Understanding the contracting chain on cell tower jobs can be complicated, but crucial when workers die.

William “Bubba” Cotton, 43, was the first of 11 cell site workers who died on AT&T projects from 2006 through 2008, years when the carrier merged its network with Cingular and ramped up its 3G network for the iPhone.

As ProPublica and PBS “Frontline” reported last month, tower climbing ranks among the most dangerous jobs in America, having a death rate roughly 10 times that of construction.

The project Cotton was on involved several layers of subcontractors, which is common in the tower industry. The accident was more unusual. Most of the 50 tower climbers killed on cell site jobs since 2003 have died in falls, but Cotton was crushed to death by an antenna.

A wrongful death lawsuit subsequently filed by Cotton’s survivors, as well as a personal injury suit filed by his cousin and co-worker, Charles “Randy” Wheeler, explored two questions at the heart of every tower fatality: Who controlled the tower site? And who was responsible for the safety of the subcontractors working on it?

Here’s a breakdown of what happened in the Cotton case:

The Project: An upgrade of a cell site in Talladega, Ala., replacing the antennas on a 400-foot tower. AT&T had designated the upgrade a top priority because of an upcoming NASCAR race, a company manager said in court testimony.

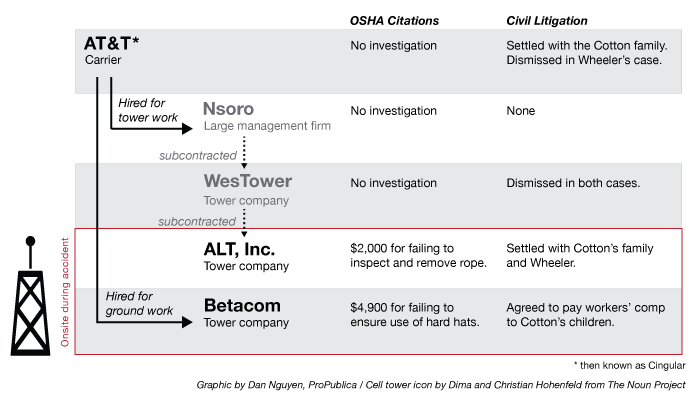

The Subcontractors: To handle the tower work, AT&T (then known as Cingular) hired Nsoro, a large management firm (also known as a “turf vendor.”) Nsoro hired a subcontractor, WesTower Communications, a large North American tower company. WesTower subcontracted the on-site work to a Missouri-based tower company, ALT Inc.

AT&T also directly hired Florida-based subcontractor Betacom Inc. to work on a concrete equipment shelter at the base of the tower.

The Accident: On Friday, March 10, 2006, around noon, the ALT crew, led by foreman Josh Cook, was lowering an antenna from the tower, while the Betacom crew, which included Cotton and Wheeler, worked inside the shelter.

As Cotton, Wheeler and two co-workers exited the shelter for lunch, the rope ALT was using snapped. The 50-pound antenna plummeted more than 200 feet to the ground, killing Cotton.

Two of Cotton’s co-workers ran off to the nearby woods and vomited. Wheeler cradled Cotton’s head with his t-shirt and prayed, waiting for emergency responders to arrive.

The Investigation: The Occupational Safety and Health Administration, which regulates worker safety, opened investigations into ALT and Betacom after Cotton died.

ALT was cited for failing to inspect and remove the rope that snapped and fined $2,000. Betacom was cited for failing to ensure that workers on the ground crew wore hard hats and fined $4,900. OSHA sent letters to both companies saying it was dangerous for tower crews to work above other crews, and that even though regulations did not forbid it, they should avoid such situations.

The agency did not open investigations into any of the other companies in the contracting chain, even though Cook told an OSHA inspector that he had felt unsafe working above other contractors on site and had asked for a deadline extension so that he would not have to do so. (In an interview in March with ProPublica and PBS “Frontline,” Cook said he was not concerned about Betacom workerson the day of the accident because they were working inside the concrete shelter and not out in the open.)

