As Andrew Montano’s parole date neared, he had two options: spend another year in prison or finish his sentence at a state-funded halfway house.

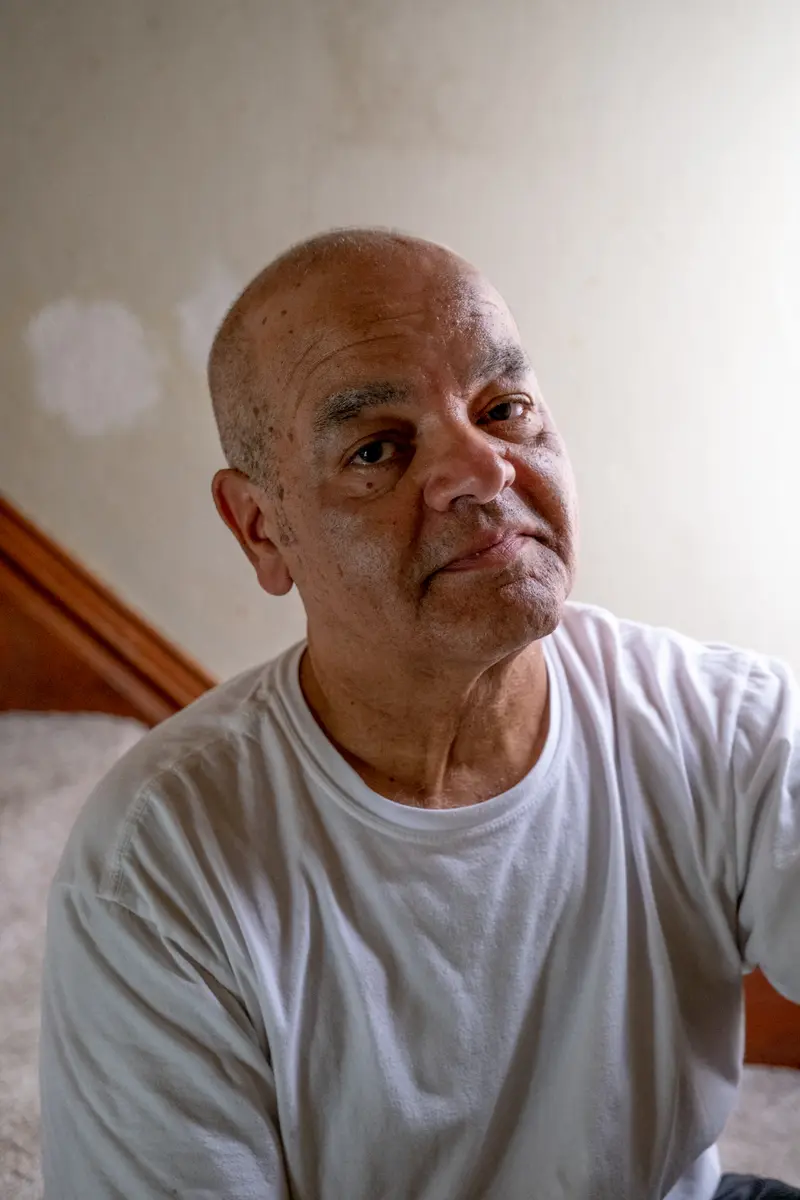

Fellow inmates cautioned him against entering Colorado’s community corrections system, saying it was overly punitive and too often a ticket back to prison. But after nearly 13 years behind bars — his entire adult life — Montano’s desire to embrace his long-term partner and start a career overshadowed those warnings.

In September 2019, he was accepted into a halfway house outside Denver, then owned by the private-prison operator CoreCivic. The rules were strict. But Montano, 35, who was sent to prison in 2007 for assault with a deadly weapon, a crime he committed as a juvenile, was determined to stay on track.

Four months later, during a routine meeting, Montano’s case manager asked if he’d ever been to a location without prior approval from the facility, a violation of the rules. He answered truthfully: On three occasions, while waiting to catch a bus for the hourlong commute back to the halfway house, he’d used a gas station bathroom.

He left thinking the exchange didn’t have much significance. His prior write-ups had been for minor infractions: failing to make his bed, having a box of raspberries in his room and forgetting to sign off on mandatory chores. But later that day, he was told he couldn’t leave the facility, even for work or mandatory classes. For more than a week, he waited.

