This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with KUCB and CoastAlaska and was co-published with the Anchorage Daily News. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

On a clear day in May 2019, the tourist season was just starting up in Ketchikan, Alaska, a southeastern city of 8,000 that had become a cruise ship hot spot. For Randy Sullivan, that meant another day — his fifth in a row — of flying sightseeing tours and charters.

Sullivan and his wife, Julie, owned Mountain Air Service, a single-plane family business that had allowed Randy to realize his dream of becoming his own boss. Randy was born and raised in Alaska. He grew up in Ketchikan and had been flying in the area for more than 17 years. He, more than most, knew the dangers of commercial aviation in the state.

“When Randy first started flying up here in Alaska, he learned from some of the best pilots up here and he valued everything they taught him,” Julie said. “Safety was number one for Randy.”

For the 10 a.m. flight, his first of the day, he met his four passengers from the Royal Princess cruise ship at the dock. They boarded his single-engine, propeller-driven, red-and-white floatplane for a tour of Misty Fjords National Monument, 35 miles northeast of Ketchikan. This picturesque landscape, filled with glacial valleys and steep cliffs, is such a popular and crowded flightseeing destination that local operators banded together a decade earlier to create their own voluntary safety measures for flying in the area, including designating radio channels for communication and routes for the planes to follow.

After noon, Sullivan’s de Havilland DHC-2 Beaver was on its way back to town. Another commercial carrier, Taquan Air, was flying one of its own airplanes, also on a flightseeing tour, back to Ketchikan. The two planes collided at about 3,350 feet. The accident destroyed the Beaver and killed all five aboard, including Sullivan, as well as one passenger from the Taquan Air plane. All 10 survivors were injured.

Shannon Wilk lost three family members in the midair collision, including her brother Ryan, who was on Sullivan’s plane.

“I didn’t think the next time I’d be in the same room with him, he would be in a casket,” Shannon said. The crash also claimed the lives of Ryan’s wife, Elsa, and Elsa’s brother, Louis Botha. “I thought he’d get home, we’d keep getting pictures, we’d talk about it and we’d just keep going.”

The National Transportation Safety Board, an independent governmental agency that investigates transportation accidents, eventually determined that the pilots of the aircraft saw each other too late to take evasive action, calling it an example of the limitations of avoiding midair collisions by relying only on what pilots can see through the window.

Fatal midair collisions involving commercial aircraft are practically unheard of in the rest of the country, but in Alaska, there have been five in the past five years alone. In each of them, at least one plane either lacked a key piece of optional safety equipment or wasn’t using it properly.

