We've updated our popular Gulf Spill FAQ yet again -- adding answers to pressing questions of what the federal government is currently doing to hold BP accountable, what we now know about the spill's size and movement, and what measures the government could potentially take to send a strong message to an oil giant that has a pattern of skirting its own safety rules.

What is the federal government doing to respond to the disaster?

Added June 15

President Barack Obama is scheduled to meet with BP executives this week to discuss damages, an issue for which BP has been criticized for a lack of transparency. The president is also taking to prime-time television today to give a speech about the oil spill.

Although BP says more than 20,000 claims have already been paid, many Gulf businesses continue to report that their claims have gone unpaid or been delayed by red tape.

One potential solution reportedly being considered by the White House is the creation of an independent, third-party panel to handle damage claims and payouts.

Fifty-four senators signed on to a letter calling for BP to set aside $20 billion in an escrow account to pay for damage claims in the Gulf region. Separately, legislation to formally lift the $75 million cap on damages still has not gone through Congress.

What options does the federal government have at its disposal to hold BP accountable?

Added June 15

The Department of Justice has launched both criminal and civil investigations into the BP spill. Attorney General Eric Holder has not specified which companies are under investigation, but the companies connected to the Deepwater Horizon are clear: BP, Transocean and Halliburton. The investigations could potentially result in hundreds of millions in fines for violations of environmental laws. (As we've pointed out, BP could benefit financially from the fact that official flow rate estimates have consistently been proven too low, because civil fines from the Clean Water Act are calculated based on how many barrels of oil have been spilled.)

The Department of Justice has launched both criminal and civil investigations into the BP spill. Attorney General Eric Holder has not specified which companies are under investigation, but the companies connected to the Deepwater Horizon are clear: BP, Transocean and Halliburton. The investigations could potentially result in hundreds of millions in fines for violations of environmental laws. (As we've pointed out, BP could benefit financially from the fact that official flow rate estimates have consistently been proven too low, because civil fines from the Clean Water Act are calculated based on how many barrels of oil have been spilled.)

If company executives are found to have committed fraud or taken part in a coverup, they could face jail time, but experts say this could be a difficult case for the government to make.

The most serious option the federal government has, however, is debarment. As we've reported, the EPA is considering whether to bar BP from receiving government contracts, a move that would cost the company billions and end its drilling in federally controlled oil fields.

What's the latest in stopping the spill?

Updated June 15

By now, BP has attempted eight different methods to stop the spill: Undersea robots to trigger the blowout preventer, the large containment dome, the smaller top hat, a smaller insertion tube, the top kill, the junk shot, the latest containment cap, and two relief wells that are currently being drilled.

None of those methods have plugged the gusher yet. After managing to slice through the riser pipe, BP has a containment cap in place that it says is capturing around 15,000 barrels of oil daily. Given the imprecision of current flow rate estimates--which place the flow rate between 20,000 and 50,000 barrels of oil a day--it's impossible to know what percentage BP is capturing, and the company has been criticized by scientists for claiming to be capturing the "majority" of the gushing oil.

The relief wells remain the best hope for permanently plugging the ruptured well, but they won't be completed until August at the earliest.

Relief wells also have their own risks. The Times-Picayune points out that last fall, engineers drilling a relief well off the coast of Australia lost control of it, resulting in a fire that consumed the original rig.

What is BP doing with the oil it's capturing?

Added June 15

BP announced on June 9 that it would donate the net revenue from the oil it was collecting to help restore wildlife habitats along the Gulf Coast. This announcement came after some began questioning whether it was appropriate for BP to sell its salvaged oil for revenue.

What do we know about the size of the spill and its movement?

Updated June 15

The federal government recently confirmed the existence of giant, undersea plumes of dispersed oil at low concentrations. BP has continued to deny they exist: "It may be down to how you define what a plume is," BP's COO told the "Today" show.

The federal government recently confirmed the existence of giant, undersea plumes of dispersed oil at low concentrations. BP has continued to deny they exist: "It may be down to how you define what a plume is," BP's COO told the "Today" show.

Last week, the government-assembled Flow Rate Technical Group issued another estimate of oil flow that doubled previous estimates. It now estimates that before the well's riser was cut on June 3, anywhere from 20,000 to 50,000 barrels of oil were flowing daily from BP's ruptured well. Given the warnings that cutting the riser pipe would increase the flow, the actual flow rate could still be much larger, and further estimates are under way.

A few scientists from the flow rate group have publicly expressed frustration with BP for not turning over data, not allowing direct measurements, and for overstating how much oil it is capturing.

At the urging of the flow rate team, BP recently began trying to insert a pressure sensor to get direct measurements of the flow of oil, according to The New York Times.

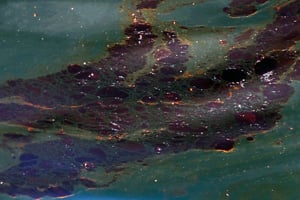

By now, oil has breached barriers and found its way to much of the Gulf coastline. Oil has been found just off the coast of Florida and in some of the state's inland waterways. Scientists predict it will likely travel up the Atlantic Coast in a matter of weeks.

