With the seal of Santa Barbara Countyâs district attorney on its cover, the envelope caught Jennifer Osbornâs attention immediately. And when she opened it, Osborn read something startling: She was being accused of a crime.

With the seal of Santa Barbara Countyâs district attorney on its cover, the envelope caught Jennifer Osbornâs attention immediately. And when she opened it, Osborn read something startling: She was being accused of a crime.

Osborn, the letter alleged, had "violated criminal statutes by issuing a bad check." She faced as much as a year in jail and a $2,500 fine unless she made good, paid an additional $215 in fees and spent a Saturday at a "financial accountability class."

The letter stunned the 20-year-old college sophomore. Osborn was unaware that a $92 check sheâd written to her school bookstore had bounced, the result of a mix-up with her mom, she said. "Failure to pay in full and schedule class within TEN DAYS from the date of this Notice may result in your case being forwarded for criminal prosecution," the letter threatened.

Alarmed, Osborn signed up for the class. But there were some things she didnât know at the time.

Despite the official seal, the letter wasnât sent by the DAâs office. Osborn had no obligation to attend a class to avoid prosecution. And there was virtually no chance sheâd be charged with a crime â in fact, the DAâs explicit policy was not to consider prosecution for bounced checks under $100.

Osborn is among the approximately 2 million people a year who receive similar letters (PDF) from American Corrective Counseling Services, a privately held firm that has turned bad checks into a thriving business. The California-based company has deals to run "diversion" programs on behalf of some 150 county DAs. In return, the DA offices get a cut of the fees.

The companyâs contracts are careful to note that ACCS is working in a supporting role only. Though it operates under a local DAâs "name, authority and control," contracts say, the prosecutorâs office "does not delegate to ACCS any aspect of the exercise of prosecutorial discretion." But that legal nuance is lost in the sternly-worded form letters the company issues to people like Osborn.

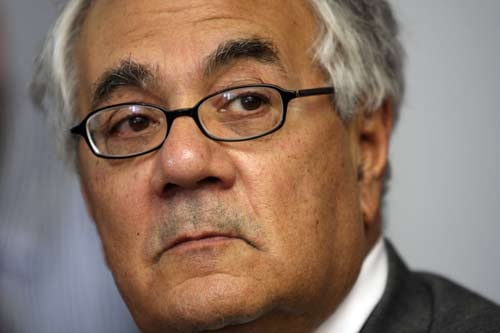

The firmâs methods have drawn the ire of consumer advocates and class action attorneys who say prosecutors and ACCS are not enforcing criminal law, as they contend, but cashing in by using deceptive debt collection practices. After federal lawsuits were filed in several states, lobbyists for ACCS and district attorneys turned to Congress. They persuaded Rep. Barney Frank, D-Mass., to offer critical support for an amendment exempting the program from the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, and thus legitimized ACCSâs practices.

The firmâs methods have drawn the ire of consumer advocates and class action attorneys who say prosecutors and ACCS are not enforcing criminal law, as they contend, but cashing in by using deceptive debt collection practices. After federal lawsuits were filed in several states, lobbyists for ACCS and district attorneys turned to Congress. They persuaded Rep. Barney Frank, D-Mass., to offer critical support for an amendment exempting the program from the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act, and thus legitimized ACCSâs practices.

The exemption went through in 2006 without a public hearing. Frank, now chairman of the House Financial Services Committee, said he went along after being told the program was a path for participants to avoid a criminal charge.

But thatâs not always true.

ProPublica obtained ACCS contracts (PDF) under open records laws and found that DAs who contract with ACCS are asked to specify a minimum check amount subject to prosecution review. The DAs allow ACCS to send threatening letters to thousands who, like Osborn, wrote checks under the limits.

Budget data from a dozen of the biggest counties that use ACCS show that DA offices have cashed in. Over the past four years, Los Angeles County received $1 million. In Illinois, Cook County collected more than $160,000 over a 12-month period. Floridaâs Miami-Dade County raked in $375,000 between April 2005 and September 2008 (see list).

