An allegation is considered substantiated if there is a “preponderance of evidence” that abuse took place.

Ellis was fired. And the 16-year-old’s family sued Pierceton Woods, alleging that the facility was responsible for allowing Ellis to abuse the boys then covering it up.

Kristine Chapleau, a psychologist hired by the boy’s family as part of the lawsuit, reviewed allegations against Ellis and found that Ellis “had groomed and abused these boys in an assembly-line fashion.” Chapleau also concluded that Pierceton Woods “maintained a culture of silence to suppress reports of sexual abuse.”

Smith, the spokesperson for Lasting Change, dismissed the psychologist’s assessment as one-sided because she was a paid expert for the plaintiff.

Lasting Change settled the lawsuit last year for $72,000. As part of the settlement, the teen was prohibited from discussing the case publicly and Pierceton Woods admitted no wrongdoing.

Ellis, then 25, denied the accusations to DCS and, in a deposition, disputed the characterization of a circle of trust. She did not respond to inquiries from reporters.

Police referred the allegations to the Kosciusko County prosecutor’s office. Ellis was not charged. The county prosecutor declined to comment.

DCS Failed to Crack Down

An examination of DCS’ investigations into Pierceton Woods shows the agency finding problems but not always fixing them — or sometimes standing by as the same problems reemerged.

During a DCS licensing audit in August 2020, the agency found that Pierceton Woods knew about suspected sexual abuse but failed to report it.

Pierceton Woods “has had multiple reports to the DCS hotline alleging staff and youth inappropriate and/or sexual relationships,” the audit said. “The majority of these reports were not reported” by the facility.

In several instances, the audit said, Pierceton Woods staff were aware of the allegations and conducted interviews with staff and youth “but did not make a report to the DCS hotline.”

To fix the problem, DCS required Pierceton Woods to revise its reporting policy to better align with Indiana’s mandatory reporting law, which requires abuse to be reported to DCS or law enforcement immediately and prohibits facilities from imposing policies that delay reporting. The audit said the revisions were supposed to ensure the agency reports “all suspected abuse and neglect to the DCS hotline prior to completing any internal interviews.”

But the revised policy DCS approved still required employees to report suspected abuse to supervisors before DCS or police. It also gave the facility 24 hours to report abuse — a much larger window than the four hours the state’s high court ruled was too long in another case.

In fact, the Indiana attorney general’s office argued in a case involving USA Gymnastics that its 24-hour policy “falls short of the requirements imposed by Indiana law … as well as what is necessary to protect athletes and children across the nation from abuse.”

DCS did not answer questions about why it approved the Pierceton Woods reporting policy.

Even when Pierceton Woods did report abuse to DCS, emails disclosed in the civil lawsuit show the agency often failed to investigate.

Indiana law requires DCS to investigate “every report of known or suspected child abuse or neglect the department receives.” But the agency screens out reports if they don’t meet the statutory definition of child abuse or neglect, or if there isn’t enough information to locate the child.

DCS does not provide numbers or records that would show how often it screens out reports for individual facilities. However, emails between staff at Pierceton Woods and the state licensing department offer a window into the practice.

DCS screened out at least 17 reports of suspected abuse by staff members at Pierceton Woods from 2017 to 2021, an examination of the emails shows.

The emails also show that, in addition to screening out the 2017 allegation against Ellis, DCS screened out a 2020 allegation against youth treatment specialist Kaitlyn McCullough. In June of that year, Pierceton Woods reported to DCS that one resident claimed another resident — who was under 18 — had an “inappropriate relationship” with McCullough, then 24.

The emails do not indicate the reasoning for screening out that allegation. DCS declined to comment.

Three weeks after the original allegation was set aside, Pierceton Woods submitted another report involving McCullough and the same resident. This time, the resident had shared Facebook messages between himself and McCullough in which they “professed having feelings” for each other, according to a July 8 email from Pierceton Woods to DCS’ residential licensing unit.

The boy also said he and McCullough had kissed.

Only then did DCS investigate, ultimately leading to criminal charges against McCullough. It is unclear from the emails and court records whether any abuse occurred during the 19 days between the first and second reports to DCS.

Court records show she admitted communicating with him over private Facebook messages and that they kissed and groped each other. She pleaded guilty to two misdemeanor counts of obscene performance as part of a plea deal.

McCullough’s lawyer said abuse allegations were “neither proven or agreed to” by his client, even though the charge to which she pleaded guilty, obscene performance, is considered “child abuse and/or neglect” under Indiana’s child welfare statutes.

Melinda Gushwa, a child welfare researcher and former child protective services investigator in California, said the state needs to examine the culture and climate that has produced so many reports of abuse. Given the history of Pierceton Woods, she would expect more involvement from the state.