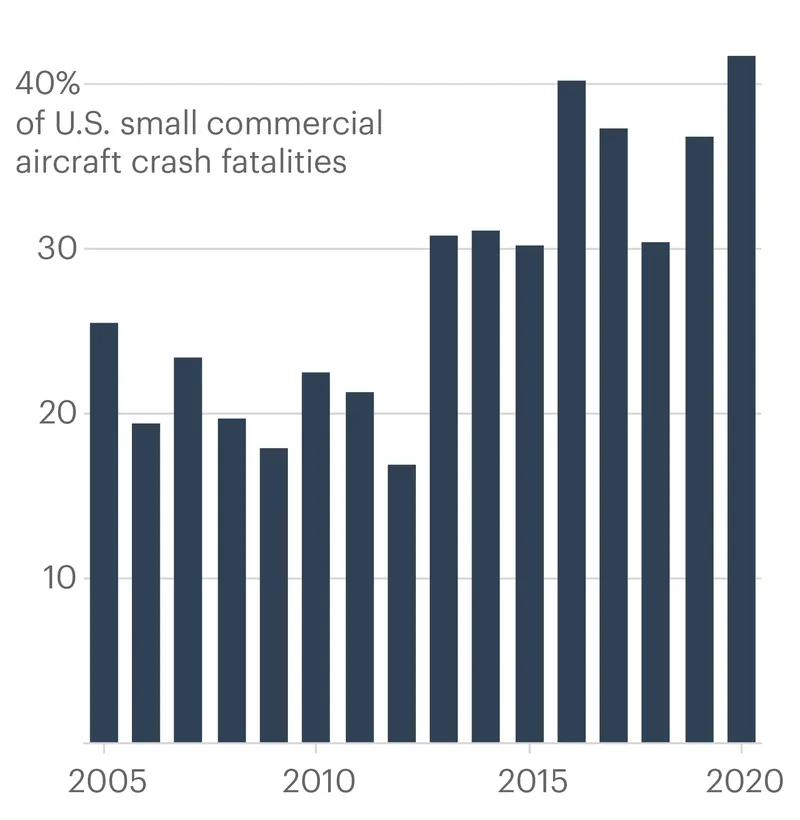

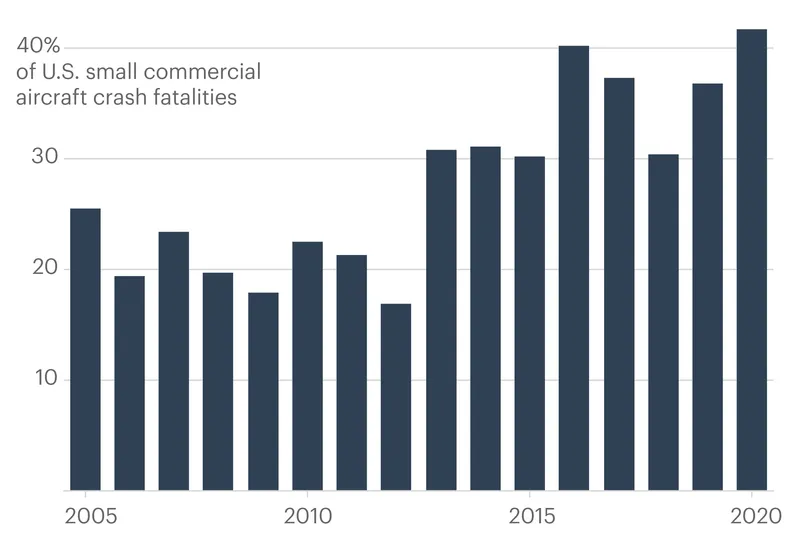

More broadly, in recent years Alaska has made up a growing share of the country’s crashes involving small commercial aircraft, according to an investigation by KUCB and ProPublica. In the past two decades, the number of deaths in crashes involving these operators has plummeted nationwide, while in Alaska, deaths have held relatively steady. As a result, Alaska’s share of fatalities in such crashes has increased from 26% in the early 2000s to 42% since 2016. Our analysis included crashes involving at least one plane or helicopter flying under the Federal Aviation Administration’s typical rules for commuter, air taxi or charter service. (The flight safety record of large air carriers is strong in both Alaska and nationally.)

Alaska’s increased share of aviation deaths can be attributed, at least in part, to its continued reliance on smaller operators, which have worse safety records than large airlines but appear to have waned in popularity outside the state, according to experts.

In interviews with KUCB and ProPublica, federal officials, lawyers and aviation safety experts said the FAA, which oversees air travel in the country, carries much of the responsibility for improving aviation safety in the state. Some say the agency has been slow to adopt rules and provide additional support for the unique conditions in Alaska, leaving pilots and customers to fend for themselves. Some critics also say the FAA has struggled to hold operators accountable for questionable safety track records.

While it has long been known that flying in Alaska is more dangerous than in the lower 48, there are fewer safeguards in the state than almost anywhere else in the country. Because much of Alaska is considered uncontrolled airspace, pilots flying in large areas of the state have limited access to weather and traffic information.

That leaves pilots, many of whom come to the state to get their first commercial flying experience, on their own to navigate rapidly changing weather, mountainous terrain and challenging landings at small rural airports with unpaved, poorly lit runways. Flights can turn deadly even in the hands of experienced pilots.

The state’s share of deaths from crashes involving commuter, air taxi and charter planes made up an increasing portion of the country’s total in the past decade.