"They are renting the prosecutorâs seal, and they are using that name and authority to collect bad check debt," says Deepak Gupta, director of the Consumer Justice Project at Public Citizen, a consumer advocacy group that joined much of the litigation against ACCS.

ACCS gets the lionâs share of the proceeds. Although the firmâs financials are private, court records show that revenues are enough to cover a staff of nearly 300 and make payments on $32 million in debt to a private-equity firm that is helping bankroll the company.

Michael Schreck, chief executive officer of ACCS, declined comment. He referred questions to prosecutors and one of the companyâs attorneys, Charles Jenkins, who said accusations of deception have no merit. "We have to stop making it harder for the district attorneys to get their job done," Jenkins said. "How abusive could a program be if a district attorney is the source of the problem?"

Prosecutors call the ACCS program a win-win. Like traffic school, it allows them to divert defendants away from court into educational classes after a finding of probable cause that they have committed a criminal act. Merchants get repaid about a third of the time; DAs free up resources to handle serious crimes and get a modest budget boost.

"This particular function is one that we can legally outsource to a company experienced in doing this," said Sharon Matsumoto, an assistant district attorney in Los Angeles County. "With all the violent crime in Los Angeles County, we have to concentrate on our core mission."

But Osborn said prosecutors also have an obligation to be upfront. It wasnât until she sat through the five-hour class and paid the extra fees that she realized the local DA wasnât directly involved. "I was upset and angry at first," she said, "but in hindsight, I am disappointedâmostly because the district attorney takes an oath to abide by our laws."

But Osborn said prosecutors also have an obligation to be upfront. It wasnât until she sat through the five-hour class and paid the extra fees that she realized the local DA wasnât directly involved. "I was upset and angry at first," she said, "but in hindsight, I am disappointedâmostly because the district attorney takes an oath to abide by our laws."

California started for-profit route

Bounced checks were a national scourge in the mid-1980s, when ACCS was born and the notion took hold of creating a diversion program. Debit cards have since slowed the problem since, but U.S. banks still process billions of checks annually. In 2006, the most recent year available, 153 million bounced â less than 1 percent. By comparison, 240 million checks bounced in 2000.

"There was a tremendous problem with insufficient funds in our community," said Grover Trask, a former district attorney in Riverside County, Calif., who pioneered the diversion concept. "We decided the best way to solve the problem was to create a low-level program to handle these crimes."

In 1985, the California Legislature passed what Trask said was the first bill legalizing such programs. Most district attorneys ran them in-house, using their own staff to determine probable cause that a crime was committed and initiate cases. But one part of the legislation allowed prosecutors to privatize the operation. Trask ran his Riverside County program internally for several years until it strained resources. By 1993, he decided to contract out the program and turned to ACCS.

The company was founded in 1987 by Don Mealing. A Nevadan whoâs called himself a "serial entrepreneur," Mealing and a partner launched the business by writing a series of counseling intervention curricula for different offenses â petty theft, assault and battery and domestic violence. Municipal courts in Nevada adopted the programs, Mealing said, and the business quickly spread to Northern California, where in 1988 the first bad check program began in Merced County.

"I was really the first one in the country to figure out how to engineer this for district attorneys to make it work," said Mealing, who sold most of his interest in the business in 2004.

Mealing said ACCS was bringing in $18 million a year at the time and has since grown. Court records (PDF) show that he and his partners were paid more than $25 million. The company, headquartered in San Clemente, Calif., is now primarily owned by a partnership that includes Schreck and other ACCS executives. As a private corporation, it is not required to report its revenue, but a court filing says ACCS has 292 employees and a $500,000 monthly payroll.

Today, an estimated 200 of the nationâs more than 3,000 counties have bad check programs. About 150 outsource the operation to ACCS, which in court papers said it sends out 200,000 "repayment proposal lettersââ a month on behalf of district attorneys.

ProPublica obtained ACCS contracts with 15 counties through public records requests. Typical terms (PDF) allow ACCS to collect fees that can far exceed the value of the check that bounced.

