This article is co-published with The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan local newsroom that informs and engages with Texans, and with Military Times, an independent news organization reporting on issues important to the U.S. military. Sign up for newsletters from The Texas Tribune and Military Times.

A Texas representative whose district includes one of the nation’s largest Army posts is calling for hearings to examine the military’s pretrial confinement system, which gives commanders the discretion to detain service members facing criminal charges ahead of trial.

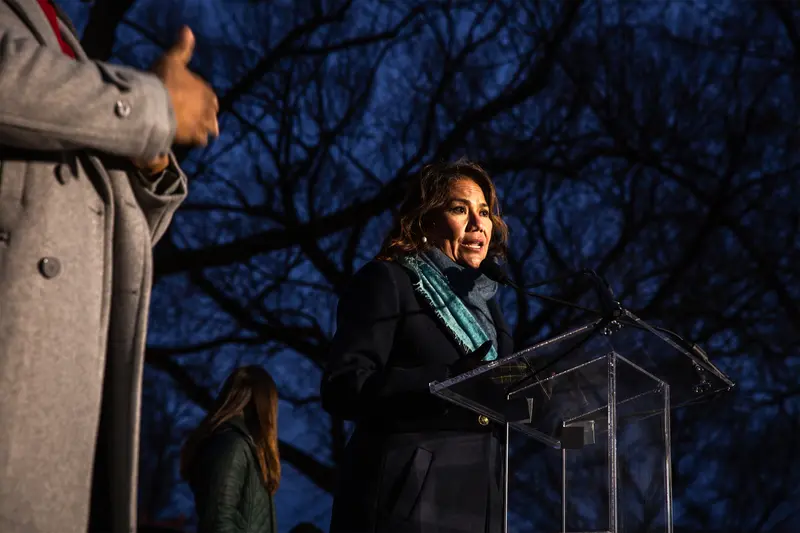

Rep. Veronica Escobar, a Democrat who represents El Paso and sits on the House Armed Services Committee, said this month that an August investigation by ProPublica and The Texas Tribune raises serious questions about the use of pretrial confinement in the military. The news organizations’ first-of-its-kind analysis of nearly 8,400 Army courts-martial cases over the past decade revealed that soldiers accused of sexual assault are less than half as likely to be placed in pretrial confinement than those accused of offenses like drug use and distribution, disobeying an officer or burglary.

“Pretrial confinement had not been on my radar, so it was really eye-opening,” Escobar said of the investigation, which highlighted the case of Christian Alvarado, a private first class who avoided detention for months despite facing sexual assault accusations from multiple women. Alvarado, who has since been convicted of sexually assaulting two of those women, was a soldier at Fort Bliss. Escobar’s district includes the post.

Escobar, who is vice chair of the House Subcommittee on Military Personnel, said that during the congressional hearings she would like to explore ways to ensure all cases across the military are held to the same standard. She also said she reached out to the new commanding general of Fort Bliss to ask more about Alvarado’s case. Fort Bliss officials have declined to discuss with the news organizations why Alvarado was not initially put in pretrial confinement, saying they would not comment on internal deliberations.

The congresswoman has discussed the issue with Rep. Jackie Speier, D-Calif., who chairs the subcommittee. Speier shares Escobar’s concerns and believes pretrial confinement should be “part of the broader work of military justice reform,” her office said. A staffer in Speier’s office said the chair looks forward to learning more from military officials about pretrial confinement at a planned subcommittee hearing on Wednesday that will focus on the implementation of military justice reforms.

Army spokesperson Matt Leonard told Military Times that the rules governing pretrial confinement are “currently under revision.” He declined to provide details, referring questions to the Department of Defense. A DOD spokesperson said the military doesn’t have any “updates to announce at this time.”

News of the proposed revisions comes after publication of the ProPublica-Tribune investigation and of an article by Military Times that detailed another case in which a soldier was not placed in pretrial confinement despite multiple domestic violence allegations. The news organizations are partnering to cover aspects of the military justice system.

Under the current rules that are outlined in the Manual for Courts-Martial, commanders must determine if there’s good reason to believe a service member committed a crime and weigh whether the person is likely to flee before trial or engage in serious criminal misconduct. They must also first consider if less stringent restrictions are enough to keep service members out of trouble. Unlike in the civilian justice system, there is no bail in the military.

Rachel E. VanLandingham, a former Air Force judge advocate, said commanders should not control pretrial confinement because they are not trained as military attorneys. Commanders can override the advice of legal advisers in many situations.

“Because these commanders are F-16 pilots, these commanders are infantry officers, this is not their full-time job,” said VanLandingham, now a professor at Southwestern Law School in Los Angeles.

Congress last year overhauled much of the military justice system, stripping commanders of the power to decide whether or not to prosecute some felony-level crimes, including sexual assault. Amid pushback from military leaders, lawmakers allowed commanders to retain numerous powers, including the ability to place a service member in pretrial confinement.

Escobar had hoped to see broader reforms that would have removed commanders’ prosecutorial authority over all serious crimes, including robbery, assault and distribution of controlled substances. She said that taking away commanders’ control of pretrial confinement is “a possibility we absolutely should consider.”

“I completely understand the need for commanders to have the control that they want and have traditionally had,” Escobar said. “But I believe that we do need highly trained legal professionals who are making some of these decisions, because in my view, the status quo hasn’t worked. And in fact, it has failed soldiers.”

Despite facing sexual assault accusations from three women in 2020, Alvarado was not placed in pretrial confinement, according to the news organizations’ investigation. While being interviewed by an Army investigator about the first two allegations, Alvarado admitted that he continued to have sex with one of the women after she passed out. A month later, he sexually assaulted a third woman, which he admitted in text messages to the woman.

But Alvarado’s commanders did not place him in pretrial confinement until more women accused him of assault. A military judge later found him guilty of sexually assaulting two women and strangling one of those two women. He was sentenced to 18 years in a military prison and a dishonorable discharge. Alvarado’s case is currently under appeal. His appeals attorneys did not respond to a request for comment.

“That was shocking to me,” Escobar said. “When you have clear evidence of someone who is a repeat offender, that in and of itself, to me, merits pretrial confinement, and one of the things I do want to know about is why didn’t it happen?”