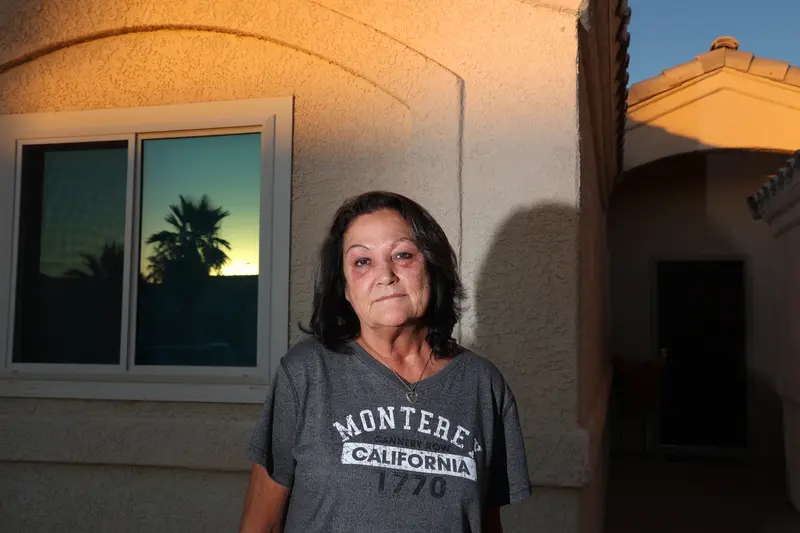

In the year since her husband died, Royanne McNair felt increasingly lonely in North Las Vegas. With most of her children and grandchildren in the Midwest, she decided to sell the house she and her husband had already paid off and move back to Ohio.

Her goal was to be there by July 29, the anniversary of her husband’s death.

Eager to find a buyer for the well-maintained, four-bedroom stucco house, she called a local HomeVestors of America franchise.

“I got a letter through the mail. That’s why I called them,” McNair, 69, said of the company known for its “We Buy Ugly Houses” slogan. “I just thought it would be easier for me to sell that way, not realizing how much money I would lose.”

A representative from the franchise, Black Rock Real Estate, came to her house and offered $270,000 on the spot. She signed a contract that evening.

But when McNair called one of her sons to share the news, he was dismayed. A quick internet search showed she could get much more for her home. So three days after signing the contract, she reached out to the company and said she wanted to cancel it.

The Black Rock representative countered by offering to raise the sales price by $14,000 — which McNair considered and even verbally agreed to, before calling again and asking to be let out of the deal. She said she didn’t hear back from the company after that.

An investigation by ProPublica this year found that HomeVestors franchises sometimes deploy aggressive tactics to bind homeowners to sales contracts, even when they no longer want to sell their homes, including filing lawsuits and recording documents on the property’s title. In response to ProPublica’s findings, HomeVestors prohibited its franchisees from clouding titles by recording documents to make it nearly impossible to sell to anyone else and cautioned that filing lawsuits to enforce a sales contract should only be done in rare circumstances.

Black Rock Real Estate — established in 2012 by Carl Bassett, a former appraiser — is among the most successful of HomeVestors’ 1,150 franchises. In 2021, it generated the company’s third-highest sales volume and won “Franchise of the Year.” Bassett, who has been recognized as one of the company’s “top closers,” also helps recruit and train new franchise owners.

McNair, believing she was free of her contract with Black Rock, listed her house with a real estate agent and within days received nearly 20 offers. She accepted one for $372,500 — more than $100,000 over Black Rock’s offer.

McNair was ecstatic. The new deal was set to close July 14. A search for lawsuits, liens and other obligations against the title that would prohibit the sale came back clear. She was on her way to getting to Ohio by the end of the month.

Then an envelope appeared at the office that was handling the sale’s escrow process. Inside was a copy of the Black Rock contract that McNair thought had been canceled. Its arrival immediately halted the sale.

