Corey Winfield was 10 when he saw someone get shot for the first time. He and a friend were marching around with a drum in the Park Heights section of Northwest Baltimore, and a few older guys asked if they could use it; while they were doing so, someone came up and shot one of them in the back, paralyzing him. At 11, Corey found his first gun, in an alley near his school. He sold it to a friend’s older brother for $45 and used the money to buy lots of penny candy. At 13, he saw someone get killed for the first time — a friend, who was 14 — and that year he started selling drugs. After he was robbed a few times, he bought another gun. When he was 17, he was buying some drugs to sell when the dealers tried to rob him, so he shot one of them, killing him.

Winfield went to prison for nearly 20 years. Two weeks after his release, in 2006, his younger brother, Jujuan, who was 21, was shot to death outside the family’s house. For days, Winfield stalked the man he suspected of the murder; he might have killed him, but a police cruiser appeared as he was about to shoot. He went home, where he found his aunt Ruth, who had brought him up, sitting alone in the dark. She told him that she knew what he was up to. “Please stop, I don’t want to lose another baby,” she said to him. “I broke down and we cried on the sofa,” Winfield told me.

Winfield promised to give up guns, and soon he committed to getting others to stop shooting, too. Baltimore was building a “violence interrupter” program, modeled on one launched in Chicago, in which people who have criminal records and a history of street violence use their contacts and credibility to defuse tensions before anyone is shot. Winfield became one of the first outreach workers in the new program, Safe Streets, citing his willingness to eschew vengeance as proof that peace was possible. Jujuan’s death “opened my eyes up to the pain I was causing and had been causing for half my life,” he told me. “I was part of the mayhem and the destruction.” Soon after he joined, he helped a 19-year-old who wanted to stop selling drugs procure a copy of his birth certificate, so that he could get regular work. When the young man finally got the document, he started crying. “All my life, they told me my father didn’t know who I was,” he said. “But he signed my birth certificate, and that’s gotta mean he loved me.”

Many other cities also began adopting the interrupter model. It had intuitive appeal as a complement to policing: why not deploy people with neighborhood know-how and the motivation to redeem themselves? “There’s so many things that we could do and should be doing, outside of law enforcement, before things get to the point of needing to utilize the criminal justice system,” Monique Williams, a public health researcher who until recently led Louisville, Kentucky’s Office for Safe and Healthy Neighborhoods, said.

There was resistance from police departments: The interrupters generally avoided cooperating with the cops, and some officers were wary of men whom they had arrested not so long ago. Some interrupters lapsed into drug dealing or other illegal activity. In Louisville, the Metro Council stopped funding the city’s three interrupter teams in 2019 after an interrupter was arrested for dealing methamphetamine (the charges were later dropped) and another worker was charged with raping a woman. (He was convicted of a related felony.) “There was not a lot of believing in the product from the Metro Council,” the leader of one team, Eddie Woods, told me. “So any excuse is a good excuse to pull the plug on it.”

In 2020, everything changed. Violence spiked across the country, with homicides rising by 30%, wiping out two decades of progress. Criminologists attributed the rise to a combination of the social disruption caused by the pandemic and the deterioration of police-community relations after the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, which led to less proactive policing and less cooperation from residents. After the presidential election, Joe Biden’s administration looked for ways to stem the violence without relying solely on traditional law enforcement, which had come under intense scrutiny on the left. In 2021, Congress passed the American Rescue Plan Act, or ARPA, which included funding that many cities are spending on “community violence intervention,” the catchall term for non-police approaches to reducing violent crime. In addition to interrupters, these measures include programs that detach young men from gangs, those which meet with shooting victims in hospitals to deter retaliation and those which offer young men employment and counseling in cognitive-behavioral therapy.

For years, these programs competed with one another for whatever scarce funding was available, passing from one short-lived pilot project to another. Now they are being showered with unprecedented resources: Louisville is getting $24 million; Baltimore will receive $50 million.

The funding has created an opportunity for community violence intervention to become a significant feature of the public safety landscape. But the challenges are still immense. The programs have only a few years to prove that they deserve lasting support after the federal money runs out. Public safety agencies that until recently consisted of a handful of people are having to expand rapidly to oversee millions in spending, building a new civic infrastructure in a matter of months. And the evidence for how well some of the programs work is mixed and sometimes elusive, not least because it’s hard to measure crimes that never happen. “The money creates a problem,” Eddie Woods said. “Everybody’s an intervention specialist now.”