What are the challenges to cleanup and containment?

Added June 15

A major challenge now appears to be the nature of the spill. With so much oil dispersed, Coast Guard Adm. Thad Allen, the national incident commander, has said that there is "no longer a single spill," but "hundreds or thousands of patches of oil" throughout the Gulf.

BP can currently process only 18,000 barrels of oil a day that it's siphoning from the well. The Obama administration has asked the company to put together a plan to increase its collection and processing capacity, and BP has said it will bring in more vessels and equipment to do so, but this won't happen until at least the end of the month.

At the moment, rising temperatures in the Gulf have also slowed cleanup, as workers have to take frequent breaks to avoid heat-related sicknesses.

Are cleanup workers getting sick?

Added June 15

The safety of cleanup workers remains an area of concern, though statistics on health complaints related to chemical exposure remain particularly hard to come by.

BP's data, released June 11, record 485 incidents of worker injury or illness. Of those, 86 were reported as "illnesses," but there were no further statistical breakdowns of the data to show the extent to which chemical exposure may have been a factor.

Statistics from the Louisiana Department of Health and Hospitals, however, report that 51 workers have complained of symptoms believed to be a result of chemical exposure.

BP has maintained that air sampling has turned up no levels of chemical exposure that go beyond federal limits set by the Occupational Safety and Health Association, but experts interviewed by ProPublica said those standards set by OSHA are decades old and may not reflect the latest science, leaving workers exposed to levels "that are perhaps perfectly legal, but not safe." Some air sampling has turned up levels of chemical exposure that exceed limits set by another federal agency, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health, which is a part of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

What's being done to minimize the spill's impacts?

Updated June 15

BP continues to use skimmers and controlled burns to get rid of some of the oil on the surface of the ocean. Those are solutions that have been favored by the Coast Guard in recent days.

Booms are in place to try to protect marshlands and shores, but when one reporter asked the Coast Guard last week about the futility of these devices, Adm. Thad Allen responded that it was a "vexing situation" and that "there is no good solution when oil enters a marshland."

Cleanup workers have continued to slog away, digging at oil-soaked beaches. Reports from the ground like this one from Mother Jones, however, describe other methods of cleaning up the spill, including the use of oil-absorbent pads that cleanup workers referred to as "paper towels."

Corexit dispersant continues to be used both at the surface and below the surface. When asked about its search for a new dispersant, BP has said that it is still working with the EPA to find a better alternative to Corexit, but as Wired points out, no progress has been made in the weeks since the EPA first issued a directive ordering the company to find a less toxic alternative.

What do we know about these dispersants BP is using?

Added May 19

BP has chosen to use two products from a line of dispersants called Corexit, both of which were removed from a list of products approved for use on oil spills in the U.K. Corexit is on the EPA’s list of approved dispersants, but as Greenwire has pointed out, it is more toxic and less effective on south Louisiana crude than other EPA-approved dispersants.

What’s more, the EPA and the Coast Guard are allowing BP to use these dispersants underwater near the ruptured well. They’ve called it a "novel approach" that will ultimately use less dispersant than if the chemicals were applied on the surface. The undersea application, however, is not the recommendedapplication procedure laid out in the EPA’s information on Corexit.

The EPA has acknowledged that dispersants entail "an environmental trade-off," and that their long-term effects on the environment are unknown. It has promised to continue monitoring their use, and EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson said the agency is working with BP to get less toxic dispersants to the site as soon as possible.

Background on the Accident Itself

What are the basics of what happened?

On the night of April 20, the Deepwater Horizon oil rig had an explosion, and two days later, it sank in the Gulf of Mexico. Eleven workers were killed. The rig was operated by British oil giant BP but owned by Transocean, the world’s largest offshore drilling company. The incident ruptured the oil well and has caused what is known as a blowout, or an uncontrollable spill.

What caused it?

Updated May 19

That’s still being investigated. The spill occurred when a safety device called a blowout preventer failed to stop the flow of oil from the well. BP has called the failure of this device "inconceivable," but new details have emerged as to why it may have failed.

According to a "60 Minutes" interview with a survivor, part of the blowout preventer’s seal broke during an accident weeks before the explosion. A Transocean supervisor, when told of the problem, said it was "no big deal," and operations continued despite several such equipment problems.

The rig worker also told "60 Minutes" that BP and Transocean managers had been jostling over who was in charge in the hours before the spill, disagreeing on how to seal the well. One expert told "60 Minutes" that BP’s method—faster, but riskier—may have set the stage for the blowout.

Halliburton was the subcontractor handling the cementing process on the Deepwater Horizon rig, which it completed shortly before the explosion.

Why didn’t the blowout preventer work?

Blowout preventers are hardly foolproof. The Wall Street Journal, which has had great coverage of the disaster, reported that federal regulators had questioned in 2004 whether an "integral" part of blowout preventers, shear rams, would work in deep-water conditions. The Deepwater Horizon rig was drilling in about 5,000 feet of water, and the device obviously did not do the job.

Despite their concerns about the shear rams, regulators from the Minerals Management Service–the agency that regulates offshore drilling—did not issue new regulations to strengthen industry requirements, according to the Journal.

