This story was co-published with WTTW/Chicago PBS. ProPublica is a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for Dispatches, a newsletter that spotlights wrongdoing around the country, to receive our stories in your inbox every week.

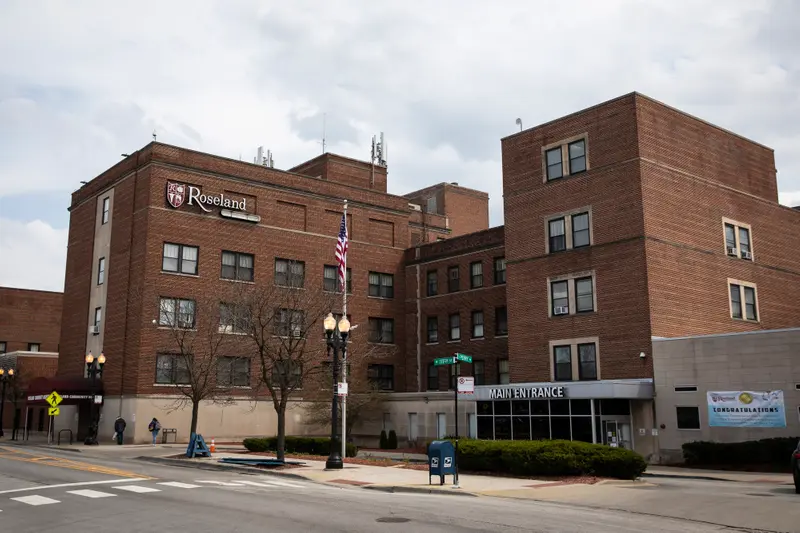

In 2013, Roseland Community Hospital was looking for a new leader. Its former chief executive had alienated the Illinois governor and other lawmakers amid a messy fight over the hospital’s funding.

The small nonprofit facility on Chicago’s South Side turned to Tim Egan, a longtime hospital executive who had begun to make a name for himself as a political operative and fundraiser with an ability to navigate the insular circles of state and local government.

Egan ran for alderman of the North Side’s 43rd Ward in 2007 and 2011, and he has served as the leader of the Cook County Democratic Party’s 2nd Ward committee since 2016, during his time as head of the hospital.

In his close to nine years as Roseland’s president and chief executive, Egan’s political activities and the hospital’s operations have become increasingly entwined: hospital business awarded to friends and associates, employees and contractors making donations to Egan’s campaign funds, at least one fundraiser using the hospital’s name on invitations.

In the runup to the November elections, Egan appeared in a commercial for Illinois Comptroller Susana Mendoza’s reelection campaign that, according to experts in nonprofit governance, blurred the lines even further between Egan’s stewardship of Roseland and his efforts in state and local politics.

“Susana is a giant for saving the New Roseland Community Hospital,” Egan declared in the commercial for Mendoza, a Democrat and longtime ally who last month won a second full term. As the state’s chief financial officer, Mendoza pays the state’s bills, including reimbursing hospitals like Roseland for patients on Medicare and Medicaid.

Egan this year also co-hosted a Mendoza fundraiser at which tickets cost as much as $5,000.

Samuel Brunson, a professor and associate dean at Loyola University Chicago, said Egan’s appearance in the commercial crossed a line. IRS rules bar nonprofits from participating in political campaigns.

“That looks to me like a pretty flagrant violation of this rule,” said Brunson, who specializes in nonprofits and the tax code and viewed the Mendoza commercial at the request of WTTW/Chicago PBS and ProPublica.

In the commercial, Egan is identified as Roseland’s president and CEO and stands in what appears to be a hospital setting in front of two people dressed in lab coats.

“It’s not him saying the hospital endorses her, but it’s him saying, ‘I am the CEO of the hospital, I’m speaking in my capacity as CEO … about what she did for the hospital itself,’” Brunson said.

A spokesperson for Egan and the hospital said in a statement that Egan’s political work is not a secret to Roseland’s leadership, and it has only helped the hospital achieve its goals in the community. The spokesperson did not address the question of whether Egan’s appearance violated federal nonprofit rules.

