An alleged serial rapist was arrested last month with help from evidence saved by a Baltimore County doctor nearly half a century ago. ProPublica highlighted this rare trove of hospital microscope slides in its Cold Justice series and inspired a new Maryland law to protect the evidence.

In this case, the evidence was collected from five women who visited the Greater Baltimore Medical Center for rape exams between 1978 and 1986. All said a man had violated them after breaking into their first-floor apartments in complexes within the same mile radius. Police at the time had not yet started saving standardized rape kits. But a prescient doctor, Rudiger Breitenecker, anticipated that one day, science might advance enough to make use of the specimens.

Most of the evidence collected by Breitenecker between 1975 and 1997 sat untouched for decades, until a new generation of cops recognized its value and slowly began to test it. By 2022, Baltimore County police knew four of the cases shared the same perpetrator’s DNA. (Initial testing didn’t yield a profile from the fifth, according to prosecutors.) But the suspect’s identity was still a mystery.

Enter Detective M. Lane, one of two detectives in the relatively new Special Victims Unit cold case division, who decided to read all of the police reports connected to those slides and link them to other cases. (Lane uses only her first initial on court documents.) She found a reported attack that wasn’t one of the four DNA-linked cases, but which happened just a short walk away from a rape connected to DNA evidence, and just two months later.

The report contained an almost unbelievable lead: A woman attacked on Dec. 3, 1978, told police that the suspect told her his first and middle names: James William. He wore a bracelet with “Jim” on it and said that day was his 26th birthday.