Gary Slutkin, an epidemiologist, spent seven years in the late 1980s and early ’90s at the World Health Organization, working to contain the HIV-AIDS epidemic in Central and East Africa. He had previously fought cholera in Somalia and a tuberculosis outbreak in San Francisco. When he returned to the United States in 1995, he went to Chicago to be near his parents. Deciding which cause to take on next, he settled on one of the leading drivers of mortality in the city: violence.

Chicago had about 900 homicides per year, and Slutkin found the debates about causes and solutions deeply unsatisfying. “I just began to ask people what they were doing about it, and nothing made sense to me,” he said. “It made no scientific sense. It had no logic. There was no theory other than ‘bad people.’” As he saw it, gun violence was an epidemic not unlike the diseases he had spent his career fighting. “It qualifies as a contagious disease, as it has characteristic signs and symptoms causing morbidity and mortality, and it’s contagious, as one event leads to another,” he told me.

Slutkin believed that it needed to be treated as an epidemic by using public health workers to reach those who were most infectious and susceptible. Those workers should be people who “have credibility and access to the population that you need to talk to,” he said. In Chicago, that entailed recruiting men with criminal histories to serve as outreach workers in neighborhoods experiencing high rates of violence.

In 2000, with the University of Illinois Chicago as his institutional base and initial funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, Slutkin deployed a team of eight workers in West Garfield Park, one of the most violent neighborhoods in the city. Shootings there declined by 68%. Slutkin added teams in six more areas in the next couple of years, and within a year shootings in those areas decreased an average of 30%.

It was an impressive result, but homicide rates were falling all over the country, and other models of violence reduction were also seeing success. One was the “focused deterrence” model, pioneered by David Kennedy in Boston, which included group interventions, wherein teams of prosecutors, police officers and respected community figures met with young men deemed most likely to commit violent crimes and offered them social services, coupled with the threat of consequences if they engaged in further violence.

But Slutkin’s model — eventually called Cure Violence — got enough credit for reduced shootings that other cities began deploying interrupters, often hiring Cure Violence to train and guide them. Many city governments were leery of hiring people with serious criminal records, and the programs were often run by nonprofit groups that had looser restrictions.

When Baltimore launched Safe Streets, in 2007, its homicide rate was among the highest in the country. Dante Barksdale, a charismatic native of East Baltimore in his early 30s, helped lead the effort almost from the start. “I was tired of getting locked up, of getting robbed by police, of having to keep an eye out at all times,” Barksdale later wrote of his attraction to the program. “I wanted a regular job. And it seemed the universe had one in mind for me. My reputation as a hustler would help the Safe Streets mission, more than any amount of training could.”

Safe Streets put its first team in McElderry Park, on the east side. Barksdale, who was better known by his nickname, Tater, became a champion for the program as it expanded into three more neighborhoods in the next few years, a period during which homicides began falling sharply in Baltimore for the first time in decades. He joined Cure Violence staff from Chicago for training sessions around the country. Cobe Williams, Cure Violence’s training director, would drive around the Chicago housing projects with Barksdale. “That’s my guy,” Williams told people. “He is so committed to stopping the violence.”

Like many interrupters, Corey Winfield found it hard to avoid sliding back into illegal activity. By 2011, he was selling drugs on the side to supplement his Safe Streets wage, $13 an hour, with which he was supporting two daughters. His aunt Ruth chided him. Winfield told me, “She said: ‘Listen, you’re doing God’s work. You can’t do God’s work and still do the Devil’s work. God’s going to punish you.’” Two months later, he was arrested after giving a ride to a friend who was on the way to a robbery and sentenced to five years’ probation.

Winfield found it challenging to strike the balance demanded of a “credible messenger” — using the reputation gained from past brushes with the law to earn the trust of those who were still entrenched in the streets while avoiding such behavior himself. Sometimes, he told me, he was ostracized by friends who saw him wearing an orange Safe Streets T-shirt. “When I first put this shirt on, the whole city knew, and it was hard, but I didn’t take it off,” he said. “I would go up, like, ‘Yo, what’s up,’ and you walk away. I’m usually in, but now you all walk away, you leave. It’s hard on me.”

Winfield left the program for a few years and worked with an organization that served runaway youths. Then, in April 2015, a 25-year-old man from West Baltimore named Freddie Gray died from injuries sustained while in police custody. Protests and rioting ensued, and gun violence in the city increased dramatically. The circumstances foreshadowed those in 2020: a surge in homicides that followed a death at police hands and a collapse in police-community trust, which led to changes in police behavior, and calls for non-police approaches to public safety. Amid the spike in violence, Corey Winfield decided to rejoin Safe Streets.