“Without even a hearing from the halfway house, without being able to even talk to anybody about it, the cops just came and picked me up,” said Montano, who was sent back to prison after a parole hearing. He was released directly onto parole nearly a year later, in December 2020.

“They want us to change, they want us to grow, they want us to learn, they want us to have integrity and to be honest and truthful and a member of society, but we don’t have the chance to be able to (do) that.”

CoreCivic declined to make a representative available for an interview and did not respond to questions sent by email. In a written statement, a spokesperson said, “The staff and leadership teams at our residential reentry centers in Colorado strictly adhere to the policies and standards established by” the Colorado Division of Criminal Justice. “We see our purpose as making sure those in our care are better prepared to succeed no matter where life may take them next. We’re proud of our longstanding track record of delivering high-quality and meaningful residential reentry programs.”

When Colorado formed its community corrections system in 1974, it intended to address prison overcrowding and rehabilitate people in the justice system by providing addiction treatment, job training and other services. Officials saw it as sound fiscal and criminal justice policy: Halfway houses are cheaper to run than prisons, and more assistance would reduce recidivism, meaning fewer people would land back behind bars.

But the reality is more of the people who pass through Colorado’s halfway houses end up incarcerated than rehabilitated. Of every 100 people in a halfway house, only two will be reincarcerated for a new crime, while 26 will fail and likely end up behind bars for technical violations and 14 for running away from a facility.

Among the 57 who do graduate, 22 will be back in the criminal justice system within two years, data since 2009 shows. (Due to rounding, these scenarios add up to 99 people, not 100.)

Colorado’s overall recidivism rate — defined by the Department of Corrections as returning to prison within three years — is 50%, one of the worst in the country, according to a nationwide analysis of recidivism published in 2018 by the Virginia Department of Corrections.

“Is that really the results that we are OK with?” asked Terri Hurst, health justice coordinator for the Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition, a nonprofit group that advocates for policies that decrease reliance on the criminal justice system. “These programs have been operating for years without any sort of transparency or accountability or scrutiny.”

Katie Ruske, manager of Colorado’s Office of Community Corrections within the Division of Criminal Justice, which sets standards for halfway houses and audits for compliance, said her office is wary of requiring certain program completion rates for fear it would come at a cost to public safety. “At times it is in the best interest of other individuals in the program, victims and the community that a person be returned to custody.”

ProPublica spoke with nearly 50 current and former halfway house residents, staff members and experts who attributed Colorado halfway houses’ high rate of failure to numerous and often pointless rules, which can be more punitive than those in prison; a scarcity of employment training; addiction treatment programs that are rudimentary or too brief; and financial costs imposed by the facilities that can sink residents into debt.

As a result, Coloradans are, in effect, paying twice: first to fund residents’ time in halfway houses and again when they end up behind bars. From 2019 to 2021, more than 2,000 people were sent from a halfway house to prison, where the cost to incarcerate them more than doubled, to $56,000 a year, according to a Department of Corrections spokesperson.

“By and large,” said state Rep. Leslie Herod, a Denver Democrat, halfway houses “have become just another place to warehouse people, to profit off of people’s misfortune.”

“The Insanity of This System”

There are three ways people typically end up in Colorado’s 26 state-funded halfway houses. Diversion clients are sentenced by a judge to community corrections in lieu of jail or prison. Transition clients apply to finish their prison sentence there. And some former prisoners are required to complete a halfway house program as a condition of parole.

The time it takes to complete a program varies, but it averages around eight months. And afterward, many diversion clients remain on “non-residential status” for an additional nine months on average, according to a 2018 state report, meaning they no longer live at the facility but report to their case manager and are subject to drug and alcohol testing. (The state’s data excludes those who participate in lengthier specialty treatment programs.)

Over the past three years, Colorado averaged about 6,000 halfway house stays annually. A majority of Colorado’s halfway houses are owned by companies specializing in detention and community-based supervision. Three — CoreCivic, Advantage Treatment Center Inc. and Intervention Inc. — operate 15 of the 26 state-funded facilities.

This fiscal year, community corrections will receive $87.7 million in state funding — or nearly 16% of the state’s public safety budget — to cover operational costs and treatment services. The facilities aren’t required to report in detail to the state oversight agency or lawmakers what they do with the funding.

“There are, at times, various things that we require them to show us, but there isn’t one standard,” Ruske said. “We’re not a financial auditing entity.” Every three years operators are required to hire a public accountant and submit a financial report to the state, but a majority haven’t filed a report since 2017.

