Our reporting on the relationship between Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas and Harlan Crow, a Texas billionaire and Republican megadonor, has touched off a national conversation about the ethics of the Supreme Court. Other news organizations have stepped up their scrutiny of the high court, and our stories have been cited thousands of times in editorials, op-eds and Congress.

The lavish travel Crow funded and the previously undisclosed real estate deal and tuition arrangements between Crow and Thomas that our reporting revealed has become fodder for the dueling narratives of American politics.

“Today’s report continues a steady stream of revelations calling Justices’ ethics standards and practices into question,” Senate Judiciary Committee Chair Dick Durbin, D-Ill., said in response to our story about the tuition payments. “I hope that the Chief Justice understands that something must be done — the reputation and credibility of the Court is at stake.”

Sen. Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., shot back at a recent hearing of the committee: “This is an unseemly effort by the Democratic left to destroy the legitimacy of the Roberts court. There’s a very selective outrage here.”

The furor seems destined to continue. And so we thought it might be useful if we said a bit more about the origins, timing and criticisms of our journalism on this subject.

Editors at ProPublica have been thinking about the need to look more closely at the state and federal judiciary for years. One byproduct of our gridlocked legislature is that judges have come to play a larger and larger role in people’s lives, from health care policy to affirmative action to abortion.

Last year, we worked with our partners at The Lever on a story revealing that a wealthy industrialist had gifted $1.6 billion to a group run by Leonard Leo, a key player in assembling the Supreme Court’s conservative majority. Reporting in recent years has shown Leo running dark money groups focused on influencing the judiciary.

We admired the work done by our colleagues, notably at The Wall Street Journal, which found federal judges were ruling on a surprising number of cases in which they had a financial interest. A New York Times piece on what appeared to be a coordinated effort to befriend and influence Supreme Court justices also caught our eye.

But the federal judiciary still struck us as a relatively under-scrutinized branch of our democracy. So late last year, we assigned Justin Elliott, Josh Kaplan and Alex Mierjeski to take a look. The team filed a raft of public information requests for records on courts across the country.

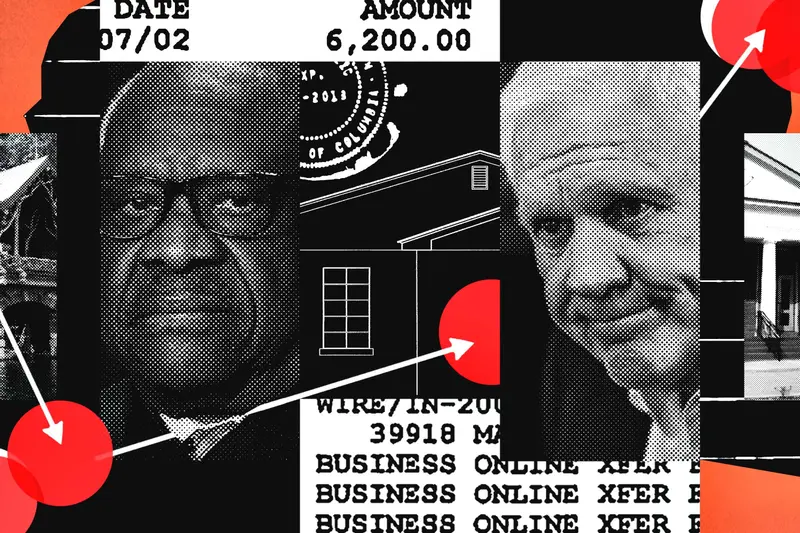

Early on, the ProPublica team decided to focus on the highest court in the land and began by scouring the annual disclosure forms filed by the justices. Research in some obscure corners of the internet brought to light evidence that Thomas had made at least one trip on Crow’s plane that had not been disclosed. As the team dug deeply over several months, the reporters amassed a detailed picture of what turned out to be decades of unreported trips the two had taken in the United States and overseas.

