This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with the Idaho Statesman. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

The Idaho Statesman and ProPublica need your help to report on the conditions of Idaho’s public schools. Please get in touch.

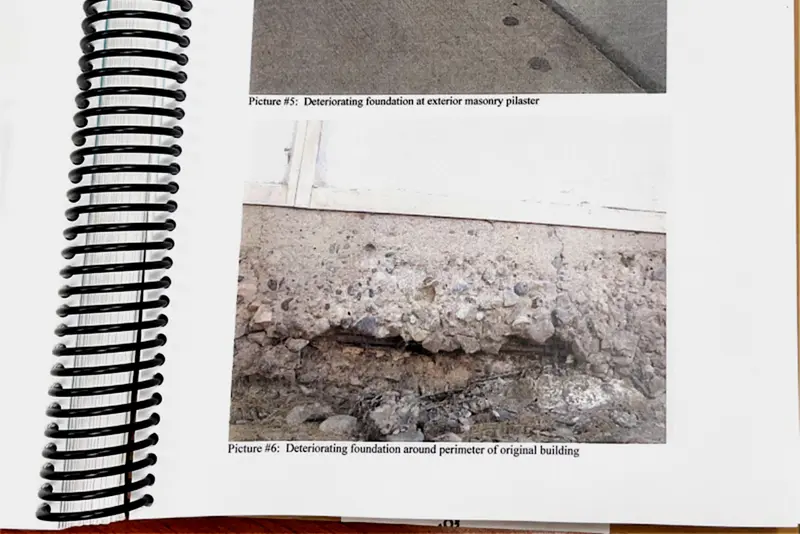

As a member of the school board in the remote Central Idaho town of Salmon, Josh Tolman worried that an earthquake would turn the elementary and middle schools to rubble. The foundations of the schools were crumbling. The floors buckled. The district canceled school whenever a few inches of snow fell for fear the roofs would cave in.

But Tolman and the school district were in a bind: They couldn’t convince enough voters to support a tax increase that would allow the district to build a new facility. The school board ran six bond elections in seven years. But even though 53% of the community supported the bond in one of their first attempts in 2006, it wasn’t enough. Idaho is one of two states that require two-thirds of voters to support a bond for it to pass.

“Unless an existing school actually falls to the ground and becomes unusable, I don’t perceive them ever passing a bond,” Tolman said in a recent interview.

By 2012, the school board and its superintendent had had enough. They decided to turn to a state program that lets school districts borrow money from the state if they have unsafe facilities and can’t pass a bond or figure out another way to fix them. The loan program had been created after the state Supreme Court ruled that Idaho had failed to comply with its constitutional mandate to provide a “safe environment conducive to learning.”

Earlier this year, the Idaho Statesman and ProPublica reported that dozens of school bonds that were supported by a majority of voters had nonetheless failed because of the two-thirds threshold. But, like the bond elections, this state fund also set a high bar and never became a solution to the funding problem schools faced. Since it was created in 2006, the program has been used only twice. And it hasn’t been used in nearly a decade.

Ultimately a state panel decided that Salmon’s problems — though bad enough to pose safety hazards — did not warrant a new school under the law, only new roofs and seismic reinforcements.

The approved funding was only a quarter of the amount the district estimated it would need to build a new K-8 school. And with dwindling enrollment, the school board decided it couldn’t afford to keep both the elementary and middle schools open.

“It was at that point where you’re grasping at straws to try and get something done for the children of this community, and the state basically said, ‘Keep on grasping,’” Tolman said.

The district closed the middle school and added portable buildings — trailers without bathrooms or sinks — to the elementary and high schools.

Today, the abandoned Salmon Middle School sits behind a tall razor-wire fence in a valley said to be the birthplace of Sacagawea, the Shoshone woman famous for her critical work on the Lewis and Clark expedition. The building’s roof is pocked with gaping holes, and insulation hangs down into hallways. Framed accreditation certificates, a crushed globe and pieces of ceiling tiles pepper the ground of eerily quiet classrooms.

The building is now an eyesore, visible from the nearly 70-year-old elementary school next door. Despite the structural repairs to that building, Salmon — where 43% of students are from low-income families — faces many of the same problems that existed when the district went to the state for help, plus some new ones. About 275 elementary students go to school with failing plumbing and uneven floors, where sewage sometimes backs up into a corner of the kitchen. For years, water from the drinking fountains came out brown.