In Nevada, and more than half of U.S. states, escrow offices, rather than lawyers, handle the process between the signing of a contract to sell a house and the deal closing. Escrow officers are neutral third parties who facilitate real estate transactions by ensuring no one else has a claim to the property and holding funds as the deal is executed. The escrow officer was duty-bound to freeze the process until a resolution was found for the competing contract to buy McNair’s home.

McNair was forced to hire a lawyer.

The escrow officer told McNair’s real estate agent, Ryan Grauberger, that the FedEx envelope had arrived without a name or return address, something Grauberger said he hadn’t seen in 24 years in the business. Neither had the escrow officer, he said.

“It’s a very dirty tactic,” Grauberger said.

After ProPublica contacted Bassett about McNair’s experience with Black Rock, he called her and promised to release her from the contract. He also offered to pay her legal expenses.

“Oh, he was so apologetic,” McNair said.

Among the reasons HomeVestors’ leadership gave for banning its franchises from clouding sellers’ titles and filing lawsuits excessively is that such practices create a public records trail that reporters and prosecutors can trace.

In McNair’s case, there was no public record trail to show who had sent the Black Rock contract to her escrow officer. In a brief phone conversation with ProPublica, however, Bassett acknowledged that his office did so. It did it because the escrow officer had refused to discuss the deal, noting that Black Rock wasn’t a party to the sale, he said.

“We believed we still had a contract with Ms. McNair,” Bassett said. “It had nothing to do with blocking the sale or trying to hurt her.”

Bassett said he never received the text message or the email McNair sent formally requesting to cancel the contract. He said Black Rock’s title company had reached out to her multiple times attempting to close the sale. (McNair said she was never contacted by Bassett’s title company.) Bassett said he learned of her desire to exit their deal when a ProPublica reporter emailed him.

“When we did get the opportunity, we did the right thing,” he said, chalking it up to a “misunderstanding.”

McNair provided copies to ProPublica of the text message and email she sent to Black Rock to cancel the contract. Unbeknownst to her, she had misspelled the recipient’s name on the email. The text message was sent to the office phone number, which Bassett said doesn’t receive text messages.

Asked about this transaction, a spokesperson for HomeVestors corporate office said: “Our priority was to make sure that the seller’s concerns were addressed and to ensure the seller is satisfied with the outcome of this process. We believe the franchisee achieved this by canceling the previously signed contract for the house. The other aspects of the transaction will be reviewed by HomeVestors.”

Steve Silva, a Nevada real estate lawyer since 2013, said he also has never heard of a contract appearing anonymously during escrow. The typical way of staking a claim to a property is a lawsuit demanding the seller be held to the contract, he said. That’s the type of action HomeVestors has told its franchises to take only rarely.

“Especially in light of the directive to not use the old tactic, it could be he was looking for a new way to try to find some pressure to get his agreement through,” Silva said.

Simply mailing a contract to an escrow officer could be a “risky move,” he added. Depending on how enforceable the contract is, such a tactic could open up a person to claims of interfering in a business deal or slandering title by making a false claim to the property, he said.

In McNair’s case, Grauberger said Black Rock did start an escrow process but never paid the $1,000 good-faith deposit required by the contract. “In my mind, it’s a dead contract,” he said.

Bassett declined to comment on why his company never made the deposit.

On July 14, McNair closed on the sale of her home arranged by her real estate agent and is on schedule to move to Ohio by the end of the month. “I’m exhilarated,” she said.

Bassett made good on his offer to pay McNair’s legal fees.

“I got a $600 check on my table,” she said.

But he also made another request. He told McNair that the Black Rock representative — a parent of five children — who got her to sign the contract could lose his job if ProPublica publishes a story about it. He asked McNair if he could record a statement from her and take her photograph. She said he wanted to publish his own story to “retract” what ProPublica reports. (Bassett said this is an inaccurate description of his conversation with McNair but declined to detail what he told her.)

“I’m not going to do it,” McNair said. “I don’t want to bother with HomeVestors any more.”

Byard Duncan contributed reporting. Mollie Simon contributed research.