For Missouri public radio reporter Harum Helmy, the Affordable Care Act is more than just a story she covers. It is also a story she’s living.

“I know — an uninsured health reporter,” she wrote to me last month. “The joke’s not lost on me.”

Helmy, 23, a part-time reporter/producer for KBIA in Columbia, Mo., recently completed her coursework at the University of Missouri. She’s on her first professional job. At the station, she covers Obamacare, among other things. But she doesn’t make much money, and if the law worked as it was intended, she would be covered by Missouri’s Medicaid program beginning Jan. 1.

That wasn’t meant to be.

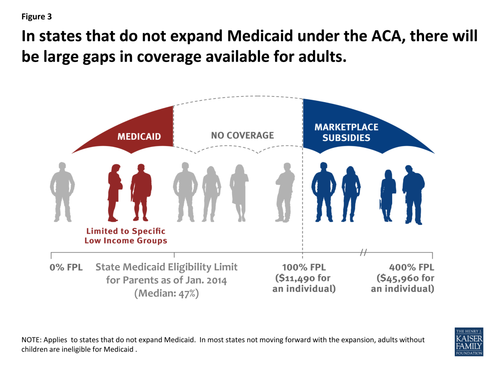

As signed by President Obama, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) would have required every state to expand its Medicaid program for the poor to include adults earning less than 138 percent of the federal poverty level. Those earning more than that, up to four times the poverty level, would qualify for subsidies to purchase health insurance in marketplaces.

But the Supreme Court ruled last year that states could opt out of the Medicaid expansion without consequence, and Missouri along with 24 other states have done just that. The problem is that the law didn’t include subsidies for people in those states who earn less than the federal poverty level to buy coverage through the exchanges — they were supposed to be covered under Medicaid.

That’s the gap in which Helmy sits.

She earns less than the poverty level ($10 an hour for 20 hours per week) and qualifies neither for Medicaid nor a subsidy. Helmy was born in Texas and is a U.S. citizen, though her parents live in Indonesia. While she attended classes at the university, her parents paid for her health coverage.

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, a nonpartisan think tank, “In states that do not expand Medicaid, nearly 5 million poor uninsured adults have incomes above Medicaid eligibility levels but below poverty and may fall into a ‘coverage gap’ of earning too much to qualify for Medicaid but not enough to qualify for Marketplace premium tax credits.” In Missouri, 193,000 people, including Helmy, fall into the gap, Kaiser estimates.

On paper, the Medicaid expansion seems like a great deal. The federal government has agreed to pick up 100 percent of the cost of the expansion for the first three years, phasing down to 90 percent in 2020. But officials in states that have declined to take part view Medicaid as a broken program. They don’t trust the federal government to keep its funding pledge and do not believe they have adequate state funds to cover their portion.

Missouri Gov. Jay Nixon, a Democrat, wants to expand Medicaid in his state, but the Republican-controlled Legislature won’t go along with it.

Helmy discussed her situation in a podcast in October (around the 12-minute mark). “I would just get a little bit personal here and say I’m one of those people,” she said. “I’m in this weird gap where I need insurance, my employer doesn’t give me insurance, but I don’t make enough to get a subsidy.”

I asked her what it felt like to be affected by the act.

“I’m still working out how I feel about being part of the story,” she told me in an email. “I’ve talked about it to potential sources as a way to explain to them why this story is important to me, but I’ve quickly learned that compared to many other Americans in the gap, I’m very privileged, barring any catastrophe. I’m healthy, I have no dependents and barely any debt. I’m overly educated, applying for full-time jobs and looking for additional part-time work in the meantime.”

Helmy said she could get a second job, but it’s difficult because she is still working to complete her master’s thesis. “I know that I’m privileged in the sense that I don’t need to get a second job because I don’t have any debt,” she said in a later phone interview.

Helmy said she’s looking for a full-time job and would consider getting a second job so she can get insurance.

She said that she cares more about the people she covers than about her own situation. “I can see why some anti-ACA people out there think that someone like me wouldn’t need any help,” she said, “I’m outraged that my sources, people in unimaginably worse shape than me, can’t get help.”

Editor’s Note: This post is adapted from Ornstein’s “Healthy buzz” blog. Has your insurance been canceled? Have you tried signing up for coverage through the new exchanges? Help us cover the Affordable Care Act by sharing your insurance story.