No other state spends less on school infrastructure per student than Idaho. As a result, many students, especially those in rural districts, deal with leaking ceilings, freezing classrooms and discolored drinking water. Some students have to miss school when the power or heat goes out.

School districts often can’t build or repair buildings because Idaho is one of only two states that require two-thirds of voters to approve a bond. Some districts have held bond elections several times only to see them fail despite having support from a majority of voters. But the Legislature has been reluctant to make significant investments in facilities. Administrators say they don’t know how they’ll keep their schools running and worry that public officials don’t understand how bad the problems are.

We heard from community members in 108 of Idaho's 115 school districts.

Boise

Idaho hasn’t done an official assessment of school building conditions in 30 years. The Idaho Statesman and ProPublica tried to fill this gap with the help of people who know the system best. We surveyed all 115 public school district superintendents, and 91% responded. Every superintendent who responded said they have at least one facilities problem that poses a significant challenge, and 78% told us they have five or more. Then, we went to communities across the state. Thirty-nine schools took us on tours, often led by district maintenance directors. We also collected stories and photographs from 233 students, parents, educators and others, who described how the conditions affect their lives.

Read more about our survey and outreach efforts.

“Communities show what is valuable by what we build,” said David Reinhart, West Ada School District’s chief operations officer. “When our students are in old and run-down buildings, it signals to them that what they do in school is of little value.”

“It makes school less enjoyable, harder to focus,” said Luke Sharon, a senior at Lake City High School in Coeur d’Alene.

“The kids see it,” said Amy Eslinger, who graduated from Emmett High School in 2009. “I grew up knowing how bonds and levies worked but never saw them pass and watched myself and my peers suffer from it.”

Here’s what students and educators across the state told us about the floods and leaks, overcrowding and inaccessibility, safety and outages, crumbling buildings and heating and cooling problems that impact every part of their day.

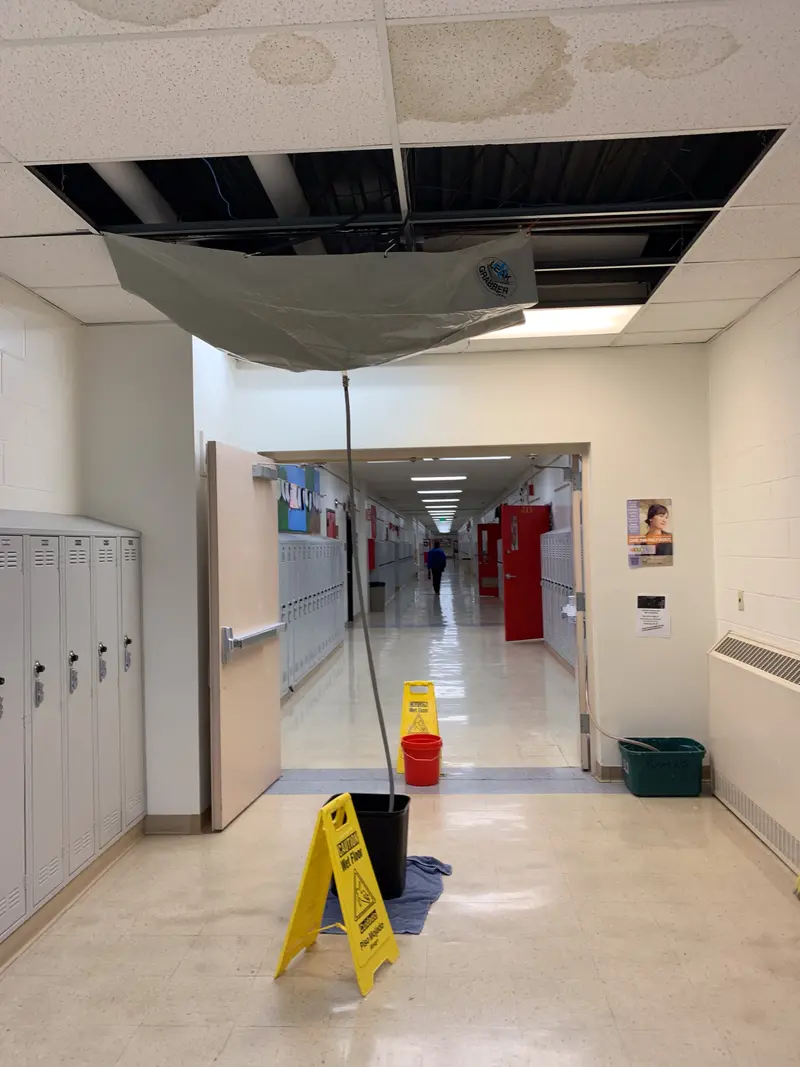

Floods and Leaks

Discolored Water, Falling Ceiling Tiles, Ruined Projects

50% of Idaho superintendents we heard from said leaks pose a significant challenge or require major repairs, while 61% said they had problems with their roofs and 58% said the same about bathrooms.

“The leak made us feel like there was yet another way our school is falling apart. We were also sad because something like this could damage our precious instruments that we most certainly could not replace for a long time due to cost.”

Laura Woras, music teacher

Idaho City Middle/High School, Basin School District

Laura Woras’ music classroom has flooded two years in a row.