The Journal also reported that another device–one that the BP’s rig lacked–was a backup shutoff device called an acoustic switch that is used by some other oil-producing countries. MMS regulators had once considered requiring the acoustic switch. But after the industry spoke out against it, MMS backed down and simply recommended that the matter be studied.

So the spill wasn’t prevented. Could cleanup and containment efforts have gone better?

Following news of the leak, plans were announced to burn some of the oil in order to contain the spill, but there was no fire boom on hand in order to facilitate that burn, despite a 1994 response plan that suggested their immediate use in the case of a major Gulf oil spill, according to The Press-Register in Mobile, Ala.

Other cleanup and containment efforts include skimming oil off the surface and using miles of protective booms to contain the oil’s movement toward the coast.

BP has also bought up much of the world’s supply of dispersants to use on the spill. Dispersants are chemicals intended to break up the oil. As we’ve reported, those chemicals could present their own environmental concerns, since their exact makeup is kept secret.

Government’s Response—and Its Oversight

What was the White House’s initial response?

Updated May 19

The Obama administration says it has been fully engaged since "day one," but NPR reports that it was only after the rig sank two days after the explosion that the White House stepped up its involvement. At the time, President Barack Obama was assured that no oil was leaking from the ruptured well, and he subsequently left for a short vacation, according to a helpful NPR timeline. A leak was noticed that weekend.

As the weeks went on and the spill continued unabated, the Obama administration grew increasingly frustrated with the oil companies and regulators alike. President Obama blasted oil company executives for blaming each other at congressional hearings, calling it "a ridiculous spectacle," and criticizing the Minerals Management Service for its "cozy relationship" with industry.

What kind of job were regulators doing leading up to this incident?

Updated May 19

We’ve had a hard time getting hold of anyone at the Minerals Management Service, the agency in charge of regulating offshore drilling. Officials there have not responded to our many calls and e-mails.

But in a hearing last week, one MMS official said the agency left it to oil companies to certify that blowout preventers were working properly. The official said the agency "'highly encouraged,’ but did not require," companies to have backup systems to trigger blowout preventers in case of an emergency," according to The Wall Street Journal. That led to this gem of an exchange:

"Highly encourage? How does that translate to enforcement?" Coast Guard Capt. Hung Nguyen, who is co-chairing the investigation, asked at the hearings.

"There is no enforcement," Mr. Saucier replied.

The MMS official also testified that in 2001, new rules were drafted to tighten monitoring of offshore drilling and lay out requirements for blowout preventers, but the rules were never approved by higher-ups in Washington.

The Minerals Management Service—an agency within the Department of the Interior—has a rather mixed record. In 2008, the regulator was involved in a sex and drug scandal with oil and gas company representatives. Since then, the agency has also been criticized for understating the risks of oil spills in its plans to expand drilling off the coast of Alaska. A government investigation also concluded that an office at MMS withheld data on offshore drilling from environmental risk assessors in the agency.

The Washington Post also reported that when BP was seeking permission to drill with the Deepwater Horizon rig, MMS gave BP what is known as a "categorical exclusion"—meaning drilling plans would not be subjected to a detailed environmental analysis. Exemptions are given when the likelihood of a spill is seen to be low. Reuters reports that between 250 and 400 exploration programs in the Gulf have been granted these exclusions. The White House and Department of the Interior have promised to investigate MMS’ liberal use of categorical exclusions.

Interior Secretary Ken Salazar announced several reforms on May 14, including breaking MMS into two separate agencies—one that oversees leasing and collecting royalties and another that oversees safety inspections and enforcement. As we’ve noted, some say this doesn’t go far enough to mitigate the regulator’s conflicts of interest.

Paying for the Disaster

Who’s on the hook for what happened?

Updated May 19

While accepting that it has to pay for the cleanup, BP has tried to distance itself from the spill and push at least some responsibility on Transocean. "It wasn’t our accident," BP CEO Tony Hayward said on NBC’s "Today" show on May 3.

Hayward has said that the company will honor "all legitimate claims for business interruption."

The contractor Transocean, for its part, has tried to limit its liability to $27 million, citing a law that’s a century and a half old, which says a vessel’s owner is liable only for the value of the vessel, according to the AP.

A whole slew of investigations have been launched—and hearings scheduled–by Congressional committees, the Coast Guard and MMS. President Obama also plans to create a commission to investigate the BP spill.

What’s this I hear about a cap on how much BP will have to pay?

Updated May 19

Everyone seems to be in agreement that BP will have to pay for the cleanup. That will include paying back federal agencies for their help in cleanup operations.

But liability for damages is a separate issue, and at the moment, damages are capped at $75 million by a 1990 law. Lawmakers in both the House and the Senate have introduced legislation that would raise the cap on damages to $10 billion. Those lawmakers, with support from the White House, hope to apply the measure retroactively to BP.

At the moment, the measure is having a surprisingly difficult time making it through the Senate, with Republicans blocking the measure. Several Republicans have argued that BP has promised to pay for damages and will "be held to" that promise, and that raising the liability cap to $10 billion could hurt smaller oil companies.