The NTSB has been among the most vocal entities pushing the FAA to change its approach in the state. The NTSB is responsible for making recommendations to prevent future accidents, but it lacks the authority to enact them. Following a roundtable meeting in 2019 focused on improving small-plane aviation, the NTSB issued a safety recommendation asking the FAA to review and prioritize Alaska’s aviation safety needs and ensure it’s making progress on implementing safety enhancements.

“I think the FAA has acknowledged that they can do something. They have indicated a willingness to make some improvements,” NTSB Chairman Robert Sumwalt said. “We want them to quit studying this issue. We want them to move forward and implement this.”

The FAA, however, hasn’t implemented many of the NTSB’s recent safety recommendations, including requiring small operators to collect and analyze their flight data in ways that many large commercial air carriers do voluntarily. The NTSB also has asked the FAA to install equipment throughout Alaska that would allow pilots to fly using navigation systems, which is safer than operating by sight, especially when pilots encounter poor weather and visibility.

The FAA declined an interview request but said in a written statement that it had created a new program, the Alaska Aviation Safety Initiative, to look at how the agency is providing resources to the state, their effectiveness, and what more can be done. This group is seeking feedback from the aviation community on the most pressing issues.

“Improving aviation safety in Alaska has long been and remains one of the FAA’s top priorities,” the agency said in its statement. “The FAA’s approach is based on the understanding that safety is a journey, not a destination, and our work will never be done.”

Some experts say additional regulations may not effectively address existing safety concerns and instead put the onus on individual operators to raise their standards.

“Additional rules are not necessarily the immediate answer,” said Jens Hennig, vice president of operations at the General Aviation Manufacturers Association and a member of several FAA rule-making committees. “In many cases, realizing that level of safety gets into many intangible things. What’s the safety culture in the operator? I can’t regulate that.”

Hennig and others say companies can adopt many tools and technologies to improve safety, although they acknowledge that the FAA could do a better job of outreach in Alaska.

One week after the May 2019 crash that killed Randy Sullivan and five others, another Taquan Air floatplane, a type of aircraft that allows for water landings and is popular in Alaska, flipped upon landing in Metlakatla’s harbor and killed 31-year-old epidemiologist Sarah Luna and pilot Ron Rash. It was Rash’s first commuter flight with Taquan.

The NTSB determined the probable cause of the accident was the pilot’s failure to compensate for an off-center tailwind while landing. New pilots, like Rash, were not expected to perform tailwind landings, so they were not taught how to do them during Taquan’s flight training, the NTSB said in its final investigation report. Also contributing to the crash, according to the NTSB, was Taquan’s decision to assign an inexperienced pilot to a destination prone to challenging downdrafts and changing wind conditions.

Taquan declined requests for an interview.

In a letter to the NTSB in 2020, Taquan’s chief pilot said the company had identified significant safety issues, including pilot competency and hazards in water takeoffs and landings. In response, it added pilot competency checks, created checklists to grade new hires on certain tasks, and requires each new pilot to get a minimum of 10 hours of initial operating experience.

Luna’s parents said she knew the risks inherent in commercial aviation in Alaska. But her dedication to her work at the Alaska Native Tribal Health Consortium and her commitment to improving the health of Alaska Native people were greater than her fear. Luna began working in Alaska in June 2018 as part of the consortium’s liver disease and hepatitis program. The flight to Metlakatla, where she’d be meeting patients in person, was her first floatplane ride and her first trip off the road system.

“What happened is not acceptable,” Sarah’s mother, Laura Luna, said in March. “Even though it’s almost two years, it’s like it happened yesterday.”

“Aviation Is Kind of a Lifeline”

Flying in the country’s largest state is unlike flying anywhere else. Because of the state’s small, spread-out population, commercial aviation is dominated by small planes. While larger planes fly to hub communities like Bethel, Nome or Unalaska, they cannot fly to smaller villages because there’s neither the passenger demand nor the infrastructure to support them.

About 80% of Alaska communities are not on the road system, and for the people who live in those places, flying is simply unavoidable. Planes serve as buses for kids traveling to sporting events and other school activities. They transport pregnant women to hospitals where they can safely deliver, and they carry residents to medical appointments not available in their hometowns. They take sexual assault victims to big cities for forensic examinations.