In his absence, Safe Streets had continued to struggle with the problem of workers falling back into crime: A site in West Baltimore had been suspended in 2013 after two of its workers were arrested, and in July 2015, an East Baltimore office closed after police found drugs and seven guns there and arrested two workers. But the program retained enough support that, in 2018, the mayor at the time, Catherine Pugh, who had moved control of the program from the Health Department to City Hall’s public safety office, expanded it from four sites to 10.

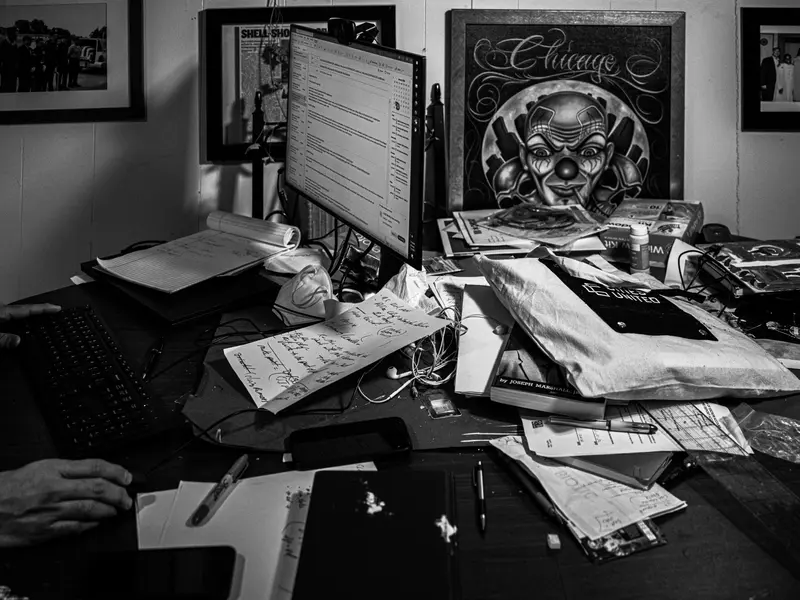

On Martin Luther King Jr. Day in 2018, I was in an East Baltimore church as Winfield told an audience drawn from several local congregations how violence interruption worked. Big Corey, as he is known, is 6 feet, 3 inches tall and weighs 280 pounds, and his size is matched by a bright-eyed, magnetic charm. He sketched out a typical scenario: “Anita calls me and says: ‘Corey, my brother, I heard him talking, and they’re going to kill Lisa’s brother. Him and his buddies. ’Cause Lisa’s brother gets out of work at 3 in the morning and they’re going to get him.’ So I say, ‘OK,’ so I’m gonna get up at 2:30 and I’m gonna be out there so that when Anita’s brother jumps out on Lisa’s brother they’re going to see me. ‘Oh, it’s 3 in the morning. We ain’t doing this, right?’”

Winfield continued, “Now, we know for a fact that 3 o’clock in the morning the police ain’t around. The police don’t mean a damn thing when somebody is coming to get killed. But somebody coming with guns, if they see me, that level of respect is high.

“But once that respect leaves,” he added, alluding to his perceived independence from the police, “I’ll be lying beside Lisa’s brother. We cannot lose that, because that’s all we have. That makes us, the effectiveness we have.”

