ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up to receive our biggest stories as soon as they’re published. This story was co-published with the Guardian.

On his first day in office, President Joe Biden announced that his administration planned to scrutinize a Trump-era decision to allow the continued use of chlorpyrifos, a pesticide that can damage children’s brains. And with great fanfare, the Environmental Protection Agency went on to ban the use of the chemical on food.

“Ending the use of chlorpyrifos on food will help to ensure children, farmworkers, and all people are protected from the potentially dangerous consequences of this pesticide,” the head of the EPA, Michael Regan, said in his announcement of the decision in August 2021. “EPA will follow the science and put health and safety first.”

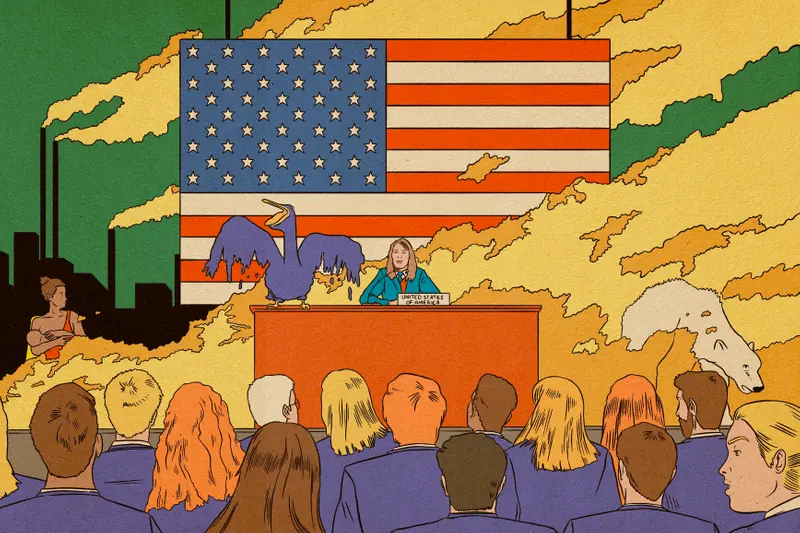

Yet when officials from around the world gathered in Rome last fall to consider whether to move forward with a proposed global ban on the pesticide, chlorpyrifos had a surprising defender: a senior official from the EPA.

Karissa Kovner, a senior EPA policy adviser, is a key leader of the U.S. delegation at a United Nations body known as the Stockholm Convention, which governs some of the worst chemicals on the planet. Chlorpyrifos is so harmful that the American government not only banned its use on food but also barred the import of fruits and vegetables grown with it. But Kovner made it clear that the U.S. was not ready to support taking the next step through the convention to provide similar protections for the rest of the world.

At the meeting, Kovner questioned whether the pesticide is harmful enough to merit being included on the Stockholm Convention’s list of banned and restricted chemicals. Some attendees said Kovner’s intervention ultimately stalled the effort.

“Her role is essentially to slow the process down and stop things from getting listed,” said Meriel Watts, a New Zealand-based scientist and pesticide expert who attended the Rome meeting and has participated in the Stockholm Convention process for years.

In an interview with ProPublica earlier this year, Kovner said that those who see her as unconcerned about public health and the environment misunderstand her job. “While I happen to work at EPA, what I represent is the United States,” said Kovner. “We are but one of many wheels — or one of many spokes in the wheels — of the U.S. government that works on” persistent pollutants that accumulate in living things.

Other spokes in that wheel include the Department of Commerce; the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, where Kovner worked decades ago; and the Department of Agriculture, whose secretary, Thomas Vilsack, has raised questions about the EPA’s decision to cancel all food uses of chlorpyrifos.

Kovner said the rules governing restrictions under the Stockholm Convention are different than those that regulate chemicals in the U.S. She also said the positions she and her colleagues take at the Stockholm Convention are guided solely by scientific research. “We bring all of our science to the table,” she said. “It’s very hard to imagine that the convention has not been advanced significantly as a result.”

The EPA echoed Kovner’s comments that the criteria for restricting chemicals internationally are different than those EPA follows domestically. An agency spokesperson noted in a written statement that Kovner does not conduct the scientific review of chemicals. Kovner is just doing her job at the Stockholm Convention, the EPA spokesperson said, and is “a leader in advancing our U.S. domestic policies at the international level.”

For many of the experts who attend the Stockholm Convention meetings on behalf of polluted communities, though, Kovner and the whole U.S. delegation represent a puzzle. The EPA’s mission is to protect public health and the environment. “It has seemed so strange to me to see the U.S. EPA at these international meetings so determined to derail the listing of chemicals,” said Pam Miller, the executive director of Alaska Community Action on Toxics.

The U.S. is home to powerful chemical companies and lags behind much of the rest of the world in banning toxic compounds. The EPA says the U.S. delegation to the convention has supported restrictions on some chemicals. But observers say that the support has often come after countries agreed to carve out exemptions important to American industries.

“Many developing countries look at it [the Stockholm Convention] as an opportunity for greater protection,” said Joe DiGangi, a chemical expert who began attending the yearly meetings of the Stockholm Convention in 2005. “The U.S. often looks at it as a threat to their industry.”