“In Alaska, aviation is kind of a lifeline,” said John Hallinan, a retired FAA flight standards officer who worked at the regional office in Anchorage. “If you shut down service for any particular reason, there’s an impact that’s felt within the community.”

But Alaska lacks infrastructure that is standard in the lower 48. For example, it has 235 state-owned rural airports, of which only 47 are paved. Plus, rural airports are not staffed at all hours of the day.

“What it means is you’re on your own more,” said Tom George, the Alaska regional manager for the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association, a national nonprofit aviation group. “The weather you see out the window is the weather you have to consider and use as your basis for making decisions, as opposed to being able to call up on the radio and find out 50 to 60 miles ahead of you what conditions are like at the moment.”

Despite the state’s inherent dangers, there are limited safeguards in place.

When most people fly commercially in America, they travel on large jet planes from companies like Delta, United and American Airlines. These airlines face the strictest regulations because fatal crashes involving these planes have killed large numbers of people. For example, their pilots typically need to have at least 1,500 hours of flying experience.

While some large air carriers do operate in Alaska, particularly the eponymous Alaska Airlines, there are far more small, often piston or turboprop planes that are well-suited to the state’s unique terrain and limited infrastructure. Pilots for small operators, like Taquan Air, can have as little as 500 hours of experience. They can also fly more hours annually than pilots working for large carriers and are subject to different rest-time requirements.

Nationally, commuter, air-taxi and charter flights were involved in fatal crashes at a far higher rate than large air carrier flights in the past decade.

But it isn’t possible to calculate what the crash rate of small commercial flights was in Alaska compared to the rest of the country because such calculations require knowing the varying amounts of activity between different areas. But the FAA doesn’t release data on the number of flight hours for most of these operations by state or region, and it denied a Freedom of Information Act request from the news organizations because the data is collected and kept by a third-party contractor on behalf of the FAA. KUCB and ProPublica have appealed the denial.

Alaska’s dangerous flying conditions have claimed the lives of numerous high-profile figures, including several politicians.

In 1972, a plane crashed on its way to Juneau carrying then-U.S. House Majority Leader Hale Boggs and Rep. Nick Begich of Alaska. The plane has never been found.

On Aug. 9, 2010, a float-equipped 11-seat airplane carrying guests from a company lodge owned by telecom company GCI to a camp for an afternoon of fishing crashed into mountainous tree-covered terrain about 10 miles outside of Aleknagik, a small city in the Bristol Bay region. The crash killed the pilot and four passengers, including former U.S. Sen. Ted Stevens of Alaska, who had survived a 1978 plane crash that killed his first wife. The four surviving passengers were seriously injured.

The Stevens crash was strongly felt in the state’s aviation community, as he had been a champion for additional funding and Alaska-specific modifications to federal aviation regulations.

“Anybody that lives here knows somebody, it seems, that has died in an accident. People that are this close to a lack of safety are very invested in making it better,” Hallinan said. “Sen. Stevens was very invested in trying to get Alaska up to some kind of level of safety that was on par with the contiguous 48 states.”

Last July, the private plane of Alaska State Rep. Gary Knopp and a chartered plane carrying six people collided south of Anchorage, killing all seven.

And in March, five people — including the Czech Republic’s richest man, billionaire Petr Kellner — were killed on a heli-skiing trip when their helicopter crashed near Knik Glacier.

Combating “Bush Syndrome”

It’s been 41 years since the NTSB first issued a special report on air-taxi safety in Alaska. Data collected between 1974 and 1978 showed that the nonfatal air-taxi crash rate was almost five times higher than the rate in the rest of the nation, and the fatal crash rate was more than double.

The study found three main culprits for Alaska’s high crash rate: “bush syndrome,” defined as a pilot voluntarily taking on unnecessary risks to complete a flight; substandard airport facilities and poor communication of airfield and runway conditions; and inadequate weather information and navigational aids.

Fifteen years later, the NTSB published another safety study specifically about Alaska, which reiterated many of the same concerns, saying pilots and operators faced pressure to provide reliable air service in “an operating environment and aviation infrastructure that are often inconsistent with these demands.”