“Mr. Egan has an excellent relationship with his board and keeps board members fully apprised of all of Roseland’s major contracts and business developments, often times to seek their advice and approval,” said the spokesperson, Dennis Culloton. “Similarly, the board members are updated on his efforts to establish strong government contacts to support the mission of Roseland Community Hospital.”

Rupert Evans, a health care consultant and the chair of Roseland’s board of directors, said in a statement that Egan has done a “tremendous job” in his role leading Roseland and that the hospital board is “fully aware” of his political activities.

“None of his activities outside of his primary duties cause any conflict of interest for the hospital and have been fully disclosed,” said Evans, a former chair of the health administration program at Governors State University.

The most serious penalty for violating rules barring political activity by nonprofits is termination of an organization’s nonprofit status — though that sanction is rarely levied for this kind of activity.

The Treasury Department, which oversees the IRS, declined to comment on the commercial.

A spokesperson for the Mendoza campaign said the commercial refers to the comptroller’s work getting Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements to cash-strapped hospitals, including to Roseland.

“Roseland Hospital plays a critical role in providing healthcare to the underserved communities on Chicago’s South Side, so we asked Tim Egan to attest to the Comptroller’s work in our video spot which ran this fall,” campaign manager Jack Londrigan said in a statement. “We would have never asked Tim to do anything we thought would pose a problem for him or the hospital as we believe his efforts to save and protect the lives of Roseland residents are of the utmost importance.”

Longtime hospital consultant James Orlikoff, a Chicago-based adviser on governance and leadership issues for the American Hospital Association, said Egan’s appearance in the campaign commercial “probably pushed the boundary, if not crossed it.” But he also says given the “unprecedented financial pressure” hospitals are facing, having an experienced political operator at the helm could be beneficial.

Egan’s appearance in the commercial follows a trying period for Roseland. ProPublica and WTTW/Chicago PBS reported in October that federal inspectors found that, since January 2020, errors or neglect had contributed to the deaths of at least seven Roseland patients, including one who was pregnant.

Those incidents prompted federal watchdogs to admonish the hospital and threaten sanctions unless the facility took corrective measures. Federal records indicate that Roseland leaders fixed those immediate safety violations. A spokesperson for the hospital and a top official there have said that the COVID-19 pandemic contributed to many of Roseland’s challenges.

A 2021 federal whistleblower lawsuit alleges other problems at Roseland. Unsealed this month in federal district court in Chicago, the complaint claims that Roseland was complicit in a scheme by a physician who worked at the hospital to bill for millions of dollars in unnecessary or fraudulent COVID-19-related medical care.

Culloton, the spokesperson for Roseland and Egan, said neither Egan nor the hospital had been involved in any improper conduct. The lawsuit is pending.

The campaign commercial for Mendoza wasn’t the first time Egan has used his position as part of Mendoza’s campaign. An invitation to a $250-to-$5,000-a-ticket fundraiser in May at the swanky 95th-floor Signature Room of what was once the John Hancock Center was billed as an opportunity to join “Roseland Community Hospital President Tim Egan for a healthcare heroes reception in support of Susana Mendoza.”

“That looks a whole lot like an endorsement, and it looks like an impermissible endorsement,” Brunson said.

Neither Culloton nor Mendoza’s campaign responded to questions about the campaign event.

For a hospital executive like Egan, such a move into politics may have pitfalls, especially if their preferred candidate loses an election. “Now,” said Brunson, “they’re on the outs with whoever got the office.”

The board has signed off on at least one move Egan has made that tied the hospital to a friend and political associate. In October 2020, the board’s executive committee voted unanimously to transfer the management of Roseland’s emergency department from the medical group that had long held the contract to a wholly owned subsidiary company.

That December, that subsidiary of Roseland signed a three-year, $10,000-a-month consulting contract with P2C Healthcare Consulting, a company that had registered with the state just a month earlier. P2C’s manager, Leonard Cannata, has no apparent experience in health care management.