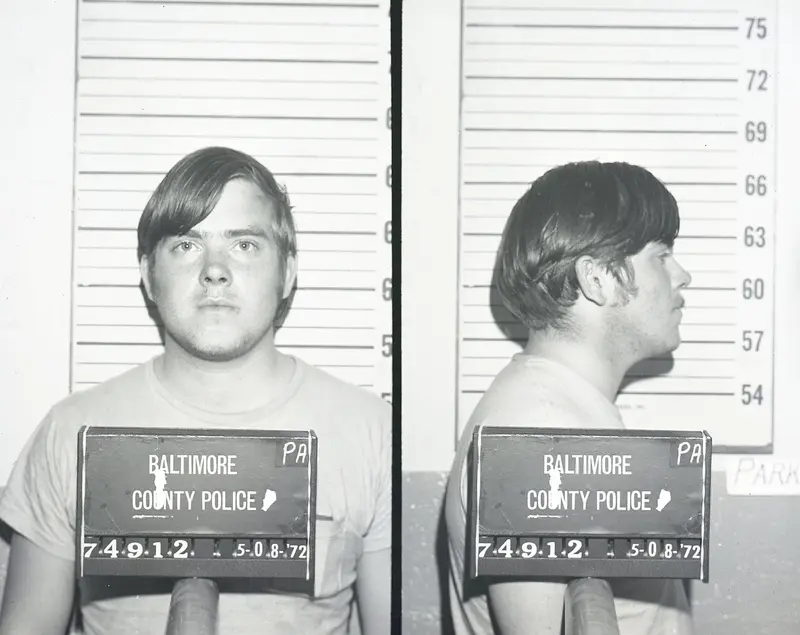

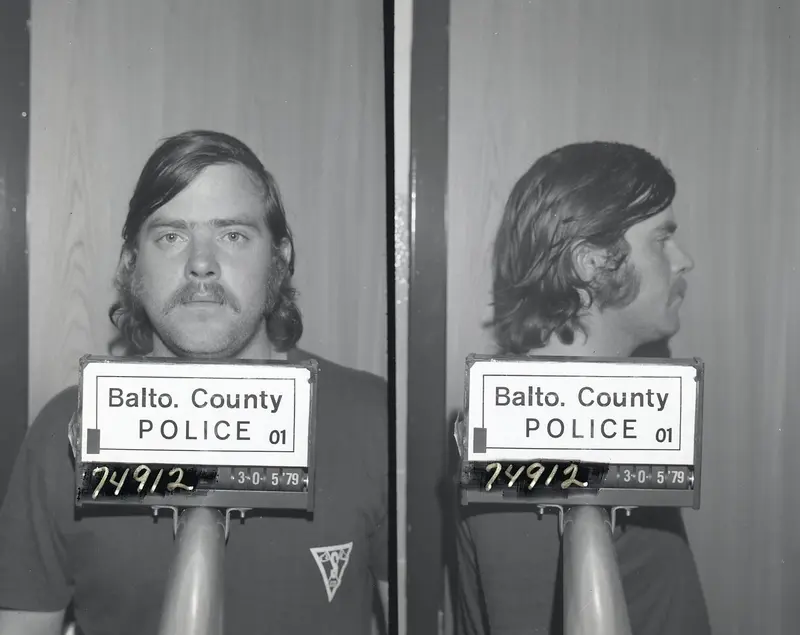

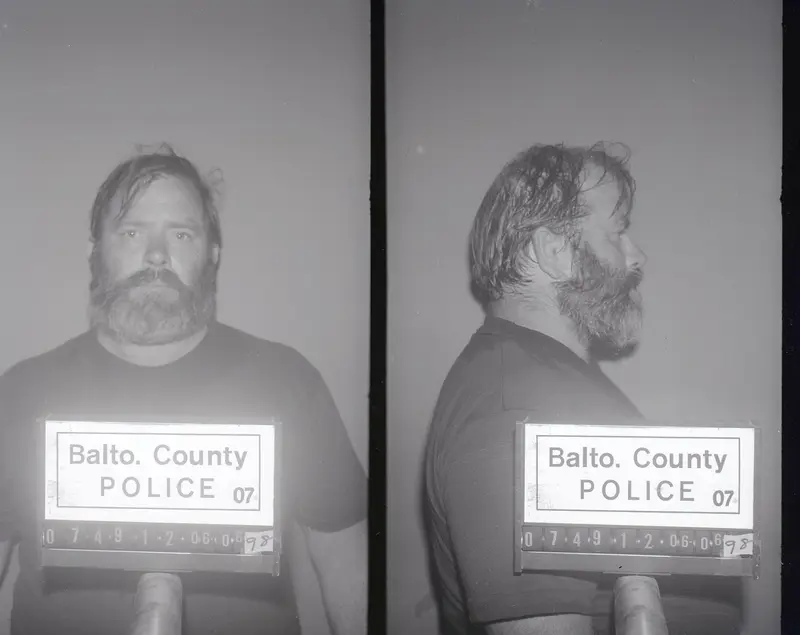

This June, Lane plugged those clues into a police database and found James William Shipe Sr., a man who had been arrested and charged for a separate attempted rape in 1979. Prosecutors at the time had dropped the case; Baltimore County State’s Attorney Scott Shellenberger said it is unclear why. The victim in this later case also reported that her attacker was wearing a bracelet with “Jim” on it.

Lane had Shipe’s fingerprints from that case compared to the one pulled from the 1978 crime scene. They matched. Shipe had arrest reports for charges often associated with rapists: trespass and Peeping Tom, for which he served probation.

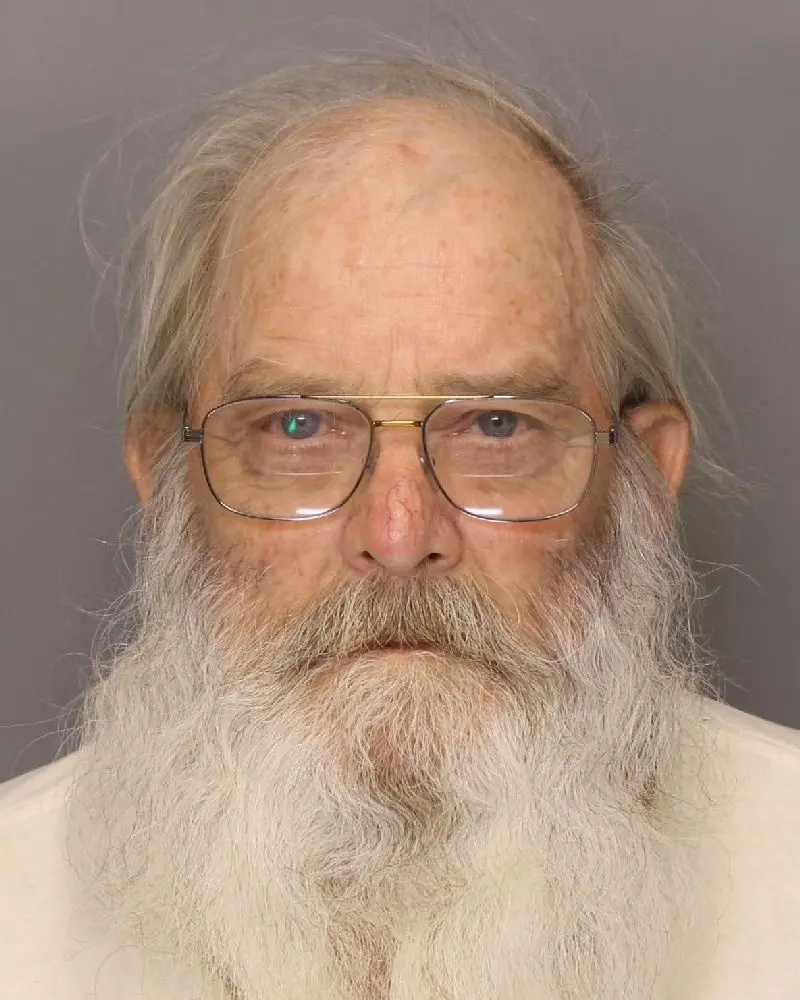

The detective had enough information to request a warrant for Shipe’s DNA. The 70-year-old was living with his wife less than 10 miles away from the scenes of the five attacks.