Until July, facilities also charged rent to residents, about $510 per month — $17 a day — for a room shared with three to 24 people. During fiscal 2020, facilities collected approximately $15 million in rent.

Although state taxpayers provide most of their funding, the state delegates much of the oversight to local community corrections boards that vary in their makeup, protocols and oversight practices. Board members are typically appointed by county commissioners and include mayors, parole officers, law enforcement, prosecutors and judges.

This local control gives facilities broad authority to establish rules and program requirements for individual halfway houses, creating a patchwork of policies across the state.

A special government audit in 2021 spurred by citizen complaints found that a Colorado Springs facility run by ComCor Inc. had an “excessive” number of rules that residents had to abide by, some “disrespectful in nature.”

Mark Wester, executive director of ComCor, said the facility has “moved to a more supportive therapeutic approach to client care” in response to the audit. He said it also established a committee to review rules, as well as the sanctions it imposes.

Residents at halfway houses owned by the nonprofit Intervention Community Corrections Services are prohibited from possessing candles, gift cards, debit cards or cash, according to a client manual. And in interviews, former residents said they’re barred from wearing tank tops, having cellphones or driving. Failing to “follow a direct order by staff” and returning to the facility a few minutes late are also violations, according to the manual.

The current and former residents of some Colorado halfway houses who spoke to ProPublica acknowledged they need to account for their whereabouts but said such requirements are sometimes impossible to comply with, especially when relying on public transportation.

“If you’re a minute late, they’ll try to write you up. But sometimes due to weather or the bus or something like that, you might not be able to make it if those are unforeseen circumstances,” Montano said. “Their response is, ‘Well, you better start running.’”

Punishment for violating the rules also varies, from added chores to a return to prison.

A person can be expelled from a program for “any reason or for no reason at all,” a 2012 law says. If a diversion client pleads not guilty to a violation, a hearing is held to determine their punishment. But, as noted by numerous state audits, documentation of such hearings — and the outcomes — are inconsistent and lack detail.

ProPublica obtained through a public records request incident reports from all Colorado halfway houses in operation during a three-year period. They showed residents facing serious discipline for expressing suicidal thoughts, not reporting a traffic ticket and driving without permission. If they’re kicked out of a program, most end up incarcerated. One resident was terminated and sent to jail because he was suspected of stashing a gun in the woods even though police didn’t have enough evidence to arrest him.

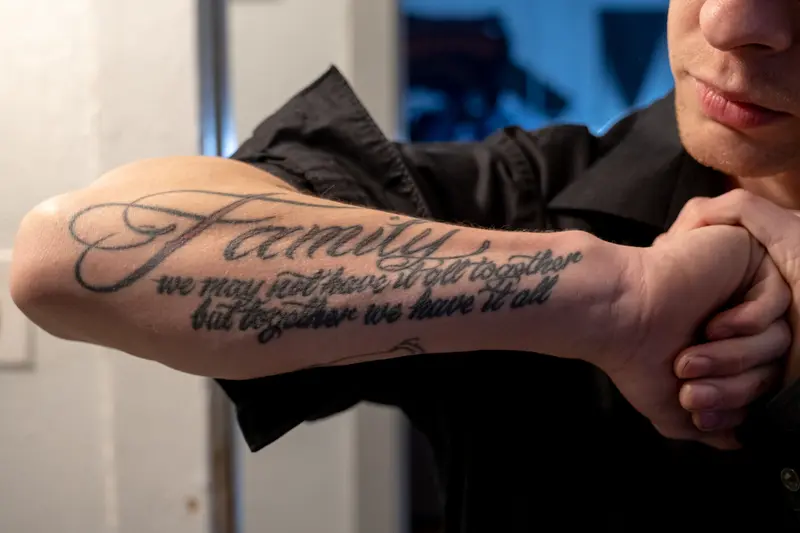

John Sherman went 34 years in prison without a write-up. But that changed within days of being released to a for-profit halfway house in Denver.

On his second day at CoreCivic Dahlia, the 66-year-old was given permission to travel to Walmart to buy clothing. When he entered the store, more than a dozen family members were waiting to surprise him. Loved ones pulled him in for hugs, stuffing money and gifts into his hands. His sister interrupted the reunion, frantically reminding Sherman that he needed to report his arrival at the store. But the customer service desk wouldn’t let him use its landline, and he missed his deadline by a few minutes.