Woras went to drop off supplies in her Idaho City classroom during spring break in 2022 and found the area around her desk flooded and hot water shooting out of a wall. It destroyed the floor pillows she had bought for students to sit on while playing their instruments. The next year, it happened again. The superintendent told us the old pipes spring leaks once a month and need replacement.

Separately, the school struggles with leaks from its fire sprinkler system. A levy that would have fixed this failed to pass in November.

“Something is always falling apart in our school district.”

Natalie Kulick, science teacher

Idaho City Middle/High School, Basin School District

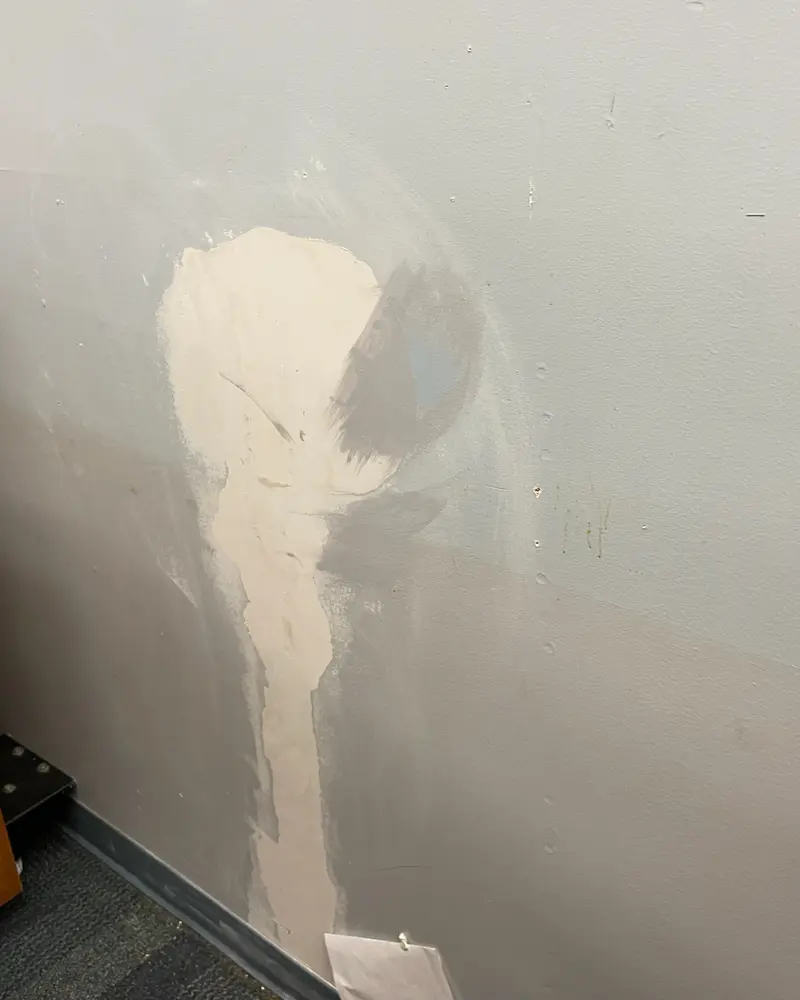

In Kulick’s class, multiple leaks have sent water pouring down the walls, destroying cards from former students, workbooks, papers and posters.

“The previously leaking roof hadn’t been addressed due to budgetary constraints. Due to the heavy snow and already bad roof, it caused the ceiling to collapse. We’re hoping the repairs will hold until we can figure something else out about replacing the whole roof.”

Jason Moss, superintendent

Grace Joint School District

“At Post Falls Middle School, class would be moved to a different room temporarily because a tile from the ceiling had collapsed due to water damage. Sometimes we would carry on anyway and ignore it.”

Grey Goodwin, 2023 Post Falls High School graduate

Post Falls School District

The district said it has since repaired sections of the roof.

The land that the Basin School District’s schools sit on used to be a pond that had been dredged by miners. During spring runoff, the elementary school floods.

Spring runoff goes under the building, creating a musty smell. “My first year here I thought it was a dead mouse.”

Jill Diamond, principal

Potlatch Elementary School, Potlatch School District

“There’s a room that you can’t even go in on a rainy day, because it just smells terrible.”

Michelle Tripp, principal

Ross Elementary School, Kuna School District

“The water is loaded with iron and tastes terrible.” 1 “Old buildings with lead in pipes.” 2 “Concerns with drinking water have caused us to get water delivered. … Some of the water is colored in some of the classroom sinks.” 3

1 Scott Davis, Kootenai superintendent. (The district scraped together grants and donations to add a filtered bottle fill station to each building.)

2 Mark Kress, Snake River superintendent. (The district said it has mitigated lead levels in drinking water and tests the water monthly.)