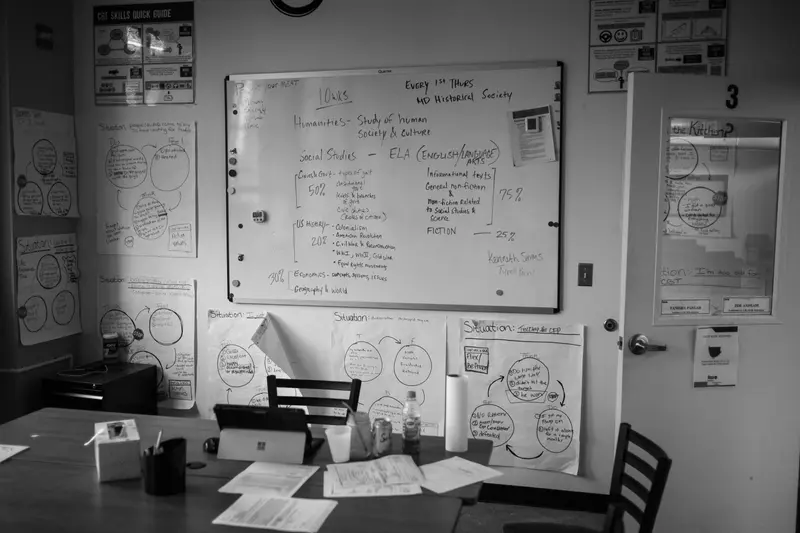

That year, a different model of community violence intervention was emerging. In Massachusetts, an organization called Roca, which had worked for years with high-risk young adults in gritty places like Chelsea, Lynn and Springfield, was trying a new approach, using behavioral-theory techniques to help participants control their emotions.

The approach tapped into a new neuroscientific understanding of how trauma and harsh circumstances can keep people operating in survival mode — in their “bottom brain.” Roca believed that participants needed to acquire basic emotional self-regulation before they could advance to job training and other forms of support. “What we know changes behavior is people feeling safe, being able to manage their emotions and begin to heal their trauma,” Molly Baldwin, Roca’s founder, said. Instead of mediating conflicts, as Cure Violence does, Roca was seeking to make young people less likely to be drawn into conflict in the first place.

The approach gained traction in Chicago, under the leadership of Eddie Bocanegra. Like Corey Winfield, Bocanegra had committed a murder; in 1994, at the age of 18, he had avenged the shooting of two members of a gang he belonged to. He served nearly 15 years in prison; after his release, he joined Cure Violence. In 2011, he was among a handful of workers featured in “The Interrupters,” a documentary film about the organization. Bocanegra, a slightly built man with a goatee, stands out in the film for his soft-spoken, cerebral bearing. One scene shows him doing good deeds, like delivering flowers, on the anniversary of the murder he’d committed. “I’ve thought of hopefully one day going to my victim’s family and really just expressing to them how deeply sorry I am,” he says. “It’s just that, right now, I don’t think it’s still right.”

Soon after the documentary was released, Bocanegra quit Cure Violence. He was becoming increasingly aware of what the focus on intervention was leaving out. “How can I expect someone to put their guns down when their basic needs aren’t being addressed?” he said to me.

He became an organizer with the Community Renewal Society, a social justice organization, while pursuing a master’s degree in social work at the University of Chicago. By 2013, the YMCA of Metro Chicago had hired him as its co-director of youth safety and violence prevention, working with some 400 teenagers, many of whom were involved in gangs. It was fulfilling work, but he was disturbed by the contrast between the investment that was made in the teenagers and the paltry efforts made on their behalf after they turned 18.

Homicide rates remained well below their historic highs in Chicago, as they did nationally — in 2015, the city registered only 468 murders. But, late that year, the city released a video of a police officer firing 16 shots at Laquan McDonald, a 17-year-old armed with a knife, killing him. As in previous episodes of excessive police force, in Ferguson, Missouri, and Baltimore, the video gave rise to protests, an erosion of police-community trust and a sharp rise in deadly violence. In 2016, there were 764 homicides in Chicago.

The city’s civic and business leaders committed $75 million for violence-prevention efforts. Much of the funding went to a new initiative called READI Chicago, which took a different approach from that of Cure Violence. READI identified several hundred men, mostly in their 20s, who were recruited by outreach workers and referrals upon release from incarceration. The men had, on average, between four and five felony arrests each, and 80% of them had been the victims of violence. The program provided them with 12 months of paid job training and employment plus cognitive-behavioral techniques. It was, by the standards of violence-prevention programs, an expensive undertaking — eventually, $25,000 per participant.

Eight years after Eddie Bocanegra completed his prison sentence for first-degree murder, he was chosen to lead the initiative.

In Baltimore, the expansion of Safe Streets faced challenges. The city had to find nonprofit organizations to manage the sites and people to staff them. Cure Violence had stopped leading training sessions some years earlier, after the city grew lax about paying its bills. Meanwhile, the leadership of City Hall’s public safety office changed four times between 2017 and 2020.