“I cannot tell you how many phone calls I’ve gotten over the years from people in Unalaska and other parts of the state, calling me personally on my cell phone, saying, ‘Why did you cancel the flight? The winds are not blowing now,’” said Danny Seybert, the former owner and chief executive of PenAir, once Alaska’s second-largest commuter airline, which offered scheduled passenger service as well as charters. PenAir closed in 2020 following a series of bankruptcies and a fatal 2019 plane crash in Unalaska while under the ownership of Ravn Air Group. “There’s a lot of pressure generated from people that live and work in these communities to travel on time and exactly when the flight is scheduled to go, no matter what.”

The FAA has embarked on numerous programs to improve safety in the state. For example, in 1999, the agency began a program to deploy weather cameras that would help provide a near-real-time view of conditions in sites across Alaska. Some 230 cameras have been installed.

One of its most significant efforts occurred between 1999 and 2006, when a joint industry and FAA research project called Capstone equipped aircraft in southeast Alaska and the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta in the western part of the state with Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast systems. The ADS-B tech and its associated ground infrastructure was hailed as a marked improvement over traditional radar systems because it could provide information on weather and the location of nearby aircraft to pilots in areas radar didn’t reach before.

In the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta, the aviation accident rate decreased by 47% between 2000 and 2004, after the Capstone project began.

The FAA deemed the project so successful that it moved to implement ADS-B nationwide. However, the rule only applies to most controlled airspace, which the agency defines in a way that excludes most of Hawaii and Alaska. According to Hennig, the GAMA vice president, Alaska lags far behind the rest of the country in terms of ADS-B-equipped planes.

The cost of ADS-B has gone down over the years. Today, Garmin sells full ADS-B devices for $5,295. The costs are relatively minor for even small operators, especially compared to the cost of their planes.

Some pilots, like Mountain Air’s Randy Sullivan, chose to install the technology because of its safety enhancements.

“[Randy] wanted to have the ADS-B in his plane because he knew how many floatplanes flew in the area and he wanted everybody to see him and to be able to see them,” Julie Sullivan said. “It was very important to have that device in his aircraft.”

Not Enough Deaths to Bring About Change

On Oct. 2, 2016, two pilots departed the Quinhagak Airport in the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta with one passenger, headed for a 70-mile trip to Togiak. This was the pilots’ third of five scheduled flights that day, on a route that would ultimately bring them back to Bethel.

The captain, Timothy Cline, had worked for Hageland Aviation Services Inc. since 2015, while the second in command, Drew Welty, was in his first flying job, having finished flight training that spring at the University of Alaska Anchorage.

Just before noon, the turboprop Cessna 208B Grand Caravan collided with steep mountainous terrain, killing everyone on board.

Cline’s widow, Angela, told investigators that her husband was a fantastic pilot and that she didn’t believe this accident could have happened without some mechanical error, according to notes of the interviews included in the NTSB report. Cline had lost two friends in plane accidents in recent years — one had died two months before — and while he was a little worried, he didn’t have any specific concerns. “The accidents made him more safe and he did not take any chances. [Cline and his wife] had a fantastic life together and he did not ever want to lose that,” according to a summary of the interview. She could not be reached for this article.

The NTSB found the probable cause of the accident to be the pilots’ decision to continue flying into deteriorating weather and visibility. But the agency also cited Hageland’s policies, inadequate training and poor FAA oversight as contributing factors.

In May 2014 — two and a half years before the Togiak accident — the NTSB issued an urgent recommendation for the FAA to audit all aviation operations and training for operators owned by Hageland’s then-parent company HoTH Inc. This followed a 16-month period where the NTSB investigated five accidents involving Hageland aircraft and another incident in which one of its planes went off the runway. The audit resulted in at least 20 changes to company operations or policies, including flight training, aircraft maintenance and evaluating the riskiness of flights.

A number of associated entities — Ravn Air Group Inc., Ravn Air Group Holdings LLC, JJM Inc., HoTH, PenAir, Corvus Airlines Inc., Frontier Flying Service Inc., and Hageland Aviation Services — filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy in April 2020. Many of the assets have since been sold and are now operated by new owners. Representatives for Hageland are winding down the estate of the former operating entity and declined to comment on this story.