3 Allen Mayo, Shoshone-Bannock administrator

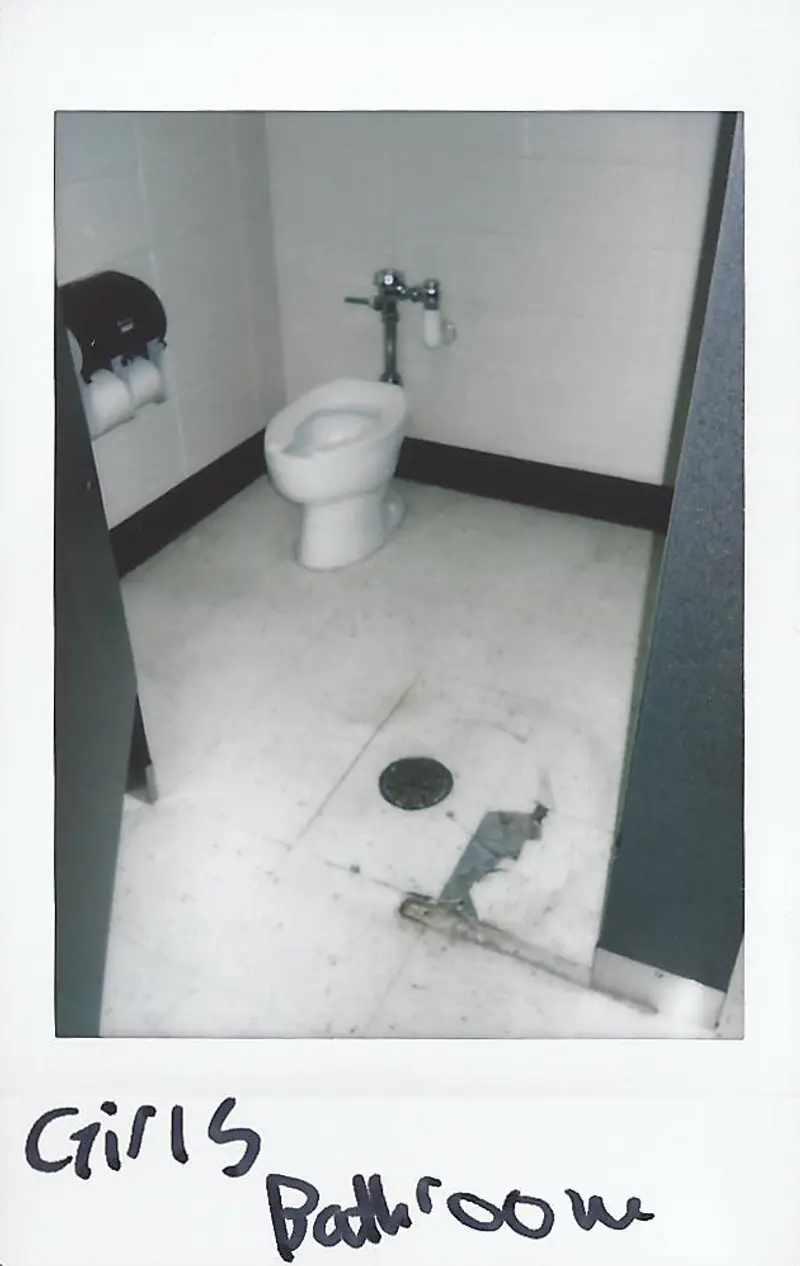

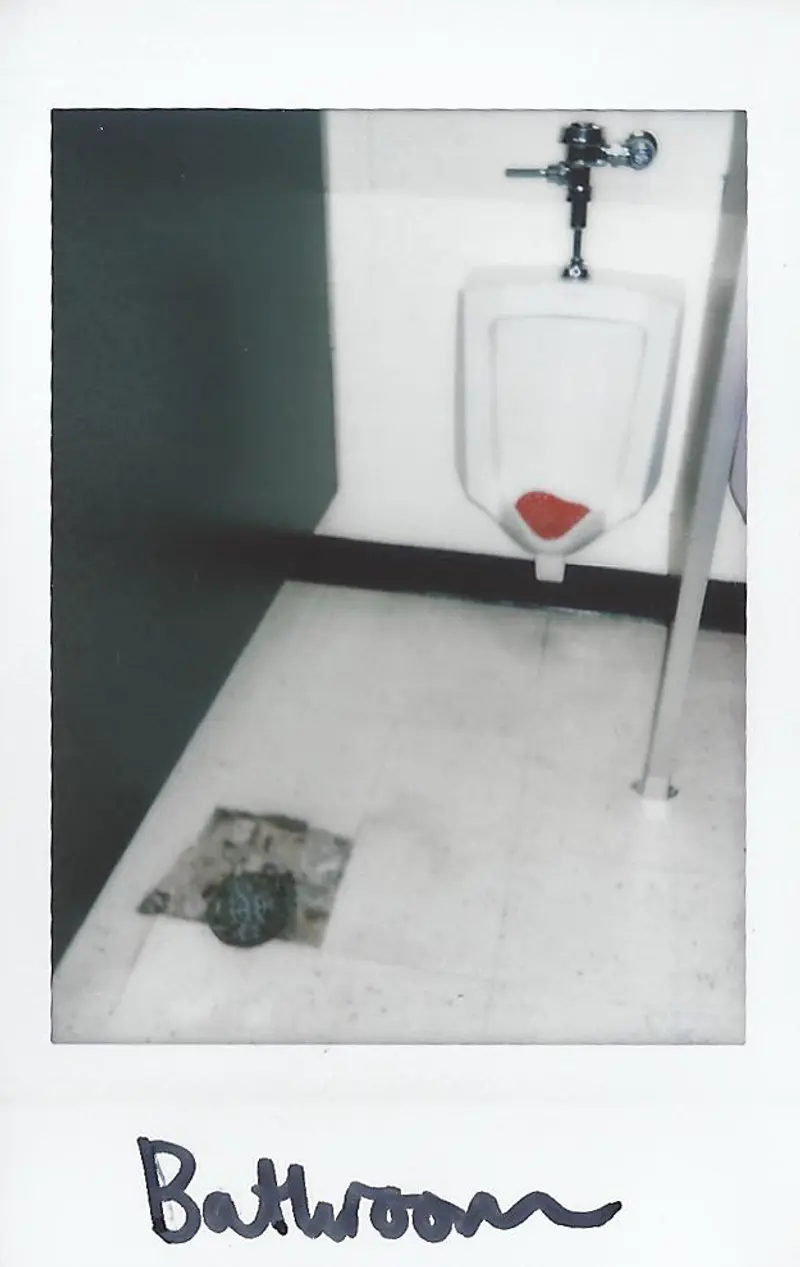

Bathroom drains at Canyon Springs High School, an alternative school in the Caldwell School District, are “popping up out of the ground” because of old rusty piping that has shifted, said Bernie Carreira, the district’s maintenance director.

“We have had to bring in port-a-potty restrooms when plumbing systems have failed.”

Matt Diel, facilities director

Lake Pend Oreille School District

Overcrowding and inaccessibility

Classes in Stairwells and Closets

28% of superintendents we heard from said overcrowding or use of portable buildings is a significant challenge. 58% said accessibility for people with disabilities poses a significant challenge or requires major repairs.

“The first two or three minutes of passing, it’s sardines.”

Tracy Donaldson, vice principal

Kuna High School, Kuna School District

Donaldson described the crowded hallways. The high school was designed for about 1,400 students, but it serves about 1,900, according to the district.

“Our biggest concern is lack of space. We are using 18 modular classrooms at Rigby High School.”

Chad Martin, superintendent

Jefferson County School District

The district has been relying on portable buildings because there is a shortage of space.

“Underclassmen without cars are forced to eat on the floor in the halls due to the lack of space in the cafeteria.”

Claire Yoo, 2023 alum