Students who learn in deteriorating facilities have worse educational outcomes than those in newer, more functional schools, national research shows.

“How long are you going to keep kids in subpar classrooms and subpar situations?” said Russ Chinske, who has been a teacher in Salmon for about 20 years. “How long are you going to force the school district to use stuff that’s used up?”

Cori Allen has two kids in the district. Her oldest, now a sophomore in high school, could have been in the first kindergarten class to attend school in the new K-8 building. Instead, he spent years attending school in portable buildings.

The state constitution talks about “equal education,” and Salmon kids “are in facilities that are, in my opinion, totally inappropriate for a child to be learning in,” Allen said. “It’s just not fair that geographically we have to put up with it.”

A Fund Designed to be “Difficult to Use”

The majority of districts in Idaho are smaller, rural communities — including many with vast areas of federal land — and are less able to support tax increases. Some have a growing number of retirees who don’t have kids in school; others have shrinking enrollment because of a decline in logging or other industries. Idaho’s limited resources and restrictive policies have left the state with aging schools and left districts without funding to replace them.

For decades, educators have raised the alarm about the condition of school buildings in Idaho. In the 1990s, a group of superintendents, districts and parents sued the state over inadequate funding. A statewide assessment funded by the Legislature shortly after found that 71 facilities, or about 10% of the buildings used for instruction in the state, were dangerous or had serious problems needing immediate attention. As the case progressed, a district court cited an analysis that found an American Falls school, in southeastern Idaho, would likely collapse in a seismic event, a probable threat for that area. In Troy, an inspection found the high school was unsafe to occupy. But with no funds to fix it, the school remained open for years.

After multiple appeals, the Idaho Supreme Court sided with the education stakeholders in 2005. The justices agreed with a lower court that the state’s “reliance on loans alone to pay for major repairs or the replacement of unsafe school buildings was inadequate for the poorer school districts.” They told the Legislature that lawmakers had a responsibility to make sure school facilities were adequately funded. “The list of safety concerns and difficulties in getting funds for repairs or replacements is distressingly long,” the court said.

The next year, legislators tried to address the ruling. A Republican lawmaker introduced a bill to start the process of lowering the two-thirds requirement that made it so difficult to pass bonds, but legislators never gave it a hearing.

Instead, the Legislature took up a bill that several lawmakers said at the time wouldn’t fully solve the problem. One key element would create a $25 million loan program, the Public School Facilities Cooperative Funding Program, intended to help districts that couldn’t pass bonds to repair or replace their unsafe schools.

The proposed program had a high bar: School districts would qualify only if their buildings presented either an “unreasonable risk of death or serious bodily injury” or an “unreasonable health risk.”

The program’s money would also come with strings attached. If approved, district officials would have to agree to forgo local control throughout the process and give a state-appointed supervisor the power to make decisions for the schools — even the power to dismiss the superintendent. The state would then impose a tax on the local community to repay the loan, a potentially enormous deterrent, since the community had already voted down a bond.

The issue generated weeks of legislative debate. One concern was that the new measure would undermine the state’s long commitment to local control of school districts. Some legislators went further, arguing that the program would give too much power to the state, with one state senator predicting that the public response would be like “the revolution that started as a result of the Boston Tea Party.” Some also argued that taxpayers who supported bonds to rebuild schools in their communities shouldn’t be forced to pay for schools in other areas.

Other legislators and education stakeholders believed the bill didn’t go far enough. Robert Huntley, the attorney who sued the state back in 1990, said the Supreme Court decision was “not just about safety issues,” but the Legislature appeared to be focusing on only that aspect. Justices also ruled that the environment had to be “conducive to learning.” “There is serious underfunding and new money is needed,” Huntley told lawmakers, according to legislative meeting minutes.

Despite the concerns, many legislators agreed that it was a step in the right direction. The resulting compromise bill passed with a large majority in support.

Now-Lt. Gov. Scott Bedke, who sponsored the legislation, acknowledged in a recent interview that it’s ultimately the state’s responsibility to provide safe facilities. But, he said, the program was also intended to be a last resort, and the conditions on the funding were meant to provide oversight for the spending of taxpayer money.