Amid the disorder, several Safe Streets staff members left for jobs at a new anti-violence effort in the city: Roca. In 2018, the Massachusetts organization had opened a branch in Baltimore, the hometown of its leader, Molly Baldwin. Instead of targeting certain areas — even after its expansion, Safe Streets still covered only 2.6 of the city’s 92 square miles — Roca focussed on some of the hardest-to-reach young men between the ages of 16 and 24, drawn from across the city. They were generally referred to Roca by the police or by juvenile services; Roca came into contact with some through making regular visits to the homes of victims of nonfatal shootings. Within several years, the organization was working with about 200 young men — applying cognitive-behavioral theory, putting some on job crews and simply maintaining contact with them through the organization’s practice of “relentless outreach.” “It’s the more long-term approach, the more meaningful, sustained behavior change that we’re looking for,” James “J.T.” Timpson, who left Safe Streets to join Roca in 2018, said. “While I believe that the intervention is extremely important, even intervention requires some type of follow-up. You can intervene today, but what happens tomorrow?”

In late December 2020, Baltimore’s new mayor, Brandon Scott, named as director of the public safety office his longtime friend Shantay Jackson, a former information technology manager who had embraced anti-violence activism after Freddie Gray’s death and after her stepson was gravely injured in a 2018 shooting. She had led a nonprofit group that got the contract to oversee one of the new Safe Streets sites — a site that then experienced serious troubles despite being in the least dangerous of the 10 locations. It shut down only a few months after opening, in 2019, a closure that Jackson attributed to concerns about the safety of the workers. (It was later reopened.)

A month after Jackson took over the public safety office, Dante Barksdale, the champion of Safe Streets, was paying a visit to the Douglass Homes, a public housing project in East Baltimore, on a Sunday morning. A gunman shot him in the head and body nine times, killing him.

Even in a city that had experienced more than 300 homicides for six years in a row, the killing of the admired leader of the best-known violence-prevention program — its “heart and soul,” according to Scott — was a big blow. “My heart is broken with the loss of my friend Dante Barksdale, a beloved leader in our community who committed his life to saving lives in Baltimore,” Scott said.

Six months later, another Safe Streets worker, Kenyell “Benny” Wilson, was shot in the South Baltimore neighborhood of Cherry Hill while driving to lunch and died after making his way to the hospital. Two people familiar with the case told me that Wilson, who was 44, had reprimanded a teenager for being rude to an elderly woman, and his colleagues suspected that this had prompted the shooting. “Tonight, our brother Kenyell Wilson became a victim of the gun violence he worked every day to prevent,” Scott said.

Six months after that, in January 2022, DaShawn McGrier, a newly hired Safe Streets worker in McElderry Park, the program’s first site, was on duty just after 7 p.m., standing with several other men, when a gunman drove up and started shooting, killing McGrier, who was 29, and two others and injuring a fourth man. Scott called the shooting a “horrific tragedy.”

Three deaths, in 13 months, in a program with fewer than 100 workers. It was exactly the dark scenario that Corey Winfield had sketched out four years earlier: The orange T-shirt no longer provided enough protection.

At what point did a program’s administrators need to decide that the work was simply too dangerous? “Three people lost their lives,” Joseph Richardson Jr., a University of Maryland ethnographer specializing in gun violence, said. “That’s not normal. To have three Safe Streets workers killed, we need to assess what’s going on.”

Roca underscored the safety of its workers, who were paid at least $60,000 a year, compared with the $45,000 that Safe Streets workers typically make. Roca was cautious about sending its staffers into areas when tensions were high, and, unlike Safe Streets, it maintained direct lines of communication with the police. “Are we really supposed to send another human being, not the police department, no equipment, in this day and age, when people are loaded up with automatic weapons?” Baldwin said. “To assume someone is going to listen to someone is to assume that they can access the thinking part of their brain.”

Slutkin, the founder of Cure Violence, defended his approach. If violence interruption went awry, as it had in Baltimore, that was a sign that an individual program wasn’t following the model correctly, he said. “The difference is always whether they’re really doing it,” he went on. “Let’s say, in any given city, there’s three places that are getting results and four aren’t getting results. You can’t just keep not getting results for the whole year.” There are protocols for running an interrupter site, he said — from hiring the right people to reaching the right people on the street and keeping close track of outcomes.

Slutkin, who stepped down as the head of Cure Violence last year, referred to positive results in other cities, including Chicago and Philadelphia. But some experts have interpreted the results in these cities, and in others, as being more mixed. Jeff Butts, a sociologist at John Jay College who led a study in New York, told me that interrupter programs are fundamentally difficult to assess — it’s hard to know whether a decline in shootings in an area is due to the interrupters or to all the other factors at play. The assessments typically tally only the shootings within the narrow boundaries of interrupter zones, even though the interrupters’ work inevitably ranges farther afield.