On July 22, Lane got the results: Shipe’s DNA matched those on the doctor’s rape evidence slides, according to court and police reports. Police had now linked Shipe to five cases by DNA or fingerprints.

Shipe was arrested 10 days later and is now in jail, facing charges in three of the five rape cases; the two other women who were assaulted have since died, and prosecutors are not pursuing charges in those.

ProPublica tried to reach Shipe, who is in a Baltimore County jail awaiting his next court hearing, but could not get through to him by phone. Reached by phone at her home, Cynthia Shipe said her husband has not yet been assigned a public defender.

She said the charges against her husband are “totally bogus” and she believes that he is innocent. She said she did not know about the DNA evidence, but that she’s known him for 37 years and that he’s a “wonderful man” who just sent her a dozen red roses for her birthday and that he “doesn’t have a violent bone in his body.”

Cynthia Shipe said her husband was a trucker until three years ago, when he had to retire due to heart problems, and she worries about his health now. She said he has not been given the proper medication in jail and she’s seen his health deteriorate.

The Maryland Office of the Public Defender said they could not comment on the case at this time.

“I am a new person, I feel totally different,” said Linda Shinault, who reported a rape to police in September 1986. She said someone broke into her apartment, severed her phone cord and was waiting for her in the bathroom after she got out of the shower. She said the attack and not knowing who did it had put a “heaviness” on her. When she got a call from a detective nearly 37 years later telling her a suspect had been arrested, she said she was screaming into the phone, she was so happy. She then told everyone she knew. She considers the doctor’s saving of evidence to be a “miracle.”

“I feel the doctor is looking over us,” she said. Breitenecker passed away in September 2021. Linda said she wanted to tell her story to help other survivors and questioned why law enforcement was waiting “even another week” to test more evidence if there might be more victims whose cases could be solved.

For the Street family, the answer came too late. Dennis Street said his late wife Patricia would have appreciated the answer.

“I'm glad the guy was caught,” Street said. “And I know my wife would be happy, too, after all these years. Thank God for DNA testing. But I don’t know what took so long.”

Patricia Street reported a rape in September 1978 that police say is the earliest case linked to Shipe by DNA so far. She died in 2021 after two decades of health complications.

Baltimore County police say they are continuing to process cold case evidence and investigate whether more cases are tied to Shipe.

Most of the rapists who have been caught with the historic hospital DNA have been found to have a long list of other criminal charges on their records, such as other rapes, theft, burglary and murders. Shipe does not have such charges on his record, according to the Maryland Judiciary online records.

ProPublica helped solve the 1983 murder of Alicia Carter, a 21-year-old college student, by studying perpetrator patterns. Alphonso W. Hill’s DNA has matched 11 hospital slide cases so far, including DNA from the assault of a Goucher student in the same location where Carter’s body was found. After ProPublica’s investigation and police inquiry, he confessed in 2021 to raping and murdering her.

As these cases show, finding suspects who have eluded police for decades often requires more than DNA tests. “You can have all the computers, all the DNA, all these things that you want, but it still takes good old-fashioned police work,” said Shellenberger.

Shipe’s is the first arrest from the new effort to test the hospital slide cases, announced by Baltimore County officials in October 2019. Police have been delayed in part due to a backlog inside their forensics lab.

Like many other agencies, the Baltimore County police face significant staffing shortages. The department has only two dedicated cold case detectives in its Special Victims Unit, though that is more than a previous cold case effort in the first decade of the century, which had no dedicated detectives.

The unit often gets pushed down the priority list for testing even though rape cases notoriously involve serial perpetrators.

As of January 2023, police had about 1,300 hospital slide cases. At the rate of testing so far, it could take another couple of decades to finish processing them.

However, police have made a recent move that should help expedite testing. The remaining evidence, still at the hospital, is moving to police headquarters where it will be logged and sent for testing at a private lab. They are skipping a pre-screening step in their own lab and shipping the slides directly to a private DNA testing company. A police spokesperson wrote to ProPublica that "The Department looks forward to receiving all available evidence and is doing everything possible to expedite the analysis and investigation of these important cases."

Part of that is driven by a new state law passed earlier this year in response to issues raised by ProPublica’s investigation. The law classifies the hospital slides as official rape evidence and requires the police department to count them among its rape kit backlog and retain the slides for at least 75 years after they were collected.

Baltimore County police have released Shipe’s mugshots and are encouraging anyone with information on additional crimes to reach out at 410-307-2020.

Survivors who would prefer to speak with the department’s victim advocate may call 443-345-7587 or email aharkins@turnaroundinc.org.

Survivors can find additional resources at Maryland Coalition Against Sexual Assault and TurnAround, Inc.