“It was created to be, frankly, difficult to use,” said Mike Rush, the former executive director of the State Board of Education who served on the state panel that assessed program applications, including Salmon’s.

The program’s requirements were “onerous,” said Shawn Keough, a former Republican state senator who sponsored the bill that created the program, and that only two districts have used it shows it wasn’t the tool districts wanted.

“I supported the incremental step forward as a potential solution,” she said. “One of my regrets from my 22 years of service was not being able to fix that problem of school facility funding.”

Salmon Closes a School

Tolman, who served on the Salmon school board from 2008 to 2013, was hopeful when the district applied to the state program in 2012. He’d grown up in Salmon and heard about a time when the elementary school had outdoor hallways, a layout ill-suited to a town where winter temperatures sometimes fall below zero. The district eventually enclosed the hallways, but turning what was designed to be a sidewalk into a hallway contributed to cracks and buckling floors.

Less than three years before Salmon applied for the loan, the state agreed to build an entirely new school for the Plummer-Worley School District in North Idaho, where inspection reports had found major structural issues, and the panel determined that the most economical solution was to replace the school. Tolman hoped for a similar outcome in Salmon’s case.

In assessing both districts’ applications, the state panel — which included top officials from the State Board of Education and the divisions of building safety and public works — focused heavily on the funding program’s limitations. According to meeting minutes, panel members said that the remedy had to focus on Salmon’s “safety problem, not the educational environment or the adequacy of the facilities for education.”

They also discussed the law’s language that allowed intervention only in the face of “unreasonable” risks. The term “unreasonable” was not defined in state law, so the panel had to consider what an “unreasonable risk of death” was. Salmon sits in a seismically active area. In 1983, an earthquake killed two children on their way to school in Central Idaho, and in 2020, a 6.5-magnitude earthquake cracked the courthouse in the next county over and spurred avalanches in the Sawtooth mountains. Was the earthquake risk unreasonable?

The panel also struggled with whether repairs alone would be enough to make the schools last another 20 years, which the law also required.

Rush, who voted in favor of repairing the schools in Salmon, said patching up a safety hazard is almost never the best solution. But that was as much as Rush said the panel could offer while still abiding by the law. “By the time the facility gets to the point where it needs to come to this process, they need a new facility,” he said.

Rush said he felt like the program was designed to use the potential for a state takeover to pressure the local community to pass a bond on its own.

In a 2013 bond election, the district had estimated a new K-8 school would cost taxpayers over $14 million. Instead, the panel in 2013 approved $3.6 million to renovate the elementary and middle schools.

Faced with a constrained budget, the district shuttered the middle school. That would leave taxpayers on the hook to repay the state only about $1.7 million for repairing the elementary school and bringing in portable buildings to accommodate middle school students.

The years of debate over how to handle the school conditions created turmoil and sowed distrust in the community, with lots of blame to go around. For some parents, it felt like throwing money at a school that couldn’t be fixed.

“We got a new roof on a turd over there,” said Allen, a Salmon parent. She said it also wouldn’t have gone over well if the state had charged taxpayers for a new school they didn’t vote for. “They could have offered us some resources or some education or opportunities or some sort of a lifeline,” she added. “But they just didn’t.”

While Rush sees value in the program to abate unsafe situations, he said it’s not the ideal solution for aging and deteriorating schools like the one in Salmon.

“For those of us in the educational environment, we wouldn’t say that’s the kind of facility we’d want to send our kids to for the next 20 years,” Rush said. “Granted, they might not die while they’re going to school. But that’s not the only criteria one might want to have for your kids.”

“Our Children Deserve More”

For parents, teachers and staff in Salmon, the conditions of the schools remain a regular frustration a decade after the repairs.

