U.S. Army soldiers accused of sexual assault are less than half as likely to be detained ahead of trial than those accused of offenses like drug use and distribution, disobeying an officer or burglary, according to a first-of-its-kind analysis by ProPublica and The Texas Tribune.

The news organizations obtained data from the Army on nearly 8,400 courts-martial cases over the past decade under the Freedom of Information Act and analyzed a process known as pretrial confinement. The resulting investigation of the nation’s largest military branch revealed a system that treats soldiers unevenly and draws little outside scrutiny.

What is pretrial confinement?

When service members are accused of crimes, their commanders, who aren’t required to be trained lawyers, get to decide whether they are detained before they go to trial.

Here are the main findings from the investigation:

1. Soldiers accused of sexual assault are placed in pretrial confinement at lower rates than those charged with some more minor offenses.

On average, soldiers had to face at least eight counts of sexual offenses before they were placed in pretrial confinement as often as those who were charged with drug or burglary crimes, the news organizations found.

That disparity has grown in the past five years. The rate of pretrial confinement more than doubled in cases involving drug offenses, larceny and disobeying a superior commissioned officer, but it remained roughly the same for sexual assault, according to the analysis.

“Justice that’s arbitrary is not justice,” said Col. Don Christensen, a former chief prosecutor for the Air Force. “It shouldn’t come down to the whims of a particular commander.”

2. Use of pretrial confinement varies from one Army post to another.

As a whole, the Army has used pretrial confinement in about 1 in every 10 cases handled by the branch’s highest trial courts over the last decade, but some posts employ it at a significantly lower rate than others, the news organizations found. For example, at Fort Bliss in El Paso, Texas, defendants were confined ahead of trial 5% of the time in cases involving sexual assaults, while soldiers at another large Texas installation, Fort Hood, were confined almost 12% of the time in the same type of cases.

3. Across the Army, soldiers charged with drug crimes are confined at an especially high rate.

More than 1 in 6 Army drug cases that went to courts-martial in the past decade involved a defendant who was put in pretrial confinement, twice the rate of sexual offense cases. Aniela Szymanski, a private attorney and U.S. Marine Corps Reserve judge advocate, said commanders often interpret drug use as jeopardizing the morale or safety of the unit, whereas they tend to view sexual assaults as a conflict between two people.

“I think that’s going to take some time for commanders to grow into having the same knee-jerk reaction to sexual assault offenses as they do to drug offenses,” she said.

4. The Army’s justice process is different from the civilian one.

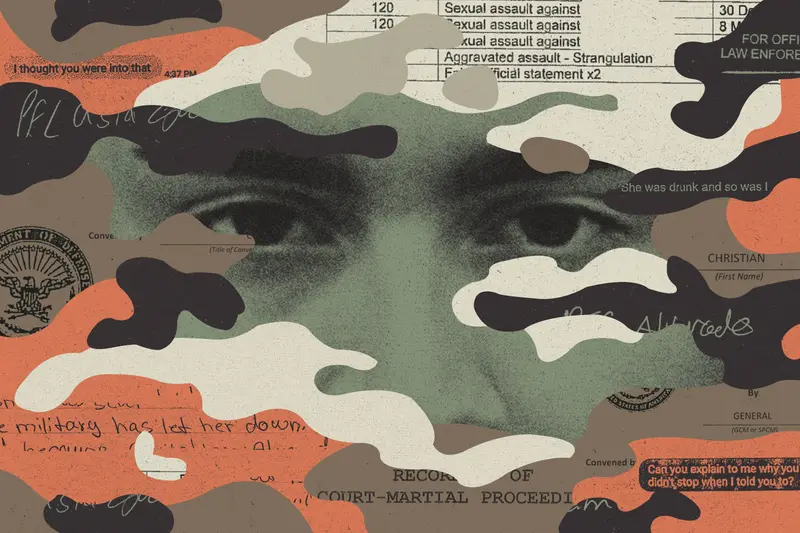

Take the case of Christian Alvarado, an Army private first class at Fort Bliss who admitted in a sworn statement to sexually assaulting a fellow soldier in December 2019.

“She was drunk and so was I,” Alvarado wrote in July 2020. “We had sex, but she passed out.”

On the same day, Alvarado acknowledged that he had sex with another woman while she was intoxicated, which he said was wrong. He would not agree to a sworn statement about the second allegation because he said he believed it would just be “icing on the cake.”

At the end of the interrogation, Alvarado’s commanders didn’t place him in detention or under any restrictions beyond the orders he had already received to stay at least 100 feet away from the two women who had accused him of assault, according to records.

A month later, Alvarado assaulted another woman.

Had Alvarado’s case been handled by civilians and not the military, his written admission could have been enough evidence to quickly issue an arrest warrant and bring a criminal charge, according to two lawyers who previously worked for the El Paso County district attorney’s office.

“I would have felt comfortable charging at that point,” said Penny Hamilton, who led the Rape and Child Abuse Unit at the district attorney’s office and later served as an El Paso County magistrate judge.

In Texas’ civilian system, Alvarado would have then gone before a magistrate judge, who could set a bail amount in the tens of thousands of dollars. He’d only be released if he could pay the bond.

The military justice system has no bail. Many decisions about who should be detained for serious crimes before trial are made not by judges but by commanders, who are not required to be trained lawyers.

The Army eventually charged Alvarado with the three sexual assaults in late October 2020 and ordered him to stay 100 feet away from the third woman to accuse him. Still, he was not detained.

Lt. Col. Allie Scott, a former Fort Bliss spokesperson, said that the conditions to justify placing Alvarado in pretrial confinement were not met after the three assault accusations. She declined to answer additional questions seeking clarification, saying Fort Bliss would not comment on internal deliberations.

In June 2021, a military judge found Alvarado guilty of sexually assaulting two women, strangling one of them and lying to investigators. He was sentenced to 18 years and 3 months in a military prison and a dishonorable discharge. His case is under appeal.

Alvarado told the newsrooms he was innocent but declined to answer specific questions.

5. Despite calls for reforms, commanders still control many parts of the military justice system.

Congress passed reforms last year that stripped commanders of some of their powers related to certain serious crimes. The law created a new office of military attorneys, giving them, and not commanders, the power to prosecute cases such as sexual assault, domestic violence, murder and kidnapping.

But commanders retained prosecutorial control over other offenses. They also still control who is placed in pretrial confinement in all cases, serious and minor.

Army officials defended the system. They said that soldiers accused of violent offenses aren’t necessarily more likely to get pretrial confinement. “The nature of the offense is one factor to consider in a decision to put someone in pretrial confinement, but it is not the sole factor,” said Lt. Col. Brian K. Carr, chief of the operations branch at the Office of the Judge Advocate General’s Criminal Law Division, in an email. Characteristics of individual soldiers and their willingness to follow orders are also important factors, Carr said.

He said that, under military regulations, commanders must first decide whether there’s good reason to believe that a soldier committed a crime and is either likely to flee before trial or engage in serious criminal misconduct. Commanders have to consider if other restrictions, such as directing soldiers to remain in military housing or requiring regular check-ins with superiors, are sufficient to keep them out of trouble. They should also weigh a soldier’s military service record, character, mental condition and any previous misconduct.