Strict protocols track residents’ movements. Their route must be approved with a deadline to reach their destination. In some halfway houses, residents aren’t allowed to have a cellphone, forcing them to find a landline to report back to the facility.

In the weeks that followed, Sherman, whose sentence was shortened by former Gov. John Hickenlooper, received seven more write-ups for failing to call the facility. He said he lived with “intense dread that I’m going back to prison.”

Research shows someone with Sherman’s track record is positioned for success after prison: He had family support, didn’t struggle with substance abuse and had a place to live. He would ultimately succeed, but he said it was only because he stayed away from the facility and its rules as much as he was allowed.

“The halfway house doesn’t care if you leave or succeed,” said Sherman, who completed his program in January 2021. “Somebody’s gonna fill that bed no matter what.”

Roger Jarjoura, a researcher and senior adviser with the American Institutes for Research’s National Reentry Resources Center, said structure and supervision are key aspects of any reentry program, but arbitrary rules coupled with excessive supervision increase the likelihood a person will fail. The NRRC, which is funded by the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Assistance, provides technical assistance to reentry organizations and local and state governments to improve recidivism rates.

“That’s the insanity of this system: People who have already shown that they are not great with structure or rules have to follow way more rules than a typical person would,” Jarjoura said. “Supervision can be effective when it’s connected to the right kinds of treatment and the right kinds of support.”

Kathryn Otten, who until 2016 directly oversaw two halfway houses as division director of Justice Services in Jefferson County, said the facilities’ punitive policies set residents up for failure.

The Jefferson County facilities — one of which recently closed — are run by Intervention Community Corrections Services, under the umbrella organization Intervention Inc., which currently operates four other halfway houses in Colorado.

Otten recalled that after a bathroom was defaced at one facility, “instead of getting to the bottom of it to figure out who did it,” staff put all residents on lockdown. “They made everyone stay in, miss work, miss everything,” she said. The facility, which like all Colorado halfway houses controls residents’ finances, then took money from everyone for repairs.

“We stepped in at that point and said, ‘No, you can’t do that,’ and ensured that residents got their money back,” said Otten, who in 2016 became the county’s director of housing, homelessness and integration.

ICCS’ executive director, Brian Hulse, declined to be interviewed or respond to questions sent by email. In a written statement, he said: “We use evidence-based and evidence informed practices to maximize desired outcomes and positively impact the lives of our clients. We are proud to serve our community in this capacity.”

Wendy Sawyer, research director for the Prison Policy Initiative, a research and advocacy organization, said it’s not just the number of rules or how arbitrary they can be, “but the way that the person who’s supervising them chooses to apply those rules.” She added, “There’s a ton of discretion.”

Broderrick Rimes, a former ComCor security manager who left the company in July 2021, said the enforcement of rules was often dictated by what was financially beneficial to the facility. When clients broke a rule, staff contacted the billing department to see if they had paid their rent.

“If they’re up to date on their rent, they’ll never get sent back to jail or prison,” he said. But if they owed money they would be kicked out and replaced by someone who could pay. “That is the mentality of community corrections.”

A 2017 audit of ComCor by the Office of Community Corrections found “a clear pattern of inappropriate application of serious sanctions to minor behavioral violations, especially those related to financial matters.”

Wester, who noted the audit occurred before he joined ComCor in 2019, denied that staff check whether clients have paid their rent before disciplining them.

Staying Clean

One in five residents of Colorado’s halfway houses is completing a sentence related to substance abuse, according to the state’s three most recent annual reports.

Nearly a dozen current and former residents and staff members from various facilities told ProPublica that the treatment they received was rudimentary, redundant and sometimes overseen by inexperienced staffers. Residents receive treatment of varying length and intensity, from drug and alcohol classes sometimes taught by halfway house staff to 90-day intensive residential treatment.

Shawn Brndiar, a licensed clinical social worker and addiction counselor in Centennial, Colorado, said the three-month addiction programs are not long enough. Effective programs are typically longer than a year, he said.

“Addiction doesn’t start in a vacuum. It’s not like just one day, somebody woke up and said, ‘I’m going to start shooting heroin,’” said Brndiar, who has been an addiction counselor for nine years. “There’s a whole history of things that happened to this person.”

An analysis by the MacArthur Foundation and the Pew Charitable Trusts found that the intensive residential treatment programs in Colorado’s community corrections system were an inefficient use of taxpayer money and “not very effective at reducing recidivism.” They received the lowest score among 21 criminal justice programs that were evaluated, including those offered in jail or prison.