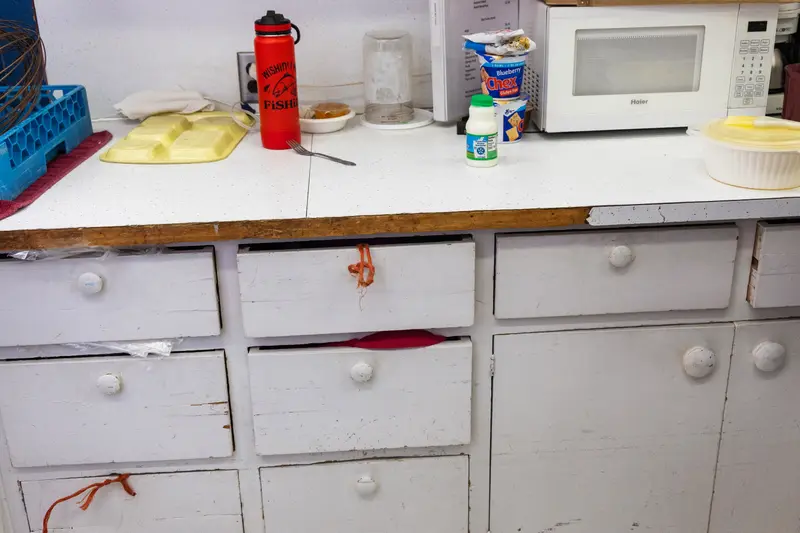

Becky Harbaugh, the head cook at Salmon’s Pioneer Elementary School, has made do with ovens that don’t cook evenly and kitchen drawers and cabinets without handles that she opens with pieces of string. In the winter, her hands have stuck to door handles in subzero temperatures as she gets food from outside storage rooms. The district hasn’t renovated the kitchen, in part because the cost to bring it into compliance with the Americans with Disabilities Act would be too high, Superintendent Troy Easterday said.

What really worries Harbaugh, though, is the narrow hallway and staircase that students have to navigate while carrying their trays of food from the kitchen down into the cafeteria.

“It’s just scary sometimes. I mean, I worry about those kids. Hot soup day, you ought to see me,” she said, holding her breath and staring, motionless, in anticipation of disaster.

Students who use wheelchairs face a different problem. They can’t even line up to get their meals; there’s no ramp.

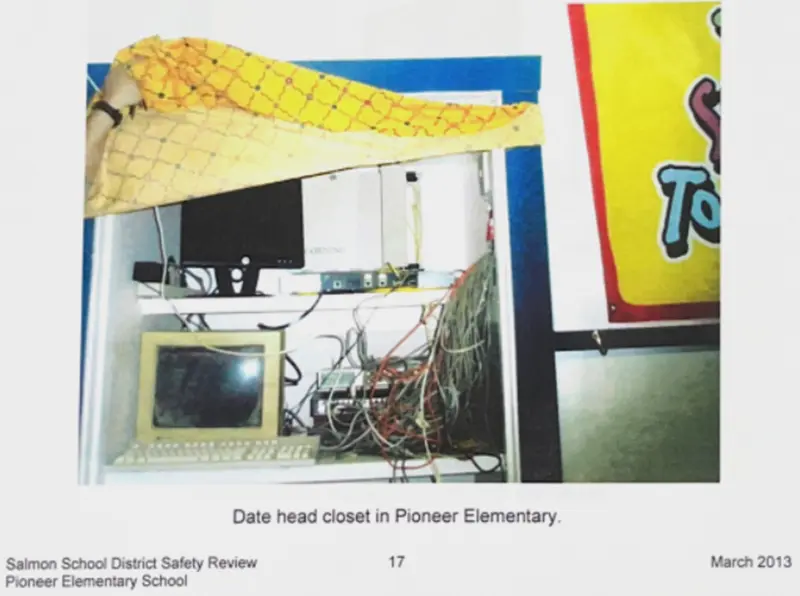

Many of the school’s problems today look nearly identical to those featured in the district’s structural evaluations and engineering reports dating back nearly two decades.

Rebar still sticks out of the crumbling foundation on the side of the building, just as it did more than a decade ago. The internet closet — a stack of shelves in the middle of the hallway — has the same tangle of dozens of wires it did long before students regularly used laptops or tablets in their classrooms. The uneven floors, buckled by what administrators believe are frost heaves from when water freezes or thaws in the foundation, pose tripping hazards — just as they did in 2012. The only difference is the school has put down new carpet.

“It’s just a money pit,” said Bobby Lewis, the maintenance director for the district. When he needs to fix a plumbing problem, he’ll sometimes have to crawl through a 3-square-foot tunnel and chisel out part of the concrete foundation to replace a section of the pipe that’s broken. At some point, that won’t be an option anymore, he said, because it would become unsafe to keep cutting out the foundation.