The Togiak crash is one of Alaska’s most recent accidents that resulted in NTSB recommendations for improvement, including providing small commercial operators with access to better weather information. Nearly five years after the crash, none have been fully adopted by the FAA.

“The thing is the FAA has always been good at reacting to an accident and establishing a requirement after a major crash,” said Tom Anthony, director of the University of Southern California’s Aviation Safety and Security Program and a former FAA regional division manager for civil aviation security in the Western Pacific.

Experts noted that the nature of crashes in Alaska — typically involving small aircraft with few casualties — partly explains why those accidents get limited attention. When there are enough fatal accidents, said Hallinan, the retired Anchorage FAA flight standards officer, the issue gets more attention, which can help speed up changes in regulations and improve safety.

“Safety comes at a cost. It comes down to the flow of money. It’s awful to think about it like that,” he said. “What it comes down to [is] the expense that you can ask of a 737 operator versus what you can ask of somebody that is operating a couple of [small planes] — there’s just a different level of burden that’s associated with that.”

Sumwalt agreed. “I think perhaps from a policy point of view, once you have a large number of accidents, a large number of fatalities, that’s when it really gets the attention of the right people to make things happen,” he said. “I’m certainly not suggesting we need more fatalities, but I think oftentimes it is blood that gets things done in Washington.”

Unadopted Recommendations

The FAA doesn’t always move forward with the NTSB’s recommendations, and the agencies have disagreed more often in recent years.

A KUCB and ProPublica analysis of NTSB data found the safety board deemed that the FAA didn’t take adequate action on 37% of the recommendations it closed in the past decade, up from 20% in the 2000s and 15% in the 1990s. Other agencies within the Department of Transportation also saw increases over that time, but the FAA, which received far more recommendations than others, had among the highest overall percentages.

“I think it’s important to note that the NTSB doesn’t just pull safety recommendations out of thin air and say, ‘You need to do this,’” Sumwalt said. “These recommendations are written in blood. They’re a result of tragic, tragic accidents and crashes. And so therefore, we think it’s imperative that the regulator move forward with implementing these recommendations and implementing them in a timely fashion.”

Some of the unadopted recommendations relate to cost. The FAA is required by law to conduct a cost-benefit analysis before issuing new regulations; NTSB recommendations are not subject to that requirement. Sometimes the FAA opts to implement voluntary measures or guidance to improve safety rather than making the changes mandatory.

The FAA and NTSB often agree on the nature of a problem, but political forces get in the way of change, said Anthony, the former FAA regional division manager.

“In almost all cases, the FAA is in concordance with the NTSB on these recommendations, but there is frequently political pushback to say, ‘No, we don’t want that regulation. We shouldn’t have it. It’s too expensive. Can’t do it,’” he said. “I was actually shocked when different aviation organizations would say, ‘No, we don’t want to do that’ [to] ideas we felt in our division were obviously needed.”

The FAA said in its statement that it “has a close working relationship with the NTSB” and pointed to its progress on some of the NTSB’s recently released top priorities for 2021 and 2022. For example, the FAA has started drafting rules to mandate safety-management systems, which standardize how companies evaluate and manage risk, for charter and air-taxi operators.

These systems have been required for large air carriers since 2015 but have been voluntary for everyone else. The NTSB first proposed mandating them for small commercial operators in 2016. Currently only 20 of 1,940 small commercial operators nationwide have an FAA-approved system.

Mike Slack, a Texas-based aviation attorney who represents multiple clients involved in Alaska plane crashes, said the FAA has failed to adequately oversee individual companies. He sent a letter to the agency in April 2019 expressing concern that the Taquan Air pilot in a 2018 crash — when a plane carrying 10 passengers from a remote fishing lodge to Ketchikan flew into the side of a mountain — should have been sanctioned by the FAA. Seven months later, FAA officials responded saying the agency had “used appropriate mechanisms to address safety concerns with the pilot.”

In May 2019, the month after Slack’s letter was sent, Taquan Air had two fatal crashes.