“It’s concerning,” said Gushwa, who now leads the applied social sciences department at Technological University of the Shannon Midwest in Ireland. “We should have a higher level of scrutiny when we’re talking about vulnerable children.”

“Designed to Impede Reporting”

Indiana’s mandatory reporting law is intended to protect alleged victims from any additional abuse and prompt a quick investigation before evidence is lost or contaminated, and courts have found that even waiting a few hours to report concerns to authorities can be a violation. For institutions such as Pierceton Woods, the law also prohibits policies that restrict or delay an employee’s duty to report.

But a 2021 copy of the facility’s reporting policy obtained by reporters prioritizes reporting suspected abuse to company supervisors over DCS or police.

“The direct care staff are obligated to make sure that the first person informed of any allegation is the Program Manager/Coordinator,” the policy says. The sentence is the only one underlined in the five-page reporting policy.

Three child-safety experts said reporting policies like the one at Pierceton Woods defy best practices and may violate the law.

“It seems designed to impede reporting,” said Yvonne Smith, a professor at Syracuse University in New York who studies youth residential care and reviewed the policy at the request of the news organizations. “I mean, this document is horrible. I would throw this in the trash and start over.”

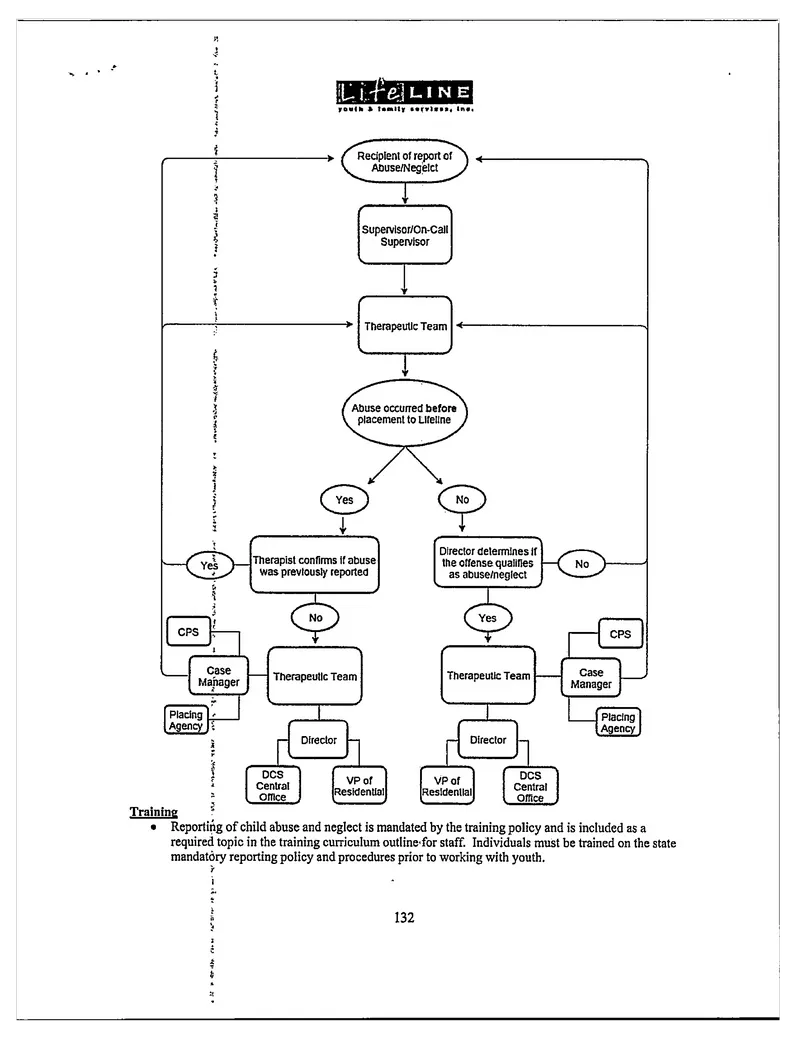

Pierceton Woods’ policy also included a flowchart that shows reports of suspected abuse passing through several layers of staff, including supervisors and officials who are described as directors. The director, according to the flowchart, “determines if the offense qualifies as abuse/neglect” before it is reported to DCS.

But it’s the role of DCS or law enforcement, not employees at the facility where the alleged abuse occurred, to investigate allegations, said Toby Stark, an expert on child abuse prevention who in 2017 was tapped to lead SafeSport at USA Gymnastics after revelations that the organization’s policies had failed to keep athletes safe from sexual abuse.