Idaho Falls High School, Idaho Falls School District

The school was built for 900 students but serves about 1,250, according to the district. The cafeteria accommodates about 200 students.

Moscow High School has 814 students but only room for about 100 in the cafeteria.

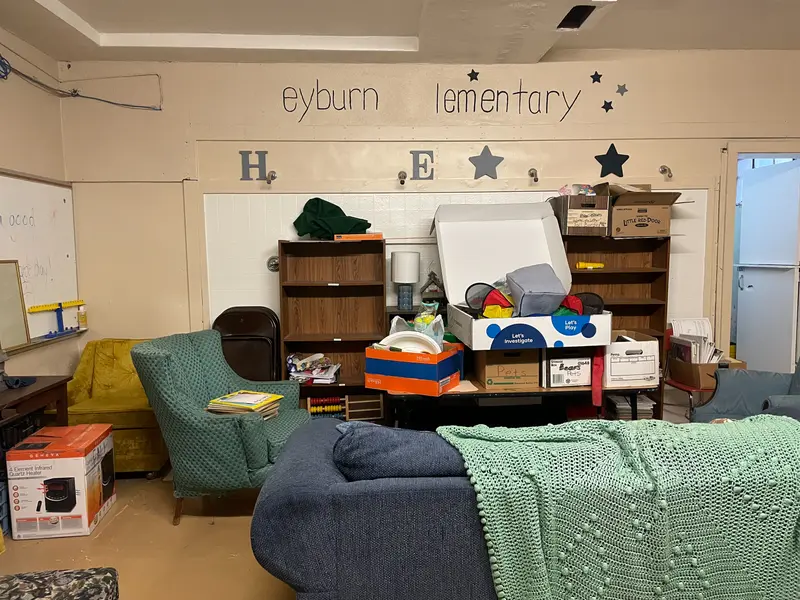

At Heyburn Elementary in the St. Maries School District, a stairwell at the front entrance was turned into the music classroom.

Photo class is held in a former storage room in the Plummer-Worley School District.

“Most high school PE classes are not able to use the gym most of the time since it’s too small. … Not enough fields were built on campus for the number of students we have now.”

Natasha Gartstein, ninth grade student

Moscow High School, Moscow School District

As a result, the district has to transport students to nearby parks and the University of Idaho for physical education, cutting into class time. On one busy week in the fall, the district had 28 bus trips from the school.

At Heyburn, a teacher’s lounge is in an old locker room, where showerheads are still attached to the wall.

About half of superintendents said they have buildings that aren’t compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act.

Schools built before the act have some flexibility in meeting the requirements.

“He can't ever really just be free to explore because he could tip over the edge. … I think there's a lot of learning that kids get when they can freely explore their world. My little guy doesn't get that.”