A $10 restitution charge goes to the merchant. ACCS typically charges a class fee of $150 to $165, a $10 convenience fee if clients opt for a payment plan, a $25 rescheduling fee if someone misses class, and an administrative fee of $35 to $50. The latter fee is typically split 50-50 with prosecutorsâ offices.

In return, ACCS provides the prosecutors with boilerplate administrative forms, letters to check bouncers and operational guidelines, which the prosecutors are free to change but seldom do. ACCS hires instructors for the financial accountability classes, leases classrooms and works with the check-bouncers to schedule attendance and payment.

"The district attorney could hire a bunch of young lawyers and go about the investigation in the way they might in a violent crime," said Jenkins, the ACCS attorney. "The other way to go is for the DAs to say to themselves, âWhat are the elements of this crime?â Then they set up a mechanism where the merchant has to do certain things."

Merchants, who are recruited by ACCS to participate, have to complete a checklist before submitting a bounced check, declaring that it was submitted twice to the bank and that notice was sent to the writer by certified mail. "These folks have utterly ignored repeated pleas to make good," Jenkins said. "Therein lies probable cause. ... The notice makes it abundantly clear â itâs a voluntary program."

Audit: Only a fraction get courtesy notice

But according to interviews and court filings, some participants say they never receive courtesy notices. And plaintiffsâ lawyers say their clients felt intimidated by the threat of steep fines and jail.

"I never heard anything from the bank or from the merchant," Osborn said. "I just got the letter."

"I never heard anything from the bank or from the merchant," Osborn said. "I just got the letter."

Shirley Simeon, an 85-year-old retired psychologist in Chicago, received a repayment notice from ACCS after she bounced a $46 check at Treasure Island Foods, a luxury supermarket. It came under the seal of the Cook County district attorney. Upset, Simeon fired an angry letter back to the grocery chainâs office.

"I have been a customer at the store since 1971," Simeon wrote, "and I am very disappointed to have learned that they would turn such a matter over to an agency of the County."

A 2003 audit of the program in Californiaâs Santa Clara County examined how 120 checks were handled and found that merchants had issued only 39 courtesy notices.

Mom-and-pop merchants fill out a report and send it to ACCS, but because big merchants like Wal-Mart submit bounced checks electronically to ACCS, thereâs no written proof of courtesy notices, Jenkins said. "That does not mean the offender did not receive notice from the merchant,"he said.

Michael OâNeill bounced a $14 check at a drug store in Lee County, Fla., and received a repayment demand letter. An automated message showed up on his voice mail: "Twentieth judicial, stateâs attorney bad check restitution program," it said. "Our office has an official matter requiring your immediate attention."

When he dialed the toll-free number in the letter, OâNeill had no idea he was dealing with a private company. "I believed I was speaking with a government agency," said OâNeill, who now lives in Detroit. "They try to scare you – seriously, is the attorney general of Florida after me for a $14 bounced check?"

OâNeill attempted to repay the merchant directly but was turned away; retailers who sign up with the program agree not to take payment once a check is referred to ACCS. OâNeill refused to pay the more than $200 in fees requested by ACCS. So did Simeon. "I need to tell you that I have no intention of paying $271.49 for an innocent error of $46.49," she wrote in her letter. "I would love to have a âday in court.â "

Osborn was not so defiant. "I called them," she said. "They said basically I had to pay all these costs or, basically, I would be arrested." Osborn handed the money over and attended the class, but she called it "a waste of time."

In Congress, ACCS lobbying drive triumphs

Now, Osborn is a potential plaintiff in the latest round of class-action litigation against ACCS. Plaintiffsâ lawyers in California, Indiana, Florida and Pennsylvania have filed cases in federal court claiming the companyâs practices run counter to state consumer laws and the Fair Debt Collection Practices Act.

The lawsuits accuse ACCS of harassing consumers, misrepresenting themselves as government officials and threatening legal action they donât intend to take. In California, the court has said as many as 900,000 participants may qualify as plaintiffs. In Indiana, the court approved up to 40,000.

The lawsuits persist despite the programâs earlier reprieve from Congress.

As prosecutors touted the benefits, ACCS picked up more contracts through the â90s. Trask promoted the program among DAs in California, and the National District Attorneys Association took note. ACCS made presentations at DA conventions and advertised in The Prosecutor, the national groupâs magazine.

