Across the country, states are reexamining their approaches to guardianship, overhauling decades-old laws to better protect vulnerable adults who, because of their age or ailment, can no longer care for themselves.

In Pennsylvania, legislators recently passed a sweeping bill requiring professional guardians to pass a certification exam in order to serve, among other changes. And in Illinois, lawmakers are seeking to make it harder for private guardians to profit off of vulnerable wards who have nobody else to look after them.

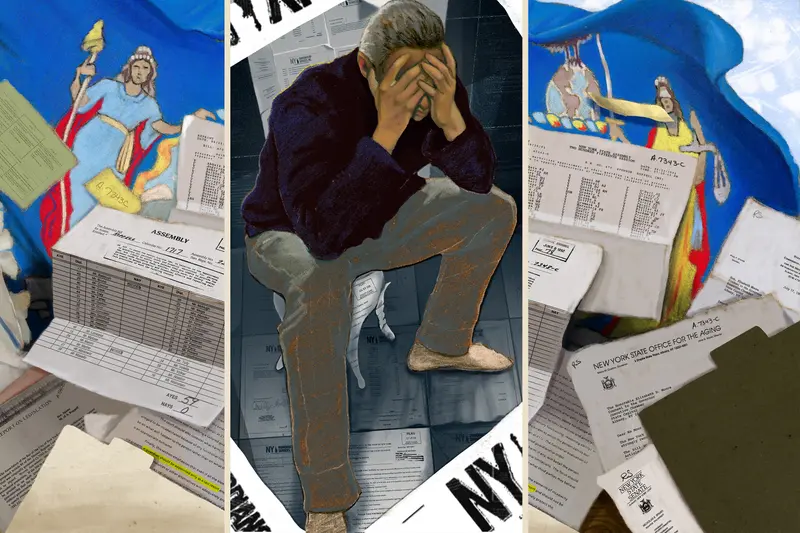

But in New York, where more than 28,000 people rely on guardians to ensure their personal and financial welfare, and where judges, lawyers and advocates have been warning of a growing crisis in the system, elected officials have taken little action.

The $237 billion state budget passed by the Legislature this month includes no new funding to support guardianship services, despite reporting by ProPublica that showed how the state’s system is in shambles, with authorities straining to ensure proper care of elderly and sick wards.

Guardianship Access New York, a coalition of nonprofit providers, had sought a modest sum from legislators: just $5 million to help them manage the finances and health care of poor adults who have nobody else to look after them and little to no money to pay for a private guardian — a group known in the industry as the “unbefriended.” That would have been a significant increase over the $1 million legislators had previously allotted to fund a statewide hotline that hundreds of people have consulted on behalf of friends or family.

But the budget passed April 20 only renewed the $1 million that funds the hotline.

“We’re disappointed that the Legislature is still unwilling to invest in this underfunded mandate that leaves so many people hurting,” said Brianna McKinney, who oversees advocacy for Project Guardianship, a nonprofit that serves as guardian to about 160 New York City wards.

As ProPublica reported last month, there aren’t enough guardians in New York for all of the people judges have found to be in need of one. The system relies on private attorneys, who experts say frequently refuse to take on people who do not have substantial assets, and a small network of nonprofits, two of which have shuttered in recent years because of financial constraints.

Oversight of guardians is also threadbare, ProPublica found. In New York City there are 17,411 people in guardianships but only 157 examiners to scrutinize the reports guardians must file documenting wards’ finances and care, according to state court data. With such thin ranks, reviews can take years to complete, during which time vulnerable wards have been defrauded and neglected.

In recent years, the guardianships of celebrities like Britney Spears and former NFL star Michael Oher have captured the public’s interest and prompted scrutiny of the legal arrangements.

In New York, a recent Lifetime documentary about the former talk show host Wendy Williams — and her guardian’s unsuccessful effort to prevent it from airing — has put an even brighter spotlight on the state’s guardianship system, raising questions of court oversight amid allegations of exploitation and improper care.

Spokespeople for Senate Majority Leader Andrea Stewart-Cousins, Assembly Speaker Carl Heastie and Gov. Kathy Hochul, the state’s most powerful Democrats who negotiated the spending bills, didn’t respond to questions about the lack of guardianship funding in the latest budget or the prospect of future funding.

That includes whether an additional $3 million earmarked for the state’s Office for the Aging’s budget to fund “various aging initiatives” would be used to finance guardianship providers.

Agency spokesperson Roger Noyes said a plan proposed by Hochul to confront the needs of the state’s aging population “presents an opportunity for additional policy focus on guardianship access, programmatic or structural changes, and alternatives to guardianship.” But the governor has provided few specifics on how her proposal will work, particularly with respect to combating elder abuse, a key pillar of the plan.

Many people in guardianship today are elderly and suffer from dementia, Alzheimer’s disease and other ailments that require assistance, according to judges. And advocates say the demand for services will only grow, with the state estimating a population of 5.6 million New Yorkers over 60 by 2030, one of the largest concentrations in the country.

In Illinois, the state’s aging population is driving the guardianship debate. Democratic Rep. Terra Costa Howard, a lawyer, said she was inspired to write legislation after her own representation of an elderly ward. She learned that a private guardianship company and a prominent law firm representing hospitals appeared to be working together, running up costly bills at the ward’s expense.

“What this little piece of legislation has uncovered is a huge problem — elder care is a big, big mess,” Costa Howard told ProPublica. “In our chamber, in our legislature, this is an issue people are willing to fight for. People weren’t paying attention to this until I raised it. I brought it up and now we’re going to go.”

But in New York there is neither a state legislator willing to champion reform nor are there powerful lobbying groups advocating on behalf of those in guardianship, many of whom live in assisted living facilities and nursing homes.

AARP New York said in a statement that it had dedicated its efforts elsewhere this legislative session, including securing funding to support older New Yorkers “who require home- and community-based services” as well as funding an oversight program for nursing homes and adult care facilities.

“If there are additional guardianship proposals introduced in the Legislature, AARP New York will certainly evaluate them in conjunction with our national policy and decide when or if to engage in the issue,” the statement said.

Such legislative action appears unlikely this session, which ends in June.

Sen. Kevin Thomas, a Long Island Democrat who first secured the $1 million to fund the statewide guardianship hotline and advocated for more funding this session, is leaving the Senate when his term ends next year. He didn’t respond to an interview request.