Over the past five years, 66% of residents enrolled in intensive residential treatment programs graduated.

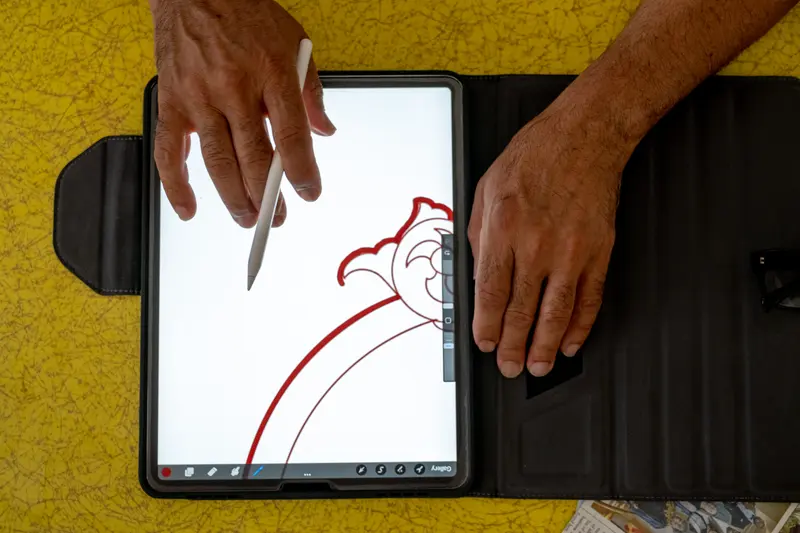

Michael Anthony Martinez, 29, said he benefited from skills he was taught to manage anger and codependent relationships while in intensive residential treatment in 2020 and 2021. But he said drugs were easily accessible at the Sterling facility owned by Advantage Treatment Centers and he failed out.

ATC did not respond to requests for comment.

The most recent audit of the facility, in 2019, found it was out of compliance for controlling contraband entering the facility.

After failing multiple drug tests, Martinez, who was a diversion client, was sent to prison.

He spent 10 months in prison before being released on parole. After a few months at a sober living home and another 90-day intensive drug treatment program — his third — at a different halfway house, he graduated in July 2022 but was transferred back to the Sterling facility, according to state documents.

“I’m ready to be (a) successful man and show everybody that I can do something right,” he said. “Because this is just sickening. In and out, in and out.”

Requiring people to repeat ineffective programs is a way for companies to boost their profits, Brndiar said.

“It’s a business,” said Brndiar, who is a professor at Metropolitan State University of Denver. “There’s an incentive to keep people in this cycle over and over and over and over again because either way they’re going to get money.”

While some programs provide financial assistance to help with program fees, many residents are required to reimburse the facility once they obtain employment. In fiscal year 2021, 2,521 residents graduated owing on average $1,076, according to the state’s annual report.

At some ICCS facilities, residents receive treatment for mental health and addiction provided by a related company, Behavioral Treatment Services, and are sometimes required to pay out of pocket for those services, according to Otten. The CEO of ICCS’ parent company, Intervention Inc., Kelly Sengenberger, is on the BTS board of directors and was listed as BTS’ owner in state documents from 2017 to 2019. The companies listed the same business address with the state.

Ruske, of the state’s oversight agency, told ProPublica that the financial relationship was not disclosed to the state. ICCS’ contract with the state requires disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. Neither Sengenberger nor BTS responded to emailed questions.