Further complicating the research is that the approach varies so much from one site to another. “They live under the same banner, the same T-shirts, the same brand name, the same philosophy,” Butts said. “But they all insist on doing things their own way.”

To better gauge interrupters’ effectiveness, researchers at Johns Hopkins University and the University of Maryland were in talks with Baltimore’s public safety office last year to conduct a comprehensive study of Safe Streets that would include field observations and interviews with workers and participants for nine months. But the qualitative component of the study fell through after city officials, citing costs, insisted that it run for fewer months. Richardson, of the University of Maryland, who would have led the field work, said that he plans to do a similar study in Washington, D.C., instead. “You can have all the numbers in the world,” he said, “but if you don’t understand how it plays out on the ground, without having that context you can’t really capture the effectiveness of the program.”

Programs such as Roca and READI Chicago are easier to assess because they work with a defined group of men whose outcomes can be tracked. A randomized controlled study of READI Chicago released last year found that men who had participated in its 18-month program were nearly two-thirds less likely to be arrested for a shooting and nearly one-fifth less likely to be shot than men with similar backgrounds who had not been offered a place.

Cure Violence leaders were quick to put READI Chicago’s results into context. Such programs help those who are fortunate enough to be enrolled, but what about all the other young men in the neighborhood? “You have programs like READI that maybe get 50 or 100 guys, and that’s what they’re working with,” Charlie Ransford, Cure Violence’s director of science and policy, said. “But what if some guys get released from prison and they’re not with them? What if a group of kids a few blocks over start getting into stuff and they’re not helping them? We’re community-based, they’re looking at individuals. We’re looking at the mass on a daily basis.” Helping some young men get on track was essential, he said, but insufficient. “You need Cure Violence as the head of the spear.”

Last winter, the competition suddenly took on broader ramifications. The Biden administration created a position within the Department of Justice to oversee the distribution of $250 million for community-violence-intervention efforts, part of legislation passed in response to the mass shootings in Uvalde, Texas and Buffalo, New York. Three decades after Eddie Bocanegra’s murder conviction, and a decade after he left Cure Violence in search of a different approach, he was tasked with helping lead the federal government’s response to the biggest surge of violence since the early-’90s wave that he had been part of.

Many cities are using some of their new funding to start or expand teams founded on the Cure Violence model, among them Atlanta; Charlotte, North Carolina; Columbus, Ohio; Memphis, Tennessee; Philadelphia; St. Louis; Peoria, Illinois; Winston-Salem, North Carolina; Nashville, Tennessee; and Wichita, Kansas.

In Louisville, the launch of five new Cure Violence teams is being led by a city agency that did not exist until less than a decade ago. After a high-profile triple homicide in 2012, Mayor Greg Fischer created the Office for Safe and Healthy Neighborhoods, which started out as essentially a one-man shop run by Anthony Smith, a community organizer. It now has 50 employees. Unlike many of its counterparts in other cities, in recent years the agency has been led by people with deep expertise in violence prevention: Monique Williams, who stepped down in October, is a public health researcher, and her successor, Paul Callanan, has worked as a probation officer and later led a gang-reduction initiative in Denver.

In collaboration with city and community leaders, they came up with a plan for the $15 million the office was getting, which included hiring case managers and funding two hospital-visitation programs and three of the five new interrupter teams. Separately, the city launched an effort based on David Kennedy’s focused deterrence, which, unlike Cure Violence, includes a major role for police and prosecutors.

Louisville was adopting a hybrid approach, bringing together focused deterrence, interrupters and long-term case management into a single ecosystem for violence reduction. Compared with Baltimore, where the city’s public safety office has presided over a falloff in cooperation between Safe Streets and Roca, Louisville has maintained a unified, citywide approach, with biweekly meetings to discuss specific incidents and individuals.

The sense of urgency is high in Louisville, where homicides nearly doubled in 2020, to 173, the most ever recorded. But Callanan told me that he is wary of the demand for quick action, fretting that federal deadlines for spending ARPA money — it must be committed by the end of 2024 — wouldn’t give cities time to build intervention efforts strong enough to justify continued local or state taxpayer support once the federal funding runs out in 2026. “We’re laying this expectation across the country that you can take a Cure Violence program and you can get it up and running in three months and you’re going to have these dramatic results,” he said. “The reality, historically, is it takes a long time to build these programs.”