In general, Stark said, supervisors are prone to dismissing reports because of potential reputational harm to the accused or the organization. Sometimes, she said, supervisors just have a hard time accepting that sexual abuse could be happening at their workplace.

“How many times will a supervisor unwittingly, unknowingly — not maliciously — talk a person out of reporting?” Stark said.

Curtis Smith, the Lasting Change spokesperson, would not confirm whether the policy remains in place.

Former employees said the policy deterred reporting. While the policy required staffers to go to their supervisors, they often found those supervisors skeptical of abuse allegations. At least three former employees said supervisors didn’t take allegations of abuse seriously unless a staff member witnessed it or a resident told a staffer directly that they were abused.

Experts said that’s not the way mandatory reporting is supposed to work. Indiana’s law doesn’t require firsthand information. It simply requires a “reason to believe” that abuse has occurred.

Kat Manteufel, a former Pierceton Woods youth treatment specialist, said in a sworn deposition that she had heard about a staff member groping a resident. But she said she didn’t feel confident the situation would be handled appropriately if she followed the facility’s reporting policy.

“According to the handbook that we had, we were told to follow a certain chain of command,” she said. “Well, when I started realizing that nothing was going or getting past the direct supervisors, I went over all of their heads and called the DCS hotline.”

About two weeks later, she was fired, she said.

“They told me that they felt like they couldn’t trust me, and that I violated policy,” she said in a deposition for the lawsuit brought on behalf of the 16-year-old who said Ellis abused him. “I assume that I was fired because I called DCS instead of following the appropriate chain of command policy.”

Lasting Change did not answer questions about Manteufel’s termination, but Smith, the company’s spokesperson, emphasized that some of the complaints about Pierceton Woods in depositions came from former employees “who were either subject to discipline or were terminated.”

“We’re Still in Business”

Beyond Pierceton Woods, Lifeline Youth & Family Services, another Lasting Change organization, provides DCS with a multitude of services: home-based welfare, family preservation, and adoption and guardianship support services.

Together, Lifeline and Pierceton Woods have received about $250 million from DCS since fiscal year 2017, according to state spending records.

Much of Lifeline’s growth took place when Pence was running the state. As governor, Pence spoke at a fundraiser for one of Lasting Change’s companies, Crosswinds Counseling. Pence also named Lasting Change’s former longtime CEO Mark Terrell to a committee that nominates judges for Allen County, home to Fort Wayne. A former Lifeline official served as chief of staff to Karen Pence during her husband’s term as governor.

In a statement, a spokesperson for Mike Pence said Pence was unaware of the sexual abuse allegations at Pierceton Woods.

“ProPublica provided no evidence that Mike Pence had any role in Lifeline’s growth as a state contractor,” the spokesperson said in an email, “yet are still dragging him into a story that encompasses a time period during which Mike Pence was not even governor.”

The growth has benefited Lasting Change’s leaders. Terrell’s compensation increased 73% from $251,883 in 2015 to $435,600 in 2021, according to Lasting Change’s tax filings.

Tim Smith, who succeeded Terrell as CEO last year, also has ties to the Republican Party. In 2019, he ran as the Republican candidate for mayor of Fort Wayne and lost. Now, he’s running for Congress. In a recent campaign video, he described himself as a businessman and touted his work as the leader of “the largest Christ-centered family services provider in Indiana, fighting to protect kids and lift up families.”

Earlier this year, the company turned to Indiana’s Republican-controlled legislature for help. As a result of the lawsuit by one of Ellis’ accusers, Pierceton Woods’ annual insurance premiums skyrocketed from $30,000 to $500,000, according to Smith, a former insurance executive.

He made that disclosure while lobbying state lawmakers for a proposal that would have given DCS contractors such as Pierceton Woods and Lifeline immunity from many kinds of lawsuits.

During hearings on the proposal, Smith and Lifeline’s lobbyist, Brian Burdick, repeatedly referred to the 16-year-old’s lawsuit as a “nuisance” case. (Travis McConnell, the attorney for Ellis’ accuser, has rejected that characterization.)

Neither Burdick, Lasting Change CEO Smith nor Terrell disclosed during their testimony to lawmakers that the abuse claim that was central to that lawsuit had been ruled to be substantiated by DCS.

“We’re still in business, so you can draw your own conclusions as to the merits of that suit,” Smith told legislators.

Lawmakers were poised to add a version of the immunity proposal to an unrelated bill during the final days of the legislative session in April.

Then an IndyStar story detailed sexual abuse allegations at Pierceton Woods. Quickly, lawmakers removed the language.

Update, Nov. 29, 2023: This story has been updated to include the name of the psychologist who reviewed allegations against Pierceton Woods Academy on behalf of a family suing the facility.