Cannata is a lawyer and political consultant who has worked for at least one of Egan’s political campaigns. Several photos posted to the Roseland CEO’s personal social media accounts show the two smiling as Cannata displays holiday gifts given by Egan. In a 2011 endorsement of Cannata’s skills on LinkedIn, Egan described him as a “detail oriented and determined” professional. “Len is destined to succeed in life,” he added.

Egan’s spokesperson didn’t answer questions about the political relationship between Cannata and Egan, but said the contract with P2C “significantly lowered the costs to Roseland, including lower insurance costs. This arrangement was arrived at in collaboration with and with the approval of the Roseland Community Hospital Board.”

P2C, according to its contract, is charged with physician recruitment, performance metrics, and business plan implementation. In an internal hospital email obtained by WTTW/Chicago PBS and ProPublica, a hospital executive said P2C was the management group for the emergency department.

Cannata did not respond to requests for comment. Evans, the board chair, did not respond to questions about the contract.

In another instance, Roseland signed a contract with the company American Medical Lab to run the hospital’s in-house lab for five years at an annual cost of $1.5 million. That deal was signed in February 2021. That fall, the company donated $5,000 to one of Egan’s political funds.

The president of the lab company did not respond to a request for comment.

Culloton also did not respond to questions about the American Medical Lab contract.

Roseland serves a majority-Black community on Chicago’s far South Side that has long faced segregation and disinvestment. According to the hospital, 86% of the people living in its service area are Black. In 2020, nearly 92% of the people receiving care at the hospital relied on Medicare or Medicaid.

But on at least two occasions during the fall of 2020, while the hospital provided on-site coronavirus testing, it also offered clinics in mostly white Chicago neighborhoods where residents had average incomes far higher than those of the residents that Roseland is supposed to serve. In September and December of 2020, Roseland offered COVID-19 testing in the North Side’s 2nd Ward, where Egan works as the Democratic committeeperson. One of the testing events was held in the city’s upscale Gold Coast neighborhood. It’s not clear how many such events Roseland provided.

The Roseland and Egan spokesperson said the testing clinics served a need in the community.

“Roseland Community Hospital,” the spokesperson said in the statement, “makes no apologies for its effort to assist the City of Chicago Department of Public Health and other public health authorities in making COVID-19 testing available to as many people as possible.”

Meanwhile, Egan’s political activities have received contributions from people and businesses associated with both Roseland and his former employer Norwegian American Hospital, which is now known as Humboldt Park Health.

Between Egan’s first run for alderman in 2007 and this year, political funds that he chairs have received nearly $100,000 in donations, loans and in-kind contributions from hospital staff and leadership, board members for both hospitals and their respective charitable foundations, and people and businesses who have done work for the hospitals.

Among those donors is Dr. Tunji Ladipo, former director of Roseland’s emergency department. Ladipo, who was listed as a member of Roseland’s board of directors in its most recent available tax filing, donated $14,000 to Egan’s political committees between 2016 and July 2022.

Ladipo did not respond to requests for comment.

Enrique Lopez, another of Egan’s donors and political allies, has prepared hospital tax returns and has audited its financial statements. Lopez and his accounting firm have given more than $7,000 in donations and in-kind contributions to Egan’s various political funds; Lopez is treasurer of one of those funds.

Angel Chatterton, a senior accounting instructor at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, said those kinds of political and financial ties could make outside observers question whether the audits conducted by Lopez’s firm were swayed by “undue influence” from hospital leadership.

“Auditors not only need to be objective, they need to be perceived as objective as well,” Chatterton said. “That’s at the heart of the credibility of our profession.”

She added that while the arrangement may be entirely aboveboard, “when you’re dealing with any type of political situation like this, I would say additional safeguards need to be put into play.”

Culloton, the Egan spokesperson, defended the use of Lopez’s firm, saying the firm was brought in after the hospital had not performed an audit or filed some key documents for close to 20 years.

Egan “is grateful for the excellent work of the hospital’s auditor Mr. Enrique Lopez who holds his firm up to the highest standards of professionalism,” Culloton said. “Mr. Egan complies with Roseland Community Hospital Board policies and procedures including those addressing disclosure and potential conflicts of interest.”

Lopez did not respond to a request for comment.