Globe-Trotting Pollutants

More than two decades ago, the United Nations adopted the Stockholm Convention because individual countries’ restrictions could not prevent certain toxic chemicals from traveling across borders. Lofted into the air by smokestacks, gradually released from consumer products, and transported to the far reaches of the globe by water and wind, these persistent chemicals can accumulate in the environment, animals and humans. Often these pollutants wind up in the arctic, where they can be especially damaging because they get trapped in snow and ice and become less likely to dissipate. As a result, the Indigenous peoples of the arctic have high levels of these chemicals in their bodies.

Persistent organic pollutants, as these chemicals are called, lodge in fat cells, allowing them to spread from contaminated animals to anything that eats them. Humans sit at the top of this polluted food pyramid, and we can pass the chemicals to our babies through the umbilical cord before birth and through breast milk afterward.

The aim of the global treaty, which entered into force in 2004, is to protect people around the world from the most toxic of these pollutants. By banding together, countries gained increased leverage over the powerful companies that make and use the chemicals. The U.S. government, which has a long history of refusing to be bound by international treaties, has not ratified the Stockholm Convention, so it can only participate as an observer. But even without having a vote, American officials have been hugely influential.

The U.S. is known for throwing a wrench into the international convention’s efforts to restrict pollutants. “They’re usually seen as a country that raises objections to the regulation of chemicals,” said David Azoulay, a managing attorney at the Center for International Environmental Law who has attended meetings of the convention since 2011. Because the U.S. is not a voting member, Azoulay said, much of its efforts take place outside of the usual channels. “They are very active in the corridors,” he said.

Inside the meeting rooms, the U.S. often raises technical questions about the evidence supporting restrictions and advocates for exemptions. An EPA spokesperson told ProPublica that the U.S. “supports carefully crafted and narrowly tailored specific exemptions.”

At the most recent meeting held in late May in Geneva, more than 120 countries agreed to add two plastic additives to the list of substances slated for global elimination. The U.S. delegation went on record opposing the ban of one of them, a flame retardant chemical called Dechlorane plus, which has been shown to damage the liver and interfere with development in animal experiments.

Miller, of the Alaska environmental group, said she witnessed Kovner at an earlier meeting consulting with a representative of the aerospace industry and then suggesting exemptions to the proposed Dechlorane plus ban on their behalf.

Asked about the interactions, Kovner told ProPublica: “I talk to a wide range of stakeholders and that is absolutely 100% my job.” She added, “There are indispensable components of our NASA program that contain Dechlorane plus.” At the urging of Kovner and others, the Stockholm Convention’s member countries agreed to allow for certain uses of the flame retardant in replacement parts for the aerospace and auto industries.

Kovner was also in close contact with a powerful chemical industry trade group about the other compound, UV-328, which prevents plastic from deteriorating in sunlight. In order to be restricted under the Stockholm Convention, a pollutant must be shown to travel long distances. UV-328 was the first chemical that the convention decided met that criteria because it is transported by plastic debris that accumulates in bodies of water around the globe and in the migratory birds that eat it.

In April 2019, a representative from the American Chemistry Council, a trade group for chemical manufacturers, emailed Kovner to alert her of the proposal to consider limits on UV-328 under the Stockholm Convention based on its presence in microplastics, or pieces of plastic debris about the size of a sesame seed that accumulate in the environment and contain multiple chemicals.

“Wow — that’s quite a precedent. Holy moly,” she responded in an email, as the Greenpeace publication Unearthed has reported.

The chemical trade group representative wrote that they had seen several presentations about “getting microplastics into Stockholm.”

“Welcome to our future,” Kovner responded.

In March 2021, two months after the Stockholm Convention decided that UV-328 cleared the first hurdle to be considered for a ban, Kovner told attendees at a conference organized by the American Chemistry Council that the U.S. government disagreed with that decision and questioned the science behind it.

The following year, the U.S. spoke in favor of exemptions to a ban. And this May, the member countries of the Stockholm Convention agreed to ban UV-328 but allowed carve-outs for replacement parts for cars and industrial machines, among other products. The U.S. ultimately supported global restrictions on the chemical, an EPA spokesperson said, noting that an updated risk assessment “included a great deal of new information” and did a “good job ensuring that the questions” were answered.

The EPA spokesperson wrote, “The Agency fundamentally rejects the premise that EPA employees are inappropriately influenced by external forces.”

Doubts About Chlorpyrifos

It was reasonable to think that the U.S. might be more supportive of a global ban on chlorpyrifos. After all, while the EPA has not banned Dechlorane plus or UV-328, it has taken a strong stand on chlorpyrifos.

The Biden administration’s decision to ban the use of chlorpyrifos on food followed a controversial about-face made by the Trump EPA in 2017. Previously, the Obama EPA had decided it could no longer vouch for the safety of the pesticide on food. Resting its case on evidence that prenatal exposure to the chemical could have lasting effects on children’s brains, the agency began the process of revoking the permission farmers need to apply it to foods they grow.