Marisa Smith, mother of a second grade student

Discovery Elementary School, West Ada School District

Marisa Smith’s son, Tug, uses a wheelchair and is legally blind. He can’t access the playground unless teachers carry him because it has wood chips and a steep drop from the curb. After reporters reached out, the district said it would make some improvements. But the playground would still have wood chips, which are difficult to navigate in a wheelchair.

“We typically have to move students with physical disabilities out of their neighborhood school to a newer school that can better accommodate their physical needs.”

Wendy Johnson, superintendent

Kuna School District

“It’s kind of just really embarrassing. … I oftentimes would fall out of my wheelchair and hurt my knees again.”

Ammon Tingey, 2023 alum

Highland High School, Pocatello-Chubbuck School District

Ammon Tingey described climbing up and down stairs every day to get to honors classes while he was supposed to be using a wheelchair after an injury. He said he was discouraged from taking the classes because they were on the bottom floor and the school didn’t have an elevator. The district did not list accessibility as an issue in its survey. It said it offers more than one section of honors courses, and there would have been another option for students to access on the main floor. The school also has a wheelchair lift in one section of the building.

Safety and Outages

Fire Risks, Power Outages, Security Flaws

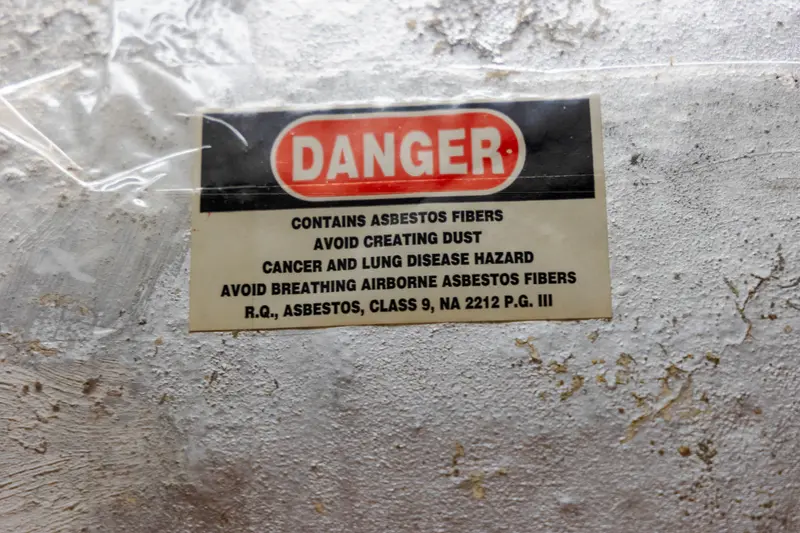

58% of Idaho superintendents we heard from said security poses a significant challenge. 31% said asbestos does and 26% said fire and emergency preparedness do.

“My heart was racing because I’ve heard in the news of things like this happening. … It’s just hard to think what if this would have been real and there actually was someone there and they made a mistake like this. We were like sitting ducks.”

Bryn Bowersox, 10th grade student

Moscow High School, Moscow School District

Bryn Bowersox, 10th grade student

Moscow High School, Moscow School District

Bryn Bowersox was in PE class earlier this year when the school went into lockdown because of a shooting threat. The announcement couldn’t be heard in the gym, and the door didn’t lock securely, according to the district. Bowersox said the class learned of the threat late when a teacher received a message on his phone. The district has since installed new announcement systems and purchased new locks.

Superintendents across the state were able to make some security upgrades with a state grant created this year that provided each school with up to $20,000, but many said it wasn’t enough to fully secure their older schools.

“Not all students can hear the public announcements, and not all classroom teachers can easily communicate with the office.”

Superintendent*

“We have no secure entries and high concerns for many ‘what if’ security scenarios.”

Superintendent,*

referring to the main entrances

*We are not naming the superintendents or their districts to avoid exposing security concerns.

A fire broke out at Highland High School in the Pocatello-Chubbuck School District earlier this year and destroyed the cafeteria, gym and band rooms.

The building had previously failed a fire inspection, but the district said that the alarm system was still operational. During the fire, the school’s sprinklers went off, but the alarm didn’t activate. The district said it has since serviced alarms at all of its schools. The damage will be covered by insurance, but the district ran a bond election in November hoping to expand and upgrade the school while rebuilding. The bond measure failed, despite garnering 56% of votes.

“The elementary has no fire suppression system.” 1 “Don’t have a sprinkler system for fires.” 2 “Does not have a functioning fire control system.” 3

1 Brian Hunicke, Basin superintendent

2 Scott Davis, Kootenai superintendent, about two of the district’s three schools

3 David Sotutu, superintendent of New Plymouth School District until June, about the sprinklers in the district’s career technical education building

“The middle school is loaded with asbestos.”

Scott Davis, superintendent

Kootenai School District

The asbestos is not exposed but makes what would otherwise be simple repairs and upgrades challenging and expensive, Davis said.

“A student plugged their laptop into one of these outlets. There was a pop, a spark.”

Jennie Withers, teacher

Meridian Middle School, West Ada School District

“The kids know it will flicker once, and then they’re waiting. They’re like, ‘OK,’ and it’ll flicker twice, and then they’re like, ‘OK, three times.’ … If it hits the third time, then it’s going to be out for a while — and they know that.”