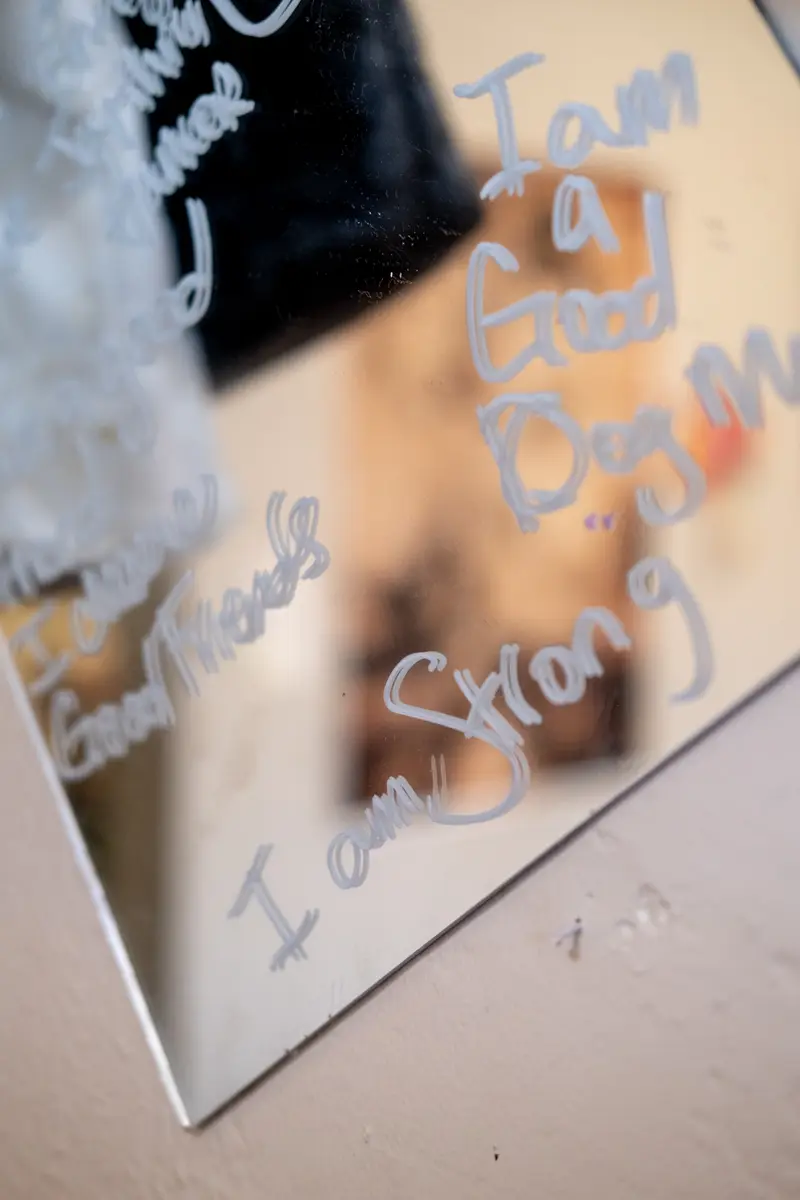

Alycia Samuelson completed a three-year residential halfway house program in 2014 at ICCS. She said part of her treatment was overseen by interns doing outpatient rounds who were ill-equipped to help people who, in her case, had experienced decades of substance abuse and trauma.

“All I’d ever known was addiction,” she told ProPublica. “My mom had given me my first line of cocaine when I was 13. So I didn’t know a lot of the skills for how to be a successful person.”

Samuelson ultimately graduated from the residential program and, after being homeless for more than a decade, moved into her own apartment. And for the first time in her adult life, she wasn’t using meth. But less than a year later, she relapsed and failed a drug test. The facility brought her back into the program then sent her to prison.

“Addiction is a relapsing disease,” Brndiar said. “People relapse, and to make your first move the most severe punishment? It only re-traumatizes the person going through this process.”

Recovery from drug addiction is a long-term process and frequently requires rounds of treatment, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse. As with other chronic illnesses, relapses can occur and signal a need for additional treatment, research shows.

When Samuelson was released from prison, she was homeless, fell back into drug use and ended up in another halfway house in 2018. Six months into her program she said she was suicidal. In a matter of weeks, her husband left her, her son was diagnosed with colon cancer and a friend overdosed in the facility and died. Samuelson said staff ignored her struggles so she ran away.

“I said I felt like I’m gonna take my life and I thought they were going to call the ambulance and they didn’t,” said Samuelson, 47, who now lives in Denver. “I literally ran from the halfway house to save myself.”

A 2020 law reduced the charge for escaping from a halfway house to a misdemeanor, instead of a felony, for those serving time for nonviolent crimes, meaning Samuelson wasn’t returned to prison. In 2021, 910 halfway house stays, or 24%, ended when the person ran away from a facility, a sharp increase from 2012 when the rate was 12%, according to state data.

Those with a diagnosis of mental health issues are significantly more likely to fail out of community corrections, according to a 2018 analysis by the Colorado Division of Criminal Justice’s Office of Research and Statistics. Only 48% graduated between 2014 and 2016, compared with 61% of those without such a diagnosis. But a diagnosis had little to no effect on whether the person committed a new crime in the future, the report found.