To deal with the brown water, students carried water bottles throughout the day. Shortly after the state stepped in, the district saved enough to replace its water lines. Over the years, district officials also made one of the bathrooms accessible for staff members with disabilities.

The district invested in its schools to make them as functional as possible, but nothing they did could fix the underlying issues.

“I know we lose people. When they move into town, they’re like, ‘Yeah, I’m not gonna send my kids to school in a facility like this and next to something — razor-wire-topped fence, looks like an old prison,’” Easterday said. “Our buildings scare people off.”

In 2019, the district tried again to pass a bond. It conducted an analysis that showed that despite the state-mandated repairs, the internal issues in the elementary school would be too costly to renovate and would not address the overcrowding, according to documents on the bond effort. The most cost-effective move, the board decided, would be to build a new school.

The district ran a $25 million bond to build a K-8 school — about $10 million more than it had asked for in its previous bond effort in 2013.

The board held meetings and shared information online. But it was still hard to reach the bond threshold. A growing portion of Salmon residents are retired and no longer have kids in school. Some in the community said that if the schools had been good enough for them, they were good enough for current students; others didn’t want higher taxes or felt excluded from the bond process. The district also faced a last-minute push from the Idaho Freedom Foundation, a conservative group that opposes public schools, which it has accused of “indoctrinating students with leftist nonsense.” Disagreements broke out on social media between supporters and opponents.

When the election came around, the bond received the most support that a measure in Salmon had gotten in decades. More than 58% of voters said the district needed a new school and they were willing to pay for it. But once again, it wasn’t enough.

“Our children deserve more than we’re giving them,” said Nancy Fred, who had three sons in the schools, the youngest of whom graduated in 2014.

This summer, a group of parents and community members again held meetings to try to figure out a solution for their schools. Hundreds attended. One parent wrote if they’d had kids before moving to Salmon, they wouldn’t have come, according to documents compiling the feedback from the meetings. Others said the aging buildings make it hard to recruit teachers and professionals to Salmon and that Pioneer Elementary is falling apart “everywhere you look.”

During a tour in May, Jill Patton, Pioneer’s principal, praised teachers for all they have been able to do with what they have. But with a new building, she said, they could do so much more.

“You look at this building, and you can see such heart and such love for kids and such great learning taking place,” Patton said. “And I think, ‘Wow, what it could be if the barriers of the building weren’t there.’”

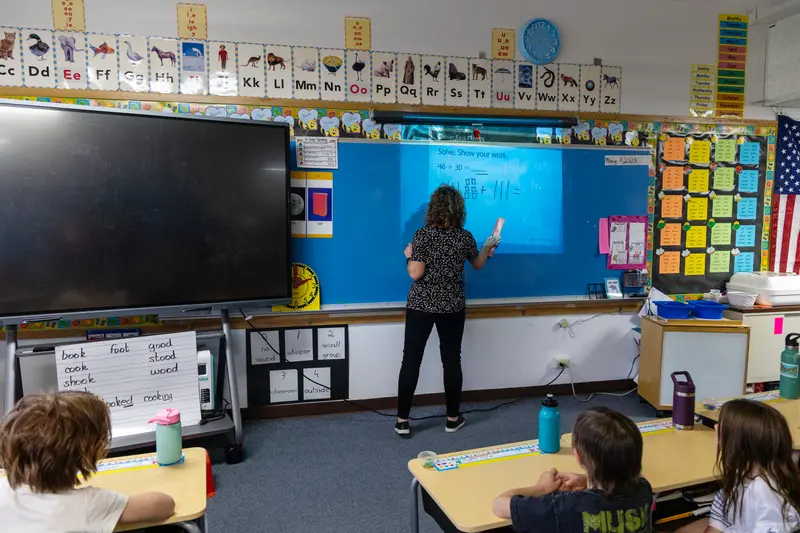

On the day of the tour, the students in Betsi LaMoure’s first grade class had been working on some addition problems. She was trying out a smartboard that a vendor had lent to Salmon in hopes that the district would buy them. But the WiFi wasn’t strong enough to get it working. Connectivity is poor in the area, and retrofitting such an old building is difficult. After multiple attempts, LaMoure gave up. She pivoted to a much older technology, writing on a piece of paper and using a projector to display it on the chalkboard.