The interrupter model, Callanan noted, had been created during the Chicago gang wars of the ’90s, before large gangs fractured into smaller crews and before social media upended communication. “We have the challenge today of taking these concepts and putting them into play in our communities where the dynamics have completely changed,” he told me.

This meant rethinking the profile of the ideal violence interrupter. Perhaps, he said, it was no longer necessarily the forty- or fiftysomething former gang member — “OG” — who would have commanded respect a couple of decades ago. Now, with social media, youths could find notoriety much more quickly. “You may have a 22-year-old with more clout than the 40-year-old guy who started a gang there,” Callanan said. “You may be hiring individuals based on a gang background or a historical background that is no longer relevant today to the groups that you’re dealing with.”

“It’s not about gang warfare anymore,” a former administrator of Safe Streets told me. “The problem is more impulsive crazy shit.” At a YMCA in Louisville, I met Demetrius McDowell, who had been hired by a new interrupter site in the Smoketown neighborhood run by the nonprofit group YouthBuild. McDowell had spent years selling heroin before shifting his focus to real estate, which drug proceeds had helped him accumulate, and to efforts to help boys and young men stay off the path he had taken.

Despite his age — 43 — McDowell was attuned to the swirl of online antagonism in the city. He described one of the most prevalent forms of social media provocation: Someone would livestream a video of himself supposedly on rival territory, and a rival would challenge him to reveal his location — to “drop a pin” — or otherwise be deemed a coward. “If you’re not tracking these things on their social network, you’ll never know what’s going on in the street,” McDowell told me. “That’s where I get all my information.”

McDowell lasted less than two months on the YouthBuild team. He clashed with its leaders over a wish to continue building his own youth group, which had a contract with the YMCA. He also bristled at the adherence to protocols that Cure Violence trainers and one of the team’s supervisors, a college graduate, demanded. “You need individuals who can relate to the community,” he said, “but you got college guys coming in telling you how he thinks you should do it. A college fellow is telling me that you ought to do it this way because studies say this or that. It has to be a feel thing. ... This educated guy has no type of experience. I’ll take experience over data anywhere that could be manipulated.”

With the new funding came expectations that the programs institute standardized training, conform to established guidelines and collect copious data. But some of the interrupters viewed these demands as top-down cluelessness that undermined the organic nature of their work.

“We’ve had a couple that didn’t work out,” Lynn Rippy, YouthBuild’s director, said. “We got them in for a little bit and realized that, in terms of the intake of information and the way we want to do business, that wasn’t going to work for them. So it didn’t work for us.”

Last September, Eddie Bocanegra came to Baltimore to announce the distribution of the first $100 million of the Department of Justice funds he oversees. He made the announcement not at City Hall or at Safe Streets but at Roca, which was receiving $2 million. Of some 50 other recipients nationwide, relatively few were interrupter programs.

A month later, Bocanegra was back in the city for the annual conference of Cities United, a national violence-prevention network founded in 2011 by, among others, the former Philadelphia Mayor Michael Nutter and the former New Orleans Mayor Mitch Landrieu and now led by Anthony Smith, the first director of Louisville’s public safety office. The two-day event drew hundreds of people from around the country, an indication that, thanks to the surge in federal funding, community violence intervention was experiencing a moment of arrival.

But, in a closed-door session with mayors and other top city officials, Bocanegra offered a cautionary note. The field, he said, “is so grossly underdeveloped. We continue to use two or three models from the 1990s and early 2000s. This field has evolved, social media and technology have evolved, gangs have evolved. There are pockets of promising evidence and good models, but, because of a lack of investment, we’re not seeing that return. If this was a board of directors running a Fortune 500 company, we’d ask ourselves some very serious questions about our investment.” There was an unjust element to the pressure to produce results: police departments had, after all, received exponentially more resources for decades, even as violence remained high in many cities. “There’s a lot of pressure to hurry up and reduce the violence,” Shani Buggs, an assistant professor of public health at UC Davis who briefly worked for the Baltimore city government, said. Community violence intervention, she told me, “should be seen as a core city function, as police are seen as a core city function. There’s never a question about whether they should get rid of the police department because violence hasn’t gone down.”

In Bocanegra’s remarks, he stressed that the field wasn’t doing enough to develop the workforce tasked with the actual intervention. Workers were not getting adequate support for the frequent traumas of the job and rarely gained the skills to advance from street work. “We’ve overlooked so much talent and potential,” he said. “We’re not building the field.”