Damon Depew, a project manager working for AT&T agreed with Cook and later gave sworn testimony that he had asked Terry Newberry, then an AT&T implementation manager, for more time. Depew said Newberry denied the request. Newberry testified that he did not recall the conversation.

According to a sworn deposition, an AT&T safety manager initiated an internal investigation after the accident, but stopped “once he found out that it wasn’t an (sic) Cingular employee” that had died.

The Litigation: Cotton’s two daughters, both minors, filed a wrongful death lawsuit in Talladega County Circuit Court in March 2006 against AT&T and Betacom. They later amended the suit to include ALT, WesTower and the owner of the tower, Crown Castle, as defendants. The case was subsequently moved to U.S. District Court of Alabama.

Wheeler, who claimed he suffered a back injury diving to avoid the falling antenna, filed a personal injury lawsuit against AT&T, ALT,WesTower and Crown Castle in U.S. District Court of Alabama in October 2006.

Lawyers for the Cotton family and Wheeler argued that all of the defendants should share some responsibility for the accident. As the operator of the cell site, they said, AT&T had a legal duty to ensure the workplace was safe that day, they claimed.

The plaintiffs also argued that AT&T had created a work environment where “time and money took precedence over safety” and had repeatedly pressured subcontractors to meet an “unreasonably dangerous schedule.” Further, the plaintiffs alleged, the carrier had insisted that the tower crew replace antennas at the same time that it should have known Cotton and Wheeler were working on the ground. AT&T employees had regularly visited the site but had failed to establish any coordination procedure to prevent the two subcontractors from endangering each other, lawyers for the plaintiffs said.

AT&T argued that it should be dismissed as a defendant from both cases and said it had no duty to Cotton or Wheeler, who were independent contractors, not employees.

Though AT&T acknowledged it had set the project’s specifications and deadlines, it said it had not controlled how contractors performed their work – specifically, it did not tell ALT how to lower the antenna and did not tell Betacom when to break for lunch. AT&T also argued that Betacom’s work on the day of the accident was not inherently dangerous and “if Cotton or Wheeler had taken the slightest care in the performance of their duties, they would have been able to cross the tower premises safely.”

The carrier also claimed that the multi-employer doctrine, an OSHA policy that extends liability to companies who supervise subcontractors at a jobsite, had been abandoned by the agency and was never recognized in the Eleventh Circuit, the jurisdiction where this case was being heard.

The Outcome: In August 2008, AT&T entered into a confidential settlement with the Cotton family without admitting wrongdoing. AT&T’s “potential exposure in this wrongful death case is significantly higher” than the amount of the settlement, the judge noted in approving the deal.

A judge dismissed AT&T as a defendant in the Wheeler case in October 2008, concluding Wheeler had not proved that AT&T controlled the subcontractors’ work on the day of the accident or that the carrier knew ALT’s crew would be working over Betacom’s that day.

After Wheeler appealed, AT&T filed a notice of intent to seek costs from him, estimating it had spent more than $14,000 on the case. In February 2009, Wheeler dropped his appeal and AT&T dropped its claim for reimbursement.

ALT settled with Cotton’s children and Wheeler in November 2008 for undisclosed amounts. Betacom agreed to pay workers’ compensation in the Cotton case, splitting the payments between Cotton’s daughters. WesTower and Crown Castle were dismissed as defendants in both cases.

AT&T declined to comment on the Cotton case, referring ProPublica and PBS “Frontline” to a written statement it provided about issues related to tower work. So far, Nsoro, WesTower, ALT and Betacom have not responded to requests for comment related to this story.

Mapping the Contracting Chain

The AT&T cell tower job in which William Cotton died involved several layers of subcontractors. This chart shows which companies in the contracting chain were investigated by OSHA and the results of litigation by Cotton’s family and his co-worker, Charles Wheeler.