This article was produced for ProPublica’s Local Reporting Network in partnership with Anchorage Daily News. Sign up for Dispatches to get stories like this one as soon as they are published.

Alaska Gov. Mike Dunleavy said Tuesday that state law enforcement agencies had failed to collect the DNA of more than 21,000 people arrested for a variety of crimes, a task officials were required to perform under Alaska law.

The Anchorage Daily News and ProPublica reported in December that some law enforcement agencies were not aware of the law or were not following it. As a result, authorities neglected to collect DNA swabs that might have solved cold cases and put serial offenders behind bars.

The governor vowed that police, Alaska State Troopers and corrections officials would follow the law going forward and would try to track down the missing DNA.

The Department of Public Safety estimates that Alaska authorities have failed to collect DNA from about 1 in 4 qualifying arrests and convictions since 1995. The lapse violated a state law passed with fanfare in 2007 that aimed to put Alaska at the country’s leading edge for solving rape cases.

Since May, the Dunleavy administration has rejected a series of Daily News and ProPublica public records requests for information on the backlog; the governor’s office first made the numbers available in a news conference Tuesday.

Of the 21,577 people whose DNA should have been collected, 1,555 are now dead, according to an accompanying report by the Department of Public Safety. A statement from the governor’s office said Dunleavy has now directed the department to collect DNA from the remaining 20,022 people.

Alaska is now one of at least 31 states that require DNA samples to be collected when a person is arrested or when certain criminal charges are filed against them. The swabs are meant to be sent to the state crime lab, where the DNA would be extracted and could be matched against evidence from cold cases and kept on file to aid in future cases.

The evidence could be used to solve not only sexual assault cases, but also homicides, burglaries and other crimes, and could even exonerate the wrongly convicted.

But as recently as December, the Daily News and ProPublica found, some Alaska police departments were unaware of the law or had only recently started collecting the required DNA samples.

The failure was perhaps most striking in the case of accused serial rapist Alphonso Mosley, whose DNA was not submitted to the state crime lab following a qualifying arrest in 2012. In the years that followed, prosecutors say, Mosley committed three more rapes across the city, impregnating one of his victims. Even when he was arrested a second time for domestic violence in 2015, no DNA was collected, contrary to state law.

The news organizations filed a public records request on May 20 asking for any preliminary estimate of the number of missing or owed DNA samples and for the names of those from whom the state had not yet collected a DNA sample.

The state Department of Public Safety denied that request and a subsequent attempt to appeal, and also denied a request for copies of meeting notes from a state working group that discussed the issue.

On Tuesday, Deputy Attorney General John Skidmore said the state didn’t release the numbers earlier because the data was spread across various law enforcement software systems. “We had to do searches in each system and try and reconcile the reports that came out of each system to make sure we had a clear understanding of what those numbers were.”

A Dunleavy spokesperson said the effort to determine the number of missing samples began in December 2019 and involved the departments of public safety, law and corrections. Skidmore said the Department of Law would continue to withhold the identities of people whom law enforcement had failed to swab for DNA.

Asked if the state anticipates legal action by victims of offenders who might have been in jail had their DNA been collected as required by state law, Skidmore said, “No.”

Other states are also finding that their DNA collection laws have been ignored or partially implemented.

Researchers in Ohio were among the first to quantify the problem, reporting in 2019 that about 15,300 DNA samples had been missed in Cuyahoga County. The Tennessee Bureau of Investigation estimates that more than 76,000 DNA profiles from felony offenders are missing in that state, based on preliminary research.

The attorney general’s office in Washington state, Alaska’s nearest neighbor, calculates that “tens of thousands” of people legally owe the state DNA samples for entry into the FBI’s Combined DNA Index System (CODIS).

As for collecting the missing Alaska samples, Skidmore said state law allows for someone convicted of certain crimes to be charged with a new felony if they refuse to provide DNA, which may provide a tool for tracking down the missing samples. (Under state law, someone who is swabbed for DNA at the time of their arrest but is ultimately not found guilty of the crime can ask to have their sample removed from the system, he said.)

The Department of Corrections will be “the primary point of contact” for DNA collection, Dunleavy spokesperson Corey Young wrote in an email Tuesday. In addition to obtaining samples from people who are currently incarcerated, probation and patrol officers will assist in the collection of samples from people who are on supervised release, while booking procedures will ensure that a sample is taken whenever someone is taken into custody for a qualifying crime, he wrote. In addition, people who are on the Alaska sex offender registry and still owe a DNA sample will be swabbed when they first register or renew their registration.

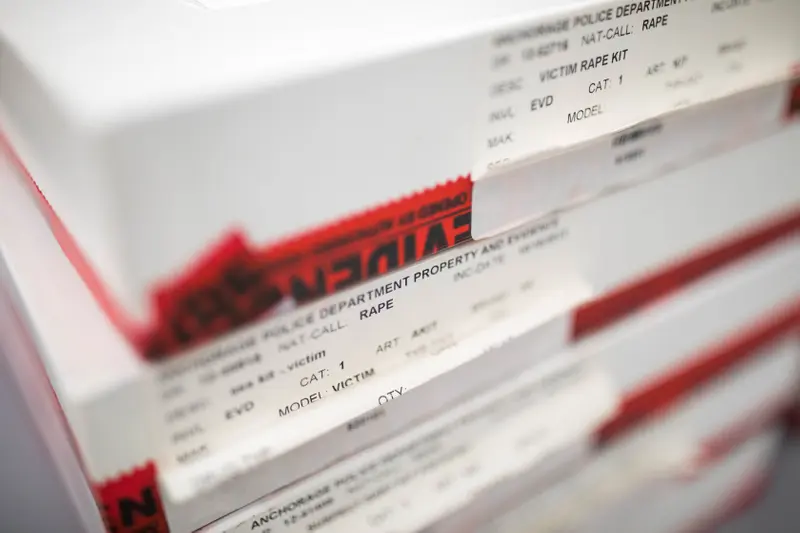

The thousands of missing DNA samples might help explain why the effort to test a backlog of unexamined rape kits has yielded only one new prosecution.

Alaska Public Safety Commissioner James Cockrell called the collection effort a top priority for his department. People who owe a DNA swab to the state will be contacted through the Department of Corrections if possible, he said, or local and state law enforcement may work together to locate them and collect a sample.

“Our No. 1 priority will be for violent offenders and sex offenders,” he said.