“The FAA could have made a difference in preventing those two crashes,” said Slack, who represents Julie Sullivan and her family in their claims against Taquan Air, which he says have been settled. But he said in hindsight it is clear Taquan didn’t do anything meaningful to address safety concerns. “The FAA just looked the other way.”

The FAA said multiple offices examined the performance of the pilot in the 2018 crash and determined the evidence did not support revoking his credentials.

As a result of the collision between Sullivan’s plane and the Taquan plane, a group of 14 Ketchikan commercial operators — including Taquan — modified their voluntary safety measures and agreed to equip all of their aircraft with full ADS-B systems. Taquan also requires its pilots to sign a document agreeing to abide by the new guidelines.

Taquan declined to comment, stating that it is “referring all questions to the NTSB.” Six separate cases filed in federal court by crash victims against Mountain Air, Princess Cruises and Venture Travel, which does business as Taquan Air, were confidentially settled in April. This month, another wrongful death suit filed against Taquan in state court was settled. In that case, brought by the families of two Mountain Air passengers, Taquan denied claims that the company has a “significant, documented history of unsafe operations” and that it was liable for the deaths.

What the Future Holds

Nearly two years after the midair collision in Ketchikan that killed Randy Sullivan and five others, the NTSB board gathered virtually to vote on the findings, probable cause and safety recommendations stemming from their investigation.

Until COVID-19 hit, the NTSB, headquartered in Washington, D.C., had never held a virtual board meeting. But because of the pandemic, this was the agency’s 12th virtual board meeting in 51 weeks, and most staff had replaced their background with the official NTSB backdrop in varying shades of blue.

While both planes were outfitted with full ADS-B systems, the NTSB concluded, the Taquan plane wasn’t broadcasting its altitude because a piece of equipment was turned off. The NTSB was not able to determine who turned off the equipment, but the last time this plane broadcast its altitude was two weeks before the accident. Without this information, the iPad application Sullivan used to look at ADS-B data could not provide visual or spoken alerts of the impending collision. Sullivan’s tablet was destroyed during the accident, so the NTSB was unable to determine whether he was using it or how the application was configured. Taquan’s ADS-B was incapable of providing visual or spoken alerts even if it had been turned on.

Following this accident, the NTSB issued safety recommendations encouraging the FAA to identify high-traffic air tour areas — not only in Alaska, but also in Hawaii and the lower 48 — and require the use of ADS-B technology when flying in those areas. Furthermore, the NTSB asked for all commuter and charter operations, regardless of where they fly, to be fully equipped with ADS-B so that aircraft will be able to see each other’s locations.

“From the earliest days of powered flight, pilots have been taught to avoid other airplanes by watching out for them,” Sumwalt said in a post-board-meeting press release. “This accident clearly demonstrates why that’s just not enough. Our investigation revealed that it was unlikely that these two experienced pilots could have seen the other airplane in time to avoid this tragic outcome.”

Interested Alaskans had to wake up early to attend the meeting, which began at 5:30 a.m. local time. Julie Sullivan was one of those tuned in. She got up around 4 a.m for a pre-board-meeting call for survivors and family members of the victims. She had a friend come over to her house for support, and they watched the meeting together.

It was a relief to see the meeting held, but it was hard for her to watch animations of the crash. Though the NTSB doesn’t fault either pilot for the accident in their final report, Sullivan believes the report holds her husband responsible for a collision he couldn’t have seen coming due to the other plane’s location and technological problems, and that it does not factor in Taquan’s recent history of crashes.

Shannon Wilk — who lost three family members in the same midair collision that killed Randy Sullivan — often feels hopeless and helpless. She doesn’t live in Alaska, and while she doesn’t want anyone else to lose a loved one in an accident, she doesn’t feel like she has the power to change the state’s system, with its history of commercial crashes.

“When you see that these crashes continue to happen and you see that more well-known people have died in these kinds of crashes and still nothing is being done about it, little you is not going to be able to do anything about it,” Wilk said.

Sept. 15, 2021: This story originally misstated the dates of the Capstone program. It began in 1999, not 1996.

Alex Mierjeski contributed research.