Brian Hunicke, superintendent

Basin School District

Hunicke said the district had eight power outages last year, and its generator only covers refrigeration, the computer server and emergency lights.

Some districts have also had challenges making Wi-Fi work in their older buildings.

“Some days the Wi-Fi will just stop working. This means that some teachers who rely on PowerPoints or internet access can’t continue with what they had planned for that day.”

Reesa Loewen, senior

Kamiah High School, Kamiah School District

Jill Patton, principal of Pioneer Elementary School in the Salmon School District, said students have been kicked off the internet in the middle of state exams because of the building’s poor Wi-Fi.

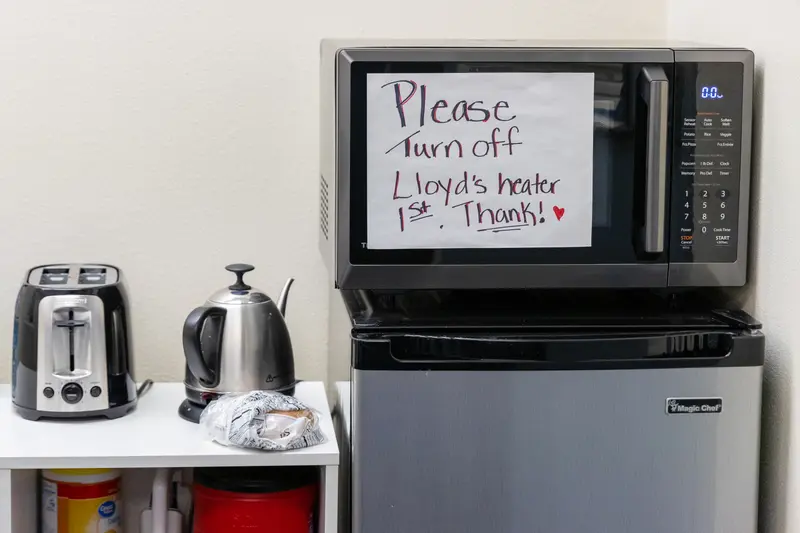

At Caldwell’s Syringa Middle School, the breaker trips if a heater and the microwave are turned on at the same time.

Crumbling Buildings

Deteriorating Foundations and Falling Bricks

41% of Idaho superintendents we heard from said structural issues like cracks in the walls or foundation pose a significant challenge or require major repairs.

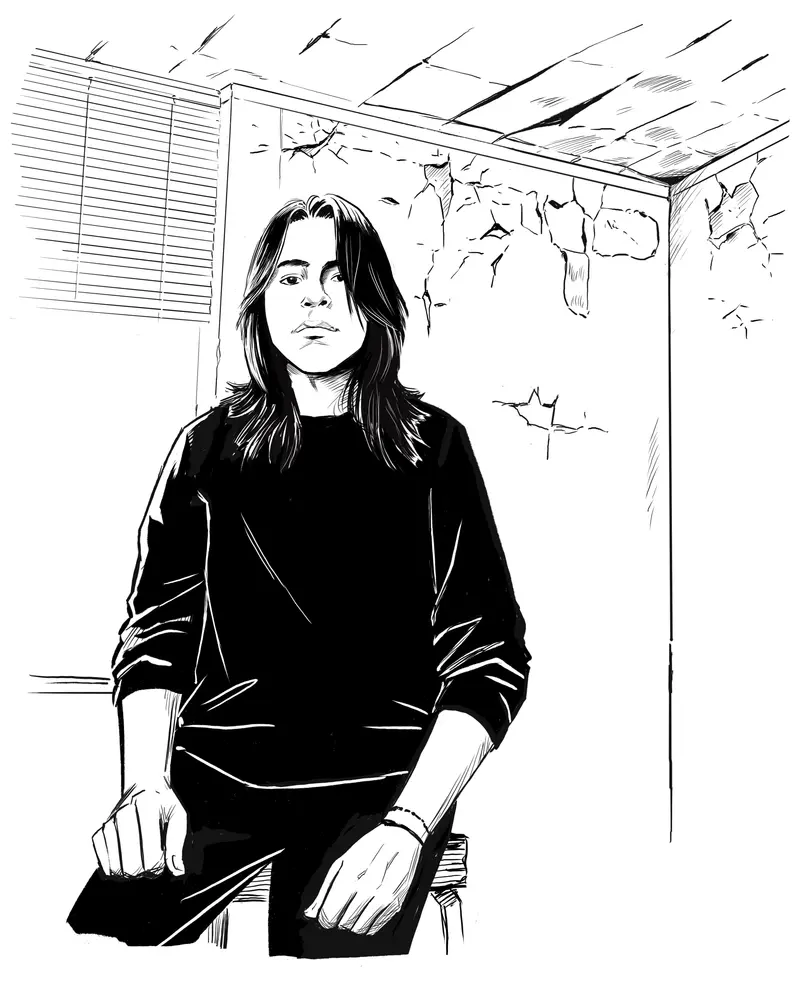

“The look of the school is kind of deteriorating. … Just walking in and seeing something that looks like this is almost depressing.”