“If all they have are other people who are part of the criminal justice system and underpaid, underqualified people providing treatment, they’re not going to (get what) they need,” Brndiar said.

Finding a Job

Employment is key in determining whether someone stays out of prison, according to academic studies and reports by Colorado’s Division of Criminal Justice. Yet state audits show employment services are some of the least-available resources in state halfway houses.

People entering the facilities face challenges getting a job. Some haven’t worked in decades. Others were juveniles when they entered the corrections system and may never have held a job. A criminal record, lack of transportation, addiction and mental health issues can further complicate finding employment.

“If they don’t have a means to support themselves, they’re going to figure out how to do that,” said Jarjoura, the recidivism expert. “People don’t choose crime. That’s how they learn to survive.”

Limited scope audits by the Office of Community Corrections show that of the facilities where employment services were assessed from 2015 to 2018, only two were in full compliance with state standards. The agency stopped evaluating the quality of employment services in 2018, after a new manager took over OCC.

“The future strategic goals of the office include developing processes for reviewing compliance with the additional Colorado Community Corrections Standards not currently reviewed,” OCC said in a written statement.

There’s pressure to start working immediately, residents said. They must pay for rent, hygiene products, clothes and transportation. On top of that, they pay restitution, court fees, child support, state and federal taxes and set aside savings in order to graduate from the program.

The urgency makes the job search more about the facilities getting their money than residents’ long-term success, former staff and residents said.

“You threaten the client, you say: ‘You better get a job, you better work, you’ve got another week. If you’re not working in another week, you’re going to go back,’” said Rimes, the former ComCor security manager.

Otten said residents at the two Jefferson County facilities were pressured to accept the first job they found in order to start paying rent. The jobs were often low paying, ultimately slowing their reentry process.

She said among the biggest barriers to employment is offenders’ inability to spend money without prior approval from the facility, which can sometimes take weeks. Facilities have power of attorney over resident’s finances, and getting caught with a debit card or cash can lead to discipline, “even if that money is to buy steel-toed boots in order to get a job,” she said.

When residents found jobs, they were sometimes denied by the facility, Otten said.

One resident wasn’t allowed to work a high-paying construction job because it was out of cellphone range, Otten said. Another was prohibited from working at a law firm because it was located in a house, not an office building. “They sent her to work at the diner, waitressing,” she said.

Before becoming director of justice services, Otten ran workforce training programs for formerly incarcerated people at the Colorado Department of Labor and Employment.

“Community corrections folks were always more difficult to work with because of the rules and regulations that didn’t allow (residents) to work in higher-wage jobs in demand industries,” she said.

More Money, Same Outcome

In response to recommendations from the Office of Community Corrections, lawmakers this year approved increased funding for Colorado’s halfway houses.

This fiscal year, operators will receive $67 per day for each occupied bed, up from $47.96. The increase requires facilities to stop charging rent, per their state contracts, but state law doesn’t prohibit it.

Lawmakers also approved funding that for the first time will be tied to performance, including graduation and recidivism rates. Meanwhile, the state’s oversight agency has made it easier to qualify for the extra dollars by changing its definition of recidivism.

Historically, recidivism was defined as a criminal filing within two years of graduating from a halfway house.

The new definition: a felony conviction within two years of entering a facility.

For example, ComCor’s recidivism rate under the old definition was 41%, according to the state’s data dashboard; under the new definition, it’s 3%.

Only three facilities that were eligible did not qualify for the additional funding.

“They moved the bar even lower than it was before,” said Hurst, the Colorado Criminal Justice Reform Coalition policy expert. It’s unlikely someone charged with a felony will get through the court process within the two-year timeframe, she said.

Ruske, of the Office of Community Corrections, told ProPublica that if facilities are not trying to improve, the state has the authority to cut their funding to “encourage participation.” OCC last exercised that authority in 2016.

Although ComCor qualified for the new incentive funding tied to recidivism, Wester, the executive director, doesn’t think a facility should be held accountable for its former clients’ success or failure after they leave a community corrections program.

“We do everything we can to work with clients, but once (they) get out, I mean, they control much of their lives and they start making decisions,” he said.

Hurst said she’s heard facility operators make that argument many times but believes it ignores the purpose of halfway houses to provide treatment and support so people stay out of the criminal justice system.

“That’s the whole premise of community corrections,” Hurst said. “So if the outcome is that people are ultimately ending up in prison, in jail, anyway, that’s concerning.”