But after Trump took office, the EPA halted its plans to ban the chemical. The Trump administration hadn’t disproven the research tying chlorpyrifos to ADHD, autism, lower IQ, and memory and motor problems in children, it had ignored it. President Biden’s promise to finish the job was in keeping with his campaign pitch to follow the science.

Yet just five months after the Biden EPA proudly announced it would no longer allow chlorpyrifos to be used on food, the U.S. delegation to the Stockholm Convention joined several other countries in questioning whether the pesticide lasts long enough in the environment to merit restriction under the criteria of the convention. The member countries ultimately decided chlorpyrifos did meet their criteria, and that meeting ended with a decision to move forward.

But the U.S didn’t drop it. At the September 2022 meeting in Rome, Kovner questioned whether the levels of chlorpyrifos found in arctic regions were significant enough to harm health and the environment, thereby warranting restriction under the treaty. And this time, questions she and others raised did cause the convention to delay action.

Member countries had drafted a risk profile, which presented evidence that chlorpyrifos is transported into remote regions and accumulates in plants and animals. The paper also detailed the toxic effects that very low concentrations of the pesticide can have on dogs, birds, fish, rats and bees. The most alarming section of the report lays out the evidence that chlorpyrifos can harm children who were exposed to the pesticide in utero. Even tiny amounts of the chemical can cause neurological problems.

Kovner called the risk profile into question, according to several people at the meeting.

“Every time she had the chance, she said she had doubts” about the report, said Emily Marquez, a senior scientist with Pesticide Action Network, who was part of the convention’s working group on chlorpyrifos.

There is evidence that that chlorpyrifos has spread around the world and can now be found in caribou, ringed seals, polar bears and other animals in the arctic, as well as in the ice, seawater and air of Antarctica, and in human breast milk in numerous countries, including the U.S. It is also clearly proven that the pesticide can cause serious harm.

Kovner did not question these facts, but rather their significance, according to Watts, the New Zealand-based scientist. “She sowed doubt in the minds of all the delegates about whether the levels that are being found in the arctic actually really matter at all,” Watts said of Kovner.

In an interview, Kovner acknowledged questioning whether the persistence of the pesticide met the treaty’s requirements and noted that “about 10 other countries” in addition to the U.S. raised similar concerns.

Representatives of China and India, which are both home to companies that produce chlorpyrifos, raised questions about the report, as did an official from the pesticide industry trade group CropLife International. But according to Watts, the U.S. delegation, through Kovner, presented the ultimate obstacle to approving the report.

“The U.S. amplified this opposition from India and China,” said Watts. “And in the end, a number of countries said, ‘We’re just not sure about this.’” Ultimately, the chlorpyrifos review committee decided to defer its consideration of the risk profile, and the process of restricting or banning the pesticide was delayed by a year.

“If it hadn’t been for those actions of Karissa, it probably would have gone through,” Watts said of the risk profile. “She effectively stopped it.”

In its emailed response to ProPublica, the EPA acknowledged raising concerns about whether the levels of chlorpyrifos in the arctic are high enough to cause harm and called for further research on the risk to Indigenous people. The agency pointed specifically to a 2014 study that concluded that chlorpyrifos should not be considered a persistent organic pollutant.

That study — the only one the agency cited in its response to ProPublica — was funded by a subsidiary of Dow Chemical, which at the time was the primary seller of chlorpyrifos. A co-author of that study, Canadian researcher John Giesy, worked as a consultant to Dow on a chlorpyrifos risk assessment in the late 1990s and on Dow’s comments to the EPA about chlorpyrifos, according to Giesy’s curriculum vitae. That same CV showed that, between 1996 and 1997, Giesy also led a $1 million assessment of the ecological risks of chlorpyrifos paid for by DowElanco, which was co-owned and later bought out by Dow. (Dow subsequently merged with another company and spun off its agricultural chemicals division, and the new company stopped making chlorpyrifos in 2020.)

In its written statement, the EPA said the European Union cited the Giesy study as one of the sources it considered when drafting its proposal to restrict uses of chlorpyrifos. “We feel confident that EU carefully considered the sources of information that it provided,” the spokesperson wrote.

The EPA is embroiled in litigation over its chlorpyrifos restrictions in the U.S. In a lawsuit filed in the U.S. Court of Appeals in St. Louis, growers of sugar beets, soybeans and other crops, along with an Indian chemical company that sells the pesticide, argue that the EPA’s ban is “arbitrary and capricious.” In a court filing, the EPA denied that assertion; the agency said that the use of chlorpyrifos on food was “not safe.” Still, the farmers insist that chlorpyrifos is the only tool they have to fight certain destructive pests and say the ban will cause tens of millions of dollars of crop losses.

These are the same claims the agricultural industry made for years while the EPA was weighing the safety of chlorpyrifos. Ultimately, the evidence of the environmental and health problems caused by the pesticide won the day — at least on the home front. Internationally, the fate of chlorpyrifos remains an open question.

For her part, Kovner says the U.S. is still open to the possibility of a global ban under the Stockholm Convention. “We look forward to discussions that may provide additional characterizations or clarifications to strengthen the argument for listing chlorpyrifos under that convention,” she said.

The next meeting of the international group is scheduled for October.