By 2001, ACCS had become "the largest private contractor to District Attorneys in the United States," according to company materials. But consumer advocates and plaintiffsâ lawyers had set their sights on the firm.

"This is one of the most reprehensible collection practices weâve ever seen," said Paul Arons, one of the lead attorneys, who is based in Washington State. "Weâre seeking a court order to stop their illegal practices."

In 2003, with legal fees mounting on several fronts, ACCS hired a lobbying firm, Brownstein Hyatt Farber Schreck, to push for a federal barrier against such lawsuits. The company spent more than $660,000 over the next three years, according to lobbying disclosure reports. The Fair Debt Collection Practices Act had not been changed since 1996, despite pressure by bill collectors to loosen its regulations.

Each year ACCS lobbied Congress for an exemption, consumer advocates objected. "We have the information but not the muscle," said Margot Saunders, legal counsel of the National Consumer Law Center. "DAs have a lot of muscle."

Documents from the class action litigation shed light on the lobbying effort. In one deposition, Mealing testified that Brownstein lobbyists advised him to make campaign contributions to district attorneys with whom the company had contracts, and that he did so.

Former Rep. Mike Oxley, R-Ohio, added the exemption to a draft of the Financial Services Regulatory Relief Act, a wide-ranging bill rewriting rules governing banks and other financial institutions that cleared Congress in the fall of 2006. But in an interview, Frank confirmed that the amendment would not have been included without his support.

Former Rep. Mike Oxley, R-Ohio, added the exemption to a draft of the Financial Services Regulatory Relief Act, a wide-ranging bill rewriting rules governing banks and other financial institutions that cleared Congress in the fall of 2006. But in an interview, Frank confirmed that the amendment would not have been included without his support.

"When you have the national association of district attorneys urging something on their behalf, itâs very hard to resist that," he said. Frank said he was not aware of complaints about the program. "They argued that this was an alternative to people being prosecuted," he said. "I would assume the prosecutor wouldnât send (a repayment letter) to them if they didnât intend to take any action at all."

As Osbornâs case reveals, that is indeed happening. Contracts and budget documents show that some counties set a threshold of $500 or higher for prosecution review; the overwhelming majority bounced checks are for smaller amounts. In Los Angeles County, where the threshold is $500, Kroger supermarket led all retailers with 1,536 bounced checks in December 2008. The average check amount was $89. The average bounced check at Safeway supermarkets was $83 and $64 at CVS drug stores.

"Sound" business takes bankruptcy for cover

In March 2008, lawyers for ACCS asked the judge in Florida to toss out the class action case there on the basis of the exemption. Their argument: Congress only intended "to curb abuses by civil debt collectors (ACCS emphasis). Criminal restitution, however, is not civil debt collection."

But as the judge was set to rule on Jan. 20, ACCS took an unusual step. The day before hearing, the company filed for reorganization under Chapter 11 bankruptcy, effectively halting all four lawsuits.

In a declaration to the court, chief financial officer Michael Wilhelms said ACCS remains "fundamentally sound and healthy." But one of the companyâs backers, Levine Leichtman Capital Partners, a private equity firm, had "expressed its unwillingness to risk an adverse ruling" and threatened to foreclose on the $32 million it loaned to the business. Levine Leichtman did not return a call seeking comment.

With the legal challenges on hold, ACCS faces less pressure to review the way it operates, although Frank said it may be worth looking into the issue of whether the program makes empty threats.

Paul Walsh was the DA in the biggest county in Frankâs congressional district and led the lobbying effort for the exemption while serving as president of the National District Attorneys Association. He defended getting tough with check bouncers to help merchants get paid back.

"Prosecution is coercion," Walsh said. "Thatâs how you get people to do things."

Jenkins said everything ACCS does is under authority of the DAs. "We serve at their pleasure," he said. "American Corrective could not do this on its own."

Contributing: Researcher Lisa Schwartz of ProPublica and Drew Griffin and David Fitzpatrick of CNNâs Special Investigations Unit.