The “credible messenger” approach meant shifting enormous emotional and physical risk onto people who had already been through a tremendous amount. The messengers were, in a sense, both the best and the worst people to do interrupter work. To address these concerns, some cities, including Baltimore, allocated part of their ARPA funds to provide counseling for their interrupters. Shantay Jackson, the head of Baltimore’s public safety office, said that the workers “are dealing with their own level of trauma, given their lived experiences, but also dealing with vicarious trauma as they do the work of interrupting violence every single day.”

In Baltimore, the new funding was increasing the pressure. “We need to learn as much as we can from the things that we’re rolling out, because in a couple of years we won’t have $50 million to throw at the problem,” Councilman Mark Conway, the chairman of the public safety committee, told me. “And when we make a decision about where we pare back, we’re going to need to look back at our data, we’re going to need to look back at our systems, and make some tough decisions about where we get the best bang for the buck.” Facing demands from the City Council to show how the public safety office was spending the money, Jackson released a breakdown — some was being given to nonprofit groups, some to the city’s launch of a focused-deterrence initiative and some to new staff positions, expanding the office from 15 to about 40.

At the same time, the public safety office was losing two of its main liaisons to Safe Streets, raising the risk of further drift. And, as reported by the Baltimore Banner, the office was delaying Roca’s contract to deliver services to young men involved in the focused-deterrence initiative. The effort to build a unified violence-reduction ecosystem was foundering on turf battles and personal conflicts, though Jackson downplayed the tensions, saying that her office and Roca “continue to have conversations that I think have been very productive.”

One evening in early December, I was on my way to meet Corey Winfield when he told me that he would have to postpone: in the Baltimore neighborhood of Brooklyn, where he was now the Safe Streets site director, a gang member had stolen a car from a member of another gang, and Winfield and his team were trying to get the car returned before anyone tried to avenge the theft.

It had been a tumultuous stretch for the Brooklyn site, which, like several others in the city, was now administered by Catholic Charities. In November, a former worker at the site had pleaded guilty to dealing fentanyl while he was employed by Safe Streets. The site, which was supposed to have seven workers, had only five. But Winfield was pleased about the progress of an interrupter he had recruited for another site, a 38-year-old man he had met in prison who had survived three shootings. Winfield also took pride in the food distribution that his site had undertaken during the pandemic and in his idea to begin distributing used purses and handbags filled with hygiene products to the many sex workers in the area.

A week later, I stopped by the Brooklyn Safe Streets office to see Winfield, but it appeared to be closed. I called him, and he told me that his aunt Ruth had just died of cancer. I went to the wake, at a church in West Baltimore, where I found Winfield in the lobby, being consoled by several Safe Streets workers wearing orange sweatshirts.

He told me that he had been there for an hour and a half and hadn’t been able to go in to see her. “I can face a firing squad and my heart will still be strong,” he said. “But I’ve not been in there yet. It’s the hardest thing I’ve ever had to do.”

He also told me about another recent intervention. Three months earlier, a sex video involving high school students had surfaced online, angering a rival group of teenagers, who had beat up one participant, stealing his designer bag and sunglasses, then fired shots at a car belonging to another participant’s mother.

This was not in Winfield’s Safe Streets zone, but he went to help. He reached out to the mother of a member of the retaliating group, fearing that she might be a target, and, for several days, he accompanied her on the bus to work. “It’s how kids think now,” he said. “If they can’t get who they’re targeting, they’re going to get you.”

He also reached out to the father of one of the students in the video; the man was known to Winfield as a “shot caller,” someone who had the ability to arrange a killing or to defuse a conflict, and he had been making provocative comments about the episode online. At a 2 a.m. meeting on an abandoned block, arranged by the superiors in the crew that the father belonged to, Winfield urged him to de-escalate. “We were able to resolve it. That’s what we do out here,” Winfield said. “We squashed it. But nobody knows about those kinds of stories.”

Two weeks after the wake, a couple of miles west of the church, five high school students were shot outside a Popeyes across from their school at lunch. One of them, a 16-year-old, died. For Roca’s staff, it was a delicate situation — the murder victim was the younger brother of a Roca participant, and Roca leaders wanted to proceed strategically with their outreach to the other victims. Corey Winfield, in contrast, wanted to get involved immediately. He knew that retaliation was likely, and he wanted Safe Streets on the scene, figuring out who might seek vengeance. But the shooting was several miles from his site.

Winfield called me to voice his frustration. “We need to get on top of that now,” he said. “This is the real shit, right here. This needs to be handled right now. We don’t have a week or two. More kids are going to die.