California’s labor department says it will conduct an audit of how Travelers Insurance handled the case of paralyzed worker Joel Ramirez, who was left to fend for himself for months after the company withdrew his 24-hour home health care.

Share Your Workers’ Comp Story

As part of our ongoing investigation, we invite you to tell us about your experience navigating the workers’ comp system. Have something we should look into?

Ramirez was featured in a ProPublica/NPR investigation of state changes in workers’ compensation laws nationwide. Since 2003, more than 30 states have cut benefits, created hurdles to getting medical care, or made it more difficult for injured workers to qualify.

The agency said the audit was prompted by our investigation.

The 48-year-old former warehouse manager was hurt in 2009, when a 900-pound crate that had been unsafely stacked at his employer’s Southern California warehouse fell on him. Travelers initially provided him with a home health aide to help him transfer from his wheelchair and with his personal care, as the accident left him incontinent. But the insurer terminated the care after the passage of a new law in 2012 that allowed insurers to subject even old cases to a new, more stringent medical review process.

David Lanier, secretary of the California Labor and Workforce Development Agency, challenged ProPublica and NPR’s description of the new law and said it did not allow insurers to reopen settled cases and renege on previously approved treatment plans. (See full statement.)

Travelers, he said, failed to follow the mandated process and unilaterally terminated Ramirez’s home health care.

‘I Try to Forget’

Paralyzed in a warehouse accident, Joel Ramirez has battled California’s workers’ comp system. View photos.

“Agreed-upon medical treatment must be honored, and California’s 2012 reform law, SB 863, did not change this,” Lanier said. “The insurance company was responsible for Mr. Ramirez’s tragic situation, not the new law.”

In opinions filed last year, however, a workers’ comp judge and the state Workers’ Compensation Appeals Board both wrote that Travelers had used to the new law to justify cutting off Ramirez’s care.

“After the enactment of changes to the law, the defense has asserted that pursuant to Senate Bill 863 that they were no longer bound” by the agreed-upon treatment plan and “were at liberty” to obtain a second opinion and require the new law’s medical review process, Judge Robert Pusey wrote.

Following the ProPublica/NPR report, the labor department’s Division of Workers’ Compensation will audit Travelers’ actions, said Garin Casaleggio, an agency spokesman. If auditors find the company violated the law, it could lead to fines and other penalties.

“We want to be clear that insurers should not use the reforms of SB 863 as a pretext to unilaterally deny agreed-upon care,” Casaleggio said.

Travelers declined to comment. In emailed responses before our reporting on Ramirez’s case was published, Travelers insisted it did not use the new law to withdraw the aide, and only did so after a routine review of his care.

ProPublica and NPR repeatedly sought to interview Lanier over the course of two months before our initial workers’ comp story was published, but the agency did not make him available.

Christine Baker, director of the Department of Industrial Relations, which oversees the state’s workers’ comp system, said in an interview before publication that Ramirez’s case sounded terrible and was not how the system was intended to work. In a written statement, she said workers’ comp was unable to investigate the claims administrator’s handling on the case because it was being litigated.

But by the time of her response in late February, the case involving Travelers had been resolved and was no longer the subject of litigation.

Last week, in a separate case involving Ramirez’s former employer, freight forwarding company Kuehne + Nagel settled charges of “serious and willful misconduct” and agreed to pay additional damages to Ramirez, according to his attorney.

Kuehne + Nagel officials did not return calls and emails.

California’s sweeping 2012 workers’ comp reforms were designed to increase benefits — including some cut deeply by a previous reform — speed up medical treatment decisions, and reduce costs. A coalition of labor and employer groups negotiated the reforms, which had the support of Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown and the legislature, which is dominated by Democrats.

Lanier criticized the story by ProPublica and NPR for not characterizing the 2012 law’s effect fully, noting that it failed to mention that benefits for workers with permanent partial disabilities were increased 30 percent. A graphic published with the story said the 2012 law had “restored some of the wage-loss benefits for workers with permanent partial disabilities” that had been cut under a previous reform law. Lanier said that was not adequate.

According to estimates by the National Council on Compensation Insurance (NCCI), the leading workers’ comp ratings bureau, a 2004 reform law pushed by former Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, reduced benefits for workers with major permanent partial disabilities by 60 percent. So far, NCCI has credited Brown’s law with an 11-percent increase, resulting in a net 50-percent reduction in permanent partial benefits since 2003.

The 2012 law also installed a new medical review process. Under it, all requests for medical treatment — including those involving older injuries — could be reviewed by insurance company doctors and subject to “evidence-based” medical treatment guidelines that are more rigid than considerations applied in the past.

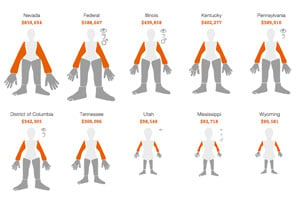

Workers’ Comp Benefits: How Much is a Limb Worth?

Depending on where you work, your compensation for the same injury could be drastically different than in other states. Explore the full interactive.

While insurance company reviews and the guidelines have been around for nearly a decade, medical experts and workers’ comp judges didn’t always follow them. The 2012 law removed judges from the handling of medical disputes and put them in the hands of independent medical reviewers — outside doctors hired by a state contractor who make decisions based on records but never examine injured workers.

The review process only kicks in in disputed cases and most workplace injuries are minor and involve little dispute. Indeed, preliminary data from the California Workers’ Compensation Institute shows that nearly 95 percent of medical care is approved overall.

But in disputed cases, the new independent medical reviewers routinely rule against injured workers’ doctors, denying treatment 91 percent of the time, according to the insurance research institute’s preliminary data.

That shows the new medical review process is “largely correct,” said the institute’s president, Alex Swedlow, and “that 91 percent of the time the decision that is being made either to deny or modify [treatment] was made on solid ground.”

But others see it as a wholesale denial of necessary medical care.

“This case involving Joel Ramirez is not unique,” said Keith More, Ramirez’s attorney. “Every day injured workers around the state of California are being harmed by this law.”

More said insurance companies have been repeatedly using the law to reopen and deny approved care to “hundreds of catastrophically injured workers.”

In an interview in October, one of the architects of the reforms, Angie Wei of the California Labor Federation, said that wasn’t the intent.

“Are insurance companies coming back in and opening up those agreed to, settled lifetime awards and … taking away things that injured workers were guaranteed for life?” she asked. “If they are, that’s wrong and something needs to be done about that.”