Diego Hernandez, 10th grade student

Canyon Springs High School, Caldwell School District

Caldwell Superintendent N. Shalene French said all 10 of her district’s schools are in poor condition. At Canyon Springs, an alternative school that students describe as deteriorating, about 80% of students are people of color, and more than 96% come from low-income households.

“The foundation is crumbling. … You keep up with what you can; you can’t fix a crumbling foundation.” 1 “Foundation and wall cracks are worrisome.” 2 “We know there is probably a crack in the foundation; however, with no money to fix it, we are left to just simply prepare for heavy rains as much as possible and to devote extra time to clean up efforts.” 3

1 Troy Easterday, superintendent at Salmon School District

2 Joe Steele, superintendent at Butte County School District

3 Megan Sindt, superintendent at Avery School District

“The state of our buildings, particularly the outer buildings, is embarrassing. … School should be a place of security and a place to be proud of.”

Jennie Withers, teacher

Meridian Middle School, West Ada School District

“Holes in the walls, leaks, exposed wires — they are distracting.”

Leila Guffey, senior

Kamiah High School, Kamiah School District

At Kamiah High School in the Kamiah School District and other schools we visited, students told us that their schools’ appearance affected how they viewed their schools and themselves.

Bricks have cracked and pieces have fallen out at Jefferson Middle School in the Caldwell School District.

They haven’t hit anyone, but it’s a potential hazard, said Bernie Carreira, the Caldwell maintenance director.

Schools also have structural issues with windows, which were listed as a problem by 55% of superintendents we heard from.

In three districts, teachers or superintendents reported that windows have fallen out. In another, the deteriorated windows allow bats to make their way into the high school two to three times each fall.

“Bats come in through the window casings. … We keep the ‘bat net’ handy at all times.”

Janet Williamson, superintendent

Camas County School District

Heating and Cooling Problems

Blankets, Coal Boilers and Poor Ventilation

68% of Idaho superintendents we heard from said heating poses a significant challenge or requires major repairs. 67% said the same for cooling.

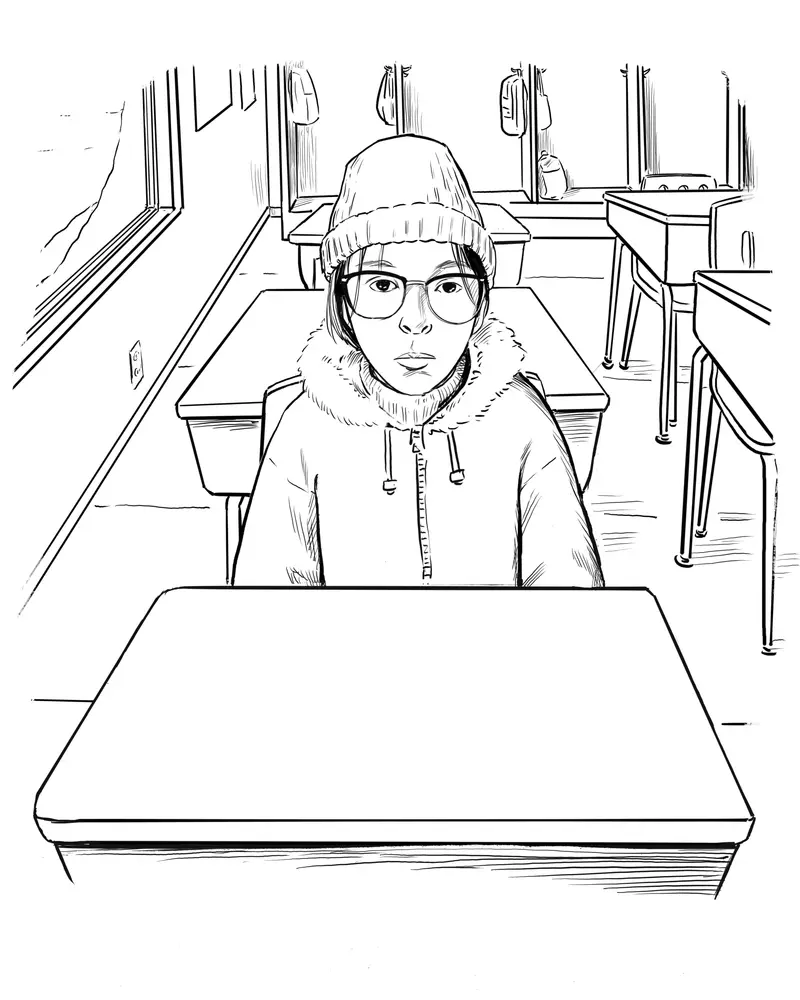

“It’s extremely hard to focus on schoolwork while shivering.”

Kendall Edwards, ninth grade student

Moscow High School, Moscow School District

Edwards said some rooms are freezing in the winter. Frank Petrie, Moscow’s maintenance director, said heating is a challenge because of antiquated systems.

“Even as a kid in elementary school, I knew that it probably wasn’t normal to have to wear coats inside occasionally.”