The weekend after that story appeared, a reader called one of the reporters to say Crow may have renovated Thomas’ mother’s house in Savannah, Georgia. A cursory search of online records showed that Thomas’ mother’s home had, in fact, been sold to a limited liability corporation that we quickly linked to Crow. The reporters flew to Savannah, collected public records from the appropriate local government offices and interviewed neighbors. Once we established that the justice had sold properties to Crow and confirmed Thomas had never disclosed the deal, we published.

Soon after that second piece appeared, the reporters turned to another tip that came in after the initial story published: that Crow had paid tuition for Mark Martin, Thomas’ grandnephew, who the justice had legal custody of and has said publicly he was raising as his own son.

The tip was that Crow had paid tuition at two private boarding schools. One of the schools had spent a period in bankruptcy, and the reporters reviewed hundreds of pages of court filings. They found a bank statement that showed Crow had paid a month’s tuition for Martin. A former administrator at the Georgia school who had access to school financial information told us in an on-the-record interview that Crow had paid a full year of tuition. He also said that Crow had told him that Crow also paid Martin’s tuition at Randolph-Macon Academy in Virginia.

Crow has issued statements about his relationship with Thomas that we’ve included in our stories. He acknowledged that he’d extended “hospitality” to the Thomases, but he said that Thomas never asked for any of it and it was “no different from the hospitality we have extended to our many other dear friends.” He said he purchased Thomas’ mother’s house to preserve it for posterity. And in response to questions about the tuition payments, his office said, “Harlan Crow has long been passionate about the importance of quality education and giving back to those less fortunate, especially at-risk youth.” He has not disputed any of the facts in our reporting.

The timing of the stories have prompted some to wonder if ProPublica had the information about the trips, the house and the school tuition in hand at the outset and spaced out publication to achieve maximum impact. We did not.

This story developed as much investigative journalism does — organically, with one finding leading to the next. Tips like those that pushed the Thomas story forward are essential to our reporting. It’s why ProPublica publishes the email addresses of its editorial staffers to help sources connect with us. (If you have a tip for our newsroom, we have details about how to get in touch.)

Our reporting on the courts continues, and we stand ready to look into questions about judges or justices of any ideological stripe.

The response to our investigation has been generally positive, with leading commentators on legal affairs using it to examine and explain why the nation’s highest court has no binding ethical code. As is always the case, our work also has its critics.

The Wall Street Journal’s editorial page has also criticized the reporting on Thomas in a series of columns by James Taranto, its editorial features editor.

Boiled down, his argument is that Thomas was not required to disclose the tuition for Martin and his omission of the sale of his mother’s house from his forms was an innocuous mistake. The experts we quoted, Taranto and several other critics contend, simply got it wrong.

We understand that experts may hold differing points of view about complicated subjects. It’s why we reached out to ethics lawyers who had served in Republican and Democratic administrations. We specifically sought out attorneys with expertise on the Ethics in Government Act, the federal disclosure law that binds justices and many other federal officials. We also talked to retired and currently serving federal judges about how they would handle comparable situations. Their views are reflected in our stories.

Every ethics expert we have spoken with said Thomas was required by law to disclose the gifts or transactions that we’d found.

In his columns, Taranto has used an increasingly inaccurate shorthand to refer to our work. He began by saying we had committed a “sloppy reporting error” in our story about the real estate transaction. Later, he said we were “comically incompetent” and described our story on the real estate transaction as “error-filled.”

Despite his assertions, none of Taranto’s columns cited an error in our stories. We sent an email asking him to identify the multiple facts he believes we’ve gotten wrong. He sent back a link to his first column. When we replied that the piece did not cite a single factual misstatement from our story, he ghosted us.

Perhaps more importantly, we sent detailed questions to Thomas and invited him to explain his decisions. He declined to do so but issued a statement the day after the first story appeared that said he and his wife, Ginni, counted Harlan and Kathy Crow as “among our dearest friends.” Thomas said that early in his tenure on the court, he “sought guidance from my colleagues and others on the judiciary and was advised that this sort of personal hospitality from close personal friends, who did not have business before the Court, was not reportable.”

The debate over that statement continues in Congress and in public. Neither Crow, Thomas nor anyone else has identified a factual error in any of the stories. Thomas has not responded to any of the questions we sent about each of our subsequent stories, and he has not commented in public since his initial statement.