Ali Johnson, 2021 alum

Capital High School, Boise School District

“I know one teacher who keeps a stack of blankets in his room so kids can cover up while he teaches.”

Cyndi Faircloth, teacher

Moscow Middle School, Moscow School District

Brian Hunicke, superintendent at Basin School District, told us that at Idaho City Middle/High School, the heat didn’t work about 10 times last year, not including during power outages. When it happens, students “suffer for about a day” before the district can get someone in to fix it.

“The district is still using coal to heat buildings. The coal creates dirty air outside the buildings, and depending on wind direction it can unintentionally compromise indoor air quality. As we have looked for ways to improve air quality, we recognize that dirty air can impact those with compromised immunity and asthma.”

Shane Williams, superintendent

West Jefferson School District

Coal boilers have become increasingly rare in schools and homes across the country over the past few decades.

Russell Elementary School in the Moscow School District has a boiler from when the school opened in 1926. If it were to break down, it would be hard to find replacement parts, the district said.

Heat is also a problem when school starts in the late summer, educators say. It’s “sweltering.” 1 “Over 100 degrees in the fall and late spring” inside. 2 “Melting in the hot conditions.” 3 “It gets so hot in the afternoon that students start to put their head down. … It makes it difficult to teach kids.” 4

1 Janet Avery, Potlatch superintendent

2 Robyn Bonner, head teacher at Peck Elementary in the Orofino School District

3 Erin Heileman, teacher at Morningside Elementary School in the Twin Falls School District

4 Gerald Dalebout, social studies teacher at Moscow High School in the Moscow School District

“There is no ventilation in that school, and it does not meet any EPA standards for fresh air intake or carbon dioxide levels, which were tested by the district.”

Ken Eldore, facilities director until June

Priest River Junior High School, West Bonner School District

Another administrator also told us about the levels, but interim superintendent Joseph Kren, who was hired in October, said he couldn’t find a record of a test.

“Emmett Middle School lacks adequate ventilation, which I believe is a contributing factor to high levels of flu and illness.”

Craig Woods, superintendent

Emmett School District

Emmett High School’s air quality is better than the middle school’s after upgrades, but is still “not up to today’s required air circulation standards,” according to its superintendent.

“The leak made us feel like there was yet another way our school is falling apart. We were also sad because something like this could damage our precious instruments that we most certainly could not replace for a long time due to cost.”

—Laura Woras, music teacher, Idaho City Middle/High School, Basin School District

“The first two or three minutes of passing, it’s sardines.”

—Tracy Donaldson, vice principal, Kuna High School, Kuna School District.

“He can’t ever really just be free to explore because he could tip over the edge. … I think there’s a lot of learning that kids get when they can freely explore their world. My little guy doesn’t get that.”

—Marisa Smith, mother of a second grade student, Discovery Elementary School, West Ada School District

“My heart was racing because I’ve heard in the news of things like this happening. … It’s just hard to think what if this would have been real and there actually was someone there and they made a mistake like this. We were like sitting ducks.”

—Bryn Bowersox, 10th grade student, Moscow High School, Moscow School District

“Some days the Wi-Fi will just stop working. This means that some teachers who rely on PowerPoints or internet access can’t continue with what they had planned for that day.”

—Reesa Loewen, senior, Kamiah High School, Kamiah School District

“The look of the school is kind of deteriorating. … Just walking in and seeing something that looks like this is almost depressing.”

—Diego Hernandez, 10th grade student, Canyon Springs High School, Caldwell School District

“It’s extremely hard to focus on schoolwork while shivering.”

—Kendall Edwards, ninth grade student, Moscow High School, Moscow School District

88% of superintendents we heard from mentioned that funding is preventing them from addressing facilities problems.

Districts have cobbled together funds to make some improvements over the years. Administrators said federal COVID-19 relief dollars allowed them to replace expensive HVAC systems and roofs. But that money is nearly gone.

Many superintendents said they felt hopeless about ever passing a bond to renovate or replace schools, especially since funding other educational needs is already a challenge. Districts also regularly ask voters to approve supplemental levies to cover some salaries and operating costs that go beyond state funding.

“Rural school districts can’t pass bonds to build new facilities,” said Todd Shumway, superintendent of the North Gem School District. “It only takes a few to defeat a bond.”

Not passing a bond means districts not only worry about maintaining their buildings, but also about what would happen if a gas line shuts down, the boiler stops working or the sewage system fails. And it means that as Idaho faces a teacher shortage, qualified educators can look across state borders at modern schools in better-funded districts — and decide to leave the state behind.

What We’re Watching

During Donald Trump’s second presidency, ProPublica will focus on the areas most in need of scrutiny. Here are some of the issues our reporters will be watching — and how to get in touch with them securely.

Learn more about our reporting team. We will continue to share our areas of interest as the news develops.

Sharon Lerner

I cover health and the environment and the agencies that govern them, including the Environmental Protection Agency.

Andy Kroll

I cover justice and the rule of law, including the Justice Department, U.S. attorneys and the courts.

Jesse Coburn

I cover housing and transportation, including the companies working in those fields and the regulators overseeing them.

If you don’t have a specific tip or story in mind, we could still use your help. Sign up to be a member of our federal worker source network to stay in touch.